Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola GCFR, also known as M. K. O. Abiola (// ⓘ; 24 August 1937 – 7 July 1998) was a Nigerian business magnate, publisher, and politician. He was the honorary supreme military commander of the Oyo Empire[a] and an aristocrat of the Egba clan.[6][7]

Moshood Abiola | |

|---|---|

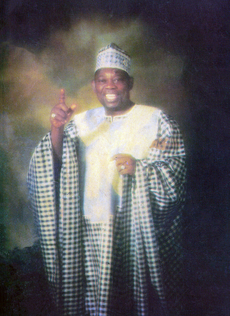

Abiola in 1993 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 August 1937 Abeokuta, Southern Region, British Nigeria (now in Ogun State, Nigeria) |

| Died | 7 July 1998 (aged 60) Abuja, Nigeria |

| Spouses | Simbiat Shoaga

(m. 1960; died 1992)Adebisi Oshin (m. 1974)Doyinsola Aboaba (m. 1981)

|

| Occupation |

|

Abiola ran for the presidency in 1993, for which the election results were annulled by then military president Ibrahim Babangida.[8] He would later die in detention after making an attempt to assert himself as the elected president.[9] Abiola was awarded the National honour Grand Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (GCFR), an honour awarded to only Nigerian heads of state, posthumously on 6 June 2018, by President Muhammadu Buhari and Nigeria's democracy day was changed to from 29 May to 12 June in his honour.[10][11][12]

Abiola was a personal friend of Ibrahim Babangida[13] and is believed to have supported Babangida's coming to power.[14]

Abiola's support in the June 1993 presidential election cut across all geo-political zones and religious divisions. He was among a few politicians to accomplish such influence during his time.[15] By the time of his death, he had become an unexpected symbol of democracy.[16]

Early life

editM. K. O. Abiola was born in Abeokuta, Ogun State,[2] to the family of Salawu[17] and Suliat Wuraola Abiola.[18] His father was a produce trader who primarily traded cocoa, and his mother traded in kola nuts.[19] His name, Kashimawo, means "Let us wait and see".[20] Moshood Abiola was his father's 23rd child, but the first of them to survive infancy, hence the name 'Kashimawo'. It was not until he was 15 years old that he was properly named Moshood by his parents.[citation needed]

Abiola attended African Central School, Abeokuta for his primary education.[21] As a young boy, he assisted his father in the cocoa trade,[22] but by the end of 1946, his father's business venture was failing, precipitated by the destruction of a cocoa consignment declared by a produce inspector to be of poor quality grade and unworthy for export and to be destroyed immediately.[23]

At the age of nine, Abiola started his first business, selling firewood gathered in the forest at dawn before school, to support his father and siblings.[24] Abiola founded a band at the age of 15, and would perform at various ceremonies in exchange for food. He was eventually able to require payment for his performances, and used the money to support his family and his secondary education at the Baptist Boys High School, Abeokuta. Abiola was the editor of the school magazine The Trumpeter, Olusegun Obasanjo was deputy editor.[25] At the age of 19, he joined the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons ostensibly because of its stronger pan-Nigerian origin compared with the Obafemi Awolowo-led Action Group.[26]

In 1960, Abiola obtained a government scholarship to study at the University of Glasgow,[27] where he later earned a degree in accountancy and qualified as a chartered accountant. He later became a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria (ICAN).[28]

Business career

editIn 1956, Abiola started his professional life as a bank clerk with Barclays Bank in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria.[25] After two years, he joined the Western Region Finance Corporation as an executive accounts officer, before leaving for Glasgow, Scotland, to pursue his higher education. He received a first-class degree in accountancy from Glasgow University,[29] and he also gained a distinction from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland. On his return to Nigeria, Abiola worked as a senior accountant at the University of Lagos Teaching Hospital, then went on to the US firm Pfizer, before joining the ITT Corporation, where he later rose to the position of vice-president, Africa and Middle East. Abiola spent a lot of his time, and made most of his money, in the United States, while retaining the post of chairman of the corporation's Nigerian subsidiary.

