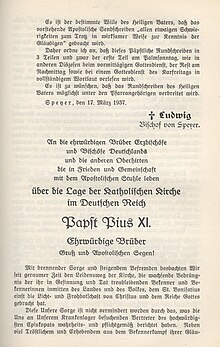

Mit brennender Sorge (ⓘ German pronunciation: [mɪt ˈbʀɛnəndɐ ˈzɔʁɡə], in English "With deep [lit. 'burning'] anxiety") is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March).[1] Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was smuggled into Germany for fear of censorship and was read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches on one of the Church's busiest Sundays, Palm Sunday (21 March that year).[2][3]

| Mit brennender Sorge German for 'With deep [lit. "burning"] anxiety' Encyclical of Pope Pius XI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature date | 14 March 1937 |

| Subject | On the Church and the German Reich |

| Number | 28 of 31 of the pontificate |

| Text | |

The encyclical condemned breaches of the 1933 Reichskonkordat agreement signed between the German Reich and the Holy See.[4] It condemned "pantheistic confusion", "neopaganism", "the so-called myth of race and blood", and the idolizing of the State. It contained a vigorous defense of the Old Testament with the belief that it prepares the way for the New.[5] The encyclical states that race is a fundamental value of the human community, which is necessary and honorable but condemns the exaltation of race, or the people, or the state, above their standard value to an idolatrous level.[6] The encyclical declares "that man as a person possesses rights he holds from God, and which any collectivity must protect against denial, suppression or neglect."[7] National Socialism, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party are not named in the document. The term Reichsregierung is used to refer to the German government.[8]

The effort to produce and distribute over 300,000 copies of the letter was entirely secret, allowing priests across Germany to read the letter without interference.[9] The Gestapo raided the churches the next day to confiscate all the copies they could find, and the presses that had printed the letter were closed. According to historian Ian Kershaw, an intensification of the general anti-church struggle began around April in response to the encyclical.[10] Klaus Scholder wrote: "state officials and the Party reacted with anger and disapproval. Nevertheless the great reprisal that was feared did not come. The concordat remained in force and despite everything the intensification of the battle against the two churches which then began remained within ordinary limits."[11] The regime further constrained the actions of the Church and harassed monks with staged prosecutions for alleged immorality and phony abuse trials.[12] Though Hitler is not named in the encyclical, the German text does refer to a "Wahnprophet", which some have interpreted as meaning "mad prophet" and as referring to Hitler himself.[13]

Background

editFollowing the Nazi takeover, the Catholic Church hierarchy in Germany initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, but by 1937 had become highly disillusioned. A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church followed the Nazi takeover.[14] Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism. Two thousand functionaries of the Bavarian People's Party were rounded up by police in late June 1933. They along with the national Catholic Centre Party, ceased to exist in early July, as the Nazi Party became the only legally permitted party in the country. Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen meanwhile negotiated the Reichskonkordat treaty with the Vatican, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[15] Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".[16]

The Reichskonkordat (English: Reich Concordat) was signed on 20 July 1933 between the Holy See and Germany. According to historian Pinchas Lapide, the Nazis saw the treaty as giving them moral legitimacy and prestige, whilst the Catholic Church sought to protect itself from persecution through a signed agreement.[17] According to Guenter Lewy, a common view within Church circles at the time was that Nazism would not last long, and the favorable Concordat terms would outlive the current regime (the Concordat does remain in force today).[18] A Church handbook published with the recommendation of the entire German Church episcopate described the Concordat as "proof that two powers, totalitarian in their character, can find an agreement, if their domains are separate and if overlaps in jurisdiction become parallel or in a friendly manner lead them to make common cause".[19] Lewy wrote "The harmonious co-operation anticipated at the time did not quite materialize" but that the reasons for this "lay less in the lack of readiness of the Church than in the short sighted policies of the Hitler regime."[19]

In Mit brennender Sorge, Pope Pius XI said that the Holy See had signed the Concordat "in spite of many serious misgivings" and in the hope it might "safeguard the liberty of the church in her mission of salvation in Germany". The treaty comprised 34 articles and a supplementary protocol. Article 1 guaranteed "freedom of profession and public practice of the Catholic religion" and acknowledged the right of the church to regulate its own affairs. Within three months of the signing of the document, Cardinal Bertram, head of the German Catholic Bishops Conference, was writing in a pastoral letter of "grievous and gnawing anxiety" with regard to the government's actions towards Catholic organisations, charitable institutions, youth groups, press, Catholic Action, and the mistreatment of Catholics for their political beliefs.[20] According to Paul O'Shea, Hitler had a "blatant disregard" for the Concordat, and its signing was to him merely a first step in the "gradual suppression of the Catholic Church in Germany".[21] Anton Gill wrote that "with his usual irresistible, bullying technique, Hitler then proceeded to take a mile where he had been given an inch" and closed all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:

It quickly became clear that [Hitler] intended to imprison the Catholics, as it were, in their own churches. They could celebrate mass and retain their rituals as much as they liked, but they could have nothing at all to do with German society otherwise. Catholic schools and newspapers were closed, and a propaganda campaign against the Catholics was launched.[22]

Following the signing of the document, the formerly outspoken nature of opposition by German Catholic leaders towards the Nazi movement weakened considerably.[23] But violations of the Concordat by the Nazis began almost immediately and were to continue such that Falconi described the Concordat with Germany as "a complete failure".[24] The Concordat, wrote William Shirer, "was hardly put to paper before it was being broken by the Nazi Government". The Nazis had promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church, on 14 July. On 30 July, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders were to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped-up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[25] Historian of the German Resistance Peter Hoffmann wrote that, following the Nazi takeover:

[The Catholic Church] could not silently accept the general persecution, regimentation or oppression, nor in particular the sterilization law of summer 1933. Over the years until the outbreak of war Catholic resistance stiffened until finally its most eminent spokesman was the Pope himself with his encyclical Mit brennender Sorge … of 14 March 1937, read from all German Catholic pulpits … In general terms, therefore, the churches were the only major organisations to offer comparatively early and open resistance: they remained so in later years.[26]

In August 1936 The German episcopate had asked Pius XI for an encyclical that would deal with the current situation of the Church in Germany.[27] In November 1936 Hitler had a meeting with Cardinal Faulhaber during which he indicated that more pressure would be put on the Church unless it collaborated more zealously with the regime.[28] On 21 December 1936 the Pope invited, via Cardinal Pacelli, senior members of the German episcopate to Rome. On 16 January 1937 five German prelates and Cardinal Pacelli agreed unanimously that the time had now come for public action by the Holy See.[28] Pope Pius XI was gravely ill but he too was convinced of the need to publish an encyclical about the Church in Germany as soon as possible.[29]

