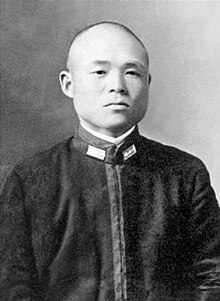

Minoru Ōta (大田 実, Ōta Minoru, 7 April 1891 – 13 June 1945) was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, and the final commander of the Japanese naval forces defending the Oroku Peninsula during the Battle of Okinawa.

Minoru Ōta | |

|---|---|

Admiral Minoru Ōta | |

| Native name | 大田 実 |

| Born | 7 April 1891 Nagara, Japan |

| Died | 13 June 1945 (aged 54)[1] Okinawa, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1913–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | |

Biography

editŌta was a native of Nagara, Chiba. He graduated 64th out of 118 cadets from the 41st class of the Imperial Japanese Navy Academy in 1913. Ōta served his midshipman duty on the cruiser Azuma on its long-distance training voyage to Honolulu, San Pedro, San Francisco, Vancouver, Victoria, Tacoma, Seattle, Hakodate and Aomori. After his return to Japan, he was assigned to the battleship Kawachi, and after he was commissioned an ensign, to the battleship Fusō. After promotion to lieutenant in 1916, he returned to naval artillery school, but was forced to take a year off active service from November 1917 to September 1918 due to tuberculosis. On his return to active duty, he completed coursework in torpedo school and advanced courses in naval artillery. After brief tours of duty on the battleships Hiei and Fusō, he returned as an instructor at the Naval Engineering College.[2]

Ōta also had experience with the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF, the Japanese equivalent of the Royal Marines), as he had been assigned command of a battalion of SNLF forces in the 1932 First Shanghai Incident. He was promoted to commander in 1934. In 1936, he was named executive officer of the battleship Yamashiro, and was finally given his first command, that of the oiler Tsurumi in 1937. He was promoted to captain in December the same year.[2]

World War II

editIn 1938, with the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Ōta was assigned to command the Kure 6th SNLF. In 1941, he was assigned to the command of the SNLF under the Japanese China Area Fleet at Wuhan in China. He returned to Japan the following year, and was assigned to command the 2nd Combined Special Naval Landing Force that was earmarked for the seizure of Midway in the event of a Japanese victory over the United States Navy at the Battle of Midway.[3] Although this never came to pass, he was promoted to rear admiral and commanded the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force at New Georgia against the American First Raider Battalion.[4] He then served in various administrative capacities until January 1945, when he was reassigned to Okinawa to command the Japanese Navy's forces as part of the Japanese reinforcement effort prior to the anticipated invasion by Allied forces.[5][6]

In Okinawa, Ōta commanded a force with a nominal strength of 10,000 men. However, half were civilian laborers conscripted into service with minimal training, and the remainder were gunners from various naval vessels with little experience in fighting on land. Allied sources are contradictory on his role as commander of the naval elements in Okinawa. Some cite Ōta as able to organize and lead them into an effective force, which fought aggressively against the Allied forces, "withdrawing slowly back to the fortified Oroku Peninsula."[7] But Naval elements, except for outlying islands were headquartered on the Oroku peninsula from the beginning of the battle.[8] Operations Planning Colonel Hiromichi Yahara of the Japanese 32nd Army describes a miscommunication occurring in the order for Ota's Naval elements to withdraw from the Oroku Peninsula to support the army further south.[8] What actually happened is clear: Ōta began preparations on or around 24 May, for the withdrawal of all Naval elements to the south in support of the Army. He destroyed most heavy equipment, stocks of ammunition and even personal weapons. While in mid-march to the south, 32nd Army HQ ordered Ōta back into the Oroku peninsula citing that a mistake had been made in timing (explanations vary). Naval elements returned to their former positions with no heavy weapons and about half the troops had no rifles. The Americans, who had not noticed the initial withdrawal attacked and cut off the peninsula by attacks from the north on land, and one last seaborne landing behind the Navy's positions. Naval elements then committed suicide with whatever weapons possible, with some leading a last charge out of the cave entrances. According to the museum for the underground Naval Headquarters in Okinawa, "many soldiers committed suicide" inside the command bunker, including Ōta.[9]

Ōta committed suicide here.