ITT

editWhile Abiola worked at the Nigerian subsidiary of Pfizer pharmaceuticals, his desire was to own some equity in the firm but the options available to him were not appealing.[30] He then applied to a job listing seeking a trained accountant, and it was during the interview that he found out the firm was ITT Corporation. Abiola was employed by the firm and one of his immediate responsibilities was to clear the backlog of debt owed to the firm by the military. An office meeting with the army's Inspector of Signals, Murtala Mohammed, to seek a resolution of the debts resulted in verbal argument heard by the Chief of Army Staff Hassan Usman Katsina.[30] The intervention of Katsina ended up being favourable to Abiola, as he was given a cheque to cover the debt. Abiola used his determination to clear the debts as a bargaining tool for more role in the company; initially he was able to remove the expatriate manager but was unable to get a requested 50 per cent equity in the Nigerian arm of ITT. Abiola subsequently established Radio Communication (RCN) as a side business,[31] new employees were trained in marketing of telecoms equipment and Abiola targeted the military who were replacing civil war-era equipment as business clients.[31] His marketing strategy proposed training of military personnel in the use of equipment so as to reduce reliance on outside vendors for maintenance, this strategy gained favor in a security conscious armed forces.[32] Abiola soon received a contract to supply hardware to the military that got the attention of ITT and he was offered 49 per cent equity ownership of its Nigerian arm.[30]

RCN went on to develop a static communications network for the armed forces signal unit and Nigeria's domestic satellite communications.[33] In 1975, ITT and partners secured a major contract to supply automatic telephone exchanges in a number of locations within the country.[30]

Other ventures

editIn addition to his duties throughout the Middle-East and Africa, Abiola invested heavily in Nigeria and West Africa. He set up Abiola Farms, Abiola Bookshops, Radio Communications Nigeria, Wonder Bakeries, Concord Press, Concord Airlines, Summit Oil International Ltd, Africa Ocean Lines, Habib Bank, Decca W.A. Ltd, and Abiola football club. He was also chairman of the G15 business council, president of the Nigerian Stock Exchange, patron of the Kwame Nkrumah Foundation, patron of the WEB Du Bois foundation, trustee of the Martin Luther King Foundation, and director of the International Press Institute.[34] In 1983, he teamed up with Shehu Musa Yar'Adua, Bamanga Tukur and Raymond Dokpesi to establish Africa Ocean Lines. The firm began operations in 1984, using chartered vessels, before acquiring two cargo ships in 1986 with a capacity for 958 TEUs. The shipping firm's route linked the major shipping ports along the West African coast with United Kingdom and Northern Europe.[21]

Involvement in politics

editAbiola's involvement in politics started early in his life when he joined the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) at the age of 19. In 1979, the military government kept its word and handed over power to the civilians. As Abiola was already involved in politics, he joined the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN) in 1980 and was elected the state chairman of his party. Re-election was done in 1983 and everything looked promising since the re-elected president was from Abiola's party and based on the true transition to power in 1979; Abiola was eligible to go for the post of presidential candidate after the tenure of the re-elected president. However, his hope to become the president was shortly dashed away for the first time in 1983 when a military coup d'état swept away the re-elected president of his party and ended civilian rule in the country.

