The Invisible Man is a 1933 pre-Code American science fiction horror film directed by James Whale loosely based on H. G. Wells's 1897 novel, The Invisible Man, produced by Universal Pictures, and starring Gloria Stuart, Claude Rains and William Harrigan. The film involves a stranger named Dr. Jack Griffin (Rains) who is covered in bandages and has his eyes obscured by dark glasses, the result of a secret experiment that makes him invisible, taking lodging in the village of Iping. Never leaving his quarters, the stranger demands that the staff leave him completely alone until his landlady and the villagers discover he is invisible. Griffin goes to the house of his colleague, Dr. Kemp (William Harrigan) and tells him of his plans to create a reign of terror. His fiancée Flora Cranley (Gloria Stuart), the daughter of his employer Dr. Cranley (Henry Travers), soon learn that Griffin's discovery has driven him insane, leading him to prove his superiority over other people by performing harmless pranks at first and eventually turning to murder.

| The Invisible Man | |

|---|---|

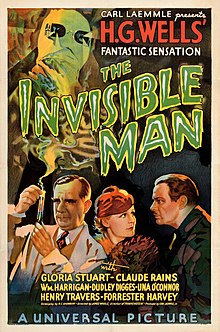

Theatrical release poster by Karoly Grosz[1] | |

| Directed by | James Whale |

| Screenplay by | R. C. Sherriff[2] |

| Based on | The Invisible Man 1897 novel by H. G. Wells[2] |

| Produced by | Carl Laemmle Jr.[2] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Arthur Edeson |

| Edited by | Ted Kent[2] |

| Music by | Heinz Roemheld |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures Corp. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 70 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[3] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $328,033 |

The Invisible Man was in development for Universal as early as 1931 when Richard L. Schayer and Robert Florey suggested that Wells' novel would make a good follow-up to the studio's horror film hit Dracula. Universal opted to make Frankenstein in 1931 instead. This led to several screenplay adaptations being written and a number of potential directors including Florey, E.A. Dupont, Cyril Gardner, and screenwriters John L. Balderston, Preston Sturges, and Garrett Fort all signing on to develop the project intending it to be a film for Boris Karloff. Following Whale's work on The Old Dark House starring Karloff and The Kiss Before the Mirror, Whale signed on and his screenwriting colleague R.C. Sherriff developed a script in London. Production began in June 1933 and ended in August with two months of special effects work done following the end of filming.

On the film's release in 1933, it was a great financial success for Universal and received strong reviews from several trade publications, and likewise from The New York Times, which deemed it one of the best films of 1933. The film spawned several sequels that were relatively unrelated to the original film in the 1940s. The film continued to receive praise on re-evaluations by critics such as Carlos Clarens, Jack Sullivan, and Kim Newman, as well as being listed as one of their favorite genre films by filmmakers John Carpenter, Joe Dante, and Ray Harryhausen. In 2008, The Invisible Man was selected for the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[4]

Plot

editOn a snowy night, a stranger, his face swathed in bandages and his eyes obscured by dark goggles, takes a room at The Lion's Head Inn in the English village of Iping in Sussex. The man demands to be left alone. Later, the innkeeper, Mr. Hall, is sent by his wife to evict the stranger after he has made a huge mess in his room while doing research and has fallen behind on his rent. Angered, the stranger throws Mr. Hall down the stairs. Confronted by a policeman and some local civilians, he removes his bandages and goggles, revealing he is invisible. Laughing maniacally, he takes off his clothes, making himself completely undetectable, and drives off his tormentors before fleeing into the countryside.

The stranger is Dr. Jack Griffin, a chemist who discovered the secret of invisibility while conducting a series of tests involving an obscure drug called monocaine. Flora Cranley, Griffin's fiancée and the daughter of Griffin's employer, Dr. Cranley, becomes distraught over Griffin's long absence. Cranley and his other assistant, Dr. Kemp, search Griffin's empty laboratory, finding only a single note in a cupboard. Cranley becomes concerned when he reads it. The note has a list of chemicals, including monocaine, which Cranley knows is extremely dangerous; an injection of it drove a dog mad in Germany. Griffin, it seems, is unaware of this. Cranley deduces Griffin may have learned about monocaine in English books printed before the incident that describe only its bleaching power.