On June 6, Commanding Officer Ota sent out a telegram to the Navy Vice admiral.[10] On 11 June 1945, the U.S. 6th Marine Division encircled Ōta's positions, and Ōta sent a farewell telegram to the IJA 32nd Army Headquarters at 16:00 on 12 June. On 13 June, Ōta committed suicide with a handgun. He was posthumously promoted to vice admiral.[citation needed]

Telegraph to the Navy Vice Admiral

edit(There are illegible parts.)

From the commander of Okinawa military To the vice minister of Navy ministry

Please pass this telegram to vice minister (illegible).

Sent at 20:16 on the 6th of June, 1945:

"Regarding the actual situation of Okinawa citizens, the prefectural governor should report it. But the prefectural office has already lost communication means and the 32nd Army Headquarters does not seem to have the excess communication capacity neither. So I will inform you of the situation in lieu of the governor although it was not requested from the prefectural governor to the Navy Headquarters. I simply can not overlook the current situation as it is.

Since the enemy began to attack the main island of Okinawa, the Navy and the Army devoted themselves to defensive warfare and could hardly look after the prefecture's people.

However, as far as I can tell, among the prefectural people, all the young and middle-aged males responded fully to the defensive convocation altogether. Old men, children and women who were left behind to fend for themselves are now forced to lead starved miserable lives exposed to natural elements. They initially hid themselves in small air shelters dug in areas originally thought to be free from military operations after they had lost all their belongings, living quarters and household items, due to repetitive naval shelling and air raids. But these shelters also have been bombarded and so they have been forced to flee.

Despite the hardship, young women have taken the initiative to devote themselves to the military: many as nurses and cooks and some even offered to carry cannonballs and even serve in the sword-waving attack units.

Local civilians expect the ominous outcome once the enemy lands:, the old men and children shall be killed, and women shall be taken away to the enemy's territory for nefarious purposes. So some parents have decided to leave their young daughters at the gates of military camps seeking military protection for them.

I should add the devotion of young female local nurses: they continue to help the seriously injured soldiers left behind after the military movement and medics are no longer available. The dedication of these nurses is very serious and I do not believe it is driven by an ephemeral feeling of sympathy.

Furthermore, I have seen people without transport means walk in the evening rain without complaints at all when a sudden and drastic change of the military strategy dictated that these civilians relocate to a far away place at short notice at night.

To sum up, despite consistent heavy burden of labor service and lack of goods all the time since the Imperial Navy and Army proceeded to establish the front line in Okinawa, (despite some bad rumors of a few parties) the local citizens devoted themselves to the loyal service as Japanese (illegible) without giving (illegible) Okinawa Islands will become scorched land where no single plant will remain unburned.

It is said that food shall be sufficient only up to the end of June.

The Okinawa citizens fought this way. I would humbly request your esteemed preferred consideration to the prefectural people in the future".

References

edit- Alexander, Joseph H. (1997). Storm Landings: Epic Amphibious Battles in the Central Pacific. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-032-0.

- Astor, Gerald (1996). Operation Iceberg : The Invasion and Conquest of Okinawa in World War II. Dell. ISBN 0-440-22178-1.

- Feifer, George (2001). The Battle of Okinawa: The Blood and the Bomb. The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-215-5.

- Lacey, Laura Homan (2005). Stay Off The Skyline: The Sixth Marine Division on Okinawa—An Oral History. Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-952-4.

- Leckie, Robert (1997). Strong Men Armed: The United States Marines Against Japan. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80785-8.

- Prange, Gordon W (1983). Miracle at Midway. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-006814-7.

- Wiest, Andrew A (2001). The Pacific War: Campaigns of World War II. Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-7603-1146-3.

External links

edit- Nishida, Hiroshi. "Imperial Japanese Navy". Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

Notes

edit- ^ Nishida, Hiroshi, Imperial Japanese Navy

- ^ a b "Materials of IJN (Naval Academy class 41)". Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Prange, Miracle at Midway, page 63

- ^ Alexander. Storm Landings. Page 206

- ^ Astor. Operation Iceberg. page 462.

- ^ Weist. The Pacific War:Campaigns of World War II. page 223

- ^ Feifer, The Battle of Okinawa.

- ^ a b Yahara, Michihiro "The Battle for Okinawa"

- ^ "壕について | ≪公式≫ 旧海軍司令部壕 (海軍壕公園)". Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ http://kaigungou.ocvb.or.jp/pdf/eigopan.pdf Archived 16 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]