Abiola was a member of Ansar Ud Deen organization in Nigeria. In the 1980s,[35] through his National Concord Newspaper Abiola supported Islamic causes including introduction of a Sharia Court of Appeal in Southwestern Nigeria and Nigeria's entry to the Organization of Islamic Countries. The support given the latter received less favorable response from some readers of the National Concord.[36] Notwithstanding, he was actively involved in the formation and activities of the National Sharia Committee. In 1984, he was given a title of Baba Adinni of Yorubaland by a committee of Muslim clerics. His support of Islam in Southern Nigeria earned him some recognition in the Northern region of the country.[37] In his hometown of Abeokuta, Abiola built a Quran training center which was named after his mother Zulihat Abiola.[13] After a decade of military rule, General Ibrahim Babangida came under pressure to return democratic rule to Nigeria. After an aborted initial primary, Abiola stood for the presidential nomination of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and beat Ambassador Baba Gana Kingibe and Alhaji Atiku Abubakar to secure the presidential nomination of the SDP ahead of the 12 June 1993, presidential elections. Abiola had managed to work his way out of poverty through hard work. He established Abiola bookshops to provide affordable, locally produced textbooks in the 1980s when imported textbooks became out of the reach of ordinary Nigerians as the naira was devalued. He also made available daily necessities such as rice and soap at affordable prices in the market.[38]

Presidential election

editPrimaries and campaign

editAbiola announced his candidacy for president in February 1993, this was after a previous round of presidential primaries had been cancelled by military President Babangida. His party of choice was SDP, though he was an outsider who was new to the partisan politics within the party which at the time was dominated by two major factions, People's Front(PF) and PSP.[39] Both SDP and its opposition, NRC held presidential primaries in March 1993. SDP's primaries was held in Jos and was largely a three-way contest between Abiola, Kingibe and Atiku even though there were more aspirants. Abiola was heavily supported by the People's Solidarity faction (PSP) within SDP while Atiku was supported by PF faction led by Yar'Adua and Kingibe was supported by a loose coalition of party members.[40] During the first ballot, Abiola was able to score a slim majority vote of 3,617 to Kingibe's 3,225.[41] A second round was contested two days later and Abiola again emerged victorious with a slim margin and he became the party's presidential candidate for the 12 June election.

Abiola's political message was an optimistic future for Nigeria, with slogans such as "Farewell to poverty", "At last! Our rays of Hope" and the "Burden of Schooling". His economic policy included negotiations with foreign creditors and better management of the country's international debts, in addition, increased cooperation with the foreign community while presenting himself as someone the international community can trust.[42]

Election

editFor the 12 June 1993, presidential elections, Abiola's running mate was his primary opponent Baba Gana Kingibe.[43] He defeated his rival, Bashir Tofa of the National Republican Convention. The election was declared Nigeria's freeest and fairest presidential election by national and international observers, with Abiola even winning in his Northern opponent's home state of Kano. Abiola won at the national capital, Abuja, the military polling stations, and over two-thirds of Nigerian states. Men of Northern descent had largely dominated Nigeria's political landscape since independence; Moshood Abiola, a Western[44] Muslim, was able to secure a national mandate freely and fairly, unprecedented in Nigeria's history. However, the election was annulled by Ibrahim Babangida, causing a political crisis which led to General Sani Abacha seizing power later that year.[45] During preparations for the 2011 Nigerian Presidential elections there were calls from several quarters to remember MKO Abiola.[46]

- Unofficial results

These are the unofficial results:[47][48]

| State | SDP (Abiola) | NRC (Tofa) | State | SDP (Abiola) | NRC (Tofa) | State | SDP (Abiola) | NRC (Tofa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abia | 105,273 | 151,227 | Enugu | 263,101 | 284,050 | Niger | 136,350 | 221,437 | ||

| Adamawa | 140,875 | 167,239 | Imo | 159,350 | 195,836 | Ogun | 425,725 | 59,246 | ||

| Akwa Ibom | 214,787 | 199,342 | Jigawa | 138,552 | 89,836 | Ondo | 883,024 | 162,994 | ||

| Anambra | 212,024 | 159,258 | Kaduna | 389,713 | 356,860 | Osun | 365,266 | 72,068 | ||

| Bauchi | 339,339 | 524,836 | Kano | 169,619 | 154,809 | Oyo | 536,011 | 105,788 | ||

| Benue | 246,830 | 186,302 | Katsina | 171,162 | 271,077 | Plateau | 417,565 | 259,394 | ||