Authorship

editA five-member commission drafted the encyclical. According to Paul O'Shea the carefully worded denunciation of aspects of Nazism was formulated between 16 and 21 January 1937, by Pius XI, Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII) and German cardinals Bertram, Faulhaber and Schulte, and Bishops Preysing and Galen.[30] Cardinal Bertram of Breslau was the chairman of the German Conference of Bishops, and after the Nazi takeover he had favoured a non-confrontational approach toward the government and developed a protest system which "satisfied the demands of the other bishops without annoying the regime".[31] Berlin's Bishop Konrad von Preysing had been one of the most consistent and outspoken critics of the Nazi regime to emerge from the German Church hierarchy.[32][33] Munich's Archbishop Michael von Faulhaber had been a staunch defender of Catholic rights.[34] The conservative Bishop of Münster, Count Galen, would later distinguish himself by leading the Church's protest against Nazi euthanasia.[35]

Cardinal Faulhaber's draft of the encyclical, consisting of eleven large single sheets and written in his own hand, was presented to Vatican Secretary of State Pacelli on 21 January.[29] Falconi said that the encyclical "was not so much an amplification of Faulhaber's draft as a faithful and even literal transcription of it" while "Cardinal Pacelli, at Pius XI's request, merely added a full historical introduction on the background of the Concordat with the Third Reich."[29] According to John-Peter Pham, Pius XI credited the encyclical to Cardinal Pacelli.[36] According to historian Frank J. Coppa, Cardinal Pacelli wrote a draft that the Pope thought was too weak and unfocused and therefore substituted a more critical analysis.[37] Pacelli described the encyclical as "a compromise" between the Holy See's sense that it could not be silent set against "its fears and worries".[37]

According to Dr. Robert A. Ventresca, professor at King's University College at the University of Western Ontario, Cardinal Faulhaber, who wrote a first draft, was adamant that the encyclical should be careful in both its tone and substance and should avoid explicit reference to Nazism or the Nazi Party.[38] Historian William Shirer wrote that the document accused the regime of sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church".[25] According to Historian Klaus Scholder, the leader of the German Bishops conference, Cardinal Bertram, sought to blunt the impact of the encyclical by ordering that critical passages should not be read aloud. He took the view that "introductory thoughts about the failure of the Reich government to observe the treaty are meant more for the leaders, not for the great mass of believers."[39]

Content

editThe numbers conform to the numbers used by the Vatican in its English translation of the text.

Violations of the Concordat

editIn the introduction and sections 1–8 of the encyclical Pius XI wrote of his "deep anxiety and growing surprise" on observing the travails of the Catholic Church in Germany with the terms of Concordat being openly broken and the faithful being oppressed as had never been seen before.[40]

1. It is with deep anxiety and growing surprise that We have long been following the painful trials of the Church and the increasing vexations which afflict those who have remained loyal in heart and action in the midst of a people that once received from St. Boniface the bright message and the Gospel of Christ and God's Kingdom.[41]

3. … Hence, despite many and grave misgivings, We then decided not to withhold Our consent [to the Concordat] for We wished to spare the Faithful of Germany, as far as it was humanly possible, the trials and difficulties they would have had to face, given the circumstances, had the negotiations fallen through[41]

4. … The experiences of these last years have fixed responsibilities and laid bare intrigues, which from the outset only aimed at a war of extermination. In the furrows, where We tried to sow the seed of a sincere peace, other men – the "enemy" of Holy Scripture – oversowed the cockle of distrust, unrest, hatred, defamation, of a determined hostility overt or veiled, fed from many sources and wielding many tools, against Christ and His Church. They, and they alone with their accomplices, silent or vociferous, are today responsible, should the storm of religious war, instead of the rainbow of peace, blacken the German skies.[41]

5. At the same time, anyone must acknowledge, not without surprise and reprobation, how the other contracting party emasculated the terms of the treaty, distorted their meaning, and eventually considered its more or less official violation as a normal policy … Even now that a campaign against the confessional schools, which are guaranteed by the concordat, and the destruction of free election, where Catholics have a right to their children's Catholic education, afford evidence, in a matter so essential to the life of the Church, of the extreme gravity of the situation.[41]

Race

editPius then affirmed the articles of faith that Nazi ideology was attacking. He stated that true belief in God could not be reconciled with race, people or state raised beyond their standard value to idolatrous levels.[42] National religion or a national God was rejected as a grave error and that the Christian God could not be restricted "within the frontiers of a single people, within the pedigree of one single race." (sections 9–13).[42] Historian Michael Phayer wrote:

In Divini Redemptoris, he [Pius XI] condemned communism once again, while in Mit brennender Sorge he criticized racism in carefully measured words. As Peter Godman has pointed out, this was a political decision that ignored the immorality of Nazi racism as it had been discerned by in-house committees at the Vatican. … the encyclical stepped lightly around the issue of racism so as to keep the Concordat intact.[43]

Martin Rhonheimer writes that while Mit brennender Sorge asserts "race" is a "fundamental value of the human community", "necessary and honorable", it condemns the "exaltation of race, or the people, or the state, or a particular form of state", "above their standard value" to "an idolatrous level".[44] According to Rhonheimer, it was Pacelli who added to Faulhaber's milder draft the following passage (8):[45]

7. … Whoever identifies, by pantheistic confusion, God and the universe, by either lowering God to the dimensions of the world, or raising the world to the dimensions of God, is not a believer in God. Whoever follows that so-called pre-Christian Germanic conception of substituting a dark and impersonal destiny for the personal God, denies thereby the Wisdom and Providence of God.[41]

8. Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State, or a particular form of State, or the depositories of power, or any other fundamental value of the human community – however necessary and honorable be their function in worldly things – whoever raises these notions above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level, distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God; he is far from the true faith in God and from the concept of life which that faith upholds.[41]

Against this background to the encyclical, Faulhaber suggested in an internal Church memorandum that the bishops should inform the Nazi regime

…that the Church, through the application of its marriage laws, has made and continues to make, an important contribution to the state's policy of racial purity; and is thus performing a valuable service for the regime's population policy.[45]

Vidmar wrote that the encyclical condemned particularly the purported paganism of the national socialist ideology, the myth of race and blood, and the fallacy of its conception of God. It warned Catholics that the growing Nazi ideology, which exalted one race over all others, was incompatible with Catholic Christianity.[46]