On the evening of his escape from the inn, Griffin turns up at Kemp's home. He forces Kemp to become his visible partner in a plot to dominate the world through a reign of terror, beginning with "a few murders here and there". They drive back to the inn to retrieve his notebooks on the invisibility process. Sneaking inside, Griffin finds a police inquiry underway, conducted by an official who believes it is all a hoax. After securing his books, Griffin angrily attacks and kills the officer.

Back home, Kemp calls Cranley, asking for help, and then the police. Flora persuades her father to let her come along. In her presence, Griffin becomes more placid and calls her "darling". When he realizes Kemp has betrayed him, his first reaction is to get Flora away from danger. After promising Kemp that at 10 o'clock the next night he will murder him, Griffin escapes and goes on a killing spree. He causes the derailment of a train, resulting in a hundred deaths, and throws two volunteer searchers off a cliff. The police offer a reward for anyone who can think of a way to catch him.

Feeling that Griffin will try to fulfill his promise, the chief detective in charge of the search uses Kemp as bait and devises various clever traps. Trying to protect Kemp, the police disguise him in a police uniform and let him drive his car away from his house. Griffin, however, is hiding in the back seat of the car, surprising Kemp; he tells Kemp that he was also following him all day while committing his crimes. He overpowers Kemp and ties him up in the front seat. Griffin then sends the car down a steep hill and over a cliff where it explodes on impact, killing Kemp.

A snowstorm forces Griffin to seek shelter in a barn where he falls asleep. Later a farmer enters and spots movement in the hay where Griffin is sleeping. He notifies the police, who rush out to the farm and surround the barn. They set fire to the building, which forces Griffin to come out, leaving visible footprints in the snow. The chief detective opens fire, mortally wounding Griffin. He is taken to the hospital where, hours later, a surgeon informs Dr. Cranley that Griffin is dying and asking to see Flora. On his deathbed, Griffin remorsefully admits to Flora, "I meddled in things that man must leave alone". As he dies, his body quickly becomes visible again.

Cast

editCast sourced from the book Universal Horrors:[2]

- Gloria Stuart as Flora Cranley

- Claude Rains as Dr. Jack Griffin

- William Harrigan as Dr. Arthur Kemp

- Henry Travers as Dr. Cranley

- Una O'Connor as Jenny Hall

- Forrester Harvey as Herbert Hall

- Dudley Digges as Chief of Detectives

- E. E. Clive as Police Constable Jaffers

- Dwight Frye as Reporter

- Merle Tottenham as Millie

- Robert Brower as the farmer (uncredited)

Production

editBackground

editFollowing the success of Dracula (1931), Richard L. Schayer and Robert Florey suggested to Universal Pictures as early as 1931 that an adaptation of H. G. Wells' The Invisible Man would make a suitable follow-up.[2] Both Carl Laemmle and Carl Laemmle Jr. opted to make a film adaptation of Frankenstein (1931) instead.[2] While Frankenstein was shooting, Universal bought the rights to The Invisible Man from Wells on September 22, 1931, for $10,000;[5] he demanded script approval from Universal.[6] Universal had purchased the rights to the Philip Wylie 1931 novel The Murderer Invisible, intending to lift some of the more gruesome elements from it to incorporate into Wells' story.[7][5]

The director first set up for the project was James Whale, whom Laemmle Jr. had great faith in. He had directed R. C. Sherriff's play Journey's End in London and New York and the 1930 film Journey's End.[8] Following the release of Frankenstein, which would break box office records across the United States, Universal had the film's star Boris Karloff signed to a five-year contract.[9] On December 29, 1931, the Los Angeles Record stated that Karloff's next film would be The Invisible Man.[10] By January 28, 1932, Whale had left the project, wary of being tagged as a "horror" director. This left Karloff as the only cast member of a film with neither a script nor a director.[11]

