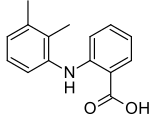

Mefenamic acid is a member of the anthranilic acid derivatives (or fenamate) class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and is used to treat mild to moderate pain.[4][5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ponstel, Ponstan, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681028 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, rectal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | >90% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (52–67%), faeces (20–25%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.467 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 241.290 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Its name derives from its systematic name, dimethylphenylaminobenzoic acid. It was discovered and brought to market by Parke-Davis as Ponstel in the 1960s. It became generic in the 1980s and is available worldwide under many brand names such as Meftal.[6]

Medical uses

editMefenamic acid is used to treat pain and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, postoperative pain, acute pain including muscle and back pain, toothache and menstrual pain, as well as being prescribed for menorrhagia.[7][8][9] In a 10-year study, mefenamic acid and other oral medicines (tranexamic acid) were as effective as the levonorgestrel intrauterine coil; the same proportion of women had not had surgery for heavy bleeding and had similar improvements in their quality of life.[10][11]

There is evidence that supports the use of mefenamic acid for perimenstrual migraine headache prophylaxis, with treatment starting two days prior to the onset of flow or one day prior to the expected onset of the headache and continuing for the duration of menstruation.[5]

Mefenamic acid is recommended to be taken with food.[12]

Contraindications

editMefenamic acid is contraindicated in people who have shown hypersensitivity reactions such as urticaria and asthma to this drug or to other NSAIDs (e.g. aspirin); those with peptic ulcers or chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract; those with kidney or liver disease; heart failure; after coronary artery bypass surgery; and during the third trimester of pregnancy.[8][13]

Side effects

editKnown mild side effects of mefenamic acid include headaches, nervousness, and vomiting. Potentially serious side effects may include diarrhea, gastrointestinal perforation, peptic ulcers, hematemesis (vomiting blood), skin reactions (rashes, itching, swelling; in rare cases toxic epidermal necrolysis) and rarely blood cell disorders such as agranulocytosis.[14][8] It has been associated with acute liver damage.[15]

In 2008 the US label was updated with a warning concerning a risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus in pregnancy.[16]

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the drug label to be updated for all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid.[17][18] They recommend avoiding NSAIDs in pregnant women at 20 weeks or later in pregnancy.[17][18]

In its November 2023 monthly drug safety alert under the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI), the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission flagged a risk of DRESS Syndrome due to use of mefenamic acid.[19]

Overdose

editSymptoms of overdosing include kidney failure, gastrointestinal problems, bleeding, rashes, confusion, hallucinations, vertigo, seizures, and loss of consciousness. It is treated with induction of vomiting, gastric lavage, bone char, and control of electrolytes and vital functions.[8]

Interactions

editInteractions are broadly similar to those of other NSAIDs. Mefenamic acid interferes with the anti–blood clotting mechanism of Aspirin. It increases the blood thinning effects of warfarin and phenprocoumon because it displaces them from their plasma protein binding and increases their free concentrations in the bloodstream. It adds to the risk of gastrointestinal ulcera associated with corticosteroids and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. It can increase the risk for adverse effects of methotrexate and lithium by lowering their excretion via the kidneys. It can increase the kidney toxicity of ciclosporin and tacrolimus. Combination with antihypertensive drugs such as ACE inhibitors, sartans and diuretics can decrease their effectiveness as well as increase the risk for kidney toxicity.[8][9]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

editLike other members of the anthranilic acid derivatives (or fenamate) class of NSAIDs, it inhibits both isoforms of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX-1 and COX-2). This prevents formation of prostaglandins,[15][20] which play a role in pain sensitivity, inflammation and fever, but also in hemostasis, kidney function, sustaining of pregnancy, and protection of the gastric mucosa.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

editMefenamic acid is rapidly absorbed from the gut and reaches highest concentrations in the blood plasma after one to four hours. When in the bloodstream, over 90% of the substance are bound to plasma proteins. It probably crosses the placenta, and is found in the breast milk in small amounts.[8][13]

It is metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP2C9 to the only weakly active 3'-hydroxymethylmefenamic acid. 3'-carboxymefenamic acid has also been identified as a metabolite, as well as carboxy glucuronides of all three substances. Mefenamic acid and its metabolites are excreted via the urine (52–67%) and the faeces (20–25%, or less than 20% following another source). The parent substance has a biological half-life of two hours; the half-life of its metabolites may be longer.[8][9][13]

History

editScientists led by Claude Winder from Parke-Davis invented mefenamic acid in 1961, along with fellow members of the class of anthranilic acid derivatives, flufenamic acid in 1963 and meclofenamate sodium in 1964.[22] U.S. Patent 3,138,636 on the drug was issued in 1964.[23][24]

It was approved in the UK in 1963 as Ponstan, in West Germany in 1964 as Ponalar and in France as Ponstyl, and the US in 1967 as Ponstel.[15][24]

Chemistry

editSynthesis

editAnalogous to fenamic acid, this compound may be made from 2-chlorobenzoic acid and 2,3-dimethylaniline.[25]

Conformational flexibility

editMefenamic acid, a member of the fenamate, is a chemical compound derived from anthranilic acid . This derivative is created by substituting one of the hydrogen atoms attached to the nitrogen atom with a 2,3-dimethylphenyl fragment. The result is a structurally complex molecule with fascinating conformational properties.