11. None but superficial minds could stumble into concepts of a national God, of a national religion; or attempt to lock within the frontiers of a single people, within the narrow limits of a single race, God, the Creator of the universe, King and Legislator of all nations before whose immensity they are "as a drop of a bucket"[41]

Historian Garry Wills, in the context of Jews having traditionally been described as deicides, says that the encyclical affirms "'Jesus received his human nature from a people who crucified him' – not some Jews, but the Jewish people" and that it was also Pius XI who had disbanded the Catholic organization "Friends of Israel" that had campaigned to have the charge of deicide dropped.[47] The charge of deicide against all Jewish people was later dropped during the Second Vatican Council.[citation needed]

Defending the Old Testament

editHistorian Paul O'Shea says the encyclical contains a vigorous defense of the Old Testament out of belief that it prepared the way for the New.[5]

15. The sacred books of the Old Testament are exclusively the word of God, and constitute a substantial part of his revelation; they are penetrated by a subdued light, harmonizing with the slow development of revelation, the dawn of the bright day of the redemption. As should be expected in historical and didactic books, they reflect in many particulars the imperfection, the weakness and sinfulness of man … Nothing but ignorance and pride could blind one to the treasures hoarded in the Old Testament.[41]

16. Whoever wishes to see banished from church and school the Biblical history and the wise doctrines of the Old Testament, blasphemes the name of God, blasphemes the Almighty's plan of salvation[41]

Claimed attacks on Hitler

editThere is no mention of Hitler by name in the encyclical but some works say that Hitler is described as a "mad prophet" in the text. Anthony Rhodes was a novelist, travel writer, biographer and memoirist and convert to Roman Catholicism.[48] He was encouraged by a Papal nuncio to write books on modern Church history and he was later awarded a Papal knighthood.[49] In one of his books (The Vatican in the Age of the Dictators) he wrote of the encyclical "Nor was the Führer himself spared, for his 'aspirations to divinity', 'placing himself on the same level as Christ'; 'a mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance".[50] This has subsequently been cited in works which repeat Rhodes saying that Hitler is described as a "mad prophet" in the encyclical.[51]

Historian John Connelly writes:

Some accounts exaggerate the directness of the pope's criticism of Hitler. Contrary to what Anthony Rhodes in The Vatican in the Age of the Dictators writes, there were oblique references to Hitler. It was not the case that Pius failed to "spare the Führer," or called him a "mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance." The text limits its critique of arrogance to unnamed Nazi "reformers".[52]

Historian Michael Phayer wrote that the encyclical does not condemn Hitler or National Socialism, "as some have erroneously asserted".[53] Historian Michael Burleigh sees the passage as pinpointing "the tendency of the Führer-cult to elevate a man into god."

The relevant passage in the English version of the encyclical is:

17. … Should any man dare, in sacrilegious disregard of the essential differences between God and His creature, between the God-man and the children of man, to place a mortal, were he the greatest of all times, by the side of, or over, or against, Christ, he would deserve to be called prophet of nothingness, to whom the terrifying words of Scripture would be applicable: "He that dwelleth in heaven shall laugh at them" (Psalms ii. 3).[54]

(The German text uses the term "ein Wahnprophet", in which the component Wahn can mean "illusion" or "delusion", while the Italian text uses "un profeta di chimere" (a prophet of chimeras; that is, a prophet as the product of the imagination).)

Historian Susan Zuccotti sees the above passage as an unmistakable jibe at Hitler.[55]

Fidelity to the Church and Bishop of Rome

editPius then went on to assert that people were obliged to believe in Christ, divine revelation, and the primacy of the Bishop of Rome (Sections 14–24).[42]

18. Faith in Christ cannot maintain itself pure and unalloyed without the support of faith in the Church … Whoever tampers with that unity and that indivisibility wrenches from the Spouse of Christ one of the diadems with which God Himself crowned her; he subjects a divine structure, which stands on eternal foundations, to criticism and transformation by architects whom the Father of Heaven never authorized to interfere.[41]

21. In your country, Venerable Brethren, voices are swelling into a chorus urging people to leave the Church, and among the leaders there is more than one whose official position is intended to create the impression that this infidelity to Christ the King constitutes a signal and meritorious act of loyalty to the modern State. Secret and open measures of intimidation, the threat of economic and civic disabilities, bear on the loyalty of certain classes of Catholic functionaries, a pressure which violates every human right and dignity …[41]

22. Faith in the Church cannot stand pure and true without the support of faith in the primacy of the Bishop of Rome. The same moment when Peter, in the presence of all the Apostles and disciples, confesses his faith in Christ, Son of the Living God, the answer he received in reward for his faith and his confession was the word that built the Church, the only Church of Christ, on the rock of Peter (Matt. xvi. 18) … [41]

Soteriology

editHistorian Michael Burleigh views the following passage as a rejection of the Nazis' conception of collective racial immortality:[56]

24. "Immortality" in a Christian sense means the survival of man after his terrestrial death, for the purpose of eternal reward or punishment. Whoever only means by the term, the collective survival here on earth of his people for an indefinite length of time, distorts one of the fundamental notions of the Christian Faith and tampers with the very foundations of the religious concept of the universe, which requires a moral order. [Whoever does not wish to be a Christian ought at least to renounce the desire to enrich the vocabulary of his unbelief with the heritage of Christian ideas.]

The bracketed text is in Burleigh's book but not on the Vatican's web site English version of the Encyclical as of December 2014; German version has it in section 29. (Wenn er nicht Christ sein will, sollte er wenigstens darauf verzichten, den Wortschatz seines Unglaubens aus christlichem Begriffsgut zu bereichern.)

Nazi philosophy

editThe Nazi principle that "Right is what is advantageous to the people" was rejected on the basis that what was illicit morally could not be to the advantage of the people.[42] Human laws which opposed natural law were described as not "obligatory in conscience". The rights of parents in the education of their children are defended under natural law and the "notorious coercion" of Catholic children into interdenominational schools are described as "void of all legality" (sections 33–37).[42] Pius ends the encyclical with a call to priests and religious to serve truth, unmask and refute error, with the laity being urged to remain faithful to Christ and to defend the rights which the Concordat had guaranteed them and the Church.[42] The encyclical dismisses "[Nazi] attempts to dress up their ghastly doctrines in the language of religious belief.":[56] Burleigh also mentions the encyclical's rejection of Nazi contempt for Christian emphasis on suffering and that, through the examples of martyrs, the Church needed no lessons on heroism from people who obsessed on greatness, strength and heroism.[57]

Compatibility of humility and heroism

edit27. Humility in the spirit of the Gospel and prayer for the assistance of grace are perfectly compatible with self-confidence and heroism. The Church of Christ, which throughout the ages and to the present day numbers more confessors and voluntary martyrs than any other moral collectivity, needs lessons from no one in heroism of feeling and action. The odious pride of reformers only covers itself with ridicule when it rails at Christian humility as though it were but a cowardly pose of self-degradation.

