Vieques (/viˈeɪkəs/ ⓘ; Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbjekes]), officially Isla de Vieques, is an island, town and municipality of Puerto Rico, and together with Culebra, it is geographically part of the Spanish Virgin Islands. Vieques lies about 8 miles (13 km) east of the mainland of Puerto Rico, measuring about 20 miles (32 km) long and 4.5 miles (7 km) wide. Its most populated barrio is the town of Isabel Segunda (or "Isabel the Second", sometimes written "Isabel II"), the administrative center located on the northern side of the island. The population of Vieques was 8,249 at the 2020 Census.

Vieques

Municipio Autónomo de Vieques Isla de Vieques | |

|---|---|

Island-Municipality | |

Mosquito Bioluminescent Bay in Vieques | |

| Nicknames: "Isla Nena", "Isabel Segunda" | |

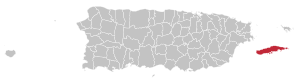

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Vieques Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°07′N 65°25′W / 18.117°N 65.417°W | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Indigenous settlement | 3000 – 2000 BCE |

| Spanish settlement | 1811 |

| Isabel II founded | 1843 – 1852 |

| Municipality founded | July 1, 1875 |

| Founded by | Teófilo José Jaime María Le Guillou |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | José (Junito) Corcino Acevedo (PNP) |

| • Senatorial District | 8 – Carolina |

| • Representative District | 36 |

| Area | |

• Total | 135 km2 (52 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 8,249 |

| • Rank | 76th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 61/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Viequense |

| Racial groups | |

| • White | 48.7% |

| • Black | 38.1% |

| • American Indian/AN | 0.4% |

| • Asian - Native Hawaiian/Pi | 0.6% 0.8% |

| • Other Two or more races | 8.8% 3.4% |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Code | 00765 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

The island's name is a Spanish spelling of a Taíno word said to mean "small island" or "small land". It also has the nickname Isla Nena, usually translated as "girl island" or "little girl island", alluding to its perception as Puerto Rico's little sister. The island was given this name by the Puerto Rican poet Luís Lloréns Torres. During the British colonial period, its name was Crab Island.

Vieques is best known internationally as the site of a series of protests, held against the United States Navy's use of the island as a bombing range and testing-ground, leading to the Navy's departure in 2003.[4] Today, the former navy lands are a national wildlife refuge; some of it is open to the public, but much remains closed off due to biological or chemical contamination or unexploded ordnance that the military is, slowly, cleaning up.[5]

Some of the most beautiful beaches on the island are on the eastern end (former site of the Marine Base) that the Navy named Red Beach, Blue Beach, Caracas Beach, Pata Prieta Beach, La Chiva Beach, and Plata Beach. At the far western tip (formerly the Navy Base) is Punta Arenas, which the Navy named 'Green Beach'. The beaches are commonly listed among the top in the Caribbean for their azure waters and white sands.[6]

History

editPre-Columbian history

editArchaeological evidence suggests that Vieques was first inhabited by ancient Indigenous peoples of the Americas who traveled mostly from South America perhaps between 3000 BCE and 2000 BCE. Estimates of these prehistoric dates of inhabitation vary widely. These tribes had a Stone Age culture and were probably fishermen and hunter-gatherers.

Excavations at the Puerto Ferro site by Luis Chanlatte and Yvonne Narganes[7] uncovered a fragmented human skeleton in a large hearth area. Radiocarbon dating of shells found in the hearth indicate a burial date of c. 1900 BCE. This skeleton, popularly known as El Hombre de Puerto Ferro, was buried at the center of a group of large boulders near Vieques's south-central coast, approximately one kilometer northwest of the Bioluminescent Bay. Linear arrays of smaller stones radiating from the central boulders are apparent at the site today, but their age and reason for placement are unknown.

Further waves of settlement by Native Americans followed over many centuries. The Arawak-speaking Saladoid (or Igneri) people, thought to have originated in modern-day Venezuela, arrived in the region perhaps around 200 BC (estimates vary). These tribes, noted for their pottery, stone carving, and other artifacts, eventually merged with groups from Hispaniola and Cuba to form what is now called the Taíno culture. This culture flourished in the region from around 1000 AD until the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th century.

