Miranda is a 1948 black and white British comedy film, directed by Ken Annakin and written by Peter Blackmore, who also wrote the play of the same name from which the film was adapted. The film stars Glynis Johns, Googie Withers, Griffith Jones, Margaret Rutherford, John McCallum and David Tomlinson. Denis Waldock provided additional dialogue. Music for the film was played by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Muir Mathieson. The sound director was B. C. Sewell.

| Miranda | |

|---|---|

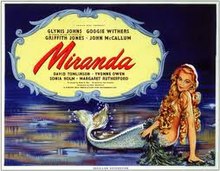

UK release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Annakin |

| Written by | Peter Blackmore additional dialogue Denis Waldock |

| Based on | Miranda by Peter Blackmore |

| Produced by | Betty E. Box |

| Starring | Glynis Johns Googie Withers Griffith Jones Margaret Rutherford John McCallum David Tomlinson |

| Cinematography | Ray Elton Bryan Langley (uncredited) |

| Edited by | Gordon Hales |

| Music by | Temple Abady |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | J. Arthur Rank General Film Distributors (UK) Eagle-Lion Films (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £170,400[1][2] |

| Box office | £181,300 (by Dec 1949)[1] or £176,000[3] |

The film is a light comedy fantasy about a beautiful and playful mermaid Miranda and her effect on the men and women she meets, as she outrageously flirts with and flatters every man she meets.

Glynis Johns and Margaret Rutherford reprised their roles in the 1954 colour sequel, Mad About Men.

Plot summary

editAs his wife is uninterested in fishing, Dr. Paul Martin goes on a holiday on the Cornwall coast without her. There, Miranda, a mermaid, catches him by pulling on his fishing line and making him fall in the water. She drags him down to her underwater cavern where she keeps him prisoner for a week and only lets him go after he agrees to show her London, where he lives. Having ordered several extra long dresses from his wife's London couturier to cover her tail, he disguises her as an invalid patient in a bath chair and takes her to his home, initially for a three weeks stay.

Martin's wife Clare reluctantly agrees to the arrangement, but insists he hire someone to look after the "patient". He selects Nurse Carey for her eccentric nature and takes her into his confidence. To Paul's relief, Carey is delighted to be working for a mermaid as she has always believed they exist.

Miranda's seductive nature earns her the admiration of not only Paul, but also his chauffeur Charles, as well as Nigel, the fiancé of Clare's friend and neighbour Isobel, arousing the jealousy of the women. Nigel even breaks off his engagement, but when he and Charles discover that Miranda has been flirting with both of them, they come to their senses.

With Clare strongly suspecting that Miranda is a mermaid, she makes Martin admit it. But when Miranda overhears Clare telling Paul that the public must be told, Miranda wheels herself down to the Thames and makes her escape into the water. She had previously told them she would go to Majorca for a visit.

In the final scene, Miranda is shown on a rock, holding a merbaby on her lap.

Cast

edit- Glynis Johns as Miranda Trewella

- Googie Withers as Clare Martin

- Griffith Jones as Dr Paul Martin

- John McCallum as Nigel

- Margaret Rutherford as Nurse Carey

- David Tomlinson as Charles

- Yvonne Owen as Betty, the Martins' other servant and Charles's girlfriend

- Sonia Holm as Isobel

- Brian Oulton as Manell

- Zena Marshall as Secretary

- Lyn Evans as Inn Landlady

- Stringer Davis as Museum Attendant

- Hal Osmond as Railway Carman

- Maurice Denham as Cockle Vendor

Original play

editThe film was based on a play by Peter Blackmore. He says he was inspired to write it after reading a scientific article about mermaids.[4]

In the play on which the film is based, Miranda eventually has to return to Cornwall to spawn, much to the displeasure of Martin's wife.

