A Mi Shebeirach[he 1] is a Jewish prayer used to request a blessing from God. Dating to the 10th or 11th century CE, Mi Shebeirach prayers are used for a wide variety of purposes. Originally in Hebrew but sometimes recited in the vernacular, different versions at different times have been among the prayers most popular with congregants. In contemporary Judaism, a Mi Shebeirach serves as the main prayer of healing, particularly among liberal Jews,[b] to whose rituals it has become central.

The original Mi Shebeirach, a Shabbat prayer for a blessing for the whole congregation, originated in Babylonia as part of or alongside the Yekum Purkan prayers. Its format—invoking God in the name of the patriarchs (and in some modern settings the matriarchs) and then making a case that a specific person or group should be blessed—became a popular template for other prayers, including that for a person called to the Torah and those for life events such as brit milah (circumcision) and b'nai mitzvah. The Mi Shebeirach for olim (those called to the Torah) was for a time the central part of the Torah service for less educated European Jews.

Since the late medieval period, Jews have used a Mi Shebeirach as a prayer of healing. Reform Jews abolished this practice in the 1800s as their conception of healing shifted to be more based in science, but the devastation of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s saw a re-emergence in gay and lesbian synagogues. Debbie Friedman's Hebrew–English version of the prayer, which she and her then-partner, Rabbi Drorah Setel,[13] wrote in 1987, has become the best-known setting. Released in 1989 on the album And You Shall Be a Blessing and spread through performances at Jewish conferences, the song became Friedman's best-known work and led to the Mi Shebeirach for healing not only being reintroduced to liberal Jewish liturgy but becoming one of the movement's central prayers. Many congregations maintain "Mi Shebeirach lists" of those to pray for, and it is common for Jews to have themselves added to them in anticipation of a medical procedure; the prayer is likewise widely used in Jewish hospital chaplaincy. Friedman and Setel's version and others like it, born of a time when HIV was almost always fatal, emphasize spiritual renewal rather than just physical rehabilitation, a distinction stressed in turn by liberal Jewish scholars.

For the congregation

edit| Hebrew (Ashkenazic rite)[he 2] | English translation[14] |

|---|---|

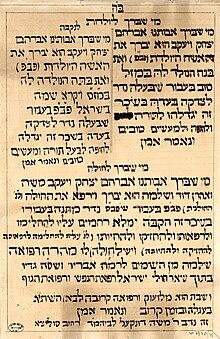

מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַעֲקֹב הוּא יְבָרֵךְ אֶת-כָּל-הַקָּהָל הַקָּדוֹשׁ הַזֶּה עִם כָּל-קְהִלּוֹת הַקֹּֽדֶשׁ. הֵם וּנְשֵׁיהֶם וּבְנֵיהֶם וּבְנוֹתֵיהֶם וְכָל אֲשֶׁר לָהֶם. וּמִי שֶׁמְּיַחֲדִים בָּתֵּי כְנֵסִיּוֹת לִתְפִלָּה. וּמִי שֶׁבָּאִים בְּתוֹכָם לְהִתְפַּלֵּל. וּמִי שֶׁנּוֹתְנִים נֵר לַמָּאוֹר וְיַֽיִן לְקִדּוּשׁ וּלְהַבְדָּלָה וּפַת לָאוֹרְ֒חִים וּצְדָקָה לָעֲנִיִּים. וְכָל מִי שֶׁעוֹסְ֒קִים בְּצָרְכֵי צִבּוּר בֶּאֱמוּנָה. הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא יְשַׁלֵּם שְׂכָרָם וְיָסִיר מֵהֶם כָּל-מַחֲלָה וְיִרְפָּא לְכָל-גּוּפָם. וְיִסְלַח לְכָל-עֲוֹנָם. וְיִשְׁלַח בְּרָכָה וְהַצְלָחָה. בְּכָל מַעֲשֵׂה יְדֵיהֶם. עִם כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲחֵיהֶם. וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן:

|

May he who blessed our fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,[a] bless all this holy congregation, together with all other holy congregations: them, their wives, their sons and daughters, and all that belong to them; those also who unite to form Synagogues for prayer, and those who enter therein to pray; those who give the lamps for lighting, and wine for Kiddush and Habdalah, bread to the wayfarers, and charity to the poor, and all such as occupy themselves in faithfulness with the wants of the congregation. May the Holy One, blessed be he, give them their recompense; may he remove from them all sickness, heal all their body, forgive all their iniquity, and send blessing and prosperity upon all the work of their hands, as well as upon all Israel, their brethren; and let us say, Amen. |

In the context of Ashkenazi liturgy, the traditional Mi Shebeirach has been described as either the third Yekum Purkan prayer[16] or as an additional prayer recited after the two Yekum Purkan prayers.[1] The three prayers date to Babylonia in the 10th or 11th century CE,[17] with the Mi Shebeirach—a Hebrew prayer—being a later addition to the other two, which are in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.[18] It is derived from a prayer for rain, sharing a logic that as God has previously done a particular thing, so he will again.[19] It is mentioned in the Machzor Vitry, in the writings of David Abudarham, and in Kol Bo.[18]

