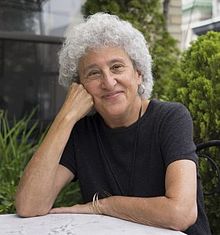

Marion Nestle (born 1936) is an American molecular biologist, nutritionist, and public health advocate. She is the Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health Emerita at New York University.[2][3] Her research examines scientific and socioeconomic influences on food choice, obesity, and food safety, emphasizing the role of food marketing.[4][5]

Marion Nestle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 10, 1936 New York[1] |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Known for | Public health advocacy, opposition to unhealthy foods, promotion of food studies as an academic field |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | New York University |

| Thesis | Purification and properties of a nuclease from Serratia marcescens (1968) |

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Audio | |

| Video | |

Through her work at NYU and her award-winning books, Nestle has had a national influence on food policy, nutrition, and food education.[6] Nestle became a Fellow of the American Society for Nutritional Sciences in 2005.[7] In 2019 she received the Food Policy Changemaker Award, as a "leader who is working to transform the food system".[8]

In 2022, the University of California Press published Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics, a memoir.[9]

Education

editNestle was born to a working class Jewish family.[10] Nestle's name is unrelated to the company Nestlé, and is pronounced Nes-sul.[11]

She received her BA in bacteriology from UC Berkeley, Phi Beta Kappa (1959). Her degrees include a Ph.D. in molecular biology (1968) and an M.P.H. in public health nutrition (1986), both from the University of California, Berkeley.[3][12]

Nestle has listed Wendell Berry, Frances Moore Lappé, Joan Gussow, and Michael Jacobson as people who inspired her.[13]

Career

editNestle undertook postdoctoral research in biochemistry and developmental biology at Brandeis University, joining the faculty in biology in 1975.[6] Being assigned to teach a nutrition course stimulated her interest in food and nutrition and using them to teach critical thinking in biology. She describes the experience as like “falling in love".[14][6]

From 1976 to 1986, Nestle was associate dean for human biology at the School of Medicine of the University of California, San Francisco.[15] She lectured in biochemistry, biophysics, and medicine[12] and developed a teaching program for medical students in nutrition.[7]

In 1986 Nestle became staff director for nutrition policy in the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). From 1986 to 1988, she was senior nutrition policy advisor at HHS. She was editor of the Surgeon General's Report on Nutrition and Health (1988)[15] and contributed to a report from the Food and Nutrition Board: Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk (1989). These reports set out the scientific background for the 1990 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.[7]

In 1988, Nestle was appointed of Home Economics and Nutrition (now Nutrition and Food Studies) in the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development Studies at New York University, holding the position of Chair from 1988-2003. She accepted the Paulette Goddard Professorship in 2004, and became Professor Emerita in 2017.[16][17] She has also been a Visiting Professor of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University.[12] In 1996 Nestle founded the food studies program at New York University with food consultant Clark Wolf. Nestle hoped to raise public awareness of food and its role in culture, society, and personal nutrition. In this, she not only succeeded but also inspired other universities to launch their own programs.[6]

Nestle is the author of numerous articles in professional publications and has won awards for a number of her books. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health was first published in 2002, winning a James Beard Literary Award, an Association of American Publishers Award for Public Health, and a Harry Chapin Media Award for Best Book.[18][19][20] Safe Food (2003) won the Daniel E. Griffiths Research Award from the Steinhardt School of Education in 2004.[21] In 2007 What to Eat won the James Beard Foundation Award for best food reference book[22] and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society's Better Life Award.[23] In 2012, Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics (co-authored with Dr. Malden Nesheim) won a book of the year award from the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).[24] Eat, Drink Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Food Politics won an IACP award in 2014.[25] Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning) won the 2016 James Beard Foundation Award for Writing and Literature[26] and the Jane Grigson Award for distinguished scholarship from the International Association of Culinary Professionals.[27]

Nestle wrote the "Food Matters" column for the San Francisco Chronicle from 2008 to 2013. She blogs at foodpolitics.com, and tweets from @marionnestle.[28] She has appeared in the documentary films Super Size Me (2004), Food, Inc. (2008), Food Fight: The Inside Story of the Food Industry (2008), Killer at Large (2008), In Organic We Trust (2012), A Place at the Table (2012),[29] Fed Up (2014),[30] In Defense of Food (2015),[31] and Super Size Me 2: Holy Chicken! (2017).[32]

Nestle received the American Public Health Association's Food and Nutrition Section Award for Excellence in Dietary Guidance in 1994 and was named Nutrition Educator of the Year by Eating Well magazine in 1997.[3]