The mefenamic acid molecule exhibits conformational lability, meaning it can exist in various shapes or conformers. This flexibility arises from changes in the position of the carboxylic acid group and the 2,3-dimethylphenyl fragment about the anthranil moiety. Specifically, the arrangement of the substituted benzene fragments relative to each other plays a crucial role in determining the different polymorphic forms of mefenamic acid.[26]

Recent experimental studies have unveiled two additional hidden conformers of mefenamic acid.[27] These conformers result from alterations in the positions of hydroxyl groups within the molecule. This discovery adds to our understanding of the compound's structural diversity.

External factors, including temperature, pressure, and the surrounding medium, highly influence the conformational state of mefenamic acid. Researchers have conducted extensive investigations into its spatial structure not only in organic solvents[28] but also in supercritical fluids,[29][30] aerogels,[31] and lipid bilayers.[32][33] These studies have helped elucidate the impact of different environments on the molecule's conformation.

Society and culture

editAvailability and pricing

editMefenamic acid is generic and is available worldwide under many brand names.[6]

In the US, wholesale price of a week's supply of generic mefenamic acid has been quoted as $426.90 in 2014. Brand-name Ponstel is $571.70.[34] By contrast, in the UK, a weeks supply is £1.66, or £8.17 for branded Ponstan.[35] In New Zealand, a weeks's supply of Ponstan costs NZ$9.08, around US$5.50. [36]

Research

editWhile studies have been conducted to see if mefenamic acid can improve behavior in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease[37][38] there is little evidence that mefenamic acid or other NSAIDs can treat or prevent Alzheimer's in humans; clinical trials of NSAIDs other than mefenamic acid for treatment of Alzheimer's have found more harm than benefit.[39][40][41] A small controlled study of 28 human subjects showed improved cognitive impairment using mefenamic acid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy.[42]

References

edit- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. 6 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Ponstel Label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 19 February 2008.

- ^ a b Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D (April 2008). "Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review". Neurology. 70 (17): 1555–1563. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000310638.54698.36. PMID 18427072. S2CID 27966664.

- ^ a b "International listings for mefenamic acid". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Digital Medicines Information Suite". MedicinesComplete. doi:10.18578/bnf.855907230. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. 2020. Parkemed 500 mg-Filmtabletten.

- ^ a b c "mediQ: Mefenaminsäure". Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Kai J, Dutton B, Vinogradova Y, Hilken N, Gupta J, Daniels J (October 2023). "Rates of medical or surgical treatment for women with heavy menstrual bleeding: the ECLIPSE trial 10-year observational follow-up study". Health Technology Assessment. 27 (17): 1–50. doi:10.3310/JHSW0174. PMC 10641716. PMID 37924269.

- ^ "The coil and medicines are both effective long-term treatments for heavy periods". NIHR Evidence. 8 March 2024. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_62335.

- ^ "Side effects for Mefenamic Acid". Medline Plus. National Institutes of Health.

- ^ a b c Cerner Multum. "Mefenamic Acid". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- ^ Aronson JK (2010). eyler's Side Effects of Analgesics and Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-08-093294-1.

- ^ a b c "Mefenamic Acid". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. January 2020. PMID 31643361. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Safety Labeling Changes: Ponstel (mefenamic acid capsules, USP)". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 2008. Archived from the original on 4 November 2009.

- ^ a b "FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Monthly Drug Safety Alert". Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Prusakiewicz JJ, Duggan KC, Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ (August 2009). "Differential sensitivity and mechanism of inhibition of COX-2 oxygenation of arachidonic acid and 2-arachidonoylglycerol by ibuprofen and mefenamic acid". Biochemistry. 48 (31): 7353–7355. doi:10.1021/bi900999z. PMC 2720641. PMID 19603831.

- ^ Mutschler E (2013). Arzneimittelwirkungen. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart. pp. 205–206, 444. ISBN 978-3-8047-2898-1.

- ^ Whitehouse MW (2009). "Drugs to treat inflammation: a historical introduction". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 4 (25): 707–729 (718). doi:10.2174/092986705774462879. ISBN 978-1-60805-207-3. PMID 16378496.

- ^ US 3,138,636, Scherrer RA, issued 23 June 1964, assigned to Parke Davis and Co LLC

- ^ a b Sittig M (1988). "Mefenamic acid". Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (PDF). Vol. 1 (Second ed.). Noyes Publications. pp. 918–919. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-23.

- ^ Trinus FP, Mokhort NA, Yagupol'skii LM, Fadeicheva AG, Danilenko VS, Ryabukha TK, et al. (1977). "Mefenamic acid — A Nonsteroid Antiinflammatory Agent". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 11 (12): 1706–1711. doi:10.1007/BF00778304. S2CID 45211486.

