Mount Olivet Cemetery is a historic cemetery in Fort Worth, Texas. With its first burial in 1907, Mount Olivet is the first perpetual care cemetery in the South. Its 130-acre site is located northeast of downtown Fort Worth at the intersection of North Sylvania Avenue and 28th Street adjacent to the Oakhurst Historic District. Over 70,000 people are buried at Mount Olivet, including Fort Worth settlers and members of many prominent local families.

| Mount Olivet Cemetery | |

|---|---|

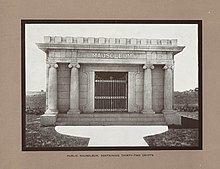

Entrance to Mount Olivet, ca. 1912–1917 | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1907 |

| Location | Fort Worth, Texas |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 32°47′31″N 97°18′50″W / 32.792°N 97.314°W |

| Owned by | Mount Olivet Cemetery Association |

| Size | 130 acres |

| Website | https://www.greenwoodfuneralhomes.com |

| Find a Grave | Mount Olivet Cemetery |

History

editModeled after Mount Olivet Cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee, Fort Worth's Mount Olivet was established by Flavious McPeak (1858–1933) and his wife, Johnnie Clara Lester McPeak (1858–1936), on the former Charles B. Daggett homestead. The McPeaks, Tennessee natives, came to Fort Worth in 1894. Mrs. McPeak purchased the Daggett land, originally developed by cereal magnate C.W. Post and known locally as "Oak Hill," the following year. The McPeaks lived in a two-story home on the property until the cemetery opened in 1907.[1][2] Businessman Flavious McPeak served as director of the Wireless Telegraph Company, the Western National Bank, and vice president of the Fort Worth Iron and Steel Manufacturing Company.[2][3]

The first burial, that of Thomas Hill, took place on April 9, 1907, before the official dedication of the cemetery[4][5] (a Texas Historical Marker placed at the cemetery in 1986 erroneously lists a burial on April 11 as the first).[6] The cemetery officially opened on May 1, 1907 with no sod and few plantings as the area was suffering a severe drought. R.O. Phillips, former superintendent of Pioneers Rest cemetery, was hired to manage the site and the cemetery's offices were housed in the Western National Bank building in downtown Fort Worth. Mount Olivet was the first cemetery in the southern United States to offer perpetual care; 25% of the cost of each burial plot went into a reserve fund, whose interest paid for ongoing maintenance of the property.[7][8] Trustees of the reserve fund included representatives of the mayor's office, the 48th district court, and the office of the Tarrant County judge.[9] The Mount Olivet Company was incorporated on June 6, 1908 with Flavious McPeak as president; former mayor B. B. Paddock was also a trustee.[2]

The cemetery was advertised daily in the Fort Worth Telegram newspaper throughout 1907 and 1908. In 1908, a new road connecting Fort Worth and then-suburb Riverside was built, making the cemetery far more accessible to local residents.[10] In 1909, a receiving vault with 32 crypts was constructed to facilitate burials and prevent grave-robbing. The $8,000 construction cost forced McPeak to default on loans, and he foreclosed in 1912. The directors of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank of Fort Worth paid off McPeak's debt and assumed ownership.[11][12] To further promote the cemetery and its parklike setting, the Mount Olivet Cemetery Association established bus service from downtown Fort Worth in 1914. The "auto passenger bus" ran six times a day between the cemetery and the Flatiron Building.[13] Local businessman William J. Bailey acquired Mount Olivet in 1917, and his son, John, became its general manager in 1945. In 1956, the Baileys converted the Mount Olivet company into a nonprofit organization. The original cemetery's articles of incorporation stating that "no negro or person of African descent shall ever be interred on said lots" were found to be illegal and were amended in 1969. Though it had been restored in the 1940s, the receiving vault was determined to be beyond repair and demolished in 1983.[2]

In 1986, Mount Olivet was recognized with a Texas Historical Marker in honor of the Texas Sesquicentennial.[1] Mount Olivet and nearby Greenwood Memorial Park are owned by the Bailey family under the auspices of the Mount Olivet Cemetery Association.[14][15]

Notable graves and monuments

editLike many historic cemeteries, sections of Mount Olivet are dedicated to specific religious denominations and other groups, such as the International Typographic Union section.[16] In 1918, the cemetery became the resting place of nearly 600 victims of the flu pandemic.[1] In 1929, an agreement between the Mount Olivet and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dallas designated an official Catholic burial section. Upon the burials of the McPeaks in the 1930s, a section was designated the Founders' Lawn.[2] Notable individuals interred at Mount Olivet include:[17]

- Stephen Bruton (1948–2009) – musician, actor

- Tim Cole (1960–1999) – victim of miscarriage of justice

- Effie Juanita "Anna" Carter Davis (1917–2004) – gospel singer and wife of Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis

- Sherrill Headrick (1937–2008) – NFL football player

- James A. Hovencamp (d. 1915) – Tarrant County settler and cattle rancher

- Mary Daggett Lake (1880–1955) – Botanist, educator, and Texas historian

- Robert David Law (1944–1969) – Vietnam War veteran and recipient of the Medal of Honor

- Samuel S. Losh (1884–1943) – composer, vocalist, and music educator

- William Pinckney McLean (1836–1925) – Member of the Constitutional Convention of 1875, the first Texas Railroad Commission, and the United States House of Representatives

- Flavious McPeak (1858–1933) and Johnnie McPeak (1858–1936) – founders of Mount Olivet Cemetery

- Helen Matusevich Oujesky (1930–2010) – professor of microbiology

- Harley Sewell (1931–2011) – NFL football player

- S. D. Shannon (d. 1946) – North Fort Worth alderman and founder of Shannon Funeral Home

- Lee Shepherd (1944–1985) – drag racing driver

- Catherine Moylan Singleton (1904–1969) – Ziegfeld Follies actress and 1926 Miss Universe

- Ron Wright (1953–2021) – US congressman for Texas's 6th district (2019–2021)

References

edit- ^ a b c "Mount Olivet Cemetery Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e McPeak, Howard H. (1987). A collection of information about the Flavious G. and Johnnie Clara McPeak family, 1894–1936 : and their descendants : with documents and pictures. OCLC 21963894.

- ^ "F.G. McPeak Donated Homestead for Historic Cemetery". Fort Worth News-Tribune. 1987-10-02.

- ^ "First – burial in Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Fort Worth TX – First of its Kind on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "Necrological". Fort Worth Record and Register. 1907-04-10.

- ^ "Mount Olivet Cemetery". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "Mount Olivet Opened". Fort Worth Telegram. 1907-04-07.

- ^ "Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Fort Worth". www.fortworthtexasarchives.org. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "[Mount Olivet Cemetery advertisement]". Fort Worth Telegram. 1907-04-28.

- ^ "New Road Opened". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 1908-01-05.

- ^ "The (Burial) Plot Thickens: Bailey's Bluff | Hometown by Handlebar". hometownbyhandlebar.com. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "[First National Bank vs Mount Olivet Cemetery announcement]". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 1912-11-15.

- ^ "Cemetery Bus Will Accept Passengers". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 1914-08-15.

- ^ "For Generations to Come" (PDF). greenwoodfuneralhomes.com. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "Visitor Guide". Greenwood Funeral Home. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ "American Worker, Put Away Your Seersucker". hometownbyhandlebar.com. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (3rd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786479924.