Pre-production

editThe first director set to replace Whale was Robert Florey, whose film Murders in the Rue Morgue was released in February 1932.[2][12] By April 9, Florey had a draft of The Invisible Man co-written with Garrett Fort who had contributed to the scripts of both Dracula and Frankenstein.[12] Based mostly on Wylie's The Murderer Invisible,[12] their outline included plot elements such as an invisible octopus, invisible rats, and blowing up Grand Central Station.[12] Unwilling to wait while Florey worked out the script and the film's technical difficulties, Universal made The Old Dark House (1932) Karloff's next feature with Whale as director.[2] Whale had decided to return to horror features following the financial failure of his film The Impatient Maiden (1932).[12] By June 1932, producer Sam Bischoff left Universal to set up his own independent studio. Florey accepted Bischoff's invitation to join him and also left Universal.[2] By June 6, John L. Balderston, whose name had appeared in the credits of Dracula and Frankenstein, submitted a screenplay for The Invisible Man in collaboration with the film's new director Cyril Gardner.[2][13] This was Balderston's third attempt at the script based primarily on Wylie's novel.[13] In mid-1932, Universal writers John Huston and studio scenario editor Richard Schayer attempted new treatments for the film.[14] By July 18, there was still no officially approved script and Universal loaned Karloff to MGM to shoot The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932).[15]

By November, following the release of The Old Dark House, Whale was again set to be the director of The Invisible Man with a new script being written by Preston Sturges.[16] Sturges' script involved a Russian chemist who makes a madman invisible to wreak vengeance on Bolsheviks who have destroyed his family. After working on the script for eight weeks, Sturges handed in his screenplay; Universal fired him the next day.[17] Sherriff described Sturges' draft as "a sort of transparent Scarlet Pimpernel".[7] On November 5, it was reported that Karloff was to star in a film titled The Wizard to be directed by E.A. Dupont, while Whale would film Karloff in The Invisible Man in early 1933.[18] Whale had also written his own treatment for the film,[18] which is described by historian Gregory Mank as inspired by both The Phantom of the Opera and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde interjected with religious touches like those in his films Frankenstein and The Old Dark House.[19] After Wells rejected this draft, Whale left The Invisible Man again.[18] On January 17, 1933, Universal reported a loss of $1,250,283 in 1932 and planned to shut down for six to eight weeks after current productions had finished shooting.[20] While Whale directed The Kiss Before the Mirror (1933), E.A. Dupont's project The Wizard was never filmed and he became the next person set to direct The Invisible Man.[21][22] John Weld was signed to write the film's script and browsed through several rejected drafts, including one by Laird Doyle.[7] Weld asked for a copy of Wells' novel from Universal. As they did not have a copy, he got his own to use for source material.[23] Yet another new writer was attached to write the script by February 3. R.C. Sherriff was the screenwriter and Whale was once again set to direct.[7][23] Sherriff worked on the script at his home in London and disregarded Universal's request he draw material from Wylie's The Murderer Invisible and the previous draft scripts.[7] Universal Studios closed down on February 13 with only executives and a skeleton crew remaining on the payroll.[24] Universal laid off Whale for twelve weeks before he directed The Invisible Man.[25] Universal reported they planned on having Karloff return to The Invisible Man in May.[26] After Universal reopened in May, they released his new film The Kiss Before the Mirror to critical acclaim, but it was among the studio's lowest-grossing films in Los Angeles and New York.[26]

While Sherriff was completing the script, on June 1, several trade papers announced Karloff was leaving the picture.[27] The Hollywood Reporter reported on May 16 that Karloff was "definitely out," while Variety reported he had left the project by June 1 citing salary issues.[28] Wells approved of Sherriff's script, including changes such as having Griffin's drug monocane not just make him invisible, but also drive him into insanity.[29][27] Sherriff recalled that "[Wells] agreed with me entirely that an invisible lunatic would make people sit up in the cinema more quickly than a sane man".[29] Sherriff completed his draft and returned to Hollywood in July 1933.[7] Some sources, including Phil Hardy's book Science Fiction and Carlos Clarens' An Illustrated History of the Horror Film,[30][31] state that Wylie revised Sherriff's final draft, while the authors of the book Universal Horrors found no evidence to support this claim.[7]

Casting

editWhale considered Colin Clive for the film's title role, but he also thought of actor Claude Rains, whom he met at a London performance of The Insect Play in 1923.[7][32] At the time, Rains' career was as a stage actor in New York and London and Universal discouraged Whale from casting him, not wanting an unknown actor in the lead.[7] Rains had been earning so little money from his work on stage he was considering leaving the theatre completely as he had recently bought a farm in New Jersey.[33] Whale had tracked down a screen test Rains had done for A Bill of Divorcement, which Rains later described as "terrible", saying he was "all over the place! I knew nothing about screen technique, of course, and just carried on as if I was in an enormous theatre. When I saw the test, I was shocked and frightened".[34] After viewing the screen test, Whale wanted Rains as the lead and had him do another reading of the scene where Griffin boasts to Dr. Kemp of his plans to rule the world.[7][34] Universal approved of the screen test and signed Rains for a two-picture deal, including top billing in The Invisible Man.[35] While filming, Rains asked Whale to let him act more emotionally, asking him if he could "try to express something with [his] eyes". Whale replied: "But Claude, old fellow, what are you going to do it with? You haven't any face!"[36]

