The Mary River turtle (Elusor macrurus) is an endangered species of short-necked turtle in the family Chelidae. The species is endemic to the Mary River in south-east Queensland, Australia. Although this turtle was known to inhabit the Mary River for nearly 30 years, it was not until 1994 that it was recognised as a new species.[3] There has been a dramatic decrease in its population due to low reproduction rates and an increase of depredation on nests.

| Mary River turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Queensland, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Pleurodira |

| Family: | Chelidae |

| Subfamily: | Chelodininae |

| Genus: | Elusor Cann & Legler, 1994 |

| Species: | E. macrurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Elusor macrurus Cann & Legler, 1994[2]

| |

| |

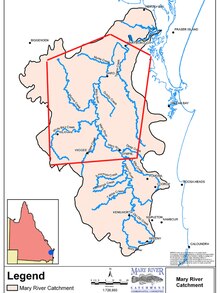

| Range is the red pentagon (from Gympie to Maryborough) | |

Taxonomy and common names

editThe Mary River turtle was first formally described in 1994. The Mary River turtle is also commonly called the green-haired turtle and the punk turtle, due to the algae that grows on its head or shell. Elusor is a monotypic genus representing a very old lineage of turtles that has all but disappeared from the evolutionary history of Australia.[4]

Description

editUnusually for turtles, males are larger than females in this species. Male Mary River turtles are one of Australia's largest turtles.[4] Specimens in excess of 50 cm (20 in) straight carapace length have been recorded. Hatchlings have a straight carapace length of 2.0–3.5 cm (0.79–1.38 in). Adult Mary River turtles have an elongated, streamlined carapace that can be plain in colour or intricately patterned. Overall colour can vary from rusty red to brown and almost black. The plastron varies from cream to pale pink. The skin colouration is similar to that of the shell and often has salmon pink present on the tail and limbs. The iris can be pale blue. The Mary River turtle uses bimodal respiration, and so is capable of absorbing oxygen via the cloaca whilst underwater. Because of this, it can stay under the water for three days at a time. However, it does regularly come to the surface to breathe air in the usual way.[4]

A unique feature of the Mary River turtle is the very large tail of males, which can measure almost two-thirds of the carapace length. Also unusual is that the tail is laterally compressed like a paddle. The tail also has haemal arches, a feature lost in all other Australian chelids. While haemal arches are documented in many cryptodiran species (including big-headed, common snapping, alligator snapping, and Pacific pond turtles), the only other pleurodiran with haemal arches is the mata mata of South America. It is probably a derived feature, but its function is not understood.[4]

Another unique feature is the exceptionally long barbels under the mandible. Proportionately, the Mary River turtle has the smallest head and largest hind feet of all the species within the catchment, which contributes to its distinction of being the fastest swimmer.[4]

The Mary River turtle is occasionally informally referred to as the green-haired turtle due to the fact that many specimens are covered with growing strands of algae which resemble hair.[5] It is also sometimes referred to as the bum-breathing turtle due to its use of its cloaca for respiration.

Threats

editThe Mary River turtle experiences many threats. Predation of hatchlings occurs by red foxes, wild dogs, and fish, especially when the turtle is at the hatchling and juvenile stages of its life. Its number one threat is the looting of its nests by dogs, foxes, and goannas. The land around the Mary River has been cleared many times, leading to low quality water and a build up of silt. Invasive plants along the river bank have also contributed to the lack of breeding success because the plants make it difficult for the Mary River turtle to go ashore and lay its eggs.[1] The Mary River turtle has the ability to blend into muddy waters and wait for unsuspecting prey to pass. Its algae-covered shell also allows it to stay hidden from predators.

Ecology and behaviour

editLittle is known about the ecology and behaviour of the Mary River turtle. It inhabits flowing and well-oxygenated sections of the Mary River basin from Gympie to Maryborough, using terrestrial nest sites.[1] Its habitat consists of riffles and shallow parts that alternate with deeper pools.[3] It prefers to inhabit clear and slow moving water. The Mary River turtle takes an unusually long time to mature; it has been estimated that females take 25 years, and males, 30 years to become adults.[6] Mature males may be aggressive towards other males or turtles of other species. The species is omnivorous, taking plant matter such as algae as well as bivalves and other small animal prey, such as fish, frogs, and sometimes even ducklings.[4]

Conservation

editIn the 1960s and 1970s, the Mary River turtle was popular as a pet in Australia, with about 15,000 sent to shops every year during a 10-year period. They were originally known as the "penny turtle"[6] or "pet shop turtle".

This species is currently listed as endangered under Queensland's Nature Conservation Act 1992, and under the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.[6] The international conservation body IUCN lists it as endangered on the IUCN Red List.[1] It is also listed on the Zoological Society of London's Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered list, part of the EDGE of Existence programme.[7][8] The Mary River Turtle has also secured 30th place on the ZSL's Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered list for reptiles. It is Australia's most endangered freshwater turtle species. The Mary River turtle was the second-most endangered freshwater turtle after the western swamp turtle (Pseudemydura umbrina) of Western Australia. The Mary River turtle was listed amongst the world's top 25 most endangered turtle species by the Turtle Conservation Fund in 2003.[9]

Australia's first reptile-focused, nonprofit conservation organization, the Australian Freshwater Turtle Conservation and Research Association, were the first to breed this species in captivity for release into the wild in 2007.[10] A purpose-built hatchery was built along the banks of the Mary River in 2019/2020. This hatchery was built to install nests and it is planned to be used in the future in order to grow the Mary River Turtle population.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Elusor macrurus ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T7664A12841291. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ Uwe, Fritz; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 330. ISSN 1864-5755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Mary River Turtle". EDGE of Existence. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Cann, J.; Legler, J.M. (1994). "The Mary River Tortoise: A New Genus and Species of Short-necked Chelid from Queensland, Australia (Testudines: Pleurodira)". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 1 (2): 81–96.

- ^ "'Genital breathing' turtle faces extinction, scientists warn". Independent.co.uk. 11 April 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Elusor macrurus in Species Profile and Threats Database". Department of the Environment. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ "Species: EDGE of Existence". Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Mary River Turtle: Elusor macrurus ". Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Turtle Conservation Fund - top 25 turtles in trouble". Turtle Conservation Fund. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Australian first". Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

External links

edit- Schmidt, Daniel J.; Espinoza, Thomas; Connell, Marilyn; Hughes, Jane M. (2018). "Conservation genetics of the Mary River turtle (Elusor macrurus) in natural and captive populations". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 28 (1): 115–123. Bibcode:2018ACMFE..28..115S. doi:10.1002/aqc.2851. ISSN 1099-0755.

- Flakus, Samantha Pauline (2003). Ecology of the Mary River Turtle, Elusor macrurus. Master of Science Thesis, University of Queensland.

- "Mary River Turtle". The Australian Museum. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "Mary River Turtle - Australia Zoo". Retrieved 17 November 2021.