Spanish colonial period

editThe European discovery of Vieques is sometimes credited to Christopher Columbus, who landed in Puerto Rico in 1493. It does not seem to be certain whether Columbus personally visited Vieques, but in any case the island was soon claimed by the Spanish. During the early 16th century Vieques became a center of Taíno rebellion against the European invaders, prompting the Spanish to send armed forces to the island to quell the resistance. The native Taíno population was decimated, and its people either killed, imprisoned or enslaved by the Spanish.[8]

The Spanish did not, however, permanently colonize Vieques at this time, and for the next 300 years it remained a lawless outpost, frequented by pirates and outlaws. As European powers fought for control in the region, a series of attempts by the French, English and Danish to colonize the island in the 17th and 18th centuries were repulsed by the Spanish.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Spanish took steps to permanently settle and secure the island. In 1811, Don Salvador Meléndez, then governor of Puerto Rico, sent military commander Juan Rosselló to begin what would become the annexation of Vieques by the Puerto Ricans.[9]

In 1832, under an agreement with the Spanish Puerto Rican administration, Frenchman Teófilo José Jaime María Le Guillou became Governor of Vieques, and undertook to impose order on the anarchic province. He was instrumental in the establishment of large plantations, marking a period of social and economic change. Le Guillou is now remembered as the founder of Vieques (though this title is also sometimes conferred on Francisco Saínz, governor from 1843 to 1852, who founded Isabel Segunda, the main town in Vieques, named after Queen Isabel II of Spain). Vieques was formally annexed to Puerto Rico in 1854.

In 1816, Vieques was briefly visited by Simón Bolívar when his ship ran aground there while fleeing defeat in Venezuela.[10]

During the second part of the 19th century, thousands of slaves of African descent were brought to Vieques to work the sugarcane plantations. They arrived from mainland Puerto Rico and nearby islands of St. Thomas, Nevis, Saint Kitts, Saint Croix, and many other Caribbean islands. Slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico in 1873.[11]

European colonial period

editThe island also received considerable attention as a possible colony from Scotland, and after numerous attempts to buy the island proved unsuccessful, the Scottish fleet, en route to Darien in 1698, made landfall and took possession of the island in the name of the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and The Indies. Scottish sovereignty of the island proved short-lived, as a Danish ship arrived shortly afterward and claimed the island. From 1689 to 1693, the island was controlled by Brandenburg-Prussia as Krabbeninsel (German crab island), where the English name Crab Island came from.

United States control

editPuerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States conducted its first census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Vieques was 6,642 (but this included 704 residents from a nearby island, Culebra).[12]

In the 1920s and 1930s, the sugar industry, on which Vieques was dependent, went into decline due to falling prices and industrial unrest. Many locals were forced to move to mainland Puerto Rico or Saint Croix to look for work.

In 1941, while Europe was in the midst of World War II, the United States Navy purchased or seized almost eighty percent[13] of Vieques as an extension to the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station nearby on the Puerto Rican mainland. It is said that the original purpose of the base (never implemented) was to provide a safe haven for the British fleet and the British royal family should Great Britain fall to Nazi Germany.[14] This assertion does not match U.S. Navy documents and the obvious fact that Canada's Halifax harbor would have been a more likely fallback position for the British fleet, with British King George VI already reigning as King of Canada. The base was however seen as the Atlantic's counterpart of Pearl Harbor in the Pacific due to its strategic location. The Naval Station at Roosevelt Roads was a perfect location to defend the strategic approaches to the Panama Canal.

Much of the land was bought from the owners of large farms and sugar cane plantations, and the expropriations triggered the final demise of the sugar industry. Without consulting the local population who had lived and worked there for centuries and protested the expropriations,[15] the decision to turn it into a bombing range was made in Washington. In a similar way as the former population of the Chagos Islands, who were displaced to make way for an Air Force Base in the Indian Ocean in the 1960s, many agricultural workers, who had no formal title to the land they occupied, were evicted and forced to migrate.[16][17]

For over sixty years, the US military used the island (with a population of over 9000 inhabitants in 1950[18]) as a live munitions target practice. According to internal Navy documents, bombardments occurred on 180 days out of a year on average. The US military used the highest possible contaminant depleted uranium (DU) munitions since 1972 on the populated (and full of exotic wildlife) island, at a rate of over 80 live bombs daily for decades.[19][17] The health consequences are felt to this day as the cancer rates are ostensibly higher for the population of Vieques, especially children, than for those on the main island.[19]

After the war, the US Navy continued to use the island for military exercises, and as a firing range and testing ground for munitions.

Protests and departure of the United States Navy

editThe continuing postwar presence in Vieques of the United States Navy drew protests from the local community, angry at the expropriation of their land and the environmental impact of weapons testing. The locals' discontent was exacerbated by the island's perilous economic condition.

Protests came to a head in 1999 when Vieques native David Sanes, a civilian employee of the United States Navy, was killed by a jet bomb that the Navy said misfired. Sanes had been working as a security guard. A popular campaign of civil disobedience resurged; not since the mid-1970s had Viequenses come together en masse to protest the target practices.[20] The locals took to the ocean in their small fishing boats and successfully stopped the US Navy's military exercises for a short period, until the US Navy and two US Coast Guard cutters began controlling access to the island and escorting boaters away from Vieques.

