Michael Francis Stean (born 4 September 1953) is an English chess grandmaster, an author of chess books and a tax accountant.

Michael Stean | |

|---|---|

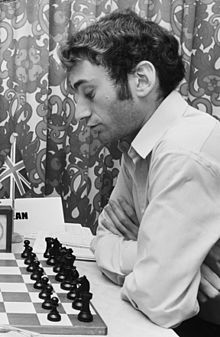

Stean at the Amsterdam Zonal 1978 | |

| Full name | Michael Francis Stean |

| Country | England |

| Born | 4 September 1953 London, England |

| Title | Grandmaster (1977) |

| Peak rating | 2540 (January 1979) |

| Peak ranking | No. 46 (January 1979) |

Early life and junior career

editStean was born on 4 September 1953 in London. He learned to play chess before the age of five, developing a promising talent that led to junior honours, including the London under-14 and British under-16 titles.

There was more progress in 1971, when he placed third at a junior event in Norwich (behind Sax and Tarjan, two other young players with bright futures). By 1973, he was able to top a tournament in Canterbury (ahead of Adorjan) and speculation began to grow that England had another potential runner in the race to become the country's first grandmaster. Fellow contenders were Ray Keene, whom Stean knew from Cambridge University and Tony Miles, who ultimately took the accolade. 1973 was also the year when Stean entered the (Teesside) World Junior Chess Championship and finished third behind Miles and tournament victor Alexander Beliavsky (ahead of Larry Christiansen). Curiously, both Stean and Miles defeated Beliavsky, but couldn't match his ruthlessness in dispatching inferior opposition.

Chess career

editDomestically, he was a joint winner of the British Chess Championship in 1974, but lost the play-off to George Botterill. In the first of his five Chess Olympiads at Nice in 1974, he won the prize for best game of the Olympiad, for his effort against Walter Browne. His next Olympiad was even more of a success; individual gold and team bronze medals at Haifa 1976. His performances in these events never resulted in a score of less than 50%.

International Master and International Grandmaster titles were awarded in 1975 and 1977 respectively.

In London in 1977, Stean lost a blitz game to a computer program (CHESS 4.6), making him the first grandmaster to lose a game to a computer. The moves, with Stean playing black, were: 1.e4 b6 2.d4 B♭7 3.Nc3 c5 4.dxc5 bxc5 5.Be3 d6 6.Bb5+ Nd7 7.Nf3 e6 8.O-O a6 9.Bxd7+ Qxd7 10.Qd3 Ne7 11.Rad1 Rd8 12.Qc4 Ng6 13.Rfe1 Be7 14.Qb3 Qc6 15.Kh1 O-O 16.Bg5 Ba8 17.Bxe7 Nxe7 18.a4 Rb8 19.Qa2 Rb4 20.b3 f5 21.Ng5 fxe4 22.Ncxe4 Rxf2 23.Rxd6 Qxd6 24.Nxd6 Rxg2 25.Nge4 Rg4 26.c4 Nf5 27.h3 Ng3+ 28.Kh2 Rxe4 29.Qf2 h6 30.Nxe4 Nxe4 31.Qf3 Rb8 32.Rxe4 Rf8 33.Qg4 Bxe4 34.Qxe6+ Kh8 35.Qxe4 Rf6 36.Qe5 Rb6 37.Qxc5 Rxb3 38.Qc8+ Kh7 39.Qxa6 1–0. [1] After 27 h3, Stean exclaimed, "This computer is a genius!"[2]

In international tournaments, he competed successfully at Montilla 1976 (2nd= with Kavalek and Calvo after Karpov), Montilla 1977 (3rd after Gligorić and Kavalek), London 1977 (2nd= with Mestel and Quinteros after Hort), Vršac 1979 (1st), Smederevska Palanka 1980 (1st) and Beersheba 1982 (1st).

During this period, Stean frequently had to put aside his own playing ambitions, as he was engaged as one of Viktor Korchnoi's team of seconds for world championship campaigns in 1977–78 and 1980–81. In many respects, the partnerships that developed were reasonably successful; Korchnoi brushed aside some powerful rival Candidates like Boris Spassky, Robert Hübner and Lev Polugaevsky en route to his two finals with Karpov. Stean's role was mostly involved with opening preparation and he and Korchnoi became good friends.

Writing

editWhile playing chess, he wrote two books – Sicilian Najdorf (Batsford, 1976) and Simple Chess (Faber, 1978). Both books were well received and the latter has become known as a chess classic,[3] remaining in print many years later (reprinted algebraic edition – Dover, 2003). Simple Chess concentrates on simple positional ideas and strategies and shows how they might be developed with the aid of sample games. He also contributed a lengthy introduction to Bent Larsen's book about the 1978 World Championship.

Stean was a chess columnist for The Observer between 1979 and 1993.[4]

- Stean, Michael (1976). Sicilian, Najdorf. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0098-6.

- Stean, Michael (2003). Simple Chess. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42420-0.

Retirement from chess

editIn 1982, at the age of 29 and more or less in his chess playing prime, Michael Stean retired from chess to become a tax accountant; a decision he does not appear to have regretted, as there has been no attempted return to playing chess in subsequent years. He joined tax consultants Casson Beckman early in 1984.[5]

Stean did however serve for a while as the manager of Nigel Short.[6]

Notable game

edit| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

- Stean-Browne, 1-0, Nice Olympiad 1974, Sicilian Najdorf – The game that won Stean the Turover Prize for 'best game' of the 1974 Olympiad.

References

edit- ^ David Levy, "Letter From Europe", Chess Life and Review, Dec. 1977

- ^ 1978: Runkel on computer chess, Chessbase, 7/28/2019

- ^ Michael Adams wins the Staunton Memorial, Chessbase, 21 August 2007

- ^ "Chess". Observer Magazine. London. 17 October 1993. p. 44 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Chess Magazine, February 1984, p. 242.

- ^ "Nigel Comes up Short Again in Game 8". Associated Press.

External links

edit- Michael Stean rating card at FIDE

- Hooper, David and Whyld, Kenneth (1984). The Oxford Companion to Chess. Oxford University. ISBN 0-19-217540-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Golombek, Harry, ed. (1981). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Chess. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-046452-8.

- Michael Francis Stean Chess Olympiad record at OlimpBase.org

- Michael Francis Stean player profile and games at Chessgames.com