Naja is a genus of venomous elapid snakes commonly known as cobras (or "true cobras"). Members of the genus Naja are the most widespread and the most widely recognized as "true" cobras. Various species occur in regions throughout Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several other elapid species are also called "cobras", such as the king cobra and the rinkhals, but neither is a true cobra, in that they do not belong to the genus Naja, but instead each belong to monotypic genera Hemachatus (the rinkhals)[1] and Ophiophagus (the king cobra/hamadryad).[2][3]

| Naja | |

|---|---|

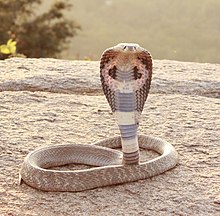

| |

| Indian cobra (Naja naja), species typica of the genus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Naja Laurenti, 1768 |

| Type species | |

| Coluber naja Linnaeus, 1758

| |

Until recently, the genus Naja had 20 to 22 species, but it has undergone several taxonomic revisions in recent years, so sources vary greatly.[4][5] Wide support exists, though, for a 2009 revision[6] that synonymised the genera Boulengerina and Paranaja with Naja. According to that revision, the genus Naja now includes 38 species.[7]

Etymology

editThe origin of this genus name is from the Sanskrit nāga (with a hard "g") meaning "snake". Some[who?] hold that the Sanskrit word is cognate with English "snake", Germanic: *snēk-a-, Proto-IE: *(s)nēg-o-,[8] but Manfred Mayrhofer calls this etymology "not credible", and suggests a more plausible etymology connecting it with Sanskrit nagna, "hairless" or "naked".[9]

Description

editNaja species vary in length and most are relatively slender-bodied snakes. Most species are capable of attaining lengths of 1.84 m (6.0 ft). Maximum lengths for some of the larger species of cobras are around 3.1 m (10 ft), with the forest cobra arguably being the longest species.[10] All have a characteristic ability to raise the front quarters of their bodies off the ground and flatten their necks to appear larger to a potential predator. Fang structure is variable; all species except the Indian cobra (Naja naja) and Caspian cobra (Naja oxiana) have some degree of adaptation to spitting.[11]

Venom

editAll species in the genus Naja are capable of delivering a fatal bite to a human. Most species have strongly neurotoxic venom, which attacks the nervous system, causing paralysis, but many also have cytotoxic features that cause swelling and necrosis, and have a significant anticoagulant effect. Some also have cardiotoxic components to their venom.

Several Naja species, referred to as spitting cobras, have a specialized venom delivery mechanism, in which their front fangs, instead of ejecting venom downward through an elongated discharge orifice (similar to a hypodermic needle), have a shortened, rounded opening in the front surface, which ejects the venom forward, out of the mouth. While typically referred to as "spitting", the action is more like squirting. The range and accuracy with which they can shoot their venom varies from species to species, but it is used primarily as a defense mechanism. The venom has little or no effect on unbroken skin, but if it enters the eyes, it can cause a severe burning sensation and temporary or even permanent blindness if not washed out immediately and thoroughly.

A recent study[12] showed that all three spitting cobra lineages have evolved higher pain-inducing activity through increased phospholipase A2 levels, which potentiate the algesic action of the cytotoxins present in most cobra venoms. The timing of the origin of spitting in African and Asian Naja species corresponds to the separation of the human and chimpanzee evolutionary lineages in Africa and the arrival of Homo erectus in Asia. The authors therefore hypothesise that the arrival of bipedal, tool-using primates may have triggered the evolution of spitting in cobras.