Both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews traditionally recite the prayer on Shabbat immediately after the haftara during the Torah service; Sephardic Jews also recite it on Yom Kippur,[18] althoug there are textual variants between the Ashkenazic and Sephardic version.[20] The Mi Shebeirach is often recited in the vernacular language of a congregation rather than in Hebrew. In Jewish Worship (1971), Abraham Ezra Millgram says that this is because of the prayer's "direct appeal to the worshipers and the ethical responsibilities it spells out for the people".[21] Traditionally the Mi Shebeirach for the congregation is set to a melody using a heptatonic scale that is in turn called the misheberak scale.[22]

Specialized versions

edit| Hebrew[he 3] | English translation[23] |

|---|---|

מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ, אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַֽעֲקֹב, מֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן, דָּוִד וּשְׁלֹמֹה, הוּא יְבָרֵךְ אֶת הָאִשָּׁה הַיּוֹלֶֽדֶת ___ וְאֶת בִּתָּהּ שֶׁנּוֹלְדָה לָהּ; וְיִקָּרֵא שְׁמָהּ בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל ___ וְיִזְכּוּ אָבִיהָ וְאִמָּהּ לְגַדְּלָהּ לְחֻפָּה וּלְמַעֲשִׂים טוֹבִים; וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן.

|

He who blessed our fathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Moses and Aaron, David and Solomon,[a] may he bless the mother ___ and her new-born daughter, whose name in Israel shall be ___. May they raise her for the marriage canopy and for a life of good deeds; and let us say, Amen. |

The Mi Shebeirach also came to serve as a template for prayers for specific blessings,[24] and for a time was sometimes prefixed with "Yehi ratzon" ('May it be your will').[25] Gregg Drinkwater in American Jewish History identifies a five-part structure to such prayers: 1) "Mi shebeirach" and an invocation of the patriarchs; 2) the name of the person to bless; 3) the reason they should be blessed; 4) what is requested for the person; and 5) the community's response.[26] William Cutter writes in Sh'ma:[25]

There are Misheberach prayers for every kind of illness, and almost every kind of relationship; there are Misheberach prayers for people who refrain from gossip, for people who maintain responsible business ethics. There are Misheberach blessings for everyone in the community, but slanderers, gossips, and schlemiels are excluded.

Some Mi Shebeirach prayers are used for life events, including birth (for the mother), bar or bat mitzvah, brit milah (circumcision), or conversion or return from apostasy.[27] Several concern marriage: in anticipation thereof, for newlyweds, and for a 25th or 50th wedding anniversary.[28] Occasional Mi Shebeirach prayers include those for the Ten Days of Penitence, the Fast of Behav, and Kol Nidre (for Jerusalem). During the Khmelnytsky Uprising, Rabbi Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller originated the practice of saying a Mi Shebeirach for those who do not converse during prayer.[27] Some prayers exist for particular communities, such as one used in many communities for members of the Israel Defense Forces,[27] or several published by the Reform movement for LGBT Jews.[11]

For olim

edit| Hebrew[he 4] | English translation[30] |

|---|---|

מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ, אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַֽעֲקֹב, הוּא יְבָרֵךְ אֶת שֶׁעָלָה לִכְבוֹד הַמָּקוֹם, וְלִכְבוֹד הַתּוֹרָה ___ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא יִשְׁמְרֵֽהוּ וְיַצִּילֵֽהוּ מִכׇּל צָרָה וְצוּקָה וּמִכׇּל נֶֽגַע וּמַחֲלָה, וְיִשְׁלַח בְּרָכָה וְהַצְלָחָה בְּכׇל מַעֲשֵׂה יָדָיו עִם כׇּל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶחָיו; וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן.

|

He who blessed our fathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,[a] may he bless ___ who has come up to honor God and the Torah. May the Holy One, blessed be he, protect and deliver him from all distress and illness, and bless all his efforts with success among all Israel his brethren; and let us say, Amen. |

In many congregations, a Mi Shebeirach is recited for each individual oleh[he 5] (person called for an aliyah), a practice originating among the Jews of France or Germany, originally just in pilgrim festivals.[31] Historically, in exchange for a donation, an oleh could have a blessing said for someone else as well. The practice expanded to Sabbath services by the 1200s, in part because it served as a source of income, and in turn spread to other countries. In German communities, it is recited even during weekday Torah readings.[32] It thus became the most important part of the service for less educated Jews but also causing services to run long, at the expense of the Torah reading itself.[33] Some congregations recite a Mi Shebeirach for all olim collectively, a tradition dating at least to Rabbi Eliyahu Menachem in 13th century London.[34]

