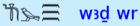

The Ancient Egyptians called the Mediterranean Wadj-wr/Wadj-Wer/Wadj-Ur. This term (lit. 'great green') was the name given by the Ancient Egyptians to the semi-solid, semi-aquatic region characterized by papyrus forests to the north of the cultivated Nile Delta, and, by extension, the sea beyond.[1]

The Ancient Greeks called the Mediterranean simply ἡ θάλασσα (hē thálassa; 'the Sea') or sometimes ἡ μεγάλη θάλασσα (hē megálē thálassa; 'the Great Sea'), ἡ ἡμετέρα θάλασσα (hē hēmetérā thálassa; 'Our Sea'), or ἡ θάλασσα ἡ καθ'ἡμᾶς (hē thálassa hē kath’hēmâs; 'the sea around us').

The Romans called it Mare Magnum ('Great Sea') or Mare Internum ('Internal Sea') and, starting with the Roman Empire, Mare Nostrum ('Our Sea'). The term Mare Mediterrāneum appears later: Solinus apparently used this in the 3rd century, but the earliest extant witness to it is in the 6th century, in Isidore of Seville.[2][3] It means 'in the middle of land, inland' in Latin, a compound of medius ('middle'), terra ('land, earth'), and -āneus ('having the nature of').

The Latin word is a calque of Greek μεσόγειος (mesógeios; 'inland'), from μέσος (mésos, 'in the middle') and γήινος (gḗinos, 'of the earth'), from γῆ (gê, 'land, earth'). The original meaning may have been 'the sea in the middle of the earth', rather than 'the sea enclosed by land'.[4][5]

Ancient Iranians called it the "Roman Sea", in Classic Persian texts was called Daryāy-e Rōm (دریای روم) which may be from Middle Persian form, Zrēh ī Hrōm (𐭦𐭫𐭩𐭤 𐭩 𐭤𐭫𐭥𐭬).[6]

The Carthaginians called it the "Syrian Sea". In ancient Syriac texts, Phoenician epics and in the Hebrew Bible, it was primarily known as the "Great Sea", הים הגדול, HaYam HaGadol, (Numbers; Book of Joshua; Ezekiel) or simply as "The Sea" (1 Kings). However, it has also been called the "Hinder Sea" because of its location on the west coast of the region of Syria or the Holy Land (and therefore behind a person facing the east), which is sometimes translated as "Western Sea". Another name was the "Sea of the Philistines", (Book of Exodus). In Modern Hebrew, it is called הים התיכון HaYam HaTikhon, 'the Middle Sea'.[7] In Classic Persian texts was called Daryāy-e Šām دریای شام) "The Western Sea" or "Syrian Sea".[8]

In Modern Arabic, it is known as al-Baḥr [al-Abyaḍ] al-Mutawassiṭ (البحر [الأبيض] المتوسط) 'the [White] Middle Sea'. In Islamic and older Arabic literature, it was Baḥr al-Rūm(ī) (بحر الروم or بحر الرومي) 'the Sea of the Romans' or 'the Roman Sea'. At first, that name referred to only the Eastern Mediterranean, but it was later extended to the whole Mediterranean. Other Arabic names were Baḥr al-šām(ī) (بحر الشام) ("the Sea of Syria") and Baḥr al-Maghrib (بحرالمغرب) ("the Sea of the West").[9][3]

In Turkish, it is the Akdeniz 'the White Sea'; in Ottoman, ﺁق دكيز, which sometimes means only the Aegean Sea.[10] The origin of the name is not clear, as it is not known in earlier Greek, Byzantine or Islamic sources. It may be to contrast with the Black Sea.[9][7][11] In Persian, the name was translated as Baḥr-i Safīd, which was also used in later Ottoman Turkish. It is probably the origin of the colloquial Greek phrase Άσπρη Θάλασσα, Áspri Thálassa, 'White Sea'.[9]

According to Johann Knobloch, in classical antiquity, cultures in the Levant used colours to refer to the cardinal points: black referred to the north (explaining the name Black Sea), yellow or blue to east, red to south (e.g., the Red Sea), and white to west. This would explain the Greek Áspri Thálassa, the Bulgarian Byalo More, the Turkish Akdeniz, and the Arab nomenclature described above, lit. "White Sea".[12]

References

edit- ^ Golvin, Jean-Claude (1991). L'Égypte restituée, Tome 3. Paris: Éditions Errance. p. 273. ISBN 2-87772-148-5.

- ^ Geoffrey Rickman, "The creation of Mare Nostrum: 300 BC – 500 AD", in David Abulafia, ed., The Mediterranean in History, ISBN 1-60606-057-0, 2011, p. 133.

- ^ a b Vaso Seirinidou, "The Mediterranean" in Diana Mishkova, Balázs Trencsényi, European Regions and Boundaries: A Conceptual History, series European Conceptual History 3, ISBN 1-78533-585-5, 2017, p. 80

- ^ "entry μεσόγαιος". Liddell & Scott. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed, 2001, s.v.

- ^ Dehkhoda, Ali Akbar. ""دریای روم" entry". Parsi Wiki.

- ^ a b Vella, Andrew P. (1985). "Mediterranean Malta" (PDF). Hyphen. 4 (5): 469–472. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017.

- ^ Dehkhoda, Ali Akabar. ""دریای شام" entry". Parsi Wiki.

- ^ a b c Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch., eds. (1960). "Baḥr al-Rūm". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469456.

- ^ Diran Kélékian, Dictionnaire Turc-Français, Constantinople, 1911

- ^ Özhan Öztürk claims that in Old Turkish ak also means "west" and that Akdeniz hence means "West Sea" and that Karadeniz (Black Sea) means "North Sea". Özhan Öztürk. Pontus: Antik Çağ'dan Günümüze Karadeniz'in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi Genesis Yayınları. Ankara. 2011. pp. 5–9. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Johann Knoblock. Sprache und Religion, Vol. 1 (Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1979), 18; cf. Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989). "Black Sea". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/3: Bibliographies II–Bolbol I. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 310–313. ISBN 978-0-71009-126-0.