Whale did not fully divulge the details of the role to Rains but sent him to studio labs to prepare for special effects, where molds and casts of his head were made.[37] Gloria Stuart, who had worked with Whale in The Old Dark House and The Kiss Before the Mirror acted in the role of Flora Cranley.[38] Stuart reflected on working with Rains and found him to be difficult, saying: "He was molto difficile, he was an 'actor's actor' and he didn't really give".[38] The role of Dr. Arthur Kemp was set for Chester Morris. He left the project when he learned it was unflattering.[35] William Harrigan was cast as his replacement. He had worked with Rains in a 1932 stage version of The Moon in the Yellow River.[39] Other actors cast in the film were on the verge of Hollywood success, including Walter Brennan playing a man whose bicycle is stolen, and John Carradine as an informer.[40]

Among the crew, cinematographer Arthur Edeson had worked with Whale on Waterloo Bridge (1931), Frankenstein, The Impatient Maiden, and The Old Dark House.[41] Heinz Roemheld composed the score for The Invisible Man. He would later score Dracula's Daughter (1936), The Black Cat (1934), and win an Academy Award for Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942).[42] Roemheld was a former concert pianist, and conductor who had impressed Carl Laemmle with his accompaniment to screenings of the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera.[43][44] Roemheld left Universal in 1931 but returned in 1933 to score The Invisible Man.[44] The film's score is only heard in the opening, during the last seven minutes of the film, and while the closing credits run.[45] The film's score was recycled in later Universal productions, a common practice during the 1930s.[46] The music is heard again in Werewolf of London (1935), The Black Cat, and the two film serials Flash Gordon (1936) and Buck Rogers (1939).[46]

Filming

editPrincipal photography of The Invisible Man began at the end of June 1933,[47] and concluded in late August.[47] All of the special effects shots were filmed in what Gloria Stuart recalled as "in utmost secrecy" during production.[48] The special effects work took another two months to complete.[47] Universal press clips falsely claimed that the invisibility effects were optical effects done with mirrors.[49] Whale worked closely with John P. Fulton on the film's special effects.[50] Fulton revealed how the effects were done in the September 1934 issue of American Cinematographer, stating they had been shot against a completely black set with walls and floors covered in black velvet to make it non-reflective.[50][51] The actor was then covered head to foot with black velvet tights and wore whatever clothes he required for the scene.[50][51] With this negative, a print was made, and a duplicate negative was made to serve as mattes for printing. Then with an ordinary printer, they made a composite first printing of the positive of the background and normal action, using the negative matte to mask the area where the invisible man was to move.[50][51] Fulton said the principal difficulty of this was matching the lighting on the visible clothes shot with the general lighting used in the scenes and fixing small imperfections such as the scenes with eye-holes which were touched up in the film frame by frame with a brush and opaque dye.[50][51] John P. Fulton wrote, "We photographed thousands of feet of film and many "takes" of the different scenes, and approximately 4,000 feet of film received individual hand-work treatment in some degree, making approximately 63,000 frames which were individually retouched in this manner!"[52]

For other scenes, where Rains is unwrapping the bandage from his head for the villagers, Rains' own head is hidden below his collar, and the bandages are being taken off a thin wireframe.[53] Other effects involving props moving "by themselves" are done with wires pulled by booms or dollies.[53]

John P. Fulton explained the mechanics of the scene where footprints in snow reveal the Invisible Man's presence and path: "As other actors appeared in these shots, we could not make the footprints appear by using 'stop-motion,' so instead we dug a trench along the line where we wanted the footprints, and covered the trench with a board, in which the footprints had been cut. The footprint-openings were filled with the wooden outlines which had been cut to make the footprints; these were supported by pegs extending to the bottom of the trench, and a rope was looped around the pegs, so that pulling upon it would pull out the pegs, and cause the outlines to drop away from the board. The board was then covered with the snow-material; and as we shot the scene, we pulled on the rope, pulling out the pegs, and causing the snow to drop down through the holes, giving us perfect footprints."[54]

