Malvern Water is a brand of bottled drinking water obtained from a spring in the range of Malvern Hills that marks the border between the counties of Herefordshire and Worcestershire in England.[1] The water is a natural spring water from the hills that consist of very hard granite rock. Fissures in the rock retain rain water, which slowly permeates through, escaping at the springs.[2] The springs release an average of about 60 litres a minute.[3] The flow rate depends on rainfall and can vary from as little as 36 litres (8 gallons) per minute to over 350 litres (77 gallons) per minute.[4][5]

| |

| Country | England |

|---|---|

| Source | Malvern Hills |

| Type | Natural spring water |

| All concentrations in milligrams per liter (mg/L); pH without units | |

Schweppes began bottling the water on a commercial scale in 1850 and it was first offered for sale at the Great Exhibition of 1851.[6] Since the owners, Coca-Cola Enterprises, closed their Colwall plant in November 2010, Malvern Water is now exclusively bottled on a smaller scale by the family-owned Holywell Water Company Ltd under the name Holywell Malvern Spring Water who offer the water in still and sparkling (carbonated) versions.

History

editMalvern Water has been bottled and distributed in the United Kingdom and abroad from the 16th century,[2] with water bottling at the Holy Well being recorded in 1622.[6] Various local grocers bottled and distributed Malvern water during the 19th and early 20th centuries, but it was first bottled on a large commercial scale by Schweppes, who opened a bottling plant at Holywell in Malvern Wells in 1850. The water was first introduced by Schweppes as Malvern Soda, later renaming it Malvern Seltzer Water in 1856.[7][8] In 1890 Schweppes moved away from Holywell, entered into a contract with a Colwall family, and built a bottling plant in the village in 1892.[7] The Holywell was subsequently leased to John and Henry Cuff, who bottled there until the 1960s.[9]

The Holywell became derelict until 2009 when, with the aid of a Lottery Heritage grant, production of 1200 bottles per day of Holywell Malvern Spring Water was recommenced by an independent family-owned company.[10] Malvern water continues to be sold by the Hollywell Spring Water Co. in Malvern Wells whose three employees produce around 1,200 bottles a day.[11] The well is believed to be the oldest bottling plant in the world.[12]

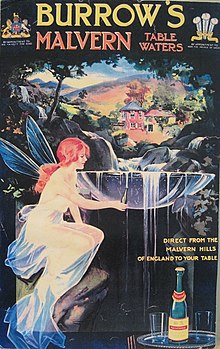

In the 1850s Malvern Water was bottled by John and William Burrow at the Bottling Works Spring in Robson Ward's yard on Belle Vue Terrace in Great Malvern. Bottling ceased here in the 1950s and the former bottling works are now a selection of shops, coffee house and kitchen showroom. Water for the Bottling Works Spring is piped from St Ann's Well.[13]

In 1927, Schweppes acquired from the Burrow family, Pewtress Spring in Colwall, on the western side of the Herefordshire Beacon, approximately two miles from Colwall village.[7][14] The source emerges at the fault line between the Silurian thrust and the Precambrian diorite and granite above it.[7] The spring was renamed Primeswell Spring, and in 1929 Schweppes commenced bottling.[14] The factory employed 25 people who bottled 26 million bottles annually.[15] It was operated by Coca-Cola Enterprises Ltd., and the water was sold under the Schweppes brand name.[16]

On 20 October 2010 Coca-Cola Enterprises, who owned the Malvern brand, announced that due to the declining market share Malvern has on the overall water market, production of their water would be ceasing on 3 November 2010. On 28 October 2011, it was reported that the Colwall bottling plant would be sold to a property developer.[17] The factory was demolished and a housing estate was built on the land. One building remains, the Grade II listed tank house, built in 1892.[18]

Malvern water continues to be sold by the Hollywell Spring Water Co. in Malvern Wells whose three employees produce around 1,200 bottles a day.[11] In 2011, Holywell was awarded Most Promising New Business in Herefordshire & Worcestershire 2011 by the Chamber of Commerce.[19]

Purity

editThe natural untreated water is generally devoid of all minerals, bacteria, and suspended matter, approaching the purity of distilled water. In 1987 Malvern gained official EU status as a natural mineral water, a mark of purity and quality. However, in spite of regular quality analysis,[20] Malvern's reputation for purity suffered a blow when the rock that filters the water dried out during 2006, allowing the water from heavy storms to flow through it too quickly for the natural filtering process to take place efficiently. Due to the slight impurities, the Coca-Cola Company, manufacturer of the Schweppes brand, had to install filtration equipment,[3] which reclassifies the water as spring water under European Union law.[21] Consequently, the labels were changed from: the original English mineral water to read the original English water[3]

In 1998, Coca-Cola Schweppes recalled stocks of carbonated Malvern Water due to traces of benzene found in the carbon dioxide delivered to the bottling plants from the Terra Nitrogen Company near Bristol, which distributes the gas to carbonated drinks manufacturers.[22]

Royalty

editMalvern Water has been drunk by several British monarchs.[23] Queen Elizabeth I drank it in public in the 16th century; in 1558 she accorded John Hornyold, a Catholic bishop and lord of the manor, the right to use the land under the condition that travellers and pilgrims continue to be able to draw water from the Holy Well spring.[6] A royal warrant was granted by Princess Mary Adelaide in 1895 and by King George V in 1911.[3] Queen Victoria refused to travel without it and Queen Elizabeth II took it with her whenever she travelled.[24]