| Borno | 153,496 | 128,684 | Kebbi | 70,219 | 144,808 | Rivers | 370,578 | 640,973 | ||

| Cross River | 189,303 | 153,452 | Kogi | 222,760 | 265,732 | Sokoto | 97,726 | 372,250 | ||

| Delta | 327,277 | 145,001 | Kwara | 272,270 | 80,209 | Taraba | 101,887 | 64,001 | ||

| Edo | 205,407 | 103,572 | Lagos | 883,965 | 149,432 | Yobe | 111,887 | 64,061 | ||

| sub-total | 2,134,611 | 1,918,913 | 2,740,611 | 1,992,649 | FCT | 19,968 | 18,313 | |||

| 3,465,987 | 2,040,525 | |||||||||

| Cumulative | 8,341,309 | 5,952,087 | ||||||||

Imprisonment

editIn June 1994, Abiola declared himself the lawful president of Nigeria[49] in the Epetedo area of Lagos island, an area mainly populated by (Yoruba) Lagos Indigenes. He had recently returned from a trip to win the support of the international community for his mandate. After declaring himself president, he was declared wanted on the orders of military President General Sani Abacha, who sent 200 police vehicles to bring him into custody.[50] His second wife, Alhaja Kudirat Abiola, was later assassinated in Lagos in 1996 after declaring public support for her husband. [51]

Moshood Abiola was detained for four years, largely in solitary confinement with a Bible, Qur'an, and fourteen guards as companions. During that time, Pope John Paul II, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and human rights activists from all over the world lobbied the Nigerian government for his release.[52] The sole condition attached to the release of Chief Abiola was that he renounce his mandate, something that he refused to do, although the military government offered to compensate him and refund his extensive election expenses. For this reason Chief Abiola became extremely troubled when Kofi Annan and Emeka Anyaoku reported to the world that he had agreed to renounce his mandate after they met with him to tell him that the world would not recognise a five-year-old election.[53][54]

Death

editMoshood Abiola died unexpectedly, shortly after the death of General Abacha, on the day that he was due to be released.[55] While meeting group of American diplomats including Thomas Pickering and Susan Rice at a government guesthouse in Abuja, Abiola fell ill and died. Rice had served tea to Abiola shortly before his collapse; despite evidence to the contrary there remains an enduring belief in Nigeria that she had poisoned Abiola.[56][57][58]

Independent autopsy carried out and witnessed by physicians and pathologists from the Nigerian government, Nigerian Medical Association, Canada, UK and the US found substantial evidence of longstanding heart disease.[59] General Abacha's Chief Security Officer, Hamza al-Mustapha has alleged that Moshood Abiola was in fact beaten to death and although Al-Mustapha claims to have video and audiotapes showing how Abiola was beaten to death, he has yet to come forward with the release of such tapes or how it was procured in the first place. Regardless of the exact circumstances of his death, it is clear that Chief Abiola received insufficient medical attention for his existing health conditions.[59]

Investigation

editA number of different perspectives exist on Abiola's death. Renowned writer and playwright Wole Soyinka in his autobiography You Must Set Forth at Dawn, categorically asserted that Abiola was presented with a poisoned cup of tea during his final interview with the BBC. He was certain about the fact that Abiola was poisoned, although information on what entities were behind the poisoning, have yet to come to light.[60]

Kofi Annan, the seventh Secretary General of the United Nations who had been in a meeting with Abiola at Abuja on 29 June 1998, mentioned that Abiola had been denied adequate medical care throughout his incarceration. This was in some corroboration with the findings of an international team of pathologists who posited a heart condition as the cause of death.[61]

The Human Rights Violation Investigation Commission of Nigeria, conducted a series of hearings aiming to discover the truth of events leading to the Abiola's death,[62] concluding that the Abubakar regime probably knew more than it revealed.[57]

Legacy

editChief M.K.O. Abiola's memory is celebrated in Nigeria and internationally.[63] Since his death, the Lagos State Government declares 12 June as a public holiday. In 2018, other states including Ogun, Oyo and Osun, announced 12 June as a public holiday to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the annulled 1993 presidential election.[64] 12 June remains a public holiday in Nigeria beginning 12 June 2019, it will be celebrated as democracy day, replacing 29 May.[65] Remembrance events are arranged across Nigeria.[66] MKO Abiola Stadium and Moshood Abiola Polytechnic were named in his honour, and there were calls for posthumous presidential recognition.[67] A statue, MKO Abiola Statue was erected in his honour.