- ^ SeethaLekshmi S, Guru Row TN (August 2012). "Conformational Polymorphism in a Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug, Mefenamic Acid". Crystal Growth & Design. 12 (8): 4283–4289. doi:10.1021/cg300812v. ISSN 1528-7483.

- ^ Belov KV, Batista de Carvalho LA, Dyshin AA, Efimov SV, Khodov IA (October 2022). "The Role of Hidden Conformers in Determination of Conformational Preferences of Mefenamic Acid by NOESY Spectroscopy". Pharmaceutics. 14 (11): 2276. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14112276. PMC 9696638. PMID 36365095.

- ^ Khodov IA, Belov KV, Efimov SV, de Carvalho LA (January 2019). Determination of preferred conformations of mefenamic acid in DMSO by NMR spectroscopy and GIAO calculation. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 2063. AIP Publishing. p. 040007. doi:10.1063/1.5087339.

- ^ Belov KV, Batista de Carvalho LA, Dyshin AA, Kiselev MG, Sobornova VV, Khodov IA (December 2022). "Conformational Analysis of Mefenamic Acid in scCO2-DMSO by the 2D NOESY Method". Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 16 (7): 1191–1199. Bibcode:2022RJPCB..16.1191B. doi:10.1134/S1990793122070028. ISSN 1990-7931. S2CID 256259116.

- ^ Khodov I, Sobornova V, Mulloyarova V, Belov K, Dyshin A, de Carvalho LB, et al. (August 2023). "Does DMSO affect the conformational changes of drug molecules in supercritical CO2 Media?". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 384: 122230. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122230. S2CID 259822531.

- ^ Khodov I, Sobornova V, Mulloyarova V, Belov K, Dyshin A, de Carvalho LB, et al. (April 2023). "Exploring the Conformational Equilibrium of Mefenamic Acid Released from Silica Aerogels via NMR Analysis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (8): 6882. doi:10.3390/ijms24086882. PMC 10138679. PMID 37108046.

- ^ Khodov IA, Musabirova GS, Klochkov VV, Karataeva FK, Huster D, Scheidt HA (December 2022). "Structural details on the interaction of fenamates with lipid membranes". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 367: 120502. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120502. S2CID 252747244.

- ^ Khodov IA, Belov KV, Huster D, Scheidt HA (June 2023). "Conformational State of Fenamates at the Membrane Interface: A MAS NOESY Study". Membranes. 13 (6): 607. doi:10.3390/membranes13060607. PMC 10300900. PMID 37367811.

- ^ "Drugs for Osteoarthritis". The Medical Letter. 56 (1450): 80–84. September 2014. PMID 25157683.

- ^ "Access leading drug and healthcare references". www.medicinescomplete.com. Retrieved 19 September 2014..

- ^ "PHARMAC Schedule Online". schedule.pharmac.govt.nz. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Joo Y, Kim HS, Woo RS, Park CH, Shin KY, Lee JP, et al. (January 2006). "Mefenamic acid shows neuroprotective effects and improves cognitive impairment in in vitro and in vivo Alzheimer's disease models". Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1124/mol.105.015206. PMID 16223958. S2CID 20982844.

- ^ Daniels MJ, Rivers-Auty J, Schilling T, Spencer NG, Watremez W, Fasolino V, et al. (August 2016). "Fenamate NSAIDs inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and protect against Alzheimer's disease in rodent models". Nature Communications. 7: 12504. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712504D. doi:10.1038/ncomms12504. PMC 4987536. PMID 27509875.

- ^ Miguel-Álvarez M, Santos-Lozano A, Sanchis-Gomar F, Fiuza-Luces C, Pareja-Galeano H, Garatachea N, et al. (February 2015). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment effect". Drugs & Aging. 32 (2): 139–147. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0239-z. PMID 25644018. S2CID 35357112.

- ^ Jaturapatporn D, Isaac MG, McCleery J, Tabet N (February 2012). "Aspirin, steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006378. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006378.pub2. PMC 11337172. PMID 22336816.

- ^ Wang J, Tan L, Wang HF, Tan CC, Meng XF, Wang C, et al. (2015). "Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Alzheimer's disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 44 (2): 385–396. doi:10.3233/JAD-141506. PMID 25227314.

- ^ Melnikov V, Tiburcio-Jimenez D, Mendoza-Hernandez MA, Delgado-Enciso J, De-Leon-Zaragoza L, Guzman-Esquivel J, et al. (2021). "Improve cognitive impairment using mefenamic acid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy: additional beneficial effect found in a controlled clinical trial for prostate cancer therapy". American Journal of Translational Research. 13 (5): 4535–4543. PMC 8205720. PMID 34150033.

Further reading

edit- "Mefenamic Acid". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 28 September 2005.

- Page J, Henry D (March 2000). "Consumption of NSAIDs and the development of congestive heart failure in elderly patients: an underrecognized public health problem". Archives of Internal Medicine. 160 (6): 777–84. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.6.777. PMID 10737277.