References

edit- ^ 52°06′27″N 2°19′48″W / 52.10737°N 2.32994°W

- ^ a b Smart, Mike (2009), The Malvern Hills, London: Frances Lincoln Ltd, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-7112-2915-0

- ^ a b c d James Connell (11 April 2007), "MALVERN: Why taste of the hills is no longer called mineral water", Worcester News, retrieved 3 July 2010

- ^ Blyth, Francis George Henry (1967). "A Geology for Engineers". Edward Arnold: 273.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) snippet view second snippet view - ^ "Hydrology and Fluvial Geomorphology", Area Geology, Abberley and Malvern Hills Geopark, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 12 July 2010

- ^ a b c "Welcome to Malvern Wells Parish Council". Worcestershire County Council. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Official Malvern Water brochure. Coca-Cola Enterprises Limited. 2009.

- ^ "Schweppe's Malvern Seltzer Water", Medical Times and Gazette Advertiser, 12 – New series (301): 328, 5 April 1856, retrieved 14 July 2010

- ^ Richardson, Linsdall (1930), Wells and springs of Worcestershire, (Memoirs of the Geological Survey, England and Wales), London: HM Stationery Office, p. 119, retrieved 16 July 2010

- ^ "MALVERN HERITAGE PROJECT". Malvern Spa Association. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b Morris, Steven (21 October 2010). "Malvern Water to cease production". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Al Rasheed, Tarik (9 November 2009). "Historic bottling plant at Holy Well open for business again". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Springs and Spouts of the Northern Hills. (MHAONBWaterleafletNorthernHillsrevised,Oct10_000.pdf brochure) Retrieved 2 September 2016, Malvern Hills Conservators (UK Government), 16 June 2003

- ^ a b Schweppes & Malvern Water, Malvern-Hills.Co, archived from the original on 11 July 2012, retrieved 14 July 2010

- ^ "Coca-Cola GB and Ireland receives stewardship award for Malvern Water". Coca-Cola GB, Press Office. 1 September 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Coca-Cola Scwheppes Water web page". Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "Hopes for revival of Malvern Water dashed". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group Ltd. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Thomas, James (22 July 2021). "What could happen to last building at Malvern Water plant". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group Ltd. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Chamber Business Awards Previous Winners". Herefordshire & Worcestershire Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "PRIVATE WATER SUPPLIES (ENGLAND) REGULATIONS 2016". Worcestershire Regulatory Services. 2016. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Van Der Aa, Monique (2003). "Classification of mineral water types and comparison with drinking water standards". Environmental Geology. 44 (5): 554–563. doi:10.1007/s00254-003-0791-4. hdl:10029/11409. S2CID 97428950.

- ^ "Leading soft drinks withdrawn", BBC News, 1 June 1998, retrieved 14 July 2010

- ^ Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 37. House of Commons. 15 February 1983. col. 268–274.

- ^ Wallop, Harry (21 October 2010). "Queen's favourite Malvern Water stops production". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

Bibliography

edit- "Burrow's Patent Racks", Year-Book of Pharmacy: 699 (n711 in electronic page field), 1871, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Brough, John Cargill (1869), "W. & J. Burrow's Patented Inventions", Exeter Change for the British Lions: 30, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Thom, Adam Bissett, ed. (1877), "W. & J. Burrow's Malvern Spring Water", The Upper Ten Thousand, George Routledge & Sons: 8 retrieved 14 July 2010 Snippet 1 Snippet 2 Snippet 3

- Cowie, Leonard W.; Hembry, Evelyn E, eds. (1997), British Spas from 1815 to the Present: A Social History, Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Press, pp. 67, 100, 231, 245, ISBN 0-8386-3748-5, retrieved 14 July 2010

- "Water worker's strike sees Malvern Water sales soar 50 %", The Economist, vol. 286, p. 55, 1983, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Emmins, Colin (1991), Soft Drinks: Their Origin and History, Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications Ltd, ISBN 0-7478-0125-8

- Jensen, Benedikte Herold (2007), That's The Way, Denmark: Systime, pp. 143–147, ISBN 978-87-616-1139-0, retrieved 14 July 2010

- LaMoreaux, Philip E.; Tanner, Judy T, eds. (2001), Springs and bottled water of the world: Ancient history, source, occurrence, quality and use, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61841-4, retrieved 13 July 2010

- Mascha, Michael (2006), Fine Waters: A Connoisseur's Guide to the World's Most Distinctive Bottled Waters, p. 18, ISBN 978-1-59474-119-7, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Ray, Cyril (1981), "On The Tap", Punch, 280: 688 retrieved 14 July 2010 Snippet 1Snippet 2snippet 3 retrieved 14 July 2010 (On Schweppes take over of W & J Burrow's bottling plant)

- Senior, Dorothy; Dedge, Nick, eds. (2005), Technology of Bottled Water (2nd ed.), Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 1-4051-2038-X, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Sutton, John (1991), Sunk Costs and Market Structure: Price, Competition, Advertising, and the Evolution of Concentration, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, p. 461, ISBN 0-262-19305-1, retrieved 14 July 2010

- Thompson, Francis M.L, ed. (1996), The Cambridge Social History of Britain 1750–1950, vol. 2: People and their environment, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 267, ISBN 0-521-25789-1, retrieved 14 July 2010

External links

edit- Malvernwaters.co.uk ( no longer active as the website for this brand of water )

- Holy Well on Malvern Wells Parish Council web site.

- Malvern Hills Conservators