On April 27, 2001, the Navy resumed operations and protesting resumed.[21] At this point over 600 protesters had already been detained.[22]

The Vieques issue became something of a cause célèbre, and local protesters were joined by sympathetic groups and prominent individuals from the mainland United States and abroad, including political leaders Rubén Berríos, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson, singers Danny Rivera, Willie Colón[23] and Ricky Martin, actors Edward James Olmos and Jimmy Smits, boxer Félix 'Tito' Trinidad, baseball superstar Carlos Delgado, writers Ana Lydia Vega and Giannina Braschi, and Guatemala's Nobel Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú. Kennedy's son, Aidan Caohman "Vieques" Kennedy,[24] was born while his father served jail time in Puerto Rico for his role in the protests. The problems arising from the US Navy base have also featured in songs by various musicians, including Puerto Rican rock band Puya, rapper Immortal Technique and reggaeton artist Tego Calderón. In popular culture, one subplot of "The Two Bartlets" episode of The West Wing dealt with a protest on the bombing range led by a friend of White House Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman; the character was modeled on future West Wing star Jimmy Smits, a native of Puerto Rico who was repeatedly arrested for leading protests there.

As a result of this pressure, in May 2003 the Navy withdrew from Vieques, and much of the island was designated a National Wildlife Refuge under the control of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[11] The island was also placed on the National Priorities List (NPL), the list of hazardous waste sites in the United States eligible for long-term remedial action (cleanup) financed by the federal Superfund program. Closure of Roosevelt Roads Naval Station followed in 2004, and prior to Hurricane Maria the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station was reopened.

A report by the Government Accountability Office was published in 2021 and estimated there were "8 million items of material potentially presenting an explosive hazard, and approximately 109,000 munitions items: 41,000 projectiles; 32,000 bombs; 4,700 mortars; 1,300 rockets; 18,000 submunitions; and 12,000 grenades, flares, pyrotechnics, and other munitions" that had been removed from the testing site, and that further cleanup was expected to continue by 2032.[25]

Hurricane Maria and rebuilding efforts

editPuerto Rico was struck by Hurricane Maria on September 20, 2017, and the storm caused widespread devastation and a near-total shutdown of the island's tourism-based economy. The largest hotel on the island, The W, has not reopened since the storm, but most smaller hotels, bed and breakfasts, and Airbnb operators have resumed operations.[26]

As of December 2019, the Susana Centeno Hospital in Vieques had not been repaired and remained shuttered. Expectant mothers had to travel to the main island of Puerto Rico to give birth. People needing dialysis had to travel to the main island. In November 2018, a mobile dialysis machine was delivered to a temporary clinic.[27]

On January 21, 2020, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) approved $39.5 million to help rebuild its only hospital after damage caused by Hurricane Maria. FEMA approved the funding after the Office of Management and Budget agreed to provide money to rebuild the Susan Centeno community health center based on its "replacement value."[28]

The family of Jaideliz Moreno Ventura, 13, whose 2020 death was blamed on the lack of a functioning hospital and lifesaving medical equipment in Vieques, is suing the government for violation of human and civil rights. Funds for rebuilding the hospital were approved two weeks after Jaideliz's death.[29]

While Governor Pedro Pierluisi expected construction to begin on the hospital rebuild in 2022,[30] it was delayed until 2023 with the holdup blamed on both construction complications on the island and further bureaucratic procedures by FEMA.[31] As of November 2024, construction was not yet complete.

Government

editVieques is a municipio of Puerto Rico, translated as "municipality" and in this context roughly equivalent to "township". All municipalities in Puerto Rico are administered by a mayor, elected every four years. The current mayor of Vieques is José "Junito" Corcino Acevedo, of the New Progressive Party (PNP). He was first elected at the 2020 general elections.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VIII, which is represented by two Senators. In 2024, Marissa Jiménez and Héctor Joaquín Sánchez Álvarez were elected as District Senators.[32]

Barrios

editwith barrios

Vieques is divided into eight barrios, including the downtown barrio called Isabel Segunda.[33][34]

| Barrio | Area (m2)[35] | Population (census 2000) |

Density | Cays and islets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isabel II barrio-pueblo | 696997 | 1459 | 2093.3 | — |

| Florida | 11553856 | 4126 | 357.1 | — |

| Llave | 15420815 | 8 | 0.5 | — |

| Mosquito | 6279364 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Puerto Diablo | 45323702 | 984 | 21.7 | Roca Cucaracha, Isla Yallis, Roca Alcatraz, Cayo Conejo, Cayo Jalovita, Cayo Jalova |

| Puerto Ferro | 21199791 | 856 | 40.4 | Isla Chiva, Cayo Chiva |

| Puerto Real | 19943599 | 1673 | 83.9 | Cayo de Tierra, Cayo de Afuera (Cayo Real) |

| Punta Arenas | 11227244 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Vieques | 131645368 | 9106 | 69.2 |

