This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. In particular, the article covers both a village and river in the intro, needs focus on either the village or river for the article focus. (December 2020) |

It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled Mullins River (river) and Mullins River (village). (discuss) (September 2023) |

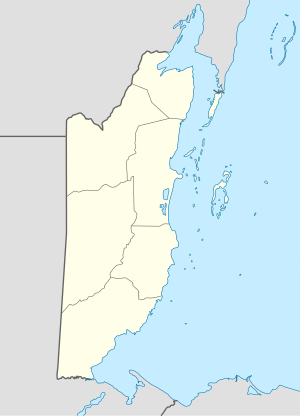

Mullins River is the name of both a river and of a village on that river in the Stann Creek District of Belize.

Mullins River | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 17°06′N 88°18′W / 17.100°N 88.300°W | |

| Country | |

| District | Stann Creek District |

| Constituency | Stann Creek West |

| Population (2000) | |

• Total | 198 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central) |

| Climate | Af |

The village of Mullins River is located at the mouth of the river of the same name on the coast of the Caribbean Sea, north of Dangriga. At the time of the 1904 census, Mullins River had a population of 243 people, but by 2000, the population had dwindled to 198.

Religious history

editMullins River was the locus of early missionary activity in 19th century Belize. Some Omoa residents from Spanish Honduras had settled there after the accession of the liberal Morazán to power in Honduras in 1830[1] In 1832, Fray Antonio began to work among them, building “a small Catholic chapel that was served intermittently by a Catholic priest.” This was the first Catholic chapel in Belize in modern times.[2][3] In 1836, Fray Rubio from Bacalar replaced Fray Antonio.

During 1830, Baptist minister James Bourne began visiting Mullins River and Stann Creek. He reported the population of each of the communities as about 100.[2] By 1832, the number had grown to 500. In November 1834, Methodists Thomas Jefferies and John Greenwood had arrived in Mullins River, and by 1836, had a chapel and school.

In the mid-1800s, Mullins River was a village of Creole and Spanish people. The Creoles resided in Belize Town and maintained small plantations at Mullins River, which they visited occasionally. The Spanish tended to move between Mullins River itself and Spanish Town, a nearby settlement of immigrants.[4]

In 1840, Apolonia Mejia brought to Mullins River from the Shrine of Nuestro Señor de Esquipulas in southern Guatemala the image of the crucified black Christ. The image was exposed in church for festivities during her life and donated to the church after her death, becoming “an object of public veneration ever since. Pilgrimages have been started from various points of the colony to visit the sacred image.”[1]

The report of Bishop Di Pietro’s visit in 1894 gave the number of Catholics as 243 and the average attendance of children at the school as 48. The school was going on satisfactorily because “the retail liquor license has been stopped, [so] the morality of the place has improved. Formerly Mullins River had a bad reputation but now the people spend their money on improving their plantations instead of wasting it in the liquor shop”[1] The hurricane of 1941 destroyed the 1832 Mullins River Catholic church, which was rebuilt in 1942.

The town

editBy the late 1880s, the Belize Independent noted the addition to Mullins River of a few White settlers, with a few Caribs (Garifuna) working up the river at different banks. But in the town itself there were “few or no Carib residents.” The article further described Mullins River as a town with roadways and town operations, with the district magistrate holding court once monthly, and two policemen stationed there. The large Wesleyan population was building a “fine new church and schoolroom.”[5]

Mullins River hosted British Honduras Fruit Company and Belize Fruit Company, the former having been Drake’s Sugar Estate. Further economic activity included private farms of bananas, coconuts, and cacao. Mullins River, navigable by dory for some 25 miles, afforded “a natural highway to the virgin lands at the back as well as for sending down the produce.”[6] The town served also as a playground for many Belize City folk during the vacation months of March through May.”

References

edit- ^ a b c Bishop di Pietro, The Angelus, September 1894. Accessed at archives Roman Catholic Diocese of Belize City-Belmopan.

- ^ a b Johnson, W.R. (1985). A history of Christianity in Belize: 1776-1838. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. p. 181.

- ^ Sutti, H.J. (n.d.). A History of the Chief Events in the mission of British Honduras. St. Louis: Midwest Jesuit Archives.

- ^ Woods, Charles M. Sr.; et al. (2015). Years of Grace: The History of Roman Catholic Evangelization in Belize: 1524-2014. Belize City: Roman Catholic Diocese of Belize City-Belmopan. p. 59.

- ^ "Mullins River". Belize Independent. Belize Archives and Records Service. Belmopan: 8. October 11, 1888.

- ^ Morris, D. (1883). The colony of British Honduras: Its resources and prospects. Charing Cross, London: Edward Stanford. pp. 25f.