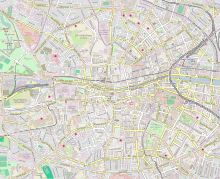

Mary Street (Irish: Sráid Mhuire)[1] is a predominantly retail street in Dublin, Ireland on the northside of the city contiguous with Henry Street.

The headquarters of Primark on the corner of Mary Street and Jervis Street | |

| Native name | Sráid Mhuire (Irish) |

|---|---|

| Namesake | St Mary's Church |

| Length | 300 m (980 ft) |

| Width | 14 metres (46 ft) |

| Location | Dublin, Ireland |

| Postal code | D01 |

| Coordinates | 53°20′56″N 6°16′00″W / 53.348794°N 6.266571°W |

| west end | Capel Street |

| east end | Henry Street, Liffey Street Upper |

It is not to be confused with the nearby Little Mary Street which runs parallel on the West side of Capel Street.

Location

editMary Street runs from Capel Street in the east to the junction of Henry Street and Liffey Street Upper in the east. [2] Previously it was also crossed by Little Denmark Street until this street was entirely erased with the construction of the Ilac Centre around 1980.

It is crossed by Upper Jervis Lane, Wolfe Tone Street, and Jervis Street.

History

editThe name is derived from the area being part of the historical lands which made up St. Mary's Abbey from 1139. The Abbey was dissolved in the 1530s and later the street became part of the parish of St Mary from 1697. It is likely that Mary Street was laid out by Jervis in the mid 1690s.[3][4]

The street is part of a larger general area developed by Humphrey Jervis after 1674 and is located in what was then one of the richest parishes in the city.[5]

Notable buildings and businesses

editVarious important institutions and buildings have been located on the street or on the location of what was later to become the street.

Langford House, 21-22 Mary Street

editLangford House was one of the earliest and the grandest structures in the area which later made up the street and was later named for Hercules Langford Rowley when it was acquired in 1743. It was described as a four-storey over basement, five-bay townhouse and was said to be originally almost Jacobean in style.[2][6][7] In 1697, Paul Barry, Keeper of the Pipe rolls and the son of Matthew Barry of Great Ship Street, took a lease of the site with a frontage of 170 feet and depth of 210 feet and erected the house in the years following before being sold on again in 1712. It is likely that the construction of Langford House and St Mary's Church were being undertaken at the same time.

In 1765, Robert Adam redesigned the interior of the house giving it more of a Georgian appearance with extensive ceiling and wall stucco work across the main entertaining rooms.[8][9] The much altered Georgian style house which was set back from the rest of main building line of the street.

For a period, the house and grounds, like many other large buildings in the city, were used as a temporary barracks until 1809.

The building was later occupied by the paving board from 1809-54 which refaced the building in brick and it was referred to as the Paving House. The Paving Board was abolished in 1854 with the functions transferring to Dublin Corporation and the building was later occupied by Bewley and Draper.[10][11]

The house was finally demolished in 1931, and replaced with nurses school for Jervis Street hospital and later with commercial and retail buildings which now form part of the facade of the Jervis Shopping Centre.[2][12][13]

Todd Burns department store

editThe former Todd Burns department store is one of the most prominent buildings on the street. It was designed by W. Mitchell and was built in 1905. It is now the location of the flagship store and head office of the retail chain Penney's (Primark) having been acquired out of bankruptcy by Galen Weston in 1969.[3][14]

In 1791, Apothecaries' Hall was erected at 40 Mary Street, at a cost of £6,000. The hall was described as a plain building and contained a spacious chemical laboratory where medicines were prepared. Lectures were delivered at the hall, and part of it was also a wholesale warehouse, where the apothecaries could procure their materials. The rear of the building backed onto Chapel Lane.[15]

Number 45 Mary Street was the location of the first cinema in Dublin, the Volta Electric Cinema, which opened in 1909 and was managed by James Joyce.[3][16]

St Mary's Church is a former Church of Ireland building which now operates as a pub and restaurant. The churchyard and adjacent graveyard now form what is called Wolfe Tone Square.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Sráid Mhuire". logainm.ie.

- ^ a b c Bennett 2005, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Clerkin, Paul (2001). Dublin street names. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-7171-3204-8. OCLC 48467800.

- ^ M'Cready, C. T. (1987). Dublin street names dated and explained. Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Carraig. p. 110. ISBN 1-85068-005-1. OCLC 263974843.

- ^ Usher, Robin. (2012). Protestant Dublin, 1660-1760: Architecture and Iconography. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-230-36216-1.

- ^ Guinness, Desmond (1912). "Records of Eighteenth-century Domestic Architecture and Decoration in Dublin". Society at the Dublin University Press. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Today FM, 125 Upper Abbey Street, Dublin 1, DUBLIN". Buildings of Ireland. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "1765 – Interior Designs, Langford House, Mary St., Dublin". Archiseek - Irish Architecture. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Drawings". collections.soane.org. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "The Registered Papers of the Chief Secretary's Office: National Archives: 1831 (Browse records)". csorp.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Wright, George Newenham (1825). "An Historical Guide to the City of Dublin: Illustrated by Engravings, and a Plan of the City". Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "CO. DUBLIN, DUBLIN, MARY STREET, LANGFORD HOUSE Dictionary of Irish Architects -". www.dia.ie. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "1931 – Former Jervis Hospital Nurses School, Mary Street, Dublin". Archiseek - Irish Architecture. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Penneys, Mary Street, Jervis Street, Dublin 1, DUBLIN". Buildings of Ireland. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Wright, George Newenham (1825). "An Historical Guide to the City of Dublin, Illustrated by Engravings, and a Plan of the City". Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Bloom or bust: what James Joyce can teach us about economics". Financial Times. 10 June 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Bennett, Douglas (2005). The Encyclopaedia of Dublin. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-717-13684-1.