Christian grace contrasted with natural gifts

edit28. "Grace," in a wide sense, may stand for any of the Creator's gifts to His creature; but in its Christian designation, it means all the supernatural tokens of God's love... To discard this gratuitous and free elevation in the name of a so-called German type amounts to repudiating openly a fundamental truth of Christianity. It would be an abuse of our religious vocabulary to place on the same level supernatural grace and natural gifts. Pastors and guardians of the people of God will do well to resist this plunder of sacred things and this confusion of ideas.

Defense of natural law

editBurleigh views the encyclical as confounding the Nazi philosophy that "Right is what is advantageous to the people" through its defense of Natural Law:[57]

29. … To hand over the moral law to man's subjective opinion, which changes with the times, instead of anchoring it in the holy will of the eternal God and His commandments, is to open wide every door to the forces of destruction. The resulting dereliction of the eternal principles of an objective morality, which educates conscience and ennobles every department and organization of life, is a sin against the destiny of a nation, a sin whose bitter fruit will poison future generations.[41]

In his history of the German Resistance, Anton Gill interprets the encyclical as having asserted the "inviolability of human rights".[2] Historian Emma Fattorini wrote that the Pope's

indignation was obviously not addressed at improbable democratic-liberal human rights issues, nor was there a generic and abstract appeal to evangelical principles. It was rather the Church's competition with the totalitarian regression of the concept of Volk that in the Nazi state-worship totally absorbed the community-people relationship[58]

30. … Human laws in flagrant contradiction with the natural law are vitiated with a taint which no force, no power can mend. In the light of this principle one must judge the axiom, that "right is common utility," a proposition which may be given a correct significance, it means that what is morally indefensible, can never contribute to the good of the people. But ancient paganism acknowledged that the axiom, to be entirely true, must be reversed and be made to say: "Nothing can be useful, if it is not at the same time morally good" (Cicero, De Off. ii. 30). Emancipated from this oral rule, the principle would in international law carry a perpetual state of war between nations; for it ignores in national life, by confusion of right and utility, the basic fact that man as a person possesses rights he holds from God, and which any collectivity must protect against denial, suppression or neglect.[41]

Thomas Banchoff considers this the first explicit mention of human rights by a Pope, something the Pope would affirm the following year in a little-noticed letter to the American Church. Banchoff writes: "the church's full embrace of the human rights agenda would have to wait until the 1960s".[59]

Defense of Catholic schooling

editThe encyclical also defends Catholic schooling against Nazi attempts to monopolize education.[60]

31. The believer has an absolute right to profess his Faith and live according to its dictates. Laws which impede this profession and practice of Faith are against natural law. Parents who are earnest and conscious of their educative duties, have a primary right to the education of the children God has given them in the spirit of their Faith, and according to its prescriptions. Laws and measures which in school questions fail to respect this freedom of the parents go against natural law, and are immoral.

33. … Many of you, clinging to your Faith and to your Church, as a result of your affiliation with religious associations guaranteed by the concordat, have often to face the tragic trial of seeing your loyalty to your country misunderstood, suspected, or even denied, and of being hurt in your professional and social life … Today, as We see you threatened with new dangers and new molestations, We say to you: If any one should preach to you a Gospel other than the one you received on the knees of a pious mother, from the lips of a believing father, or through teaching faithful to God and His Church, "let him be anathema" (Gal. i. 9).[41]

34. No one would think of preventing young Germans establishing a true ethnical community in a noble love of freedom and loyalty to their country. What We object to is the voluntary and systematic antagonism raised between national education and religious duty. That is why we tell the young: Sing your hymns to freedom, but do not forget the freedom of the children of God. Do not drag the nobility of that freedom in the mud of sin and sensuality …[41]

Call to priests and religious

edit36. …The priest's first loving gift to his neighbors is to serve truth and refute error in any of its forms. Failure on this score would be not only a betrayal of God and your vocation, but also an offense against the real welfare of your people and country. To all those who have kept their promised fidelity to their Bishops on the day of their ordination; to all those who in the exercise of their priestly function are called upon to suffer persecution; to all those imprisoned in jail and concentration camps, the Father of the Christian world sends his words of gratitude and commendation.[41]

37. Our paternal gratitude also goes out to Religious and nuns, as well as Our sympathy for so many who, as a result of administrative measures hostile to Religious Orders, have been wrenched from the work of their vocation. If some have fallen and shown themselves unworthy of their vocation, their fault, which the Church punishes, in no way detracts from the merit of the immense majority, who, in voluntary abnegation and poverty, have tried to serve their God and their country …[41]

Call to parents

edit39. We address Our special greetings to the Catholic parents. Their rights and duties as educators, conferred on them by God, are at present the stake of a campaign pregnant with consequences. The Church cannot wait to deplore the devastation of its altars, the destruction of its temples, if an education, hostile to Christ, is to profane the temple of the child's soul consecrated by baptism, and extinguish the eternal light of the faith in Christ for the sake of counterfeit light alien to the Cross …[41]

Moderation of the encyclical but with warnings

edit41. We have weighed every word of this letter in the balance of truth and love. We wished neither to be an accomplice to equivocation by an untimely silence, nor by excessive severity to harden the hearts of those who live under Our pastoral responsibility; …[41]

42. …Then We are sure, the enemies of the Church, who think that their time has come, will see that their joy was premature, and that they may close the grave they had dug. The day will come when the Te Deum of liberation will succeed to the premature hymns of the enemies of Christ: Te Deum of triumph and joy and gratitude, as the German people return to religion, bend the knee before Christ, and arming themselves against the enemies of God, again resume the task God has laid upon them.[41]

43. He who searches the hearts and reins (Psalm vii. 10) is Our witness that We have no greater desire than to see in Germany the restoration of a true peace between Church and State. But if, without any fault of Ours, this peace is not to come, then the Church of God will defend her rights and her freedom in the name of the Almighty whose arm has not shortened …[41]