M.K.O. Abiola was criticised by political activists and detractors. Controversy was caused by a song by Nigerian musician, Fela Kuti, a charismatic multi-instrumentalist musician, composer and human rights activist, famed for being the pioneer of Afrobeat music and a controversial figure due to his unusual lifestyle and apparent drug use.[68] It is believed that Kuti had entered into an acrimonious dispute relating to a contract with M.K.O. Abiola's record label.[69] He used the abbreviation of International Telephone & Telegraph (IT&T) in a song criticising big multinational corporations. The song, ITT, accuses such companies of draining Africa's resources and says "they start to steal money Like Obasanjo and Abiola".[70]

On 29 May 2012, former president Goodluck Jonathan, announced that the famous University of Lagos will be renamed in memory of Abiola as Moshood Abiola University of Lagos (MAULAG). This received a negative reaction by both students, Alumni and members of public resulting in an abrupt reversal.[71]

12 June declared Democracy Day

editOn 6 June 2018, Muhammadu Buhari, President of Nigeria declared 12 June as the new date for the celebration of Democracy Day. Nigeria's Democracy Day was formally celebrated every 29 May, the day in 1999 that former military Head of State, Abdulsalami Abubakar, handed over power to an elected president, Olusegun Obasanjo of the People's Democratic Party (PDP) and the date when, for the second time in the history of Nigeria, an elected civilian administration took over from a military government.[72]

On 6 June 2018, Muhammadu Buhari in a public statement changed the Democracy Day to 12 June in honor of the 12 June 1993, presidential election and it's winner, Moshood Abiola, who died in prison. Buhari's statement partly read: "for the past 18 years, Nigerians have been celebrating May 29, as Democracy Day. That was the date when, for the second time in our history, an elected civilian administration took over from a military government. The first time this happened was on 1 October 1979. But in the view of Nigerians, as shared by his administration, June 12, 1993, was far more symbolic of democracy in the Nigerian context than May 29 or even the October 1. June 12, 1993 was the day when Nigerians in millions expressed their democratic will in what was undisputedly the freeest, fairest and most peaceful elections since our independence. The fact that the outcome of that election was not upheld by the then military government doesn't distract from the democratic credential of that process. Accordingly, after due consultation, the Federal Government has decided, henceforth, June 12 will be celebrated as Democracy Day. Therefore, the government has decided to award posthumously the highest honour of the land GCFR, to the late Chief M.K.O. Abiola, the presumed winner of the June 12, 1993 cancelled election".[73]

On 11 June 2019, Muhammadu Buhari assented to a Bill amending 29 May previously set aside as a public holiday for the celebration. The public holiday amendment Act was passed by the National Assembly of Nigeria following a Bill introduced and sponsored by Kayode Oladele, Human Rights Lawyer and Member of the House of Representatives ( Eighth Assembly) representing Yewa North/Imeko-Afon Federal Constituency of Ogun State.[74][75]

Awards and honours

editMoshood Abiola was twice voted international businessman of the year,[76] and received numerous honorary doctorates from universities all over the world. In 1987 he was bestowed with the golden key to the city of Washington, D.C., and he was bestowed with awards from the NAACP and the King center in the US, as well as the International Committee on Education for Teaching in Paris, among many others.