Sectors

editBarrios (which are like minor civil divisions)[36] are further subdivided into smaller areas called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[37][38][39]

Special Communities

editComunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Vieques: Sector Gobeo in Barrio Florida, Bravos de Boston, Jagüeyes, Monte Carmelo, Pozo Prieto (Monte Santo) and Villa Borinquén.[40]

Geography

editVieques measures about 21 miles (34 km) east-west, and three to four miles (6.4 km) north-south. It has a land area of 52 square miles (130 km2) and is located about ten miles (16 km) to the east of Puerto Rico. To the north of Vieques is the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south, the Caribbean. The island of Culebra is about 10 miles (16 km) north of Vieques, and the United States Virgin Islands lie to the east. Vieques and Culebra, together with various small islets, make up the Spanish Virgin Islands, sometimes known as the Passage Islands.[citation needed][41]

The former US Navy lands, now wildlife reserves, occupy the entire eastern and western ends of Vieques, with the former live weapons testing site (known as the "LIA", or "Live Impact Area") at the extreme eastern tip.[42] These areas are unpopulated. The former civilian area occupies very roughly the central third of the island and contains the towns of Isabel Segunda on the north coast, and Esperanza on the south.

Vieques has a terrain of rolling hills, with a central ridge running east–west. The highest point is Monte Pirata at 987 feet (301 m). Geologically the island is composed of a mixture of volcanic bedrock, sedimentary rocks such as limestone and sandstone, and alluvial deposits of gravel, sand, silt, and clay. There are no permanent rivers or streams. Much former agricultural land has been reclaimed by nature due to prolonged disuse, and, apart from some small-scale farming in the central region, the island is largely covered by brush and subtropical dry forest. Around the coast lie palm-fringed sandy beaches interspersed with lagoons, mangrove swamps, salt flats and coral reefs.[citation needed]

A series of nearshore islets and rocks are part of the municipality of Vieques, clockwise starting at the northernmost:

- Roca Cucaracha (a rock of less than five meters in diameter)

- Isla Yallis

- Roca Alcatraz

- Cayo Conejo

- Cayo Jalovita

- Cayo Jalova

- Isla Chiva

- Cayo Chiva

- Cayo de Tierra

- Cayo de Afuera (Cayo Real)

Bioluminescent Bay

editThe Vieques Bioluminescent Bay (also known as Puerto Mosquito, Mosquito Bay, or "The Bio Bay"), was declared the "Brightest bioluminescent bay" in the world by Guinness World Records in 2006,[43] and is listed as a national natural landmark, one of five in Puerto Rico. The luminescence in the bay is caused by a microorganism, the dinoflagellate Pyrodinium bahamense, which glows whenever the water is disturbed, leaving a trail of neon blue.

A combination of factors creates the necessary conditions for bioluminescence: red mangrove trees surround the water (the organisms have been related to mangrove forests[44] although mangrove is not necessarily associated with this species[45]); a complete lack of modern development around the bay; the water is warm enough and deep enough; and a small channel to the ocean keeps the dinoflagellates in the bay. This small channel was created artificially, the result of attempts by the occupants of Spanish ships to choke off the bay from the ocean. The Spanish believed that the bioluminescence they encountered there while first exploring the area was the work of the devil and tried to block ocean water from entering the bay by dropping huge boulders in the channel.[citation needed] The Spanish only succeeded in preserving and increasing the luminescence in the now isolated bay.

Kayaking is permitted in the bay and may be arranged through local vendors.

Climate

editVieques has a warm, relatively dry, tropical climate. Temperatures vary little throughout the year, with average daily maxima ranging from 84.7 °F (29.3 °C) in January to 89.9 °F (32.2 °C) in September. Average daily minima are about 18 °F or 6 °C lower. Rainfall averages around 40 to 45 inches (1,000 to 1,100 millimetres) per year, with the month of September being the wettest. The west of the island receives significantly more rainfall than the east. Prevailing winds are easterly.