As a prayer of healing

edit| Hebrew[35][he 6] | English translation[23] |

|---|---|

מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ, אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַעֲקֹב, משֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן, דָּוִד וּשְׁלֹמֹה, הוּא יְבָרֵךְ וִירַפֵּא אֶת הַחוֹלָה ___. הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא יִמָּלֵא רַחֲמִים עָלֶיהָ לְהַחֲלִימָהּ וּלְרַפֹּאתָהּ, לְהַחֲזִיקָהּ וּלְהַחֲיוֹתָהּ, וְיִשְׁלַח לָהּ מְהֵרָה רְפוּאָה שְׁלֵמָה, רְפוּאַת הַנֶּֽפֶשׁ וּרְפוּאַת הַגּוּף; וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן.

|

He who blessed our fathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Moses and Aaron, David and Solomon,[a] may he heal ___ who is ill. May the Holy One, blessed be he, have mercy and speedily restore her to perfect health, both spiritual and physical; and let us say, Amen. |

Macy Nulman's Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer ties the tradition of blessing the sick back to Yoreh De'ah 335:10 [he].[18] While Jewish liturgical names usually refer to people patronymically ("[person's name], child of [father's name]"), a Mi Shebeirach for healing traditionally refers to the sick person by matronym ("[person's name], child of [mother's name]"). Kabbalists teach that this evokes more compassion from God, citing Psalms 86:16, "Turn to me and have mercy on me; ... and deliver the son of your maidservant".[36] Jews in the late medieval and early modern periods used a Mi Shebeirach to pray for the bodies and souls of those not present, while also praying directly for individuals' healing, as they believed all healing was through God's will.[37] A Mi Shebeirach does not, however, fulfill the mitzvah (commandment) of bikur cholim (visiting the sick).[38]

Influenced by German ideals, early Reform Jews in the United States saw healing as a matter for private, rather than communal prayer.[39] Prayer healing became less popular as medicine modernized, and many Reform Jews came to see healing as a purely scientific matter.[40] The Union Prayer Book, published in 1895 and last revised in 1940, lacked any Mi Shebeirach for healing, rather limiting itself to a single line praying to "comfort the sorrowing and cheer the silent sufferers".[41] While the 1975 Reform prayerbook Gates of Prayer was more flexible than its predecessor and restored some older practices, it also had no Mi Shebeirach for healing.[42]

After the AIDS crisis began in the United States in 1981, the Mi Shebeirach and other communal healing prayers began to re-emerge in Reform and other liberal Jewish communities, particularly at gay and lesbian synagogues. A few years into the pandemic, Congregation Sha'ar Zahav, a Reform congregation in San Francisco that used its own gender-neutral, gay-inclusive siddur (prayerbook), began a communal Mi Shebeirach written by Garry Koenigsburg and Rabbi Yoel Kahn,[c] praying to heal "all the ill amongst us, and all who have been touched by AIDS and related illness".[43] As there was at the time no effective treatment for HIV/AIDS, and Jewish tradition says that prayers should not be in vain (tefilat shav), Sha'ar Zahav's version emphasized spiritual healing as well as physical.[44] Around the same time, Rabbi Margaret Wenig, a gay rights activist, began including a Mi Shebeirach in services with her elderly congregation in New York City, although not framed just as a prayer for healing.[45] At the gay and lesbian synagogue Beth Chayim Chadashim in Los Angeles, a 1985 siddur supervised by Rabbi Janet Marder included several prayers for healing, including a Mi Shebeirach blessing the full congregation with health, success, and forgiveness.[46]

Friedman and Setel's version

edit| "Mi Shebeirach" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Debbie Friedman | |

| from the album And You Shall Be a Blessing | |

| Released | 1989 |

| Studio | Sounds Write Productions |

| Songwriter(s) | Friedman, Drorah Setel |

Debbie Friedman was part of a wave of Jewish folk singers that began in the 1960s. Throughout the 1980s, as she lost many friends to AIDS and separately several to cancer, she traveled across the country performing at sickbeds.[47] From 1984 to 1987, she lived with Rabbi Drorah Setel, then her romantic partner,[13] who worked with AIDS Project Los Angeles.[44]

Marcia "Marty" Cohn Spiegel, a Jewish feminist activist familiar with Mi Shebeirach as a prayer of healing from her Conservative background, asked the couple to write a version of the prayer. Like the Sha'ar Zahav Mi Shebeirach, Friedman and Setel's version emphasized spiritual healing in the face of a disease which most at the time were unlikely to survive.[48] Refuah shleima ('full healing') was defined as the renewal, rather than repair, of body and spirit.[49] Using a mix of Hebrew and English, a trend begun by Friedman in the 1970s,[50] the two chose to include the Jewish matriarchs as well as the patriarchs to "express the empowerment of those reciting and hearing the prayer".[51] After the initial "mi sheiberach avoteinu" ('May the one who blessed our fathers'), they added "makor habrachah l'imoteinu" ('source of blessing for our mothers'). The first two words come from Lekha Dodi; makor ('source'), while grammatically masculine, is often used in modern feminist liturgy to evoke childbirth. Friedman and Setel then reversed "avoteinu" and "imoteinu" in the second Hebrew verse in order to avoid gendering God.[50]