The Caspian cobra (N. oxiana) of Central Asia is the most venomous Naja species. According to a 2019 study by Kazemi-Lomedasht et al, the murine LD50 via intravenous injection (IV) value for Naja oxiana (Iranian specimens) was estimated to be 0.14 mg/kg (0.067-0.21 mg/kg)[13] more potent than the sympatric Pakistani Naja naja karachiensis and Naja naja indusi found in far north and northwest India and adjacent Pakistani border areas (0.22 mg/kg), the Thai Naja kaouthia (0.2 mg/kg), and Naja philippinensis at 0.18 mg/kg (0.11-0.3 mg/kg).[14] Latifi (1984) listed a subcutaneous value of 0.2 mg/kg (0.16-0.47 mg/kg) for N. oxiana.[15] The crude venom of N. oxiana produced the lowest known lethal dose (LCLo) of 0.005 mg/kg, the lowest among all cobra species ever recorded, derived from an individual case of envenomation by intracerebroventricular injection.[16] The Banded water cobra's LD50 was estimated to be 0.17 mg/kg via IV according to Christensen (1968).[17][18] The Philippine cobra (N. philippinensis) has an average murine LD50 of 0.18 mg/kg IV (Tan et al, 2019).[14] Minton (1974) reported 0.14 mg/kg IV for the Philippine cobra.[19][20][21] The Samar cobra (Naja samarensis), another cobra species endemic to the southern islands of the Philippines, is reported to have a LD50 of 0.2 mg/kg,[22] similar in potency to the monocled cobras (Naja kaouthia) found only in Thailand and eastern Cambodia, which also have a LD50 of 0.2 mg/kg. The spectacled cobras that are sympatric with N. oxiana, in Pakistan and far northwest India, also have a high potency of 0.22 mg/kg.[14][23]

Other highly venomous species are the forest cobras and/or water cobras (Boulengerina subgenus). The murine intraperitoneal LD50 of Naja annulata and Naja christyi venoms were 0.143 mg/kg (range of 0.131 mg/kg to 0.156 mg/kg) and 0.120 mg/kg, respectively.[24] Christensen (1968) also listed an IV LD50 of 0.17 mg/kg for N. annulata.[17] The Chinese cobra (N. atra) is also highly venomous. Minton (1974) listed a value of LD50 0.3 mg/kg intravenous (IV),[19] while Lee and Tseng list a value of 0.67 mg/kg subcutaneous injection (SC).[25] The LD50 of the Cape cobra (N. nivea) according to Minton, 1974 was 0.35 mg/kg (IV) and 0.4 mg/kg (SC).[19][26] The Senegalese cobra (N. senegalensis) has a murine LD50 of 0.39 mg/kg (Tan et al, 2021) via IV.[27] The Egyptian cobra (N. haje) of Ugandan locality had an IV LD50 of 0.43 mg/kg (0.35–0.52 mg/kg).[28]

The Naja species are a medically important group of snakes due to the number of bites and fatalities they cause across their geographical range. They range throughout Africa (including some parts of the Sahara where Naja haje can be found), Southwest Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Roughly 30% of bites by some cobra species are dry bites, thus do not cause envenomation (a dry bite is a bite by a venomous snake that does not inject venom).[29] Brown (1973) noted that cobras with a higher rates of 'sham strikes' tend to be more venomous, while those with a less toxic venom tend to envenomate more frequently when attempting to bite. This can vary even between specimens of the same species. This is unlike related elapids, such as those species belonging to Dendroaspis (mambas) and Bungarus (kraits), with mambas tending to almost always envenomate and kraits tending to envenomate more often than they attempt 'sham strikes'.[30]