Vieques is prone to tropical storms and at risk from hurricanes from June to November. In 1989, Hurricane Hugo caused considerable damage to the island,[46] and in 2017, Hurricane Maria also caused major damage.[47]

| Climate data for Vieques Island, Puerto Rico (1955–1976 normals, extremes 1955–1976) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 84.7 (29.3) |

85.2 (29.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

88.4 (31.3) |

89.4 (31.9) |

89.6 (32.0) |

89.7 (32.1) |

89.9 (32.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

87.9 (31.1) |

85.7 (29.8) |

87.8 (31.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 66.9 (19.4) |

66.6 (19.2) |

67.0 (19.4) |

68.1 (20.1) |

70.4 (21.3) |

71.7 (22.1) |

71.6 (22.0) |

71.7 (22.1) |

71.5 (21.9) |

70.9 (21.6) |

69.5 (20.8) |

67.8 (19.9) |

69.5 (20.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 55 (13) |

52 (11) |

54 (12) |

56 (13) |

59 (15) |

59 (15) |

60 (16) |

63 (17) |

63 (17) |

60 (16) |

61 (16) |

57 (14) |

52 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.74 (70) |

1.29 (33) |

1.31 (33) |

2.30 (58) |

4.40 (112) |

3.22 (82) |

3.16 (80) |

5.02 (128) |

5.25 (133) |

5.00 (127) |

4.98 (126) |

3.39 (86) |

42.06 (1,068) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[48] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 5,938 | — | |

| 1910 | 10,425 | 75.6% | |

| 1920 | 11,651 | 11.8% | |

| 1930 | 10,582 | −9.2% | |

| 1940 | 10,362 | −2.1% | |

| 1950 | 9,228 | −10.9% | |

| 1960 | 7,210 | −21.9% | |

| 1970 | 7,767 | 7.7% | |

| 1980 | 7,662 | −1.4% | |

| 1990 | 8,602 | 12.3% | |

| 2000 | 9,106 | 5.9% | |

| 2010 | 9,301 | 2.1% | |

| 2020 | 8,249 | −11.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[49] 1899 (shown as 1900)[50] 1910–1930[51] 1930–1950[52] 1960–2000[53] 2010[34] 2020[54] | |||

2020

editAccording to the 2020 Census, Vieques is the third-least populous municipality (after Maricao and Culebra) with a population of 8,249.[56]

8.0% of the population is of non-Hispanic origin, making it the second-least Hispanic municipality in Puerto Rico after Culebra. This represents an increase from 2010, when only 5.7% of the population was non-Hispanic.[57]

2010

editThe 2010 US census,[58] showed the total population of Vieques was 9,301. 94.3% of the population are Hispanic or Latino (of any race). Natives of Vieques are known as Viequenses.

| Self-defined race 2010[59] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of population |

| White | 5,456 | 48.7 |

| Black | 2,617 | 38.1 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native |

62 | 0.7 |

| Asian | 6 | 0.1 |

| Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander |

0 | 0 |

| Some other race | 688 | 7.4 |

| Two or more races | 309 | 3.4 |

Language

editBoth Spanish and English are recognized as official languages. Spanish is the primary language of most inhabitants.

Economy

editThe sugar industry, once the mainstay of the island's economy, declined during the early 20th century, and finally collapsed in the 1940s when the US Navy took over much of the land on which the sugar cane plantations stood. After an initial naval construction phase, opportunities to make a living on the island were increased to include not only fishing or subsistence farming, but also Naval jobs. Crops grown on the island include avocados, bananas, coconuts, grains, papayas and sweet potatoes. A number of permanent local jobs were provided by the US Navy, and their economy benefited. Starting in the 1970s General Electric had employed a few hundred workers at a manufacturing plant but that plant subsequently closed. Unemployment was widespread, with consequent social problems. The 2000 US census reported a median household income in 1999 dollars of $9,331 (compared to $41,994 for the US as a whole), and 35.8% of the population of 16 years and over in the labor force (compared to 63.9% for the US as a whole).[58]

Following the 2003 departure of the US Navy, the frail economy of the island was left in shambles, and efforts had to be made to redevelop the island's agricultural economy, clean up contaminated areas of the former bombing ranges, and to develop Vieques as a tourist destination. The Navy cleanup is now the island's largest employer, and has contributed over $20 million to the local economy over the last five years through salaries, housing, vehicles, taxes, and services. The Navy has provided specialized training to several local islanders.

Tourism

editFor sixty years the majority of Vieques was closed off by the US Navy, and the island remained almost entirely undeveloped for tourism. This lack of development is now marketed as a key attraction. Vieques is promoted under an ecotourism banner as a sleepy, unspoiled island of rural bucolic charm and pristine deserted beaches, and is rapidly becoming a popular destination.

Since the Navy's departure, tensions on the island have been low, although land speculation by foreign developers and fears of overdevelopment have caused some resentment among local residents, and there are occasional reports of lingering anti-American sentiment.[60]

The lands previously owned by the Navy have been turned over to the U.S. National Fish and Wildlife Service and the authorities of Puerto Rico and Vieques for management. The immediate bombing range area on the eastern tip of the island suffers from severe contamination, but the remaining areas are mostly open to the public, including many beautiful beaches that were inaccessible to civilians while the military was conducting training maneuvers.