Release

editThe encyclical was written in German and not the usual Latin of official Catholic Church documents. Because of government restrictions, the nuncio in Berlin, Archbishop Cesare Orsenigo, had the encyclical distributed by courier. There was no pre-announcement of the encyclical, and its distribution was kept secret in an attempt to ensure the unhindered public reading of its contents in all the Catholic churches of Germany.[61] Printers close to the church offered their services and produced an estimated 300,000 copies, which was still insufficient. Additional copies were created by hand and using typewriters. After its clandestine distribution, the document was hidden by many congregations in their tabernacles for protection. It was read from the pulpits of German Catholic parishes on Palm Sunday 1937.[62]

Nazi response

editThe release of Mit brennender Sorge precipitated an intensification of the Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany.[63] Hitler was infuriated.[2] Twelve printing presses were seized, and hundreds of people sent either to prison or the concentration camps.[2] In his diary, Goebbels wrote that there were heightened verbal attacks on the clergy from Hitler, and wrote that Hitler had approved the start of trumped up "immorality trials" against clergy and anti-Church propaganda campaign. Goebbels' orchestrated attack included a staged "morality trial" of 37 Franciscans.[64] On the "Church Question", wrote Goebbels, "after the war it has to be generally solved … There is, namely, an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view".[64]

The Catholic Herald's German correspondent wrote almost four weeks after the issuing of the encyclical that:

Hitler has not yet decided what to do. Some of his counsellors try to persuade him to declare the Concordat as null and void. Others reply that that would do immense damage to Germany's prestige in the world, particularly to its relations with Austria and to its influence in Nationalist Spain. Moderation and prudence are advocated by them. There is, unfortunately, no hope that the German Reich will come back to a full respect of its Concordat obligations and that the Nazis will give up those of their doctrines which have been condemned by the Pope in the new Encyclical. But it is well possible that a definite denunciation of the Concordat and a rupture of diplomatic relations between Berlin and the Holy See will be avoided, at least for the time being.[65]

The Catholic Herald reported on 23 April:

It is understood that the Vatican will reply to the note of complaint presented to it by the German Government in regard to the Encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge. The note was not a defence of Nazism, but a criticism of the Vatican's action at a time when negotiations on the relations between the Vatican and Germany were still in being. It would seem that the Vatican, desirous of finding a modus vivendi, however slight the chance of it may appear, wishes to clear up any possible misunderstanding. On 15 April Cardinal Pacelli received Herr von Bergen, the Reich Ambassador at the Holy See. This was the first diplomatic meeting since the publication of the Encyclical.[66]

The Tablet reported on 24 April 1937:

The case in the Berlin court against three priests and five Catholic laymen is, in public opinion, the Reich's answer to the Pope's Mit brennender Sorge encyclical, as the prisoners have been in concentration camps for over a year. Chaplain Rossaint, of Dusseldorf; is, however, known as a pacifist and an opponent of the National Socialist regime, and it is not denied that he was indiscreet; but he is, moreover, accused of having tried to form a Catholic-Communist front on the plea that he baptized a Jewish Communist. This the accused denies, and his defence has been supported by Communist witnesses.[67]

The (censored) German newspapers made no mention of the encyclical. The Gestapo visited the offices of every German diocese the next day and seized all the copies they could find.[61] Every publishing company that had printed it was closed and sealed, diocesan newspapers were proscribed, and limits imposed on the paper available for Church purposes.

The true extent of the Nazi fury at this encyclical was shown by the immediate measures taken in Germany to counter further propagation of the document. Not a word of it was printed in newspapers, and the following day the Secret Police visited the diocesan offices and confiscated every copy they could lay their hands on. All the presses which had printed it were closed and sealed. The bishops' diocesan magazines (Amtsblatter) were proscribed; and paper for church pamphlets or secretarial work was severely restricted. A host of other measures, such as diminishing the State grants to theology students and needy priests (agreed in the Concordat) were introduced. And then a number of futile, vindictive measures which did little to harm the Church …[68]

According to Carlo Falconi: "The pontifical letter still remains the first great official public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism, and the Pope's courage astonished the world."[69]

Historian Frank J. Coppa wrote that the encyclical was viewed by the Nazis as "a call to battle against the Reich" and that Hitler was furious and "vowed revenge against the Church".[37]

Klaus Scholder wrote:[70]

Whereas the reading of the encyclical was widely felt in German Catholicism to be a liberation, state officials and the Party reacted with anger and disapproval. Nevertheless the great reprisal that was feared did not come. The concordat remained in force and despite everything the intensification of the battle against the two churches which then began remained within ordinary limits.

According to John Vidmar, Nazi reprisals against the Church in Germany followed thereafter, including "staged prosecutions of monks for homosexuality, with the maximum of publicity".[71] One hundred and seventy Franciscans were arrested in Koblenz and tried for "corrupting youth" in a secret trial, with numerous allegations of priestly debauchery appearing in the Nazi-controlled press, while a film produced for the Hitler Youth showed men dressed as priests dancing in a brothel.[72] The Catholic Herald reported on 15 October 1937:

The failure of the Nazi "morality" trials campaign against the Church can be gauged from the fact that, up to the beginning of August, the Courts were only able to condemn 74 religious and secular priests on such charges. The total number of religious and secular priests in Germany, according to the Catholic paper Der Deutsche Weg, is 122,792. The justice of such condemnations as the Nazis were able to obtain is more than suspect.[73]

A pastoral letter issued by the German bishops in 1938 says "Currency and morality trials are put up in such a way which shows that not justice but anti-Catholic propaganda is the main concern".[74]

Catholic response

editIan Kershaw wrote that during the Nazi period, the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of; … especially of the Catholic Church – against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.[75] Anton Gill wrote that, in 1937, amidst the harassment of the church and following the hundreds of arrests and closure of Catholic presses that followed the issuing of Mit brennender Sorge, at least 800,000 people attended a pilgrimage centred on Aachen – a massive demonstration by the standards of the day – and some 60,000 attended the 700th anniversary of the bishopric of Franconia – about equal to the city's entire population.[2]

The Vatican's Secretary of State, Cardinal Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII), wrote to Germany's Cardinal Faulhaber on 2 April 1937 explaining that the encyclical was theologically and pastorally necessary "to preserve the True Faith in Germany." The encyclical also defended baptized Jews, still considered to be Jews by the Nazis because of racial theories that the Church could not and would not accept. Although the encyclical does not specifically mention the Jewish people,[76] it condemns the exaltation of one race or blood over another, i.e. racism.[77] It was reported at the time that the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was somewhat overshadowed by the anti-communist encyclical Divini Redemptoris which was issued on 19 March in order to avoid the charge by the Nazis that the Pope was indirectly favoring communism.[78]