Many factors influence the differences in cases of fatality among different species within the same genus. Among cobras, the cases of fatal outcome of bites in both treated and untreated victims can be quite large. For example, mortality rates among untreated cases of envenomation by the cobras as a whole group ranges from 6.5–10% for N kaouthia.[30][31] to about 80% for N. oxiana.[32] Mortality rate for Naja atra is between 15 and 20%, 5–10% for N. nigricollis,[33] 50% for N. nivea,[30] 20–25% for N. naja,[34] In cases where victims of cobra bites are medically treated using normal treatment protocol for elapid type envenomation, differences in prognosis depend on the cobra species involved. The vast majority of envenomated patients treated make quick and complete recoveries, while other envenomated patients who receive similar treatment result in fatalities. The most important factors in the difference of mortality rates among victims envenomated by cobras is the severity of the bite and which cobra species caused the envenomation. The Caspian cobra (N. oxiana) and the Philippine cobra (N. philippinensis) are the two cobra species with the most toxic venom based on LD50 studies on mice. Both species cause prominent neurotoxicity and progression of life-threatening symptoms following envenomation. Death has been reported in as little as 30 minutes in cases of envenomation by both species. N. philippinensis purely neurotoxic venom causes prominent neurotoxicity with minimal local tissue damage and pain[35] and patients respond very well to antivenom therapy if treatment is administered rapidly after envenomation. Envenomation caused by N. oxiana is much more complicated. In addition to prominent neurotoxicity, very potent cytotoxic and cardiotoxic components are in this species' venom. Local effects are marked and manifest in all cases of envenomation: severe pain, severe swelling, bruising, blistering, and tissue necrosis. Renal damage and cardiotoxicity are also clinical manifestations of envenomation caused by N. oxiana, though they are rare and secondary.[36] The untreated mortality rate among those envenomed by N. oxiana approaches 80%, the highest among all species within the genus Naja.[32] Antivenom is not as effective for envenomation by this species as it is for other Asian cobras within the same region, like the Indian cobra (N. naja) and due to the dangerous toxicity of this species' venom, massive amounts of antivenom are often required for patients. As a result, a monovalent antivenom serum is being developed by the Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute in Iran. Response to treatment with antivenom is generally poor among patients, so mechanical ventilation and endotracheal intubation is required. As a result, mortality among those treated for N. oxiana envenomation is still relatively high (up to 30%) compared to all other species of cobra (<1%).[15]

Taxonomy

editThe genus contains several species complexes of closely related and often similar-looking species, some of them only recently described or defined. Several recent taxonomic studies have revealed species not included in the current listing in ITIS:[5][37]

- Naja anchietae (Bocage, 1879), Anchieta's cobra, is regarded as a subspecies of N. haje by Mertens (1937) and of N. annulifera by Broadley (1995). It is regarded as a full species by Broadley and Wüster (2004).[38][39]

- Naja arabica Scortecci, 1932, the Arabian cobra, has long been considered a subspecies of N. haje, but was recently raised to the status of species.[40]

- Naja ashei Broadley and Wüster, 2007, Ashe's spitting cobra, is a newly described species found in Africa and also a highly aggressive snake; it can spit a large amount of venom.[41][42]

- Naja nigricincta Bogert, 1940, was long regarded as a subspecies of N. nigricollis, but was recently found to be a full species (with N. n. woodi as a subspecies).[43][44]

- Naja senegalensis Trape et al., 2009, is a new species encompassing what were previously considered to be the West African savanna populations of N. haje.[40]

- Naja peroescobari Ceríaco et al. 2017, is a new species encompassing what was previously considered the São Tomé population of N. melanoleuca.[45]

- Naja guineensis Broadley et al., 2018, is a new species encompassing what were previously considered to be the West African forest populations of N. melanoleuca.[7]

- Naja savannula Broadley et al., 2018, is a new species encompassing what were previously considered to be the West African savanna populations of N. melanoleuca.[7]

- Naja subfulva Laurent, 1955, previously regarded as a subspecies of N. melanoleuca, was recently recognized as a full species.[7]

Two recent molecular phylogenetic studies have also supported the incorporation of the species previously assigned to the genera Boulengerina and Paranaja into Naja, as both are closely related to the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca).[43][46] In the most comprehensive phylogenetic study to date, 5 putative new species were initially identified, of which 3 have since been named.[4]

The controversial amateur herpetologist Raymond Hoser proposed the genus Spracklandus for the African spitting cobras.[47] Wallach et al. suggested that this name was not published according to the Code and suggested instead the recognition of four subgenera within Naja: Naja for the Asiatic cobras, Boulengerina for the African forest, water and burrowing cobras, Uraeus for the Egyptian and Cape cobra group and Afronaja for the African spitting cobras.[6] International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature issued an opinion that it "finds no basis under the provisions of the Code for regarding the name Spracklandus as unavailable".[48]

Asiatic cobras are believed to further be split into two groups of southeastern Asian cobras (N. siamensis, N. sumatrana, N. philippinensis, N. samarensis, N. sputatrix, and N. mandalayensis) and western and northern Asian cobras (N. oxiana, N. kaouthia, N. sagittifera, and N. atra) with Naja naja serving as a basal lineage to all species.[49]

