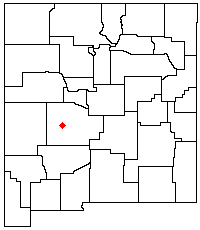

The Magdalena Mountains are a regionally high, mountain range in Socorro County, in west-central New Mexico in the southwestern United States. The highest point in the range is South Baldy, at 10,783 ft (3,287 m), which is also the tallest peak in Socorro County. The range runs roughly north–south and is about 18 miles (28 km) long. The range lies just south of the village of Magdalena, and about 18 miles (28 km) west of Socorro. The Magdalena Mountains are an east-tilted fault-block range, superimposed on Cenozoic calderas. The complex geologic history of the range has resulted in spectacular scenery, with unusual and eye-catching rock formations. They form part of the western edge of the Rio Grande Rift Valley, fronting the La Jencia Basin. The mountains remain isolated and natural due to the absence of any significant human development within or near the range.

| Magdalena Mountains | |

|---|---|

The view looking southwest at Sawmill Canyon, near the Langmuir Research Site in the Magdalena Mountains. | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | South Baldy |

| Elevation | 10,783 ft (3,287 m) |

| Coordinates | 33°59′27″N 107°11′15″W / 33.99083°N 107.18750°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 18 mi (29 km) North-South |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Mexico |

The range takes its name from a volcanic peak on the west side, named Magdalena Peak, after Mary Magdalene. A talus formation and shrub growth on the east slope of Magdalena Peak is said to resemble a woman's face.[1] According to Julyan's Place Names of New Mexico, one legend about the mountain purports that "a group of Mexicans were besieged by Apaches on the mountain, when the face of Mary Magdalene miraculously appeared, frightening the Indians away."[2]

Management

editMost of the Magdalena Mountains are within the Magdalena Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest, and parts are also administered by the Bureau of Land Management. While there are no designated Wilderness areas in the range, the Ryan Hill Inventoried Roadless Area (IRA) is sizeable (up to approximately 35,000 acre). In 1980, Public Law 96-550 established Langmuir Research Site in the Magdalena Mountains. Congress found the mountains uniquely suited for atmospheric and astronomical research which has been conducted at Langmuir Laboratory near South Baldy since the mid-1960s. The Act designated a 31,000 acre portion of the mountain as essentially roadless, but not wilderness. There is overlap between the Ryan Hill IRA and the congressionally designated Langmuir Research Site management area. Directly adjacent to the southern boundary of the Ryan Hill IRA lies the Devil's Reach Wilderness Study Area (WSA). The Devil's Reach WSA and its neighboring Devil's Backbone WSA are both managed by the BLM. The Ryan Hill IRA, Devil's Reach WSA, and Devil's Backbone WSA combine to form a 44,050-acre contiguous roadless area on the southern end of the range.[1][3]

Recreation

editA well-established network of trails exists in the Magdalena Mountains, providing abundant hiking, backpacking, hunting, horseback-riding, and stargazing opportunities. The Forest Service notes that there are over 60 miles of trails in the Magdalenas. Over half of the trails are in the Ryan Hill Inventoried Roadless Area.

The Water Canyon Campground is a developed campsite located at 6,800 ft elevation in the Magdalenas.

Significant summits include:[4]

| Mountain | Height (ft) | Height (m) | Coordinates | Prominence (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Baldy | 10,783 | 3,287 | 33°59′29″N 107°11′17″W / 33.9913°N 107.1880°W | 3,813 |

| Timber Peak | 10,510 | 3,203 | 33°58′44″N 107°09′37″W / 33.9790°N 107.1603°W | 650 |

| North Baldy | 9,858 | 3,005 | 34°03′01″N 107°10′53″W / 34.0503°N 107.1813°W | 554 |

| Buck Peak | 9,085 | 2,769 | 33°58′58″N 107°07′51″W / 33.9827°N 107.1307°W | 625 |

Scientific research

editAt the southern end of the main range crest, just south of South Baldy, lies the Langmuir Laboratory for Atmospheric Research of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology (New Mexico Tech). The Langmuir's location in the Magdalena Mountains was chosen "because thunderstorms are initiated by the mountains and the storms are often isolated, stationary, and relatively small" and occur with high frequency. Visiting scientists at Langmuir also study bats, hummingbirds, butterflies and plant life in the area.[5] The same area hosts the Magdalena Ridge Observatory Interferometer, also operated by New Mexico Tech, along with other institutions.