Following the issuing of the document, The Catholic Herald reported that it was a "great Encyclical in fact contains a summary of what most needs preserving as the basis for a Christian civilisation and a compendium of the most dangerous elements in Nazi doctrine and practice."[79] and that:

Only a small portion of the Encyclical is against Germany's continuous violations of the Concordat; the larger part refers to false and dangerous doctrines which are officially spread in Germany and to which the Holy Father opposes the teaching of the Catholic Church. The word National Socialism does not appear at all in the document. The Pope has not tried to give a full analysis of the National Socialist doctrine. That would, indeed, have been impossible, as the Nazi movement is relatively young and it is doubtful whether certain ideas are "official" and essential parts of its doctrine or not. But one thing is beyond any doubt: If you take away from the National Socialist "faith" those false dogmas which have solemnly been condemned by the Holy Father in his Encyclical, the remainder will not deserve to be called National Socialism.[65]

Austrian Bishop Gfoellner of Linz had the encyclical read from the pulpits of his diocese. The Catholic Herald reported:

The Bishop of Linz (Mgr. Gfoellner) who has always taken a very strong anti-Nazi and anti-Socialist stand in the district of Austria where there has been most trouble with both views, said before the reading of 'the document: "The fate of the Church in Germany cannot be a matter of indifference to us; it touches us very nearly." After indicating the reasons the Bishop added that the dangers of German Catholics were also the dangers of Austrian Catholics: "What I wrote in my pastoral of January 21, 1933. It is impossible to be at once a good Catholic and a good National-Socialist,' is confirmed today." Mgr. Gfoellner asked all Catholic parents to keep their children away from any organisation which sympathised with the ideology condemned by the Pope.[80]

In April 1938 The Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano displayed for the first time "the historic headline" of "Religious Persecution in Germany" and reflected that what Pius XI had published in Mit brennender Sorge was now being clearly witnessed: "Catholic schools are closed, people are coerced to leave the Church … religious instruction of the Youth is made impossible ... Catholic organisations are suppressed … a press campaign is made against the Church, while its own newspapers and magazines are suppressed …"[81]

Assessments

editThe historian Eamon Duffy wrote:

In a triumphant security operation, the encyclical was smuggled into Germany, locally printed, and read from Catholic pulpits on Palm Sunday 1937. Mit brennender Sorge (With Burning Anxiety) denounced both specific government actions against the Church in breach of the concordat and Nazi racial theory more generally. There was a striking and deliberate emphasis on the permanent validity of the Jewish scriptures, and the Pope denounced the 'idolatrous cult' which replaced belief in the true God with a 'national religion' and the 'myth of race and blood'. He contrasted this perverted ideology with the teaching of the Church in which there was a home 'for all peoples and all nations'. The impact of the encyclical was immense, and it dispelled at once all suspicion of a Fascist Pope. While the world was still reacting, however, Pius issued five days later another encyclical, Divini Redemptoris, denouncing Communism, declaring its principles "intrinsically hostile to religion in any form whatever", detailing the attacks on the Church which had followed the establishment of Communist regimes in Russia, Mexico and Spain, and calling for the implementation of Catholic social teaching to offset both Communism and 'amoral liberalism'. The language of Divini Redemptoris was stronger than that of Mit brennender Sorge, its condemnation of Communism even more absolute than the attack on Nazism. The difference in tone undoubtedly reflected the Pope's own loathing of Communism as the "ultimate enemy."[82]

Carlo Falconi wrote:

So little anti-Nazi is it that it does not even attribute to the regime as such, but only to certain trends within it, the dogmatic and moral errors widespread in Germany. And while the errors indicated are carefully diagnosed and refuted, complete silence surrounds the much more serious and fundamental errors associated with Nazi political ideology, corresponding to the principles most subversive of natural law that are characteristic of absolute totalitarianisms. The encyclical is in fact concerned purely with the Catholic Church in Germany and its rights and privileges, on the basis of the concordatory contracts of 1933. Moreover the form given to it by Cardinal Faulhaber, even more a super-nationalist than the majority of his most ardent colleagues, was essentially dictated by tactics and aimed at avoiding a definite breach with the regime, even to the point of offering in conclusion a conciliatory olive branch to Hitler if he would restore the tranquil prosperity of the Catholic Church in Germany. But that was the very thing to deprive the document of its noble and exemplary intransigence. Nevertheless, even within these limitations, the pontifical letter still remains the first great public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism, and the Pope's courage astonished the world. It was, indeed, the encyclical’s fate to be credited with a greater significance and content than it possessed.[83]

Historian Klaus Scholder observed that Hitler's interest in church questions seemed to have died in early 1937, which he attributes to the issuing of the encyclical and that "Hitler must have regarded the encyclical Mit brennender sorge in April 1937 almost as a snub. In fact it will have seemed to him to be the final rejection of his world-view by Catholicism".[84] Scholder wrote:

However, whereas the encyclical Divini Redemptoris mentioned Communism in Russia, Mexico and Spain directly by name, at the suggestion of Faulhaber the formulation of the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was not polemical, but accused National Socialism above all indirectly, by a description of the foundations of the Catholic Church … As things were every hearer knew what was meant when it mentioned 'public persecution' of the faithful, 'a thousand forms of organized impediments to religion' and a 'lack of teaching which is loyal to the truth and of the normal possibilities of defence'. Even if National Socialism was not mentioned by name, it was condemned clearly and unequivocally as an ideology when the encyclical stated 'Anyone who makes Volk or state or form of state or state authorities or other basic values of the human shaping of society into the highest of all norms, even of religious values … perverts and falsifies the divinely created and divinely commanded order of things.'[11]

Scholder adds that:

The time of open confrontation seemed to have arrived. However, it very soon emerged that the encyclical was open to different interpretations. It could be understood as a last and extreme way by which the church might maintain its rights and its truth within the framework of the concordat; but it could also be interpreted as the first step which could be and had to be followed by further steps.[39]

Martin Rhonheimer wrote:

The general condemnation of racism of course included the Nazis' anti-Semitic racial mania, and condemned it implicitly. The question, however, is not what the Church's theological position with regard to Nazi racism and anti-Semitism was in 1937, but whether Church statements were clear enough for everyone to realize that the Church included Jews in its pastoral concern, thus summoning Christian consciences to solidarity with them. In light of what we have seen, it seems clear that the answer to this question must be No. In 1937 the Church was concerned not with the Jews but with entirely different matters that the Church considered more important and more urgent. An explicit defense of the Jews might well have jeopardized success in these other areas.