Friedman and Setel wrote the prayer in October 1987.[52] It was first used in a Simchat Hochmah (celebration of wisdom) service at Congregation Ner Tamid celebrating Cohn Spiegel's eldering, led by Setel, openly lesbian rabbi Sue Levi Elwell, and feminist liturgist Marcia Falk.[53] Friedman included the song on her albums And You Shall Be a Blessing (1989) and Renewal of Spirit (1995) and performed it at Jewish conferences including those of the Coalition for the Advancement of Jewish Education, through which it spread to Jewish communities across the United States.[54] "Mi Shebeirach" became Friedman's most popular song.[55] She performed it at almost every concert, prefacing it with "This is for you" before singing it once on her own and then once with the audience.[56]

Analysis

editBy specifying refuah shleima as healing of both body (refuat haguf) and spirit (refuat hanefesh)—a commonality across denominations—the Mi Shebeirach for healing emphasizes that both physical and mental illness ought to be treated. The prayer uses the Š-L-M root, the same used in the Hebrew word shalom ('peace').[57] While refuah in Hebrew refers to both healing and curing, the contemporary American Jewish context emphasizes the distinction between the two concepts, with the Mi Shebeirach a prayer of the former rather than the latter.[58] Nonetheless, Rabbi Julie Pelc Adler critiques the Mi Shebeirach as inapplicable to chronic illness and proposes a different prayer for such cases.[59] Liberal Jewish commentary on the Mi Shebeirach for healing often emphasizes that it is not a form of faith healing, that it seeks a spiritual rather than physical healing, and that healing is not sought only for those who are named.[60]

Friedman and Setel's setting has drawn particular praise, including for its bilingual nature, which makes it at once traditional and accessible. It is one of several Friedman pieces that have been called "musical midrash". Lyrically, through asking God to "help us find the courage to make our lives a blessing", it emphasizes the agency of the person praying. Its melody resembles that of a ballad; like the traditional nusach (chant) for the Mi Shebeirach for healing, it is set in a major key.[61] Drinkwater views the modern Mi Shebeirach for healing as providing a "fundamentally queer insight" and frames it as part of a transformation in Judaism away from "narratives of wholeness, purity, and perfection".[62]

Use

editThe Mi Shebeirach of healing was added to the Reform siddur Mishkan T'filah in 2007,[62] comprising a three-sentence blessing in Hebrew and English praying for a "complete renewal of body and spirit" for those who are ill, and the lyrics to Friedman and Setel's version.[63] By the time it was added, it had already become, according to Drinkwater, "ubiquitous in Reform settings ... and in many non-Reform settings throughout the world". Drinkwater casts it as "the emotional highlight of synagogue services for countless Jews".[62] Elyse Frishman, Mishkan T'filah's editor, described including it as a "crystal clear" choice and that Friedman's setting had already been "canonized".[64] The prayer is now seen as central to liberal Jewish[b] ritual.[65] In contemporary usage, to say "I'll say a Mi Shebeirach for you" generally refers to the Mi Shebeirach for healing.[57]

Starting in the 1990s, Flam and Kahn's idea of a healing service spread across the United States, with the Mi Shebeirach for healing at its core. In time this practice has diminished, as healing has been more incorporated into other aspects of Jewish life.[66] Many synagogues maintain "Mi Shebeirach lists" of names to read on Shabbat.[67] Some Jews include on preoperative checklists that they should be added to their congregations' Mi Shebeirach lists.[68] The lists also serve to make the community aware that someone is ill, which can be beneficial but can also present problems in cases of stigmatized illnesses.[69] In some congregations, congregants with ill loved ones line up and the rabbi says the prayer. In more liberal ones, the rabbi will ask congregants to list names, and the congregant will then sing either the traditional Mi Shebeirach for healing or Friedman and Setel's version.[67] Sometimes congregants wrap one another in tallitot (prayer shawls) or hold shawls above one another.[56]

Use of the Mi Shebeirach for mental illness or addiction is complicated by social stigma. Some may embrace the Mi Shebeirach as a chance to spread awareness in their community, while others may seek anonymity.[69] Essayist Stephen Fried has advocated for the Mi Shebeirach for healing as an opportunity for rabbis "to reinforce that mental illness and substance use disorders 'count' as medical conditions for which you can offer prayers of healing".[70]