In Nigeria, the Oloye Abiola was made the Aare Ona Kakanfo of Yorubaland, the highest chieftaincy title available to commoners among the Yoruba. At the point when he was elevated, the title had only been conferred by the tribe thirteen times in its long history. This in effect rendered Abiola the ceremonial War Viceroy of all of his tribespeople. According to the folklore of the tribe as recounted by the Yoruba elders, the Aare Ona Kakanfo is expected to die a warrior in the defence of his nation to prove himself in the eyes of both the divine and the mortal as having been worthy of his title.[77][78]

He was posthumously awarded the third highest national honour, the Commander of the Federal Republic, in 1998.[79]

He was also awarded the highest national honor, the Grand Commander of the Federal Republic – or GCFR – in 2018. The date of the annulled election, 12 June, was also made Nigeria's Democracy Day.[80]

Personal life

editMoshood Abiola married many wives;[81][4] notable among them are Simbiat Atinuke Shoaga in 1960,[4] Kudirat Olayinka Adeyemi in 1973, Adebisi Olawunmi Oshin in 1974,[1] Doyinsola (Doyin) Abiola Aboaba in 1981, Modupe Onitiri-Abiola[5][4] and Remi Abiola. He fathered many children.[2][1] In 2024, Modupe Onitiri-Abiola organized a failed coup attempt in Oyo State; the rest of the Abiola family denounced her actions.[3]

Philanthropy

editMoshood Abiola sprang to national and international prominence as a result of his philanthropic activities. The Congressional Black Caucus of the United States of America issued the following tribute to Moshood Abiola:[82]

Because of this man, there is both cause for hope and certainty that the agony and protests of those who suffer injustice shall give way to peace and human dignity. The children of the world shall know the great work of this extraordinary leader and his fervent mission to right wrong, to do justice, and to serve mankind. The enemies which imperil the future of generations to come: poverty, ignorance, disease, hunger, and racism have each seen effects of the valiant work of Chief Abiola. Through him and others like him, never again will freedom rest in the domain of the few. We, the members of the Congressional Black Caucus salute him this day as a hero in the global pursuit to preserve the history and the legacy of the African diaspora.[83]

From 1972 until his death, Moshood Abiola was conferred with 197 traditional titles by 68 different communities in Nigeria, in response to his having provided financial assistance in the construction of 63 secondary schools, 121 mosques and churches, 41 libraries, 21 water projects in 24 states of Nigeria, and he was grand patron to 149 societies or associations in Nigeria. In addition to his work in Nigeria, Abiola supported the Southern African Liberation movements from the 1970s, and he sponsored the campaign to win reparations for slavery and colonialism in Africa and the diaspora. He personally communicated with every African head of state, and every head of state in the black diaspora to ensure that Africans would speak with one voice on the issues.[84]

Notes

edit- ^ "Aare Ona Kankafo" was the title of the supreme military commander of the Oyo Empire

References

edit- ^ a b c d e The International Who's Who, 1997–98. Vol. 61. Europa Publications. 1997. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-857-4302-26.

- ^ a b c "Moshood Abiola". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ a b Adeyemi, Ibrahim (23 April 2024). "The Curious Journey Of Woman Who Declared Yoruba Independence From Nigeria". HumAngle. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d Duval Smith, Alex (10 July 1998). "Abiola's warring wives mirror Nigeria's divides". The Guardian. The United Kingdom. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ a b "REMEMBERING ABIOLA, 15 YEARS AFTER". National Mirror. 6 July 2013. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Are Ona Kakanfo's origin, myth and power by Prof. Banji Akintoye – Vanguard News". Vanguard News. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola | Nigerian entrepreneur and politician". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, Janice. Nigeria in Pictures, p. 70.

- ^ FIJ (12 June 2023). "RELIVE: How MKO Abiola Declared Himself 'President and Commander-in-Chief'". Foundation For Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "UPDATED: Buhari declares June 12 Democracy Day, honours MKO Abiola with GCFR". Punch Newspapers. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "BREAKING: Buhari declares June 12 Democracy Day to honour Abiola". Premium Times Nigeria. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Posts tagged as #mkoabiola". picbabun.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Rufai, Misbahu (11 May 1990). A man called MKO. Muslim Journal.