The play was a hit in London – starring Genine Graham – and had a run in New York with Diana Lynn.[5][6]

Production

editThe film was put into production hurriedly in order to beat Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid to the screen.[7] The initial director was Michael Chorlton.[8] According to Ken Annakin, filming had been going for less than two weeks when Chorlton was fired by the head of the studio, Sydney Box, who was unhappy with the director's handling of the material, particularly his over-use of wide-angle, deep focus camera techniques. Box asked Annakin, who had just finished filming Broken Journey to take over, which the director reluctantly did after Box pointed out it was either him or someone else. Annakin took over with three days of preparation.[9]

Annakin said the "script was full of well-tried, funny fishy jokes" and "was inevitably going to be a stagey-type movie."[10] He says he "despised" Griffith Jones "as a man" because he was difficult to deal with, "always trying to score over the other actors."[10] Annakin says he developed a crush on Johns during filming and she tried to seduce him one night (she was married but her husband was gay) - but he refused because he did not want her to have power over him. They went on to make six more films together.[11]

The opening credits include the line "Tail by Dunlop". All underwater scenes were shot with a stunt double. Joan Hebden[citation needed] wore the tail by Dunlop. Glynis Johns stated in later interviews that the rubber tail was very buoyant, which caused problems as it tended to keep her head under the water.[12]

There was location filming in London and Cornwall.[13]

Reception

editCritical

editThe Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "Here is a pleasant little comedy which brings a welcome change of temper to the contemporary British screen. The dialogue is witty, the situations well contrived, even if the joke wears a bit thin by the end and some of the effects are laboured. Glynis Johns makes a most enchanting mermaid, sophisticated and not at all 'hey nonny'. Margaret Rutherford gives a characteristically exuberant performance as the eccentric nurse, dancing the Mazurka or carrying out more domestic duties with equal zest. David Tomlinson is an amusing chauffeur, Griffith Jones does well as Paul, and Googie Withers, as his wife, acts with customary assurance."[14]

Variety wrote: "Everything is rightly played for laughs and Glynis Johns makes the mermaid an attractive and almost credible creature. Griffith Jones is good as her serious sponsor. Googie Withers turns in a nice performance as his bewildered wife, and David Tomlinson and John McCallum do well as the lovestruck swains. As nurse to the mermaid, Margaret Rutherford gets plenty of laughs, but occasionally descends to unnecessary burlesque."[15]

Box office

editThe film was one of the most popular movies at the British box office in 1948.[16][17] According to Kinematograph Weekly Miranda was one of the runners-up for 'biggest winner' at the box office.[18]

Producer's receipts were £143,400 in the UK and £32,600 overseas[19] meaning it recorded a profit of £5,600.[1] Annakin says the film was not popular in America at all due to the release of Mr Peabody and the Mermaid; he claims the makers of that movie threatened to sue Gainsborough Pictures for copyright infringement but the latter were protected by the fact it was based on a play.[20]

DVD release

editThe film was released on home video for the first time in North America on DVD on 5 July 2011 from VCI Entertainment.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Spicer, Andrew (2006). Sydney Box. Manchester Uni Press. p. 210. ISBN 9780719059995.

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 354.

- ^ Chapman p 354. Income is in terms of producer's share of receipts.

- ^ "FILM NEWS". Coolgardie Miner. Vol. VIII, no. 744. Western Australia. 8 September 1949. p. 1 (MODERN WEEKLY News Magazine). Retrieved 31 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ GLADWIN, H. A. (20 June 1948). "NEW LOOK FOR COAST STRAW HATS". New York Times. ProQuest 108105115.

- ^ Hayward, Philip (2017). Making a Splash: Mermaids (and Mer-Men) in 20th and 21st Century Audiovisual Media. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780861969258.

- ^ "Glynis Johns has a mermaid tail in "Miranda"". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 15, no. 6. 19 July 1947. p. 36. Retrieved 31 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Andrew Spicer, "The Apple of Mr. Rank's Mercatorial Eye’: Managing Director of Gainsborough Pictures

- ^ Annakin p 33

- ^ a b Annakin p 34

- ^ Annakin p 36-38

- ^ "- YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ "Miranda". Reel Streets. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "Miranda". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 15 (169): 47. 1 January 1948 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Miranda". Variety. 170 (6): 8. 14 April 1948 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "THE STARRY WAY". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane. 8 January 1949. p. 2. Retrieved 11 July 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 258.

- ^ Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout : reinventing women for wartime British cinema. Princeton University Press. p. 232.

- ^ Chapman p 354

- ^ Annakin p 36

Citation

edit- Annakin, Ken (2001). So you wanna be a director?. Tomahawk Press.

External links

edit- Miranda at IMDb

- Miranda at the TCM Movie Database

- Miranda at AllMovie

- Miranda at BFI Screenonline

- Review of film at Variety

- Miranda at Rotten Tomatoes