Nestle received the John Dewey Award for Distinguished Public Service from Bard College in 2010[33] and in 2011 was named a Public Health Hero by the University of California School of Public Health at Berkeley.[34] In 2011, Forbes magazine listed Nestle as number 2 of "The world's 7 most powerful foodies."[35][36] She received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Transylvania University in Kentucky in 2012.[37] In 2013, she received the James Beard Leadership Award[38] and Healthful Food Council's Innovator of the Year Award and the Public Health Association of New York City's Media Award in 2014.[17] In 2016, Nestle was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Macaulay Honors College, City University of New York.[39]

In 2018 Nestle was honored with a Trailblazer Award from the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).[40] She also received the Grand Dame Award of Les Dames d’Escoffier International[2] and was appointed to Heritage Food Radio’s Hall of Fame.[41] In 2019 she became the inaugural recipient of the Food Policy Changemaker Award, given by the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center.[8]

Nestle visited the Edinburgh Science Festival in 2023 to receive the Edinburgh Medal, which is awarded each year to those who make a significant contribution to the understanding and well-being of humanity through science and technology.[42]

Works

editNestle has published at least 15 books and numerous articles.[17] Her books include:

- Nutrition in Clinical Practice. Greenbrae, California: Jones Medical Publications. 1985. ISBN 978-0-930010-11-9.

- Nestle, Marion, ed. (1988). The Surgeon General's Report on Nutrition and Health. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.[43][44]

- Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-520-24067-4. Reissued 2007, 2013.

- Safe Food: Bacteria, Biotechnology, and Bioterrorism. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-520-23292-1.[45][46] Republished as Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety (Updated and expanded ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-520-26606-3.

- Nestle, Marion; Dixon, L. Beth, eds. (2004). Taking sides. Clashing views on controversial issues in food and nutrition (1st ed.). Guilford, Conn.: McGraw-Hill/Dushkin. ISBN 9780072922110.

- What to Eat. New York: North Point Press (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). 2006. ISBN 978-0-86547-738-4.

- Pet Food Politics: The Chihuahua in the Coal Mine. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-520-25781-8.

- Nestle, Marion; Nesheim, Malden (2010). Feed Your Pet Right (1st Free Press trade pbk. ed.). New York: Free Press/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-6642-0.

- Nestle, Marion; Nesheim, Malden (2012). Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-262881.[47]

- Eat, Drink, Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Food Politics. Rodale Books. 2013. ISBN 978-1609615864.

- Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (And Winning). Oxford University Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0190263430.

- Williams, Simon; Nestle, Marion, eds. (2016). Big Food : critical perspectives on the global growth of the food and beverage industry. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138945944.

- Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat. Basic Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1541617315.[48]

- Let's ask Marion: What You Need to Know about the Politics of Food, Nutrition and Health. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2020. ISBN 978-0-520-97469-2. (Marion Nestle, in conversation with Kerry Trueman.)

- Slow cooked : an unexpected life in food politics. Oakland, California: University of California Press. 2022. ISBN 9780520384156. (Memoir.)[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Dangalan, Claire (2015-07-12). "Marion Nestle: Food Scientist Extraordinaire". Ananke. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ a b "Marion Nestle Earns LDEI Grand Dame Award". Les Dames d'Escoffier Chicago. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Nestle, Marion 1936-". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Interview: Marion Nestle". PBS Frontline. December 10, 2003.

- ^ Reiss, Sami (13 October 2022). "How Marion Nestle Changed the Way We Talk About Food". GQ. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Turow, Eve (20 June 2013). "Marion Nestle on Her History With Food Studies and the Future of Food Politics". Village Voice. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ^ a b c "PROCEEDINGS OF THE SIXTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR NUTRITIONAL SCIENCES San Diego, CA April 1–5, 2005". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (9): 2274–2289. 1 September 2005. doi:10.1093/jn/135.9.2274. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b Appel, Deirdre (14 June 2019). "Food Policy Changemaker Award: Dr. Marion Nestle - Hunter College". NYC Food Policy Center (Hunter College). Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Professor of Food Studies Marion Nestle Publishes Memoir | NYU Steinhardt". steinhardt.nyu.edu. October 27, 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ ""Slow Cooked": How Marion Nestle Revitalized Food Studies". Forbes. 27 September 2022. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ James (2018).

- ^ a b c "Marion Nestle - Nobel Conference 46 | Nobel Conference - 2010". Gustavus Adolphus College. October 6, 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Marshall, Kate (2013). "Ten Years of Food Politics: An Interview with Marion Nestle". Gastronomica. 13 (3): 1–3. doi:10.1525/gfc.2013.13.3.1.