The film's final cost after Fulton finished the special effects was $328,033.[45]

Release

editFollowing the October 26 press screening, a reviewer for The Hollywood Reporter praised the film, declaring it "a legitimate offspring of the family that produced Frankenstein and Dracula" and predicted it would "fare better [...] than either of its predecessors".[45] The review specifically praised the work of Whale, Rains, and Sherriff.[56] The Invisible Man was screened on October 31, 1933, at the Kiva theatre in Greeley, Colorado.[57] Other premiere screenings took place in Chicago, where it premiered at the Palace Theatre on November 10, in New York at the Roxy Theatre on November 17, and Los Angeles at the RKO-Hill Street Theatre on November 17.[58] Universal Pictures distributed the film theatrically.[2][3] When the film played in Los Angeles at RKO-Hill Street, it played to nearly empty houses.[59] It performed far better at New York's Roxy, where it earned $26,000 in its first three days.[59] It broke records at the New York theatre for their 1932–1933 season.[50] 80,000 patrons saw the film in four days, with $42,000 being collecting there during the week, leading to the film to continue screening for a second week.[50] The film moved to two theatres in New York: The Radio City Roxy and the RKO Palace, where it continued to perform well.[60] The Invisible Man never performed well in Los Angeles during its initial release, where it grossed $4,300 in one week.[60] Overall, the authors of Universal Horrors described the film as a "big success" at the box office.[50] The film opened in London on January 28, 1934, at the Tivoli Theatre where it was also an enormous hit.[60] The total gross of The Invisible Man is unknown.[61]

Home media

editIn 2000, Universal released The Invisible Man on VHS and DVD as part of their Classic Monster Collection, a series of releases of Universal Classic Monsters films.[62][63] In 2004, Universal released The Invisible Man: The Legacy Collection on DVD as part of the Universal Legacy Collection.[64][65] This two-disc release includes The Invisible Man, along with The Invisible Man Returns (1940), The Invisible Woman (1940), Invisible Agent (1942), and The Invisible Man's Revenge (1944), as well as a short documentary Now You See Him: The Invisible Man Revealed, hosted by film historian Rudy Behlmer.[64][65] In 2012, Universal Studios celebrated its 100th anniversary and released a restored version of The Invisible Man as it had done for Dracula, Frankenstein, and Bride of Frankenstein.[66] Universal engaged Technicolor Creative Service to prepare a new print, combined with Universal's preservation acetate dupe negative and a nitrate dupe found at the British Film Institute.[66] This new print featured long-missing frames, and digital repair of scratches, stains, and improved sound.[67] In the same year, The Invisible Man was released on Blu-ray as part of the Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection box set, which includes nine films from the Universal Classic Monsters series.[68] The film received a standalone Blu-ray release in 2013, followed by a six-film release of the films in the Invisible Man series in a Complete Legacy Collection on Blu-ray.[64] Universal Pictures Home Entertainment released the film on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on October 5, 2021.[69]

Reception

editContemporary

editMordaunt Hall of The New York Times and the critic credited as "Char" in Variety commented on the originality of the material, with Hall finding the film to be a "remarkable achievement" that surprised him that it was not attempted earlier.[70] "Char." reflected on this, stating it brought "something new and refreshing in film frighteners".[71][72] Critics also praised the crew, such as Thornton Delehanty of The New York Post who referred to the film as "one of the best thrillers of the year", complimented the work of Sherriff and the "quality of awesomeness and suspense" Whale provided.[38] Kate Cameron of the New York Daily News gave the film a three and a half star rating, praising Rains's performance, stating, "his voice carrying a sinister note that is very effective in this kind of horror role" and declared the film to be one that "should not be missed".[38] More general praise came from other publications from Film Daily wrote: "It will satisfy all those who like the bizarre and the outlandish in their film entertainment"[73] and John Mosher of The New Yorker called the film a "bright little oddity".[74] The New York Times placed the film at number nine on its 1933 Ten Best list.[75]