- ^ Maier, Karl (2002). This house has fallen : Nigeria in crisis. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 9780786730612. OCLC 813166032.

- ^ Holman, Michael, and Michela Wrong. "Chief Moshood Abiola Presumed Poll Winner Managed to Straddle the Regional and Religious Split in a Way Few Nigerian Politicians Can Do Today". Financial Times, 8 July 1998, p. 3. Financial Times Historical Archive.

- ^ "A thread written by @JoyLydia10". threader.app. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "The legend called M.K.O". The Guardian Nigeria News – Nigeria and World News. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Adenekan, Sulaiman. "President Muhammadu Buhari receives elders, leaders from Ogun State on gratitude visit over honour bestowed on M.K.O Abiola". Trade Newswire. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Abiola 1992, p. 127.

- ^ "Kashimawo - Nigerian.Name". www.nigerian.name. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ a b Nigeria: transport, aviation & tourism : information handbook directory & who's who. Lagos: Media Research Publications. 1988. OCLC 26830979.

- ^ "Victory In Death... MKO Abiola's Travails, Triumphs In Retrospect". The Guardian Nigeria News – Nigeria and World News. 3 January 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Abiola 1992, p. 128.

- ^ Abiola 1993, pp. 429–433.

- ^ a b Abiola 1993, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ogunbiyi and Amuta (eds), Legend of our Time: The Thoughts of M.K.O. Abiola, Tanus Press, p. 5.

- ^ "JUNE 12 SPECIAL: Short Profile of Late Chief MKO Abiola". Sahara Reporters. 12 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola | Nigerian entrepreneur and politician". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Moshood Abiola at aaregistry.org

- ^ a b c d Forrest, Tom (1994). The advance of African capital : the growth of Nigerian private enterprise. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. pp. 99–103. ISBN 0813915627. OCLC 30355123.

- ^ a b Abiola 1992, p. 145.

- ^ Abiola 1992, p. 147.

- ^ Abiola 1992, p. 150.

- ^ "Curriculum Vitae". Hope-rises.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Reichmuth, Stefan (January 1996). "Education and the Growth of Religious Associations among Yoruba Muslims: The Ansar-Ud-Deen Society of Nigeria". Journal of Religion in Africa.

- ^ Dominic, Okereke (July 2012). Africa's quiet revolution : (observed from Nigeria). Northampton, UK. p. 312. ISBN 9781908341877. OCLC 932127559.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Loimeier, Roman (1997). Islamic reform and political change in northern Nigeria. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. pp. 321–322. ISBN 0810113465. OCLC 35792337.

- ^ University of Connecticut: Summer advance, July 1994.

- ^ Emelifeonwu 1999, p. 237.

- ^ Emelifeonwu 1999, p. 239.

- ^ Emelifeonwu 1999, p. 240.

- ^ Opeibi, Olusola Babatunde (2011). Discourse strategies in political campaigns in Nigeria. ]: Lap Lambert Academic Publishing. pp. 55–57, 277. ISBN 978-3845416779. OCLC 991643499.

- ^ "Democracy Day: MKO Abiola in eyes of history 27 years later". Premium Times. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Abeokuta | Location, History, Facts, & Population". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Chief Moshood Abiola Memorial Service". David-kilgour.com. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "MKO: Is June 12 also Dead?". South Elevation: Viewpoint. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Okogba, Emmanuel (19 June 2018). "Anniversary of June 12 presidential election (5)". Vanguard News Nigeria. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Emelifeonwu, David C. (1999). Anatomy of a failed democratic transition : the case of Nigeria, 1985–1993 (Thesis).

- ^ "Imprisoned Political Figure Dies in Nigeria". Washington Post. 4 July 2024.