Species

edit| Image[5] | Species[5] | Authority[5] | Subsp.*[5] | Common name | Geographic range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. anchietae | Bocage, 1879 | 0 | Anchieta's cobra (Angolan Cobra) | Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, eastern Zimbabwe | |

| N. annulata | (Buchholz and Peters, 1876) | 1 | Banded water cobra | Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire), the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Rwanda, and the province of Cabinda in Angola | |

| N. annulifera | Peters, 1854 | 0 | Snouted cobra | Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe | |

| †N. antiqua | Rage, 1976 | 0 | Miocene-aged strata of Morocco | ||

| N. arabica | Scortecci, 1932 | 0 | Arabian cobra | Oman, Saudi Arabia, Yemen | |

| N. ashei | Wüster and Broadley, 2007 | 0 | Ashe's spitting cobra (giant spitting cobra) | southern Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, eastern Uganda | |

| N. atra | Cantor, 1842 | 0 | Chinese cobra | southern China, northern Laos, Taiwan, northern Vietnam | |

| N. christyi | (Boulenger, 1904) | 0 | Congo water cobra | the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire), the Republic of Congo, and the province of Cabinda in Angola | |

| N. fuxi |

Shi, Vogel, Chen, & Ding, 2022 |

0 | Brown banded cobra | China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam | |

| N. guineensis | Broadley, Trape, Chirio, Ineich &Wüster, 2018 | 0 | Black forest cobra | Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Togo | |

| N. haje | Linnaeus, 1758 | 0 | Egyptian cobra | Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda, South Sudan, Sudan, Cameroon, Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt | |

| †N. iberica | Szyndlar, 1985 | Miocene-aged strata of Spain | |||

| N. kaouthia | Lesson, 1831 | 0 | Monocled cobra | Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia, southern China, eastern India, Laos, northwestern Malaysia, Nepal, Thailand, southeastern Tibet, Vietnam | |

| N. katiensis | Angel, 1922 | 0 | Mali cobra (Katian spitting cobra) | Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Mali, Gambia, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo | |

| N. mandalayensis | Slowinski & Wüster, 2000 | 0 | Mandalay spitting cobra (Burmese spitting cobra) | Myanmar (Burma) | |

| N. melanoleuca | Hallowell, 1857 | 0 | Central African forest cobra | Angola, Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire), Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria | |

| N. mossambica | Peters, 1854 | 0 | Mozambique spitting cobra | extreme southeastern Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia, northeastern Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania (including Pemba Island), Zambia, Zimbabwe | |

| N. multifasciata | Werner, 1902 | 0 | Many-banded cobra | Cameroon, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire), Gabon | |

| N. naja | (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | Indian cobra (spectacled cobra) | Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | |

| N. nana | Collet & Trape, 2020 | 0 | Dwarf water cobra | Democratic Republic of Congo | |

| N. nigricincta | Bogert, 1940 | 1 | Zebra spitting cobra | Angola, Namibia, South Africa | |

| N. nigricollis | Reinhardt, 1843 | 0 | Black-necked spitting cobra | Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire) (except in the central region), Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Somalia, Togo, Uganda, Zambia | |

| N. nivea | (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | Cape cobra (yellow cobra) | Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa | |

| N. nubiae | Wüster & Broadley, 2003 | 0 | Nubian spitting cobra | Chad, Egypt, Eritrea, Niger, Sudan | |

| N. obscura | Saleh & Trape, 2023 | 0 | Obscure cobra | Egypt | |

| N. oxiana | (Eichwald, 1831) | 0 | Caspian cobra | Afghanistan, northwestern India, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan | |

| N. pallida | Boulenger, 1896 | 0 | Red spitting cobra | Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania | |

| N. peroescobari | Ceríaco, Marques, Schmitz & Bauer, 2017 | 0 | São Tomé forest cobra, cobra preta | São Tomé and Príncipe (São Tomé) | |

| N. philippinensis | Taylor, 1922 | 0 | Philippine cobra | the Philippines (Luzon, Mindoro) | |

| †N. romani | (Hofstetter, 1939) | 0 | † | Miocene-aged strata of France, Germany, Austria, Russia, Hungary, Greece and Ukraine.[50] | |

| N. sagittifera | Wall, 1913 | 0 | Andaman cobra | India (the Andaman Islands) | |