Retrospective

editIn his 1967 book The Illustrated History of Horror and Science-Fiction Films, Carlos Clarens praised the film, stating that "the scene where Griffin first flaunts his invisibility is the kind of cinema magic that paralyzes disbelief and sets the most skeptical audience wondering".[76] Clarens noted that "not only is the show a technical tour de force, The Invisible Man also contains some of the best dialogue ever written for a fantastic film".[76] Jack Sullivan wrote in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986) that the gags in The Invisible Man were "the opposite of strained", noting that Griffin singing wearing only his pyjama pants was "a piece of unabashed prankishness, but it's also something beyond that: the sudden eye-opening enchantment of the scene is worthy of Grimms or L. Frank Baum" concluding the scene was "the perfect image to define Whale's lightly horrific fairy-tale magic".[77] In Phil Hardy's 1984 book Science Fiction, he praised Fulton's special effects as "deservedly [...] widely praised" noting they "still create a primitive sense of amazement and wonder". While describing the screenplay as "slow-moving" he felt that, "Whale's impish sense of black comedy remains a delight".[30] In Kim Newman and James Marriott's book The Definitive Guide to Horror Movies (2006), Marriott praised the film as "a perfectly judged marriage of menace and comedy, anchored by superlative special effects and a bravura performance from Rains".[78] Newman praised the special effects in the film, declaring that "special effects genius John P. Fulton accomplished with 1930s technology was certainly on a par with anything in 1992's Chevy Chase vehicle Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992)".[79] Newman also praised Rains's role as Griffin, noting the "expressive gestures" as "vital to his performance" and his "terrific voice: velvety with a sly twist, perfect for those wonderful mad scientist speeches".[79] Newman concluded in his five-star review of the film in Empire that "if you set aside Frankenstein as more of a horror film and King Kong (1933) as a fantasy, The Invisible Man is the first truly great American science fiction film".[79]

Retrospective response to the film includes it being listed on several "Best-of" genre lists. In the book The Variety Book of Movie Lists, The Invisible Man is listed among the best films of certain genres by artists in their respective fields. This included directors Joe Dante (Best of Horror), John Carpenter (Best Science Fiction) where he referred to the film as "brilliant", and Ray Harryhausen (Best of Fantasy) where Harryhausen stated that "where do science fiction and so-called horror films begin and fantasy films leave off? Surely they must overlap".[80] In Phil Hardy's Science Fiction (1984), when critics were asked to list the greatest science fiction films of all time, critic Denis Gifford included it in his top ten.[81] In 2008, The Invisible Man was selected for inclusion in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[4][82]

Legacy

editUniversal revived an Invisible Man character for future films but did not attempt to connect the films with any direct storyline as they had done with their films The Mummy or Frankenstein.[38] Examples of these connections include The Invisible Man Returns where the character Geoffrey Radcliffe (Vincent Price) receives the invisibility formula from Dr. Frank Griffin (John Sutton), a relative of Jack Griffin from the first film and Invisible Agent where Frank Raymond is the grandson of Jack Griffin.[83][84] In The Invisible Man's Revenge, the screenplay does not connect Robert Griffin with the previous Griffins who either created, understood, and or operated with the invisibility formula.[85] Universal Pictures first announced the development of The Invisible Man Returns in March 1939, around the time Son of Frankenstein (1939) had been performing decently at the box office.[86] The Invisible Man Returns was distributed theatrically on January 12, 1940.[87] The Invisible Man character shows up in Son of the Invisible Man, one of the episodes of the film Amazon Women on the Moon (1987). The scene is directed by Carl Gottlieb and features Ed Begley, Jr. in an inn similar to the 1933 film where he only thinks he is invisible.[88]

Rains' career benefited greatly from his role in the film, allowing him to become one of Hollywood's most valuable actors. It led him to roles that Newman praised as "everything from The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) (as Bad King John) to Casablanca (1942)".[79] In his 1934 autobiography, Wells only mentioned the film version of The Invisible Man briefly, stating that it was "a tale that, thanks largely to the recent film produced by James Whale, is still read as much as ever it was".[89] Reflecting on her work at Universal, Gloria Stuart described working at the studio as very low quality, noting how ramshackle it was with make-up rooms and wardrobe areas being "very, very primitive" and that apart from the films she made with Whale, she declared all her work at Universal was "terrible" and "real B stuff", noting that the cast and crew working at Universal "considered it slumming".[90]

Reboots

editUnlike other Universal properties, The Invisible Man did not receive any immediate remakes such as those done by Hammer Film Productions.[38]

