The masculine beauty ideal is a set of cultural beauty standards for men which change based on the historical era and the geographic region.[1] These standards are ingrained in men from a young age to increase their perceived physical attractiveness.[2]

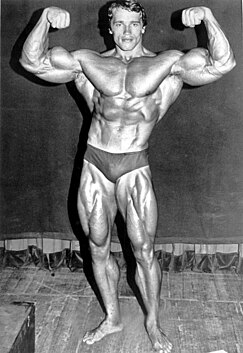

Masculine beauty ideals are mainly rooted in heteronormative beliefs about hypermasculinity, but they heavily influence men of all sexual orientations and gender identities.[3] The masculine beauty ideal traits include but are not limited to: male body shape, height, skin tones, body weight, muscle mass, and genital size.[4] Men oftentimes feel social pressure to conform to these standards in order to feel desirable, and thus elect to alter their bodies through processes such as extreme dieting, genital enlargement, radical fitness regimens, skin whitening, tanning, and other bodily surgical modifications.[5][6][7]

Colonialism

editBecause masculine beauty standards are subjective, they change significantly based on location. A professor of anthropology at the University of Edinburgh, Alexander Edmonds, states that in Western Europe and other colonial societies (Australia, and North and South America), the legacies of slavery and colonialism have resulted in images of beautiful men being "very white."[8]

Androgyny

editStandards of beauty vary based on culture and location. While Western beauty standards emphasize muscled physiques, this is not the case everywhere.[9] In South Korea and other parts of East Asia, the rise of androgynous K-pop bands have led to slim boyish bodies, vibrant hair, and make-up being more sought-after ideals of masculine beauty.[8]

Youthfulness

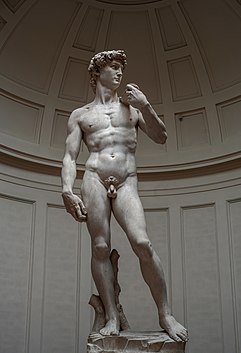

editBeauty standards have evolved over time, changing based on various factors. Youth was seen as beautiful in places such as ancient Egypt, with art as an example of this.[1] Egyptian art pieces showed youthful figures in an idealized form. Greek and Roman sculptures continued this theme of idealism but chose to represent beauty through qualities such as muscles and intellect.[1]

Weight

editOver time, wealthy and powerful figures moved away from the idealistic nature and grew to see wealth through access to scarcities as more ideal. One of these scarcities was the amount of food accessible at the time. When food shortages were a problem, excessive adipose tissue was a symbol of wealth.[10] Paintings that represented the beauty of the early modern period were of prominent and powerful figures, many showing their wealth through their excess adipose tissue.[11] Due to this, they were not painted in an idealistic way, focusing especially on the clothes and other material possessions to accentuate this wealth.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Simonova, Michaela (9 November 2021). "The Ideal Man: Male Beauty Standards Through History". The Collector. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Lee Yang, Eugene; Koeppel, Kari; Vazquez, Eli (19 March 2015). "Men's Standards Of Beauty Around The World". Buzzfeed. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Joy, Phillip; Numer, Matthew (6 January 2019). "How body ideals shape the health of gay men". The Conversation. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Hames, R. "Beauty" (PDF). University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Body image - men - Better Health Channel". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ "The Truth About Male Body Image Issues". Newport Institute. 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ McCreary, Donald R.; Saucier, Deborah M. (2009-01-01). "Drive for muscularity, body comparison, and social physique anxiety in men and women". Body Image. 6 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.09.002. ISSN 1740-1445. PMID 18996066.

- ^ a b Ali, Myra. "What does the 'perfect man' look like now?". BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Durkee, Patrick; Polo, Pablo; Pita, Miguel (April–June 2019). "Men's Bodily Attractiveness: Muscles as Fitness Indicators". Evolutionary Psychology. 17 (2). doi:10.1177/1474704919852918. PMC 10480816. PMID 31167552. S2CID 174815605.

- ^ Ferris, W.F.; Crowther, N.J. (June 2011). "Once Fat Was Fat and That Was That : Our Changing Perspectives on Adipose Tissue". CardioVascular Journal of Africa. 22 (2): 147–154. doi:10.5830/cvja-2010-083. PMC 3721932. PMID 21713306.

- ^ Hollander, Anne (23 October 1977). "When Fat was Fashion". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

External links

edit- Media related to Male beauty at Wikimedia Commons