- ^ TheCable (12 June 2017). "The speech that got Abiola arrested – and 'killed'". TheCable. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ NWOKWU, RUTH (4 June 2024). "Kudirat Abiola Made Nigeria's Democracy Possible - Atiku". Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "CNN – Vatican presses Nigeria for dissidents' release – March 21, 1998". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "BBC News | Africa | Annan 'to meet Abiola'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "BBC News | Africa | Abiola letter accuses Annan". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa 1993–1999", Wayne Madsen, Edwin Meller Press

- ^ "BBC News – Africa – Abiola's death – an eyewitness account". news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b Bourne, Richard (2015). Nigeria : a new history of a turbulent century. London: Zed Books. p. 201. ISBN 9781780329062.

- ^ Rice, Susan E. (2019). Tough love : my story of the things worth fighting for. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1501189975.

- ^ a b "7/11/98: Nigeria: Autopsy Results-Chief M.K.O. Abiola". 1997-2001.state.gov. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Soyinka, Wole (2006). You Must Set Forth at Dawn. USA: Random House. pp. 59–69. ISBN 9780375503658.

- ^ Annan, Kofi (2012). Interventions: A Life in War and Peace. USA: The Penguin Press. pp. 340–345. ISBN 9781846142970.

- ^ Tay (24 July 2021). "Oputa Panel: Major Aliyu Recounts Eye Witness Events Leading To MKO Abiola's Death Under His Watch". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "Speech in honour of MKO Abiola". Board of African Studies Association.

- ^ "Lagos, Oyo, Osun govts declare June 12 public holiday". Tribune Online. 10 June 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Kanu, Daniel (13 June 2000). "Nigeria: June 12 Holiday to Honour Abiola, Says Tinubu". The Post Express (Lagos). Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "June 12 Remembrance 2011 | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Kazeem Ugbodaga, "12 Years After: Nigerians Celebrate MKO Abiola", PM News, 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Fela Kuti's Nigeria: 10 years on", BBC News, 2 August 2007.

- ^ Iruemobe, Busayo (12 June 2018). "MKO Abiola: Why Fela Kuti no gree see eye to eye wit Bashorun". BBC Pidgin. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Fela Kuti – I.T.T. (International Thief Thief) Lyrics | SongMeanings". SongMeanings. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ Adekunle (21 February 2013). "UNILAG name change: Jonathan makes u-turn". Vanguard News Nigeria. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Democracy Day: FG declares Friday, June 12, public holiday". 8 June 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Buhari declares June 12 Democracy Day, honours Abiola with GCFR". Punch Newspapers. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Reps passes Bill to make June 12, Democracy Day". Vanguard News. 17 May 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Fresh pressure as Buhari signs bill declaring June 12 Democracy Day". guardian.ng. 11 June 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ 10 Quick Facts About M.K.O Abiola • Channels Television, retrieved 11 June 2018

- ^ "The Contemporary Politics and its". Yoruba.org. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ news bbc, world/Africa.

- ^ "Nigerian national awards | Nigerian Muse". www.nigerianmuse.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "Buhari honours MKO Abiola, declares June 12 Democracy Day". Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ Rahnan, Tunde. "Nigeria: MKO Abiola's Will – 25 Children Fail DNA Test". Allafrica. Thisday. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Ogunbiyi and Amuta (eds), p. 16.

- ^ "June 12: Full speech of M.K.O Abiola that got him imprisoned, killed – Daily Post Nigeria". Daily Post Nigeria. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "eliesmith: Senator A.S. Yarima: Reparation For Africa Have To Be Review". Eliesmith.blogspot.com. 10 August 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

Sources

edit- Abiola, M. K. O. (1992). Reparations : a collection of speeches. Lome, Togo: Linguist Service. ISBN 9783175505. OCLC 28212732.

- Abiola, Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (1993). Yemi Ogunbiyi; Chidi Amuta (eds.). Legend of Our Time: The Thoughts of M.K.O. Abiola. Tanus Communications. ISBN 978-978-31824-1-7.

External links

editMedia related to Moshood Abiola at Wikimedia Commons