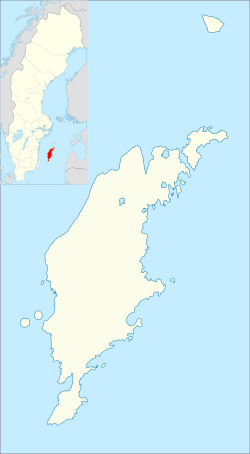

Mästermyr is a, now mostly drained, mire west of Hemse on the island of Gotland, Sweden. The Mästermyr chest was found here in 1936.[1]

Mästermyr | |

|---|---|

mire, cultivated | |

| Coordinates: 57°14′01″N 18°15′00″E / 57.2335°N 18.25°E | |

| Location | Gotland, Sweden |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,670 hectares (6,600 acres) |

| Elevation | 20 m (64 ft) |

Geography

editThe area of the mire was originally 26.7 km2 (10.3 sq mi), of which 3.2 km2 (1.2 sq mi) consisted of small lakes.[2] It was a significant habitat for water birds and the lakes were used for fishing. A suggestion about draining the mire was first presented in 1898.[3] The mire was drained in 1902–10. Some of the lakes that dried up were Tunngansträsk, Storträsk, Nydträsk, Risalaträsk and Eskesträsk.[4]

Just south of the mire is the Havor Iron Age hillfort. At the time it was built, the mire was still lakes and the fort was located on the shore of one of these. In 1961, an archaeological excavation of the hillfort lead to the discovery of the Havor Hoard.[5][6]

History

editAs part of a national program for public works to reduce unemployment in 1920–21, a total of 22.5 km (14.0 mi) of roads were constructed at Mästermyr. By the 1930s, 12 km2 (4.6 sq mi) of the former mire was cultivated.[2]

On 21 April 1940, a German aircraft Heinkel He 111 was forced to make an emergency landing at Mästermyr. It was one of three planes en route to bomb the Steinkjer – Trondheim railway in Norway. Due to cloudy weather they had to abort and return to Aalborg. The navigators had been given faulty information about the prevailing wind conditions and when they broke through the clouds, the planes were over Gotland instead of Skagerrak. Swedish air defence fired on the planes and two of them had to make emergency landings, one at Mästermyr and one at När. The third plane managed to escape and landed on Bornholm.[7]

In 2008, Swedish power company Vattenfall initiated a project to build a wind farm on Mästermyr.[8] The plans were stopped through a decision made by the Swedish Land and Environment Court in July 2012.[9]

References

edit- ^ Arwidsson, Greta; Berg, Gösta (1999). The Mästermyr find. Lompoc, CA: Larson Publishing Company. ISBN 0-9650755-1-6.

- ^ a b Carlquist, Gunnar, ed. (1937). "Mästermyr". Svensk uppslagsbok. Vol. 18. Malmö: Svensk Uppslagsbok AB. pp. 593–94.

- ^ "Förslag till utdikning av Mästermyr". www.riksarkivet.se/. National Archives of Sweden. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Nihlén, John, ed. (1940). Gotland. Svenska turistföreningens resehandböcker, 99-0856560-5 (5 ed.). Stockholm.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "RAÄ-nummer Hablingbo 32:1". www.raa.se. Swedish National Heritage Board. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Nylén, Erik; Lund Hansen, Ulla; Manneke, Peter (2005). The Havor hoard: the gold, the bronzes, the fort. Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. ISBN 9174023454. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Widfeldt, Bo. "Nödlandning på Gotland vid Mästermyr" [Emergency landing on Gotland at Mästermyr]. www.forcedlandingcollection.se. Forcedlanding Collection. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Olsson, Magdalena (30 October 2008). "Samråd om vindkraft på Mästermyr" [Consultation about wind power on Mästermyr]. www.helagotland.se. HelaGotland. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Hjernquist, Anncatrin (12 July 2012). "Ingen vindkraft på Mästermyr" [No wind power on Mästermyr]. www.helagotland.se. HelaGotland. Retrieved 28 October 2015.