The prayer is often used in Jewish chaplaincy.[71] A number of versions exist for specific roles and scenarios in healthcare.[72] Silverman, who conducted an ethnographic study of liberal Jews in Tucson,[68] recounts attending a cancer support group for Jewish women that closed with Friedman's version of the Mi Shebeirach, even though a number of the group's members had described themselves as being irreligious or not praying.[73] She found that while the Mi Shebeirach of healing resonated widely, many participants were unaware how new the Friedman version was.[74] As Friedman lay dying of pneumonia in 2011 after two decades of chronic illness,[75] many North American congregations sang her and Setel's "Mi Shebeirach".[76] Setel wrote in The Jewish Daily Forward that, while people's Mi Shebeirach prayers for Friedman "did not prevent Debbie's death, ... neither were they offered in vain".[77]

Notes

editGeneral

edit- ^ a b c d e All versions of the Mi Shebeirach begin by invoking the patriarchs. Some versions, like those used in the Reform siddur (prayerbook) Mishkan T'filah and its companion book B'Chol L'Vavka, also list the matriarchs, and may refer to God as "the one" rather than "he".[15]

- ^ a b Liberal Jews refers generally to those who are not Orthodox. The main liberal denominations are Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism, Reconstructionist Judaism, and Jewish Renewal.[12]

- ^ Not to be confused with the Chabad rabbi of the same name.

Regarding Hebrew

edit- ^ /miː ˈʃeɪbeɪˌrɑːx/ or /-ɑːk/. Hebrew: מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ (Tiberian: [mi ˈʃɛbeˌrax]; modern: [mi ˈʃebeˌʁaχ]). Literally 'He who blessed', often translated as 'May he who blessed [our fathers]'[1] or 'May the one who blessed [our ancestors]'[2] (brackets original).[a] Other romanizations include Mi She Berakh,[3] Mi She-Berakh,[4] Mi Shebayrakh,[5] Mi Sheberach,[6] Mi Sheberakh,[7] MiSheBerach,[8] Misheberach,[9] and Misheberakh.[10] Mi Shebeirach, as an incipit that ends with an adjective, is usually not pluralized, although Mi Shebeirachs (or variant) is sometimes used in English.[11]

- ^ Transliteration:

mi shebberach avoteinu avraham yitzchak veya'akov hu yevarech et-kol-hakkahal hakkadosh hazzeh im kol-kehillot hakkodesh. hem unesheihem uveneihem uvenoteihem vechol asher lahem. umi shemmeyachadim battei chenesiyyot litfillah. umi shebba'im betocham lehitpallel. umi shennotenim ner lamma'or veyayin lekiddush ulehavdalah ufat la'orechim utzedakah la'aniyyim. vechol mi she'osekim betzarechei tzibbur be'emunah. hakkadosh baruch hu yeshallem secharam veyasir mehem kol-machalah veyirpa lechol-gufam. veyislach lechol-avonam. veyishlach berachah vehatzlachah. bechol ma'aseh yedeihem. im kol yisra'el acheihem. venomar amen:

- ^ Transliteration:

mi shebberach avoteinu, avraham yitzchak veya'akov, mosheh ve'aharon, david ushelomoh, hu yevarech et ha'ishah hayyoledet ___ ve'et bittah shennoledah lah; veyikkare shemah beyisra'el ___ veyizku aviha ve'immah legaddelah lechuppah ulema'asim tovim; venomar amen.

- ^ Transliteration:

Feminine version:mi shebberach avoteinu, avraham yitzchak veya'akov, hu yevarech et she'alah lichvod hammakom, velichvod hattorah ___ hakkadosh baruch hu yishmerehu veyatzilehu mikkol tzarah vetzukah umikkol nega umachalah, veyishlach berachah vehatzlachah bechol ma'aseh yadav im kol yisra'el echav; venomar amen.

A nonbinary-inclusive version approved by Conservative Judaism's Rabbinical Assembly changes בַעֲבּוּר שֶׁעָלָה/שֶׁעָלְתָה (va'abbur she'alah/she'aletah 'because he/she has come up') to בַעֲבּוּר הַעֲלִיָה (va'abbur ha'aliyah 'because of this aliyah') and מִשְפַּחְתּוֹ/מִשְפַּחְתָה (mischpachto/mishpachtah, 'his/her family'—not included in Birnbaum's version) to הַמִשְפַּחָה (hamishpachah 'the family').[29]מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ, אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַֽעֲקֹב, הוּא יְבָרֵךְ אֶת שֶׁעָלְתָה לִכְבוֹד הַמָּקוֹם, וְלִכְבוֹד הַתּוֹרָה ___ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא יִשְׁמְרֵֽהוּ וְיַצִּילֵֽהוּ מִכׇּל צָרָה וְצוּקָה וּמִכׇּל נֶֽגַע וּמַחֲלָה, וְיִשְׁלַח בְּרָכָה וְהַצְלָחָה בְּכׇל מַעֲשֵׂה יָדָיו עִם כׇּל יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶחָיו; וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן.mi shebberach avoteinu, avraham yitzchak veya'akov, hu yevarech et she'aletah lichvod hammakom, velichvod hattorah ___ hakkadosh baruch hu yishmerehu veyatzilehu mikkol tzarah vetzukah umikkol nega umachalah, veyishlach berachah vehatzlachah bechol ma'aseh yadav im kol yisra'el echav; venomar amen.