Snorkeling is excellent, especially at Blue Beach (Bahía de la Chiva). Aside from archeological sites, such as La Hueca, and deserted beaches, a unique feature of Vieques is the presence of two pristine bioluminescent bays, including Mosquito Bay. Vieques is also famous for its paso fino horses, which are owned by locals and left to roam free over parts of the island.[60][61]

In 2011, TripAdvisor listed Vieques among the Top 25 Beaches in the World, writing "If you prefer your beaches without the accompanying commercial developments, Isla de Vieques is your tanning turf, with more than 40 beaches and not one traffic light."[62]

As of summer 2020, travel to the island was restricted due to the COVID-19 outbreak.[63]

Landmarks and places of interest

edit- Fortín Conde de Mirasol (Count Mirasol Fort), a fort built by the Spanish in the mid 19th century, now a museum

- Playa Esperanza (Esperanza Beach)

- The tomb of Le Guillou, the town founder, in Isabel Segunda

- La Casa Alcaldía (City Hall)

- Faro Punta Mulas, built in 1896

- Faro de Puerto Ferro

- Sun Bay Beach[64]

- The Bioluminescent Bay

- The 300-year-old ceiba tree

- Rompeolas (Mosquito Pier), renamed Puerto de la Libertad David Sanes Rodríguez in 2003

- Puerto Ferro Archaeological Site

- Black Sand Beach (Playa Negra)

- Hacienda Playa Grande (Old Sugarcane Plantation Building)

- Underground U.S. Navy Bunkers[65]

- Wreckage of the World War II Navy Destroyer USS Killen (DD-593)

Culture

editFestivals and events

editVieques celebrates its patron saint festival in July. The Fiestas Patronales de Nuestra Señora del Carmen is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[41][66]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Vieques include:

- Three Kings Festival – (or Epiphany Festival) – January 6

- Festival Cultural Viequense (Vieques Cultural Festival) – June

- Festival de la Arepa – August/September

Symbols

editThe municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[67]

Flag

editThe Vieques flag, approved in 1975, contains a representation of the municipal coat of arms and maintains its same symbolism. It consists of seven horizontal straight stripes, of equal width, four white and three blue, alternated. In its center is a green rhombus where a simplified design of the castle appears in yellow. The naval crown seen on the coat of arms is omitted from the flag.[68]

Coat of arms

editOn a barry shield with silver and blue waves is a green rhombus with a gold castle and on top is a golden crown with silver sails. The silver and blue waves symbolize the sea around Vieques. In the green rhombus is a historic Vieques fort represented by the traditional Spanish heraldic castle.[68]

Transportation

editVieques is served by Antonio Rivera Rodríguez Airport, which currently accommodates only small propeller-driven aircraft. Services to the island run from San Juan's Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, Isla Grande Airport (20- to 30-minute flights) and from Ceiba Airport (5-minute flights) and to Culebra. Flights are also available between Vieques and Saint Croix, Tortola, Virgin Gorda and Saint Thomas.

Also, a ferry runs from Ceiba several times a day. The ferry service is administered by the Autoridad de Transporte Marítimo (ATM) in Puerto Rico.[69] In 2019, governor Wanda Vázquez Garced said she would address the troubled, inconsistent ferry service between the islands and Ceiba.[70]

There are 13 bridges in Vieques, none of them distinguished.[71]

Public health

editThis article needs to be updated. (July 2022) |

There have been claims linking Vieques' higher cancer rate[72] to the long history of weapons testing on the island.

Nayda Figueroa, an epidemiologist for Puerto Rico's Cancer Registry, stated that research showed Vieques' cancer rate from 1995 to 1999 was 31 percent higher than for the main island. Michael Thun, head of epidemiological research at the American Cancer Society, cautioned that the variations in the rates could be attributed to chance, given the small population on Vieques.[73] A 2000 Nuclear Regulatory Commission report concluded that "the public had not been exposed to depleted uranium contamination above normal background (naturally occurring) levels".[74]

Surveys of the wreckage of a target ship in a shallow bay at the bombing range, however, revealed its identity to be that of the USS Killen, a target ship in nuclear tests in the Pacific in 1958. By 2002, it was evident that thousands of tons of steel that had originally been irradiated in the 1958 nuclear tests was missing from the wreckage in the bay. That steel has been missing for over 35 years and is still unaccounted for by the US Navy, Environmental Protection Agency and US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Hundreds of steel drums of unknown origin were found among the wreckage. Their identity and contents have not been adequately verified.[citation needed]