A remake of The Invisible Man entered development as of February 2016, when Johnny Depp was announced to star in the remake with Ed Solomon writing the film's script, and Alex Kurtzman and Chris Morgan as the producers.[91][92] Kurtzman and Morgan moved on to other projects the following year on November 8.[93] In 2019, Universal began production on the new The Invisible Man that was written and directed by Leigh Whannell and produced by Jason Blum, starring Elisabeth Moss and Oliver Jackson-Cohen as the titular character.[94][95]

When a trailer for the film was released in December the same year, Robert Moran of The Sydney Morning Herald commented that it "met with the kind of confusion that could rattle a filmmaker, not to mention a studio. It seems monster movie fans, long-attuned to the bandage-wrapped antics of The Invisible Man of yore, weren't expecting Whannell's allegory on domestic violence trauma".[96] Whannell commented on his change from the norm on the style, explaining that he knew there was going to be some backlash against the film as he was "modernizing it and centering it not around the Invisible Man but his victim".[97] Whannel compared his The Invisible Man film to the popular image of the character: "The iconic image of the Invisible Man is one of a floating pair of sunglasses, you know? I knew I had to move it away from that".[97] Whannell's The Invisible Man was released on February 28, 2020.[97]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Nourmand & Marsh 2003, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 78.

- ^ a b "The Invisible Man". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "2008 Entries to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. December 30, 2008. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 198.

- ^ Mank 2013, 147; 198.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Mank 2013, 214.

- ^ Mank 2013, 214; 228.

- ^ Mank 2013, 235.

- ^ Mank 2013, 235; 251.

- ^ a b c d e Mank 2013, 264.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 281.

- ^ Mank 2013, 281; 298.

- ^ Mank 2013, 298.

- ^ Mank 2013, 313.

- ^ Mank 2013, 313; 331.

- ^ a b c Mank 2013, 329.

- ^ Mank 2013, 415.

- ^ Mank 2013, 467; 476.

- ^ Mank 2013, 476.

- ^ Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 491.

- ^ Mank 2013, 491; 507.

- ^ Mank 2013, 507.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 538.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 555.

- ^ Mank 2013, 538; 572.

- ^ a b Vieira 2003, p. 55.

- ^ a b Hardy 1984, p. 89.

- ^ Clarens 1997, p. 205.

- ^ Mank 2013, 581; 596.

- ^ Mank 2013, 147.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 607.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 682.

- ^ Mank 2013, 949.

- ^ Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b c d e f Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Mank 2013, 682; 755.

- ^ Mank 2013, 819.

- ^ Mank 2013, 934.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1047.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1538.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 1548.

- ^ a b c Mank 2013, 1057.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 1618.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 81.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1009.

- ^ Benson 1985, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Fulton 1934, pp. 200–201, 214.

- ^ Fulton, John P. "How We Made 'The Invisible Man.'" American Cinematographer 15:5 (September 1934), 201.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 974.

- ^ Fulton, John P. "How We Made 'The Invisible Man.'" American Cinematographer 15:5 (September 1934), 202.

- ^ Nourmand & Marsh 2004, p. 132.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1057; 1072.

- ^ ""Invisible Man" To Be at the Kiva as Hallowee'en Picture". Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado. October 31, 1933. p. 2. Retrieved February 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1370.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 1072.

- ^ a b c Mank 2013, 1088.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1198.

- ^ The Invisible Man (Classic Monster Collection) [VHS]. ASIN 6300185281.

- ^ Arrington 2000.

- ^ a b c "The Invisible Man (1933)". AllMovie. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Erickson 2005.

- ^ a b Mank 2013, 1354.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1348.

- ^ Shaffer 2012.

- ^ Vorel, Jim (August 3, 2021). "The Universal Monsters Are Creeping to 4K UHD for the First Time". Paste. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Hall 1933.

- ^ Char. 1933, p. 14.

- ^ Char. 1933, p. 20.

- ^ "The Invisible Man". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folkm Inc.: 4 November 18, 1933.

- ^ Mosher 1936, p. 69.

- ^ Mank 1989, p. 312.

- ^ a b Clarens 1997, p. 66.

- ^ Sullivan 1986, pp. 457, 460.

- ^ Marriott & Newman 2018, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Newman 2000.

- ^ Beck 1994, pp. 58, 81, 97.

