Macushi is an indigenous language of the Carib family spoken in Brazil, Guyana and Venezuela. It is also referred to as Makushi, Makusi, Macuxi, Macusi, Macussi, Teweya or Teueia. It is the most populous of the Cariban languages. According to Instituto Socioambiental, the Macushi population is at an estimated 43,192, with 33,603 in Brazil, 9,500 in Guyana and 89 in Venezuela.[2] In Brazil, the Macushi populations are located around northeastern Roraima, Rio Branco, Contingo, Quino, Pium and Mau rivers. Macuxi speakers in Brazil, however, are only estimated at 15,000.

| Macushi | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Brazil, Guyana, a few in Venezuela |

| Ethnicity | Macushi |

Native speakers | 18,000 (2006)[1] |

Cariban

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mbc |

| Glottolog | macu1259 |

| ELP | Makushi |

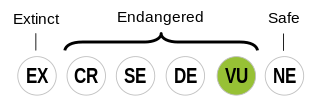

Macushi is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Crevels (2012:182) lists Macushi as “potentially endangered”,[3] while it is listed on the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger as “vulnerable”.[4] Its language status is at 6b (Threatened). The Macushi communities live in areas of language contact: Portuguese in Brazil, English in Guyana and Wapixana (another indigenous language). Abbott (1991) describes Macushi as having OVS word order, with SOV word order being used to highlight the subject.[5]

History

editBased on information provided by anthropologist Paulo Santilli for Instituto Socioambiental, the Macuxi people have faced adversity since the 18th century, due to the presence of non-indigenous groups.[2] Located at the frontier of Brazil and Guyana, generations have been forced to migrate from their territory due to the establishment of Portuguese settlements, the influx of extractivists (who came for the rubber) and developers (who came to extract metals and precious stones), and more recently, the insurgence of “grileiros” that counterfeit land titles in order to take over and sell the land. These settlers set up mission villages and farms. Towards the last decades of the 19th century, as the rubber industry boomed and local administration obtained autonomy, the regionals, referring to the merchants and extractivists, advanced the colonial expansion. Subsequently, forced migration continued to occur due to the rise of cattle-raising in the region. Villages were abandoned and escape plans were hatched due to the arrival of the colonizers. To this day, these memories are still preserved in the oral histories of the Macushi people. Since early 20th century, local political leaders have also stepped up to champion for their land rights.

Nowadays, the Macushi territory in Brazil consists of three territorial blocks: Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory (the most extensive and populated), San Marcos Indigenous Territory and small areas that surround isolated villages in the extreme northwest of the Macushi Territory. In the 1970s, Macushi political leaders started to step up, acting as mediators between their indigenous community members as well as the agents of national society. While these areas were officially recognized and demarcated as official indigenous territories in 1993, however, it has not been a smooth road for the Macushi communities. Since then, the Brazilian government has set up school and hospitals for the Macushi community.

Phonology

editConsonants

edit| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Voiceless | p pː |

t tː |

k kː |

ʔ | |||

| Voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | s | ʃ | h | ||||

| Voiced | β | ð | z | ʒ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||

| Approximant | w | j | ||||||

Vowels

edit| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | u |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| ɛ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a |

Nasality also occurs, and is transcribed with a [ã] mark.[6]

The suprasegmental system consists of a high and low or unmarked pitch at the word level”,[7] such as in: átí ‘you go’ and ‘àtí’ ‘he goes’. High pitch is considered the marked pitch, and can be found on the final, penultimate or antepenultimate syllable of the word.

Syntax

editNumerals

editMacuxi numerals precede the noun they modify. When both the demonstrative and numeral occur before the noun, it is irrelevant to the semantic value of the noun. It is also acceptable for the numeral to start a nominal clause.[7]

saki-naŋ

two-NOM-PL

a’anai

cornstalk

yepuupî

skin

imî-rîî-seŋ

ripe-DET-NOM

‘Two ears of corn are ripe.’

saakrîrî-on-koŋ

four-NOM-POSS-PL

ma-ni

those

kanoŋ

guava

'Those four guavas.

Quantifiers

editAccording to Carson, the native numeral system in Macushi is not adequate to express large numbers. The following quantifiers would be used instead:

| Macushi | English |

|---|---|

| tamîmarî | 'all' |

| pampî | 'more/much'

(more as an intensifier) |

| mara-rî | 'little/few' |

| mara-rî-perá | 'several' |

References

edit- ^ Macushi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Macuxi - Indigenous Peoples in Brazil". pib.socioambiental.org. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Crevels, Mily (2012), "Language endangerment in South America: The clock is ticking", The Indigenous Languages of South America, DE GRUYTER, pp. 167–234, doi:10.1515/9783110258035.167, ISBN 9783110258035

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Abbott, Miriam (1991). "Macushi". In Derbyshire, Desmond C.; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (eds.). Handbook of Amazonian Languages. Vol. 3. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 23–160.

- ^ a b Carla Maria Cunha (2004), Um estudo de fonologia da língua Makuxi (karib): inter-relações das teorias fonológicas (PDF) (in Portuguese)

- ^ a b Carson, Neusa M (1981). "Phonology and morphosyntax of Macuxi (Carib)". University of Kansas. Doctoral Dissertation.

External links

edit- Macushi words on Wiktionary by Guy Marco Sr

- Macushi (Intercontinental Dictionary Series)

- A Study of the Phonology of the Macushi Language (PDF) (in Portuguese)

- "Macushi Words (Makushi, Makusi, Macusi)".

- "Colour words in Macushi" (PDF).

- The New Testament in the Macushi Language of Brazil (PDF).