- ^ Plural olim.

- ^ Transliteration:

Masculine version:mi shebberach avoteinu, avraham yitzchak veya'akov, mosheh ve'aharon, david ushelomoh, hu yevarech virappe et hacholah. hakkadosh baruch hu yimmale rachamim aleiha lehachalimah ulerappotah, lehachazikah ulehachayotah, veyishlach lah meherah refu'ah shelemah, refu'at hannefesh urefu'at hagguf; venomar amen

מִי שֶׁבֵּרַךְ אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ, אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיַעֲקֹב, משֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן, דָּוִד וּשְׁלֹמֹה, הוּא יְבָרֵךְ וִירַפֵּא אֶת הַחוֹלֶה ___. הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא יִמָּלֵא רַחֲמִים עָלָיו לְהַחֲלִימוֹ וּלְרַפֹּאתוֹ, לְהַחֲזִיקוֹ וּלְהַחֲיוֹתוֹ, וְיִשְׁלַח לוֹ מְהֵרָה רְפוּאָה שְׁלֵמָה, רְפוּאַת הַנֶּֽפֶשׁ וּרְפוּאַת הַגּוּף; וְנֹאמַר אָמֵן.mi shebberach avoteinu, avraham yitzchak veya'akov, mosheh ve'aharon, david ushelomoh, hu yevarech virappe et hacholeh ___. hakkadosh baruch hu yimmale rachamim alav lehachalimo ulerappoto, lehachaziko ulehachayoto, veyishlach lo meherah refu'ah shelemah, refu'at hannefesh urefu'at hagguf; venomar amen.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b Millgram 1971, p. 188.

- ^ Fields 2021.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004.

- ^ Millgram 1971.

- ^ Nulman 1993.

- ^ Silverman 2016.

- ^ Praglin 1999; Pelc Adler 2011.

- ^ Sered 2005.

- ^ Flam 1996, pp. 486–488; Silton et al. 2009; Cutter 2011a.

- ^ Flam 1996, p. 493; Cutter 2011b.

- ^ a b Eger 2020, § Mi Shebeirachs (Blessings after the Torah Reading), p. 91.

- ^ Silverman 2016, pp. 170, 173.

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2020.

- "Debbie Friedman and Rabbi Drorah Setel, two feminist innovators deeply connected to Judaism’s Reform Movement (and then romantic partners)" (p. 606).

- "Although active in lesbian feminist circles and well-known among those women as a lesbian, Debbie Friedman generally kept her sexual orientation private" (pp. 618–619).

- "The extent to which Debbie Friedman was or was not 'out' or 'in the closet' remains contested. After she died in 2011, some commentators who publicly described her as a lesbian were critiqued for 'outing' her posthumously, given Friedman's perceived preference in life to keep her sexuality private. But others, including close friends, argued that she was not really closeted, just guarded about her private life" (p. 619 n. 52), citing Tracy 2011 & Klein 2011.

- ^ Singer 1915, p. 218.

- ^ Frishman 2007, p. 252; Fields 2021.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, pp. 461-462.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, p. 461; Millgram 1971, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d Nulman 1993, p. 244.

- ^ Cutter 2011a, p. 5.

- ^ Compare the Sephardic version with the Ashkenazic version presented in the sidebar here.

- ^ Millgram 1971, p. 189.

- ^ Tsuji & Müller 2021, p. 97.

- ^ a b Birnbaum 1949, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, pp. 462–463.

- ^ a b Cutter 2011a, p. 5.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 612.

- ^ a b c Nulman 1993, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Nulman 1993, pp. 244–245; Eisenberg 2004, p. 463.

- ^ Austrian, Scheinberg & Silver 2022, pp. 9–10, 12; Hajdenberg 2022.

- ^ Masculine version from Birnbaum 1949, pp. 371–372. Feminine version slightly modified from the same, changing only gendered pronouns.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, pp. 462–463; Nulman 1993, p. 244; Elbogen 1913, p. 161.

- ^ Madrikh le-minhag Ashkenaz, page 25.

- ^ Elbogen 1913, p. 161.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, pp. 462–463; Nulman 1993, p. 244.

- ^ The text in Birnbaum. Other version differ substantially, see for example the version on Sefaria.

- ^ Eisenberg 2004, pp. 463, 755, citing Ps. 86:16 (Eisenberg's translation).

- ^ Praglin 1999, p. 11, citing Hertz 1948, p. 492.

- ^ Moss 2006, p. 369.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 613.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 609.

- ^ Sermer 2014, p. 78, quoting CCAR 1940, p. 148.

- ^ Sermer 2014, p. 79, referencing Stern 1975.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, pp. 613–616.

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2020, p. 617.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 615 n. 39.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, pp. 617–618.