In response to concerns about potential contamination from toxic metals and other chemicals, the ATSDR conducted a number of surveys in 1999–2002 to test Vieques' soil, water supply, air, fish and shellfish for harmful substances. The general conclusion of the ATSDR survey was that no public health hazard existed as a result of the Navy's activities.[74] However, scientists have pointed out that fish samples were drawn from local markets, which often import fish from other areas. Also sample sizes from each location were too small to provide compelling evidence for the lack of a public health danger (Wargo, Green Intelligence). The conclusions of the ATSDR report have more recently, as of 2009[update], been questioned and discredited. A review is underway.[75][76][77]

Casa Pueblo, a Puerto Rican environmental group, reported "a series of studies pertaining to the flora and fauna of Vieques that clearly demonstrates sequestration of high levels of toxic elements in plant and animal tissue samples. Consequently, the ecological food web of the Vieques Island has been adversely impacted."[78]

Notable people

edit- Jaime Rexach Benitez, educator, politician and humanist;

- Susana Centeno, nurse, public servant

- Nelson Dieppa, professional boxer;

- Juan Francisco Luis, Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands (1978–1987);

- Germán Rieckehoff Sampayo, was president of the Puerto Rican Olympic committee;

- Carlos Vélez Rieckehoff, local nationalist leader and political activist;

- David Sanes Rodríguez, civilian killed by the US Navy in a live-fire bombing practice, his death sparked protests that culminated in the US Navy leaving the island.

Gallery

edit-

300-year-old Ceiba Tree in Isabel II

-

Sun Bay Beach

-

A view of Tobarrios Navío Beach from a nearby sea cave

-

A view from the Malecón (promenade) in Esperanza tobarrios of Cayo de Afuera

-

Playa Caracas (Red Beach)

-

Navío Beach

-

Festival Viequense (2007)

-

Esperanza Beach

-

Isabella II, Vieques

-

Fort Count of Mirasol

-

Playa Grande Sugar Plantation

-

Playa Negra, a black sand beach

-

Playa Negra and cliffs

-

Wild horses on Playa Negra

-

Esperanza

-

Aerial view from East

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Vieques Island". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "2000 Decennial Profiles: Vieques Municipio, Puerto Rico" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. May 2001. p. 76. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2011 – via Welcome.toPuertoRico.org.

- ^ Canedy, Dana (May 2, 2003). "Navy Leaves a Battered Island, and Puerto Ricans Cheer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Puerto Rico cleanup by U.S. military will take more than a decade". NBC. Associated Press. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "The 50 best beaches in the world". The Guardian. February 16, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Current Research". American Antiquity. 57 (1): 146–163. January 1992. doi:10.1017/S0002731600051222. S2CID 245677814.

- ^ Cinquino, Michael A.; Tronolone, Carmine A.; Vandrei, Charles & Vescelius, Gary S. (1997). "Historic Resources on the Vieques Naval Reservation and the Historical Development of Vieques Island, Puerto Rico" (PDF). Proceedings of the 17th Congress for Caribbean Archaeology: 376–387. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2019 – via University of Florida Digital Collections.

- ^ Mullenneaux, Lisa (2000). Ni Una Bomba Más!: Vieques vs. U.S. Navy. New York: Penington Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-97042-960-5.

- ^ Keeling, Stephen (2008). The Rough Guide to Puerto Rico. Rough Guides. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-85828-354-8. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ a b "Milestones". Vieques Insider. October 27, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office (in Spanish). Imprenta del gobierno. p. 164. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ "Vieques Island". Vieques Island. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Hulme, Peter (Winter 1987). "Islands of Enchantment". New Formations: A Journal of Culture, Theory & Politics. 3.

- ^ "Historia de Vieques". Archived from the original on February 22, 2015.

- ^ Ayala, César (Spring 2001). "From Sugar Plantations to Military Bases: the U.S. Navy's Expropriations in Vieques, Puerto Rico, 1940–45" (PDF). Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. 13 (1): 22–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2019 – via Department of Sociology, UCLA.

- ^ a b "Vieques tiene historia". ufdc.ufl.edu. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ "Rioz Castro: Vieques y la diaspora" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Contaminación en Vieques" (PDF).

- ^ Bosque-Pérez, Ramón; Morera, José Javier Colón, eds. (June 2006). Puerto Rico under Colonial Rule: Political Persecution And The Quest For Human Rights. New York: SUNY Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7914-6417-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ "On this date: "Five years ago..."". Northwest Herald. April 27, 2006. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (April 29, 2001). "Tiny Island Turns Into a Symbol of Discontent". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, James (October 18, 1999). "Vieques vigil a quagmire: U.S. pressed on whether to close Navy range". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2019 – via Latin American Studies.org.

- ^ "Newest Kennedy A Vieques Namesake". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. July 28, 2001. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019.