He further writes

Such statements require us to reconsider the Church's public declarations about the Nazi concept of the state and racism in the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge. Not only were Church declarations belated. They were also inadequate to counter the passivity and widespread indifference to the fate of Jews caused by this kind of Christian anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism, especially when it was combined with newly awakened national pride. The encyclical, then, came far too late to be of any help to Jews. In reality, however, the Church's statements were never really designed to help the Jews. The "Catholic apologetic" described above is something developed after the fact and has no roots in the historical record. Indeed, given the dominant view of the Jews in the Nazi period, it would have been astonishing if the Church had mounted the barricades in their defense. As we shall see, the failure of Church statements about Nazism and racism ever to mention the Jews specifically (save in negative ways) corresponds to an inner logic that is historically understandable—but no less disturbing to us today.[85]

Guenter Lewy wrote:

Many writers, influenced in part by the violent reaction of the Nazi government to the papal pronouncement, have hailed the encyclical letter Mit brennender Sorge as a decisive repudiation of the National Socialist state and Weltanschauung. More judicious observers have noted the encyclical was moderate in its tone and merely intimated that the condemned neopagan doctrines were favored by the German authorities. It is indeed a document in which, as one Catholic writer has put it, "with considerable skill, the extravagances of German Nazi doctrine are picked out for condemnation in a way that would not involve the condemnation of political and social totalitarianism{ … While some of Pius' language is sweeping and can be given a wider construction, basically the Pope had condemned neopaganism and the denial of religious freedom – no less and no more[86]

Catholic holocaust scholar Michael Phayer concludes that the encyclical "condemned racism (but not Hitler or National Socialism, as some have erroneously asserted)".[87] Other Catholic scholars have regarded the encyclical as "not a heatedly combative document" as the German episcopate, still ignorant of the real dimension of the problem, still entertained hopes of a Modus vivendi with the Nazis. As a result, the encyclical was "not directly polemical" but "diplomatically moderate", in contrast to the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno dealing with Italian fascism.[88]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Church and state through the centuries", Sidney Z. Ehler & John B Morrall, pp. 518–519, org pub 1954, reissued 1988, Biblo & Tannen, 1988, ISBN 0-8196-0189-6

- ^ a b c d e Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.58

- ^ "Before 1931 all such messages [encyclicals] were written in Latin. The encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno of June 29, 1931, which condemned certain theories and practices of Italian Fascism, particularly in the realm of education, and denounced certain treaty violations of Signor Mussolini's Government, was the first document of that kind that appeared in a language other than Latin." The Catholic Herald, "First Encyclical in German", PAGE 3, 9 April 1937 [1] Archived 27 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robert A. Ventresca – p.iv of photos, Soldier of Christ

- ^ a b Paul O'Shea, A Cross too Heavy, p.156-157

- ^ Martin Rhonheimer, The Holocaust: What Was Not Said, First Things 137 (November 2003): 18–28

- ^ Mit brennnder Sorge, § 30 in English version

- ^ Mit brennender Sorge Para 3

- ^ The Roman Catholic periodical The Tablet reported at the time "The Encyclical, which took the Nazi Government completely unawares, had been introduced into Germany by the diplomatic bag to the Nunciature, and Monsignor Orsenigo, Apostolic Nuncio in Berlin had arranged for its secret distribution all over the country so that it was read in every Catholic church of the Reich last Sunday, before the Government had time to confiscate and suppress it.", The Tablet, 3 April 1937, p.10 [2] Archived 26 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p. 381–382

- ^ a b Scholder, p. 154-155

- ^ The Catholic periodical The Tablet reported shortly after the issuing of the encyclical "The case in the Berlin court against three priests and five Catholic laymen is, in public opinion, the Reich's answer to the Pope's Mit brennender Sorge encyclical, as the prisoners have been in concentration camps for over a year. Chaplain Rossaint of Dusseldorf is, however, known as a pacifist and an opponent of the National Socialist regime, and it is not denied that he was indiscreet; but he is, moreover, accused of having tried to form a Catholic-Communist front on the plea that he baptized a Jewish Communist. This the accused denies, and his defence has been supported by Communist witnesses", The Tablet, p. 13, 24 April 1937 [3] Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McGonigle, p. 172: "the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was read in Catholic Churches in Germany. In effect it taught that the racial ideas of the leader (Führer) and totalitarianism stood in opposition to the Catholic faith; Bokenkotter, pp. 389–392; Historian Michael Phayer wrote that the encyclical doesn't condemn Hitler or National Socialism, "as some have erroneously asserted" (Phayer, 2002), p. 2; "His encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was the 'first great official public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism' and even described the Führer himself as a 'mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance.'"; Rhodes, pp. 204–205: "Mit brennender Sorge did not prevaricate … Nor was the Führer himself spared, for his 'aspirations to divinity', 'placing himself on the same level as Christ': 'a mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance' (widerliche Hochmut)."; "It was not the case that Pius failed to "spare the Führer," or called him a "mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance." The text limits its critique of arrogance to unnamed Nazi "reformers" (John Connelly, Harvard University Press, 2012, "From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965", p. 315, fn 52)

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Company; London; p.332

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Company; London; p.290

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.295

- ^ Three Popes and the Jews, Pinchas Lapide, 1967, Hawthorn Press, p. 102

- ^ Lewy, 1964, p. 92

- ^ a b Lewy, 1964, p. 93

- ^ The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942

- ^ Paul O'Shea; A Cross Too Heavy; Rosenberg Publishing; p. 234-5; ISBN 978-1-877058-71-4

- ^ Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.57

- ^ Joachim Fest; Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler 1933–1945; Weidenfeld & Nicolson; London; p.31

- ^ Falconi, 1967, p. 227

- ^ a b William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; p234-5

- ^ Peter Hoffmann; The History of the German Resistance 1933–1945; 3rd Edn (First English Edn); McDonald & Jane's; London; 1977; p.14

- ^ Lewy, 1967, p. 228

- ^ a b Falconi, 1967, p. 228

- ^ a b c Falconi, 1967, p. 229

- ^ Paul O'Shea, A Cross too Heavy, p.156

- ^ Joachim Fest; Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler 1933–1945; Weidenfeld & Nicolson; London; p.32"