- ^ Sermer 2014, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, pp. 618–620, citing Setel 2011.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 620; Setel 2011.

- ^ a b Sermer 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 620, quoting Setel 2011.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 606.

- ^ Sermer 2014, p. 81; Drinkwater 2020, p. 621.

- ^ Drinkwater 2020, p. 621, referencing Friedman & Setel 1989; Sermer 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Fox 2011. Sermer 2014, p. 87: "From among twenty albums worth of repertoire, journalists and bloggers repeatedly single out 'Mi Shebeirach' as [Friedman's] most famous and beloved piece."

- ^ a b Sermer 2014, p. 85.

- ^ a b Sermer 2014, p. 81.

- ^ Sered 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Pelc Adler 2011.

- "To pray for 'complete healing' for those whose ailments cannot or will not ever be completely 'healed' or 'cured' seems audacious and perhaps even offensive" (p. 278).

- Excerpt from the proposed prayer: "May God give to him/her grace, compassion, and lovingkindness; might to his/her hand, wisdom to his/her heart, and the strength to live a life of honor and peace" (p. 279).

- ^ Silverman 2016, p. 174, citing Cutter 2011a, Cutter 2011b, Pelc Adler 2011, and Sered 2005. Silverman notes that "a small number of" participants in her study "attributed physical improvements to the prayers that were said for them" (p. 181).

- ^ Sermer 2014, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c Drinkwater 2020, p. 628.

- ^ Friedman & Setel 2007.

- ^ Sermer 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Silverman 2016, p. 173, citing Cutter 2011a and Cutter 2011b.

- ^ Sermer 2014, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Silverman 2016, p. 173.

- ^ a b Silverman 2016, p. 175.

- ^ a b Silverman 2016, p. 177.

- ^ Fried 2016.

- ^ Sered 2005; Silton et al. 2009, pp. 152, 155.

- ^ Silverman 2016, p. 174. "Specific versions of the Mi Sheberach have been created for caregivers, health-care providers, those undergoing different types of procedures, and those living with chronic conditions."

- ^ Silverman 2016, p. 170.

- ^ Silverman 2016, pp. 180–181. "Often, the people I was interviewing knew only the modern version of the prayer, yet its historical resonance was still central to their reactions to it. Sarah, who had said the Mi Sheberach for her ill adult son told me [sic]: 'It's so powerful knowing that people have been saying these exact words for thousands of years.' When I pointed out that the version she was referring to was only 20 years old, she was baffled" (p. 181).

- ^ Fox 2011.

- ^ Sermer 2014, p. 87.

- ^ Setel 2011.

Sources

editLiturgical sources

edit- Birnbaum, Philip (1949). Daily Prayer Book: Ha-Siddur ha-Shalem (in English and Hebrew) – via Wikisource. [scan ] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Central Conference of American Rabbis, ed. (1940) [1895]. The Union Prayerbook for Jewish Worship (in English and Hebrew). Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.: Central Conference of American Rabbis. OL 24222786M.

- Eger, Denise L., ed. (2020). Mishkan Ga'avah: Where Pride Dwells. New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis. ISBN 978-0-88123-358-2.

- Frishman, Elyse D., ed. (2007). Mishkan T'filah: A Reform Siddur (PDF) (in English and Hebrew). New York City: CCAR Press. ISBN 978-0-88123-104-5. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022.

- Friedman, Debbie; Setel, Drorah (2007). "Prayers for Healing". p. 253.

- Fields, Harvey J. (2021) [1975]. "Mi Shebeirach". In Haber, Hilly; Grabiner, Sarah (eds.). B'Chol L'Vavcha: With All Your Heart: A Commentary on the Prayer Book (in English and Hebrew) (Third ed.). New York City: CCAR Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8812-3343-8.

- Friedman, Debbie (writer and performer); Setel, Drorah (writer) (1989). "Mi Shebeirach". And You Shall Be a Blessing (Album) (in English and Hebrew). Sounds Write Productions.

- Audio and lyrics: Central Conference of American Rabbis (2018). "Mi Shebeirach—Prayer for Healing". ReformJudaism.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- Singer, Simeon (1915) [1890]. The Standard Prayer Book: Authorized English Translation (in English and Hebrew) (Enlarged American ed.). New York City: Bloch – via Wikisource. [scan ] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Hertz, Joseph (1948) [1890]. The Authorized Daily Prayer Book (1948 ed.). New York City: Bloch.

- Stern, Chaim, ed. (1975). Gates of Prayer: The New Union Prayerbook (in English and Hebrew). Central Conference of American Rabbis. ISBN 978-0-916694-00-5. OL 22777594M.

Book and journal sources

edit- Cutter, William (1 June 2011a). "A Prayer for Healing: The Misheberach". Sh'ma: A Journal of Jewish Ideas. 41 (681): 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022 – via Berman Jewish Policy Archive.