- ^ Defense Cleanup: Efforts at Former Military Sites on Vieques and Culebra, Puerto Rico, Are Expected to Continue through 2032 (PDF) (Report). United States Government Accountability Office. March 26, 2021. p. 15-16. GAO-21-268. Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ Weir, Bill (September 28, 2017). "Islanders cut off from world: 'We've lost everything'". CNN. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Mazzei, Patricia (April 7, 2019). "Hunger and an 'Abandoned' Hospital: Puerto Rico Waits as Washington Bickers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Uria, Daniel (January 21, 2020). "FEMA approves funds to rebuild hospital on Puerto Rican island". UPI. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Acevedo, Nicole (January 31, 2021). "Family of teen who died in Vieques, with no hospital since hurricane, sues Puerto Rico officials". NBC News. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Journal, Maricarmen Rivera Sánchez, The Weekly. "Gov't: Vieques to Have New Hospital by Mid-2024". The Weekly Journal. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "BNamericas - Puerto Rico puts out to tender new hospital ..." BNamericas.com. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Elecciones Generales 2024: Escrutinio General Archived 2024-12-30 at elecciones2024.ceepur.org (Error: unknown archive URL) on CEEPUR

- ^ Law, Gwillim (May 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ "Total Population: Florida barrio, Vieques Municipio, Puerto Rico". American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997–2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997–2004 (Primera edición ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ a b "Vieques Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ McCaffrey, Katherine T. (2009). "Environmental Struggle After the Cold War: New Forms of Resistance to the U.S. Military in Vieques, Puerto Rico". In Lutz, Catherine (ed.). Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle Against U.S. Military Posts. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-81475-243-2.

- ^ "Brightest bioluminescent bay". Guinness World Records. 2006.

- ^ Usup, Gires; Azanza, Rhodora V. (1998). "Physiology and dynamics of the tropical dinoflagellate Pyrodinium bahamense". In Anderson, Donald M.; Cembella, Allan D.; Hallegraeff, Gustaaf M. (eds.). The Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms. NATO ASI Series G, Ecological sciences no. 41. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-3-54064-117-9.

- ^ Phlips, E. J.; Badylak, S.; Bledsoe, E.; Cichra, M. (2006). "Factors affecting the distribution of Pyrodinium bahamense var. bahamense in coastal waters of Florida". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 322: 99–115. Bibcode:2006MEPS..322...99P. doi:10.3354/meps322099.

- ^ "High-Energy Storms Shape Puerto Rico". U.S. Geological Survey. May 16, 1996. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Puerto Rican Island 'Still In Crisis Mode' 3 Months After Maria". National Public Radio. December 22, 2017. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "VIEQUES ISLAND, PUERTO RICO". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing, 2000 [United States]: Summary File 4, Puerto Rico". ICPSR Data Holdings. April 28, 2004. doi:10.3886/icpsr13563.v1. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Population of Vieques Municipio, Puerto Rico". American FactFinder. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin". American FactFinder. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Harold, Brent (January 7, 2007). "Unpretentious Vieques, an island in transition". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Not So Wild Horses of Vieques". Uncommon Caribbean. June 1, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "25 Best Beaches in the World – Travelers' Choice Abarrios". Trip Advisor. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ "Alcalde de Vieques reitera oposición a apertura del turismo". Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Sun Bay recibe Bandera Azul". DRD Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Programa de Parques Nacionales de Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ "Vieques Military Bunkers". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Festivales, Eventos y Actividades en Puerto Rico". Puerto Rico Hoteles y Paradores (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "VIEQUES". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "Passenger & Cargo Ferry Guide, Vieques & Fajardo, Puerto Rico". Vieques.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ "Grave la flota que sirve a las islas municipio". El Nuevo Dia (in Spanish). August 25, 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ "Vieques Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Villerrael, Sandra Ivelisse (May 11, 2003). "Rullan: Studies on Cancer in Vieques Reflect Increase". Puerto Rico Herald. Vol. 7, no. 20. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Novak, Shannon (May 7, 2004). "Vieques Cancer Rate an Issue". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ a b "Soil Pathway Evaluation, Isla de Vieques Bombing Range". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Navarro, Mireya (August 6, 2009). "New Battle on Vieques, Over Navy's Cleanup of Munitions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Navarro, Mireya (November 13, 2009). "Navy's Vieques Training May Be Tied to Health Risks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Navarro, Mireya (November 29, 2009). "Reversal Haunts Federal Health Agency". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Casa Pueblo report: Summary of Findings". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

External links

edit- Vieques, Puerto Rico on Facebook

- Topographic map of Vieques in the Library of Congress archives

- Vieques, Puerto Rico: ATSDR Documents Dealing with the Isla de Vieques Bombing Range

- Welcome to Puerto Rico! Vieques

- Archivo Histórico de Vieques Collection hosted in the Digital Library of the Caribbean

- Diaspora Project DH Center at UPR-RP Collection hosted in the Digital Library of the Caribbean