| N. samarensis | Peters, 1861 | 0 | Samar cobra | the Philippines (Mindanao, Bohol, Leyte, Samar, Camiguin) | |

| N. savannula | Broadley, Trape, Chirio & Wüster, 2018 | 0 | West African banded cobra | Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo | |

| N. senegalensis | Trape, Chirio & Wüster, 2009 | 0 | Senegalese cobra | Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal | |

| N. siamensis | Laurenti, 1768 | 0 | Indochinese spitting cobra | Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam | |

| N. sputatrix | F. Boie, 1827 | 0 | Javan spitting cobra | Indonesia (Java, the Lesser Sunda Islands, East Timor) | |

| N. subfulva | Laurent, 1955 | 0 | Brown forest cobra | Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire), Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | |

| N. sumatrana | Müller, 1887 | 0 | Equatorial spitting cobra | Brunei, Indonesia (Sumatra, Borneo, Bangka, Belitung), Malaysia, the Philippines (Palawan), southern Thailand, Singapore |

- Not including the nominate subspecies

† Extinct

T Type species[2]

References

edit- ^ Spawls, S; Branch, B (1995). The Dangerous Snakes of Africa (1st. ed.). Ralph Curtis Books. ISBN 9780883590294. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b Zhao, E; Adler, K (1993). Herpetology of China (1st ed.). Society for the Study of Amphibians & Reptiles. p. 522. ISBN 9780916984281. OCLC 716490697. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Vogel, G (31 March 2006). Terralog: Venomous Snakes of Asia, Vol. 14 (1 ed.). Frankfurt Am Main: Hollywood Import & Export. p. 148. ISBN 978-3936027938. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b von Plettenberg Laing, Anthony (2018). "A multilocus phylogeny of the cobra clade elapids". MSC Thesis.

- ^ a b c d e f "Naja". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ a b Wallach, Van; Wüster, W; Broadley, Donald G. (2009). "In praise of subgenera: taxonomic status of cobras of the genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2236 (1): 26–36. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2236.1.2. S2CID 14702999.

- ^ a b c d Wüster, W; et al. (2018). "Integration of nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences and morphology reveals unexpected diversity in the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca) species complex in Central and West Africa (Serpentes: Elapidae)". Zootaxa. 4455 (1): 68–98. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4455.1.3. PMID 30314221.

- ^ "Proto-IE: *(s)nēg-o-, Meaning: snake, Old Indian: nāgá- m. 'snake', Germanic: *snēk-a- m., *snak-an- m., *snak-ō f.; *snak-a- vb". Starling.rinet.ru.

- ^ Mayrhofer, Manfred (1996). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter. p. II.33. ISBN 978-3-8253-4550-1.

- ^ "Naja melanoleuca - General Details, Taxonomy and Biology, Venom, Clinical Effects, Treatment, First Aid, Antivenoms". WCH Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Queensland. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Wüster, W; Thorpe, RS (1992b). "Dentitional phenomena in cobras revisited: fang structure and spitting in the Asiatic species of Naja (Serpentes: Elapidae)". Herpetologica. 48: 424–434. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Kazandjian, TD (January 2021). "Convergent evolution of pain-inducing defensive venom components in spitting cobras" (PDF). Science. 371 (6527): 386–390. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..386K. doi:10.1126/science.abb9303. PMC 7610493. PMID 1294479. S2CID 231666401.

- ^ Kazemi-Lomedasht, F; Yamabhai, M; Sabatier, J; Behdani, M; Zareinejad, MR; Shahbazzadeh, D (5 December 2019). "Development of a human scFv antibody targeting the lethal Iranian cobra (Naja oxiana) snake venom". Toxicon. 171: 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.10.006. PMID 31622638. S2CID 204772656. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Wong, KY; Tan, CH; Tan, NH (3 January 2019). "Venom and Purified Toxins of the Spectacled Cobra (Naja naja) from Pakistan: Insights into Toxicity and Antivenom Neutralization". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 94 (6): 1392–1399. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0871. PMC 4889763. PMID 27022154.

- ^ a b Latifi, Mahmoud (1984). Snakes of Iran. Society for the Study of Amphibians & Reptiles. ISBN 978-0-916984-22-9.

