Mariner-H (Mariner Mars '71), also commonly known as Mariner 8, was (along with Mariner 9) part of the Mariner Mars '71 project. It was intended to go into Mars orbit and return images and data, but a launch vehicle failure prevented Mariner 8 from achieving Earth orbit and the spacecraft reentered into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after launch.[1]

Mariner 8 is identical in design with Mariner 9 | |

| Mission type | Mars orbiter |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA/JPL |

| Mission duration | Failed to orbit |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 997.9 kilograms (2,200 lb) |

| Dry mass | 558.8 kilograms (1,232 lb) |

| Power | 500 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | May 9, 1971, 01:11:02 UTC |

| Rocket | Atlas SLV-3C Centaur-D |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36A |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Areocentric |

| Epoch | Planned |

Mission

editMariner 8 was launched on an Atlas-Centaur SLV-3C booster (AC-24). The main Centaur engine was ignited 265 seconds after launch, but the upper stage began to oscillate in pitch and tumbled out of control. The Centaur stage shut down 365 seconds after launch due to starvation caused by the tumbling. The Centaur and spacecraft payload separated and re-entered the Earth's atmosphere approximately 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) downrange and fell into the Atlantic Ocean about 560 kilometres (350 mi) north of Puerto Rico.

A guidance system failure was suspected as the culprit, but JPL navigation chief Bill O'Neil dismissed the idea that the entire guidance system had failed. He argued that an autopilot malfunction had occurred since the event had occurred at the exact moment when the system was supposed to activate. Investigation proceeded quickly and the problem was soon discovered to be the result of a malfunction in the pitch rate gyro amplifier. A diode intended to protect the system from transient voltages was thought to have been damaged during repairs/installation of the pitch amplifier's printed circuit board, something that would not have been detected through bench tests.

As of 2024[update], Mariner 8 is the most recent US planetary probe to be lost in a launch vehicle malfunction.

Mariner Mars 71 Project

editThe Mariner Mars 71 project consisted of two spacecraft (Mariners H and I), each of which would be inserted into a Martian orbit, and each of which would perform a separate but complementary mission. Either spacecraft could perform either of the two missions. The two spacecraft would have orbited the planet Mars a minimum of 90 days, during which time data would be gathered on the composition, density, pressure, and temperature of the atmosphere, and the composition, temperature, and topography of the surface. Approximately 70 percent of the planetary surface was to be covered, and temporal as well as spatial variations would be observed. Some of the objectives of the Mariner-H mission were successfully added to the Mariner-I (Mariner 9) mission profile.[1]

Total research, development, launch, and support costs for the Mariner series of spacecraft (Mariners 1 through 10) was approximately $554 million.[1]

Spacecraft and subsystems

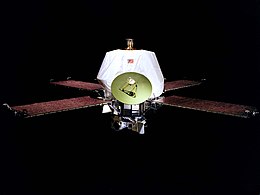

editThe Mariner 8 spacecraft was built on an octagonal magnesium frame, 45.7 centimetres (18.0 in) deep and 138.4 centimetres (54.5 in) across a diagonal. Four solar panels, each 215 by 90 centimetres (85 in × 35 in), extended out from the top of the frame. Each set of two solar panels spanned 6.89 metres (22.6 ft) from tip to tip. Also mounted on the top of the frame were two propulsion tanks, the maneuver engine, a 1.44 metres (4 ft 9 in) long low gain antenna mast and a parabolic high gain antenna. A scan platform was mounted on the bottom of the frame, on which were attached the mutually bore-sighted science instruments (wide- and narrow-angle TV cameras, infrared radiometer, ultraviolet spectrometer, and infrared interferometer spectrometer). The overall height of the spacecraft was 2.28 metres (7 ft 6 in). The launch mass was 997.9 kilograms (2,200 lb), of which 439.1 kilograms (968 lb) were expendables. The science instrumentation had a total mass of 63.1 kilograms (139 lb). The electronics for communications and command and control were housed within the frame.

Spacecraft power was provided by a total of 14,742 solar cells which made up the 4 solar panels with a total area of 7.7 square metres (83 sq ft) area. The solar panels could produce 800 W at Earth and 500 W at Mars. Power was stored in a 20 ampere hour nickel-cadmium battery. Propulsion was provided by a gimbaled engine capable of 1340 N thrust and up to 5 restarts. The propellant was monomethyl hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. Two sets of 6 attitude control nitrogen jets were mounted on the ends of the solar panels. Attitude knowledge was provided by a Sun sensor, a Canopus star tracker, gyroscopes, an inertial reference unit, and an accelerometer. Passive thermal control was achieved through the use of louvres on the eight sides of the frame and thermal blankets.

Spacecraft control was through the central computer and sequencer which had an onboard memory of 512 words. The command system was programmed with 86 direct commands, 4 quantitative commands, and 5 control commands. Data was stored on a digital reel-to-reel tape recorder. The 168 metres (551 ft) 8-track tape could store 180 million bits recorded at 132 kbit/s. Playback could be done at 16, 8, 4, 2, and 1 kbit/s using two tracks at a time. Telecommunications were via dual S-band 10 W/20 W transmitters and a single receiver through the high gain parabolic antenna, the medium gain horn antenna, or the low gain omnidirectional antenna.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Rod Pyle (2012). Destination Mars: New Explorations of the Red Planet. Prometheus Books. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-1-61614-589-7.