- ^ Hardy 1984, p. 389.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Invisible Agent". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Hanke 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Hanke 2014, p. 120.

- ^ Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 208.

- ^ Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 207.

- ^ Mank 2013, 1214.

- ^ Wykes 1977, p. 13.

- ^ Weaver 1994, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Kit 2016.

- ^ Fleming 2016.

- ^ Kit & Couch 2017.

- ^ Kroll 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro 2019.

- ^ Moran 2020.

- ^ a b c Hipes 2019.

Sources

edit- Arrington, Chuck (November 7, 2000). "The Invisible Man-1933". DVD Talk. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Beck, J. Spencer, ed. (1994). The Variety Book of Movie Lists. Hamlyn. ISBN 0600580415.

- Benson, Michael (1985). Vintage Science Fiction Films, 1896-1949. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-89950-085-4.

- Char. (November 21, 1933). "The Invisible Man". Variety. Vol. 112, no. 11. Retrieved February 25, 2021.'

- Clarens, Carlos (1997) [1st pub. 1967]. An Illustrated History of Horror and Science-Fiction Films. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80800-5.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (May 10, 2019). "Universal-Blumhouse's 'The Invisible Man' Adds 'A Wrinkle In Time' Star Storm Reid". Deadline. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- Erickson, Glenn (January 12, 2005). "The Invisible Man - The Legacy Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 9, 2016). "Johnny Depp To Star In 'The Invisible Man' At Universal". Deadline. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016.

- Fulton, John P. (September 1934). "How We Made The Invisible Man". American Cinematographer.

- Hall, Mordaunt (November 18, 1933). "Movie Review - The Invisible Man". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- Hanke, Ken (2014) [1991]. A Critical Guide to Horror Film Series. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72642-9.

- Hardy, Phil, ed. (1984). Science Fiction. Morrow. ISBN 0688008429.

- Hipes, Patrick (August 22, 2019). "Blumhouse's 'The Invisible Man' Will Emerge Two Weeks Earlier – Update". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Kit, Borys; Couch, Aaron (November 8, 2017). "Universal's "Monsterverse" in Peril as Top Producers Exit (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Kit, Borys (February 9, 2016). "Johnny Depp to Star in Universal's 'Invisible Man' Reboot". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016.

- Kroll, Justin (January 24, 2019). "'Invisible Man' Finds Director, Sets New Course for Universal's Monster Legacy (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- Mank, Gregory W. (1989). The Hollywood Hissables. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810821346.

- Mank, Gregory Wm. (2013). Riley, Philip J. (ed.). The Invisible Man (Kindle ed.). BearManor Media.

- Marriott, James; Newman, Kim (2018) [1st pub. 2006]. The Definitive Guide to Horror Movies. London: Carlton Books. ISBN 9781787391390.

- Moran, Robert (January 31, 2020). "Leigh Whannell's The Invisible Man is an allegory about gaslighting". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- Mosher, John (May 23, 1936). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corp.

- Mosher, John (August 28, 1937). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corp.

- Newman, Kim (January 2000). "The Invisible Man Review". Empire. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Nourmand, Tony; Marsh, Graham, eds. (2003). Science Fiction Poster Art. London: Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-85410-946-4.

- Nourmand, Tony; Marsh, Graham, eds. (2004). Horror Poster Art. London: Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-84513-010-3.

- Shaffer, RL (June 28, 2012). "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection Blu-ray". IGN. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Sullivan, ed. (1986). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. Viking Penguin Inc. ISBN 0-670-80902-0.

- Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror from Gothic to Cosmic. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0810945355.

- Weaver, Tom (September 1994). "Dark Houses and Invisible Men". Fangoria. Vol. 13.

- Weaver, Tom; Brunas, Michael; Brunas, John (2007) [1990]. Universal Horrors (2 ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2974-5.

- Williams, Keith (2007). H. G. Wells, Modernity and the Movies. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-059-1.

- Wykes, Alan (1977). H. G. Wells in the Cinema. Jupiter Books. ISBN 0904041174.

External links

edit- Quotations related to The Invisible Man (film) at Wikiquote

- Media related to The Invisible Man (film) at Wikimedia Commons

- The Invisible Man at IMDb

- The Invisible Man at Metacritic

- The Invisible Man at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Invisible Man at the TCM Movie Database

- The Invisible Man at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films