- ^ Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; pp.58–59

- ^ Konrad Graf von Preysing; German Resistance Memorial Centre, Index of Persons; retrieved at 4 September 2013

- ^ Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair – German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ISBN 0-674-63680-5; p. 140

- ^ Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.59

- ^ Pham, Heirs of the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession (2005), p. 45

- ^ a b c The Papacy, the Jews, and the Holocaust, Frank J. Coppa, pp. 162–163, CUA Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8132-1449-1

- ^ Robert Ventresca, Soldier of Christ, p.118; "The word National Socialism does not appear at all in the document. The Pope has not tried to give a full analysis of the National Socialist doctrine. That would, indeed, have been impossible, as the Nazi movement is relatively young and it is doubtful whether certain ideas are "official" and essential parts of its doctrine or not.", The Catholic Herald, p. 3, 9 April 1937 [4]

- ^ a b Scholder, Requiem for Hitler, p. 159

- ^ Lewy, 1967, p. 156

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mit brennender Sorge Eng, Vatican Web Site

- ^ a b c d e f Lewy, 1967, p. 157

- ^ Phayer, Pius XII, The Holocaust, and the Cold War, 2008, p. 175-176

- ^ Faulhaber's original draft of this passage read: "Be vigilant that race, or the state, or other communal values, which can claim an honorable place in worldly things, be not magnified and idolized."

- ^ a b First things, Rhonheimer

- ^ Vidmar, pp. 327–331

- ^ Wills, Papal Sin, p. 19

- ^ "Anthony Rhodes - Cosmopolitan travel writer, biographer, novelist and memoirist". 25 August 2004.

- ^ "Anthony Rhodes: Cosmopolitan and well-connected man of letters who write a deeply researched three-volume history of the Vatican", Obituary, The Times, 8 September 2004 [5][dead link]

- ^ The Vatican in the Age of the Dictators, pp 204–205

- ^ e.g see Bokenkotter, pp. 389–392

- ^ John Connelly, Harvard University Press, 2012, "From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965", p. 315, fn 52

- ^ Phyaer, 2002, p. 2

- ^ Burleigh, p. 191-192

- ^ Under His Very Windows, p. 22

- ^ a b Burleigh, 2006, p. 191

- ^ a b Burleigh, 2006, p. 192

- ^ ""Mit brennender Sorge", the cry of Pius XI", Emma Fattorini, Reset Dialogues on Civilizations, 25 November 2008 [6]

- ^ "Religion and the Global Politics of Human Rights", Thomas Banchoff, Robert Wuthnow, Oxford University Press, pp. 291–292, 2011. ISBN 0199841039

- ^ Burleigh, 2005, p. 192

- ^ a b Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s, p. 511 ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ Bokenkotter 389

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Co; London; pp. 381–82

- ^ a b Ian Kershaw p.381-382

- ^ a b "First Encyclical in German", Catholic Herald, 9 April 1937

- ^ "German 'Traitor' Priests", Catholic Herald, 23 April 1937

- ^ ""The Church Abroad", 24 April 1937, The Tablet". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Rhodes, p. 205

- ^ Falconi, p. 230.

- ^ Scholder, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Vidmar, p. 254.

- ^ Rhodes, Anthony (1973). Vatican in the Age of the Dictators, 1922–1945. Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 202–210. ISBN 0-340-02394-5.

- ^ "National Socialist Culture", Catholic Herald, 15 Oct 1937

- ^ "Justice and Christianity Identified", Catholic Herald, Set 9 1938

- ^ Ian Kershaw; The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation; 4th Edn; Oxford University Press; New York; 2000; pp 210–11

- ^ Martin Rhonheimer, What was not Said Archived 18 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mit brennnder Sorge, §§ 8, 10, 11, 17, 23 in English version

- ^ The Church And Germany, The Catholic Herald, "The Church And Germany", Page 8, 16 April 1937 [7]

- ^ "The Church And Germany", Catholic Herald, 16 April 1937

- ^ "Austrian Bishop's Plain Words: Can't Be Good Nazi and Good Catholic", Catholic Herald, 16 April 1937 [8]

- ^ "HISTORIC HEADLINE 'Religious Persecution in Germany'", Catholic Herald, 6 May 1938 [9]

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07332-1. (paperback edition) p. 343

- ^ Falconi, 1967, pp 229–231

- ^ Scholder, p. 152, p. 163

- ^ "The Holocaust: What Was Not Said", First Things 137 (November 2003): 18–28.

- ^ Lewy, Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, 1964, p. 158-159

- ^ Phayer 2000, p. 2

- ^ "Church and state through the centuries", Sidney Z. Ehler & John B Morrall, pp. 518–519, org pub 1954, reissued 1988, Biblo & Tannen, 1988, ISBN 0-8196-0189-6

Sources

edit- Bokenkotter, Thomas (2004). A Concise History of the Catholic Church. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50584-1.

- Chadwick, Owen (1995). A History of Christianity. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0-7607-7332-7.

- Coppa, Frank J. (1999). Controversial Concordats. Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0920-3.

- Courtois, Stéphane; Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- Duffy, Eamon (1997). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07332-1.

- Falconi, Carlo (1967). The Popes in the Twentieth Century. Feltrinelli Editore. 68-14744.

- McGonigle (1996). A History of the Christian Tradition: From its Jewish roots to the Reformation. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3648-3.

- Norman, Edward (2007). The Roman Catholic Church, An Illustrated History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25251-6.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- Pham, John Peter (2006). Heirs of the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517834-3.

- Phayer, Michael (2000). The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21471-8.

- Rhodes, Anthony (1973). The Vatican in the Age of the Dictators (1922–1945). Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-340-02394-5.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- Vidmar, John (2005). The Catholic Church Through the Ages. Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-4234-1.

- Scholder, Klaus (1989). Requiem For Hitler. SCM Press. ISBN 0334022959.

- Peter Rohrbacher (2016). The Race Debate in the Curia in the Context of “Mit brennender Sorge” In: Fabrice Bouthillon, Marie Levant (Hrsg.): Un pape contre le nazisme? L'encyclique "Mit brennender Sorge" du pape Pie XI. (14 mars 1937). Actes du colloque international de Brest, 4–6 juin 2015. Editions Dialogues, Brest 2016, S. 93–108.

External links

edit- Mit brennender Sorge on Vatican.va (in English) (The section numbering differs from the German version.)

- Mit brennender Sorge on Vatican.va (in German)

- "'Morality Trials' In The Third Reich" Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Tablet 20 June 1936

- "An Open Letter to Dr. Goebbels" Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Tablet 17 July 1937