- ^ Khare, AD; Khole V; Gade PR (December 1992). "Toxicities, LD50 prediction and in vivo neutralisation of some elapid and viperid venoms". Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 30 (12): 1158–62. PMID 1294479.

- ^ a b Christensen, PA (1968). Chapter 16 - The Venoms of Central and South African Snakes. Academic Press. pp. 437–461. ISBN 978-1-4832-2949-2. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Boulengerina annulata - General Details, Taxonomy and Biology, Venom, Clinical Effects, Treatment, First Aid, Antivenoms". Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Minton, SA (1974). Venom Diseases. University of Michigan: Thomas. ISBN 0398030510.

- ^ Watt, G; Theakston RD; Hayes CG; Yambao ML; Sangalang R; et al. (4 December 1986). "Positive response to edrophonium in patients with neurotoxic envenoming by cobras (Naja naja philippinensis). A placebo-controlled study". New England Journal of Medicine. 315 (23): 1444–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198612043152303. PMID 3537783.

- ^ Hauert, Jacques; ichel Maire; Alexandre Sussmann; Dr. J. Pierre Bargetz (July 1974). "The major lethal neurotoxin of the venom of Naja naja phillippinensis: Purification, physical and chemical properties, partial amino acid sequence". International Journal of Peptide and Protein Research. 6 (4): 201–222. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3011.1974.tb02380.x. PMID 4426734.

- ^ Palasuberniam, Praneetha; Chan, Yi Wei; Tan, Kae Yi; Tan, Choo Hock (2021). "Snake Venom Proteomics of Samar Cobra (Naja samarensis) from the Southern Philippines: Short Alpha-Neurotoxins as the Dominant Lethal Component Weakly Cross-Neutralized by the Philippine Cobra Antivenom". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12: 3641. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.727756. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC 8740184. PMID 35002690.

- ^ Lysz, Thomas W.; Rosenberg, Philip (May 1974). "Convulsant activity of Naja naja oxiana venom and its phospholipase A component". Toxicon. 12 (3): 253–265. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(74)90067-1. PMID 4458108.

- ^ Weinstein, SA; Schmidt, JJ; Smith, LA (1991). "Lethal toxins and cross neutralization of venoms from the African Water Cobras, Boulengerina annulata annulata and Boulengerina christyi". Toxicon. 29 (11): 1315–27. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(91)90118-b. PMID 1814007. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Lee, CY; Tseng, LF (September 1969). "Species differences in susceptibility to elapid venoms". Toxicon. 7 (2): 89–93. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(69)90069-5. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 5823351. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Minton, SA (1996). Par'Book. Washington D.C., US: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-648-5.

- ^ Wong, KY; Tan, KY; Tan, NH; Tan, CH (2021). "A Neurotoxic Snake Venom without A2: Proteomics and Cross-Neutralization of the Venom from Senegalese Cobra, Naja senegalensis (Subgenus: Uraeus)". Toxins. 13 (1): 60. doi:10.3390/toxins13010060. PMC 7828783. PMID 33466660.

- ^ Harrison, GO; Oluoch, RA; Ainsworth, S; Alsolaiss, J; Bolton, F; Arias, AS; et, al (2017). "The murine venom lethal dose (LD50) of the East African snakes". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005969.t003. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Naik, BS (2017). ""Dry bite" in venomous snakes: A review" (PDF). Toxicon. 133: 63–67. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.04.015. PMID 28456535. S2CID 36838996. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Brown, John H. (1973). Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, IL US: Charles C. Thomas. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-398-02808-4.

- ^ Warrell, DA (22 August 1995). "Clinical Toxicology of Snakebite in Asia". Handbook of: Clinical Toxicology of Animal Venoms and Poisons (1st ed.). CRC Press. pp. 493–594. doi:10.1201/9780203719442-27. ISBN 9780203719442. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b Gopalkrishnakone, Chou, P., LM (1990). Snakes of Medical Importance (Asia-Pacific Region). Singapore: National University of Singapore. ISBN 978-9971-62-217-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ Warrell, David A. "Snake bite" (PDF). Seminar. Lancet 2010 (volume 375, issue 1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Norris MD, Robert L.; Minton, Sherman A. (10 September 2013). "Cobra Envenomation". Medscape. United States. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Watt, G.; Padre L; Tuazon L; Theakston RD; Laughlin L. (September 1988). "Bites by the Philippine cobra (Naja naja philippinensis): prominent neurotoxicity with minimal local signs". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 39 (3): 306–11. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.306. PMID 3177741.