- Cutter, William, ed. (2011b). Midrash & Medicine: Healing Body and Soul in the Jewish Interpretive Tradition. Woodstock, Vt., U.S.: Jewish Lights Publishing. ISBN 9781580234283. OL 24423640M.

- Pelc Adler, Julie (2011). "A Midrash on the Mi Sheberakh: A Prayer for Persisting". (registration required)

- Drinkwater, Gregg (2020). "Queer Healing: AIDS, Gay Synagogues, Lesbian Feminists, and the Origins of the Jewish Healing Movement". American Jewish History. 104 (4). American Jewish Historical Society / Johns Hopkins University Press: 605–629. doi:10.1353/ajh.2020.0053. S2CID 242611690. EBSCOhost 149410711.

- Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2004). "Yekum Purkan". JPS Guide to Jewish Traditions. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. pp. 461–463, 755. ISBN 0-8276-0760-1. Retrieved 9 December 2022 – via Open Library.

- Elbogen, Ismar (1913). Jewish Liturgy: A Comprehensive History. Translated by Scheindlin, Raymond P. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society (published 1993). ISBN 978-0827604452.

- Flam, Nancy (1996). "Healing the Spirit: A Jewish Approach". CrossCurrents. 46 (4). Association for Public Religion and Intellectual Life / University of North Carolina Press: 487–496. JSTOR 24460295.

- Millgram, Abraham Ezra (1971). "The Yekum Purkan Prayers". Jewish Worship. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 188–189. ISBN 0-8276-0003-8. OL 26837828M. Retrieved 9 December 2022 – via Open Library.

- Moss, Steven (2006). "Relating to the Sick and Dying". In Bloom, Jack H. (ed.). Jewish Relational Care A–Z: We Are Our Other's Keeper. New York City: Haworth Press. pp. 369–373. ISBN 9780789027061. OL 3399326M – via Open Library.

- Nulman, Macy (1993). "Mi Shebayrakh". The Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer: Ashkenazic and Sephardic Rites. Northvale, N.J., U.S.: Jason Aronson. pp. 243–245. ISBN 0876683707. OL 1729305M. Retrieved 9 December 2022 – via Open Library.

- Praglin, Laura J. (1999). "The Jewish Healing Tradition in Historical Perspective". The Reconstructionist. 63 (2): 6–15. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via ResearchGate.

- Sered, Susan S. (2005) [December 2004]. "Healing as Resistance: Reflections upon New Forms of American Jewish Healing". In Sered, Susan S.; Barnes, Linda L. (eds.). Religion and Healing in America. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 231–252. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195167962.003.0015. ISBN 9780199850150.

- Sermer, Tanya (2014). "Jewish Spiritual Healing, Mi Shebeirach, and the Legacy of Debbie Friedman". In Andrews, Gavin J.; Kingsbury, Paul; Kearns, Robin (eds.). Soundscapes of Wellbeing in Popular Music. London: Routledge (published 2016). pp. 77–81. doi:10.4324/9781315609997. ISBN 9781315609997. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- Silton, Nava R.; Asekoff, Cecille A.; Taylor, Bonita; Silton, Paul B. (30 November 2009). "Shema, Vidui, Yivarechecha: What to Say and How to Pray with Jewish Patients in Chaplaincy". Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. 16 (3–4). Association of Professional Chaplains / Taylor & Francis: 149–160. doi:10.1080/08854726.2010.492707. PMID 20658428. S2CID 43517374. EBSCOhost 105071354.

- Silverman, Gila (2016). "'I'll Say a Mi Sheberach for You': Prayer, Healing and Identity Among Liberal American Jews" (PDF). Contemporary Jewry. 36 (2). Association for the Social Scientific Study of Jewry / Springer: 169–185. doi:10.1007/s12397-016-9156-7. JSTOR 26345502. S2CID 147061325. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- Tsuji, Kinko; Müller, Stefan C. (2021). "Comparison with Non-European Systems". Physics and Music: Essential Connections and Illuminating Excursions. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 91–125. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68676-5_5. ISBN 978-3-030-68676-5. S2CID 236649611.

Other sources

edit- Austrian, Guy; Scheinberg, Robert; Silver, Deborah (25 May 2022). "Calling Non-binary People to Torah Honors" (PDF) (Teshuvah). Rabbinical Assembly. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Fox, Margalit (11 January 2011). "Debbie Friedman, Singer of Jewish Music, Dies at 59". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- Fried, Stephen (20 September 2016). "Jews Must Take Mental Illness Out of the Shadows". The Forward. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- Hajdenberg, Jackie (8 June 2022). "Non-gendered Language for Calling Jews to the Torah Gets Conservative Movement Approval". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Klein, Marc (4 February 2011). "Did Debbie Friedman Coverage Go Too Far: Coming Out Debate Is an Old One". J. The Jewish News of Northern California. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Setel, Drorah (19 January 2011). "Debbie Friedman's Healing Prayer". Opinion. The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- Tracy, Marc (13 January 2011). "Debbie Friedman in Full". Tablet. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.