History

editThe history of the Magdalena Mountains is intimately linked with the rich history of the surrounding area. Basham noted in his report documenting the archeological history of the Cibola's Magdalena Ranger District that "[t]he heritage resources on the district are diverse and representative of nearly every prominent human evolutionary event known to anthropology. Evidence for human use of district lands date back 14,000 years to the Paleoindian period providing glimpses into the peopling of the New World and megafaunal extinction."[6] Much of the now Magdalena Ranger District was a province of the Apache. Bands of Apache effectively controlled the Magdalena-Datil region from the seventeenth century until they were defeated in the Apache Wars in the late nineteenth century.[6]

A mining rush followed the Apache wars – gold, silver, and copper were found in the mountains. While miners combed the mountains for mineral riches during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stockmen drove tens of thousands of sheep and cattle to stockyards at the village of Magdalena, then linked by rail with Socorro.[7] In fact, the last regularly used cattle trail in the United States stretched 125 miles westward from Magdalena. The route was formerly known as the Magdalena Livestock Driveway, but more popularly known to cowboys and cattlemen as the Beefsteak Trail. The trail began use in 1865 and its peak was in 1919. The trail was used continually until trailing gave way to trucking and the trail officially closed in 1971.[6]

Ecology

editThe Magdalena Mountains contain a wide variety of vegetation types, including scrubland, pinyon-juniper woodland, ponderosa pine forest, spruce-fir forest, grassland, and riparian areas. At lower elevations, grasses include black and sideoats grama, poverty threeawn, fluffgrass, burrograss, and galleta grass. Higher up, grass species include blue and hairy grama, little blue stem, and Arizona fescue. Shrubs that are mixed in the grasslands include sotol, cholla, yucca, Apache plume, mountain mahogany, shrub live-oak, gambel oak, and alligator juniper.

The range of habitat areas available is reflected by the variety of wildlife in the area. The mountains are home to mountain lions, black bears, pronghorns, mule deer, coyotes, red and grey foxes, bald and golden eagles, prairie falcons, kestrel, and Mearn's quail. Several thousand acres of Mexican spotted owl critical habitat lie in the range. The Magdalenas provide habitat and an east–west movement corridor for mountain lions, and the area is considered important for species movement across the landscape.[8] The Nature Conservancy identified the Magdalena Mountains as part of a key conservation area due to their ecosystem diversity and species richness.[9]

-

The Magdalena Mountains contain critical habitat for the threatened Mexican spotted owl.

-

A pronghorn herd standing in front of the Magdalena Mountains.

-

A mule deer fawn in the snow.

-

A mountain lion in the Cibola National Forest.

-

The Magdalena Mountains are home to elk.

-

A black bear in Cibola National Forest.

Gallery

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Butterfield, Mike, and Greene, Peter, Mike Butterfield's Guide to the Mountains of New Mexico, New Mexico Magazine Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-937206-88-1

- ^ Julyan, Robert (1996). The Place Names of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ Magdalena Mountains at the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance

- ^ NM peaks on Lists of John Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Langmuir Laboratory for Atmospheric Research. "1977 Lab Brochure". New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology.

- ^ a b c Basham, M. (2011). Magdalena Ranger District Background for Survey. US Forest Service.

- ^ Julyan, Robert (2006). The Mountains of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ Menke, K. (2008). Locating Potential Cougar (Puma concolor) Corridors in New Mexico Using a Least-Cost Path Corridor GIS Analysis (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15.

- ^ The Nature Conservancy (2004). Chapter 10: Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Cibola National Forest, Mountain Districts in Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3.