- ^ "Naja oxiana". Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Kazemi, Elmira; Nazarizadeh, Masoud; Fatemizadeh, Faezeh; Khani, Ali; Kaboli, Mohammad (2021). "The phylogeny, phylogeography, and diversification history of the westernmost Asian cobra (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja oxiana) in the Trans-Caspian region". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (5): 2024–2039. doi:10.1002/ece3.7144. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 7920780. PMID 33717439.

- ^ Broadley, D.G.; Wüster, W. (2004). "A review of the southern African 'non-spitting' cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja)". African Journal of Herpetology. 53 (2): 101–122. doi:10.1080/21564574.2004.9635504. S2CID 84853318.

- ^ Naja anchietae at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 13 April 2007.

- ^ a b Trape, J.-F.; Chirio, L.; Broadley, D.G.; Wüster, W. (2009). "Phylogeography and systematic revision of the Egyptian cobra (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja haje) species complex, with the description of a new species from West Africa". Zootaxa. 2236: 1–25. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2236.1.1.

- ^ Wüster, W.; Broadley, D.G. (2007). "Get an eyeful of this: a new species of giant spitting cobra from eastern and north-eastern Africa (Squamata: Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja)". Zootaxa. 1532: 51–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1532.1.4.

- ^ Naja ashei at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 13 April 2007.

- ^ a b Wüster, W.; Crookes, S.; Ineich, I.; Mane, Y.; Pook, C.E.; Trape, J.-F.; Broadley, D.G. (2007). "The phylogeny of cobras inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences: evolution of venom spitting and the phylogeography of the African spitting cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja nigricollis complex)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (2): 437–453. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.07.021. PMID 17870616.

- ^ Naja nigricincta at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 29 December 2008.

- ^ Ceríaco, L; et al. (2017). "The "Cobra-preta" of São Tomé Island, Gulf of Guinea, is a new species of Naja Laurenti, 1768 (Squamata: Elapidae)". Zootaxa. 4324 (1): 121–141. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4324.1.7.

- ^ Nagy, Z.T., Vidal, N., Vences, M., Branch, W.R., Pauwels, O.S.G., Wink, M., Joger, U., 2005. Molecular systematics of African Colubroidea (Squamata: Serpentes). In: Huber, B.A., Sinclair, B.J., Lampe, K.-H. (Eds.), African Biodiversity: Molecules, Organisms, Ecosystems. Museum Koenig, Bonn, pp. 221–228.

- ^ Hoser, R., 2009. Naja, Boulengerina and Paranaja. Australasian Journal of Herpetology, 7, pp.1-15.

- ^ "Opinion 2468 (Case 3601) – Spracklandus Hoser, 2009 (Reptilia, Serpentes, Elapidae) and Australasian Journal of Herpetology issues 1–24: confirmation of availability declined; Appendix A (Code of Ethics): not adopted as a formal criterion for ruling on Cases". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 78 (1): 42–45. 2021. doi:10.21805/bzn.v78.a012. ISSN 0007-5167. S2CID 233448875.

- ^ Kazemi, Elmira; Nazarizadeh, Masoud; Fatemizadeh, Faezeh; Khani, Ali; Kaboli, Mohammad (2020-08-18). "Phylogeny, phylogeography and diversification history of the westernmost Asian cobra (Naja oxiana) in the Trans-Caspian region". doi:10.22541/au.159774318.89992224. S2CID 225411032. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Syromyatnikova, E.; Tesakov, A.; Titov, V. (2021). "Naja romani (Hoffstetter, 1939)(Serpentes: Elapidae) from the late Miocene of the Northern Caucasus: the last East European large cobra". Geodiversitas. 43 (19): 683–689. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a19. S2CID 238231298.

External links

edit- Naja at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 13 April 2007.