- ^ "Interview with Marion Nestle". American Society for Nutrition. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH". WebMD. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Marion Nestle | Big Think". Big Think. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ^ a b c "Marion Nestle". NYU Steinhardt. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "NYU's Nestle, Author of Award-Winning "Food Politics," Available for Comment On Nutrition and Food Industry". NYU. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Namie, Joylin (19 September 2011). "Review: Food Politics". FoodAnthropology. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Book awards: Harry Chapin Media Award | LibraryThing". LibraryThing. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Marion Nestle Papers, 1970-2017 MSS.159". Fales Library & Special Collections. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Awards Search". James Beard Foundation. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Gardner, Jan (March 2, 2007). "Prize season". Boston.com. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Marion Nestle: Discusses the Goal of Large Corporate Food Companies". Dr. McDougall Health & Medical Center. June 17, 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Forbes, Paula (15 March 2014). "IACP Announces 2014 Food Writing Award Winners". Eater. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "WINNERS ANNOUNCED FOR THE 2016 JAMES BEARD FOUNDATION BOOK, BROADCAST & JOURNALISM AWARDS NEW YORK, NY" (PDF). James Beard Foundation. April 26, 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Soda Politics: Taking On Big Soda (And Winning)". Real Food Media.

- ^ "About Marion Nestle". foodpolitics.com. 2008-11-26. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ IMDB entry

- ^ Rosenberg, Martha (May 22, 2014). "Why Is the U.S. So Fat? Katie Couric Documentary Fed Up Seeks to Explain". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ "In Defense of Food: Transcript". PBS.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Spurlock, Morgan (director) (September 6, 2019). Super Size Me 2: Holy Chicken! (Film Documentary). Archived from the original on 2021-12-19. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ "Bard College Catalogue at Bard College". Bard College. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Devitt, James. "Nestle Recognized as Public Health Hero for Leadership in Nutrition Policy and Combating Obesity". New York University. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Pollan, Michael (November 2, 2011). "The World's 7 Most Powerful Foodies". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Brion, Raphael (7 November 2011). "Michael Pollan Lists the World's 'Most Powerful Foodies'". Eater. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Expert nutritionist Marion Nestle receives honorary degree from Transylvania University - Transylvania University - 1780". 1780 | the Official Blog of Transylvania University. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Hoffman, Anya (October 23, 2013). "2013 JBF Leadership Award Winner Marion Nestle | James Beard Foundation". James Beard Foundation. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Food Studies Scholar and Consumer Advocate Marion Nestle Is Macaulay Commencement Speaker". CUNY Newswire. April 18, 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Spiegel, Alison (February 25, 2018). "The 2018 IACP Award-Winners". Food & Wine. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Marion Nestle | Heritage Radio Network". Heritage Radio Network. February 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Edinburgh Medal - Edinburgh Science". Edinburgh Science. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ Nestle, Marion (1 September 1988). "The surgeon general's report on nutrition and health: New federal dietary guidance policy". Journal of Nutrition Education. 20 (5): 252–254. doi:10.1016/S0022-3182(88)80067-0. ISSN 0022-3182.

- ^ McGinnis, J M; Nestle, M (1 January 1989). "The Surgeon General's Report on Nutrition and Health: policy implications and implementation strategies" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 49 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1093/ajcn/49.1.23. PMID 2912006.

- ^ O’Doherty Jensen, Katherine (15 March 2004). "Safe Food: Bacteria, biotechnology, and bioterrorism". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 113 (6): 787. doi:10.1172/JCI21319. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 362128.

- ^ Schoch-Spana, Monica (2006). "Review of Safe Food: Bacteria, Biotechnology, and Bioterrorism". Agricultural History. 80 (4): 470–472. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 4617780. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "WHY CALORIES COUNT | Kirkus Reviews". Kirkus Reviews. April 1, 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Abrams, Frances E. (November 1, 2018). "Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat". new york journal of books. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

Sources

edit- James, Cyan (October 5, 2018). "Junk food, junk science?". Science. 362 (6410): 38. Bibcode:2018Sci...362...38J. doi:10.1126/science.aau6602.

External links

edit- Foodpolitics.com

- Marion Nestle at IMDb

- "Video: A Deep Dive into the "Raw Water" Craze - The Daily Show with Trevor Noah (Video Clip)". Comedy Central. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018.

- Marion Nestle Papers at Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Special Collections.