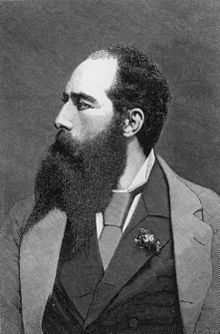

Luigi Maria D'Albertis (21 November 1841 – 2 September 1901) was an Italian naturalist and explorer who, in 1875, became the first Italian to chart the Fly River in what is now called Papua New Guinea. He undertook three voyages up this river from 1875 to 1877. The first was conducted in the steamer SS Ellengowan and the other two in a smaller ship named the "Neva" which was chartered from the Government of New South Wales. Throughout the three voyages, D'Albertis was consistently involved in skirmishes with the various indigenous people living along the river, using rifle-fire, rockets and dynamite to intimidate and, on occasions, kill these local people. He also frequently employed destructive dynamite fishing as a technique of obtaining aquatic specimens for his collection. His expedition stole many ancestral remains, tools and weapons from the houses of the locals. He also collected specimens of birds, plants, insects and the heads of recently killed native people. Contemporary explorers and colonial administrators of d'Albertis were almost universally critical of the methods employed by D'Albertis in his expeditions up the Fly and more modern accounts, such as Goode's "Rape of the Fly" are equally condemnatory.

Luigi Maria D'Albertis | |

|---|---|

Luigi Maria D'Albertis | |

| Born | 21 November 1841 |

| Died | 2 September 1901 (aged 59) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biology |

Early life

editD'Albertis was born in 1841, in Voltri, Italy. At the age of eighteen he joined Garibaldi's army and later joined Odoardo Beccari in November 1871 on an expedition to western New Guinea. He reached the peak of Mount Arfak Geb but was compelled by fever to retreat and return to Sydney to recover. In 1874, D'Albertis returned to New Guinea to set up a base on Yule Island. Here he obtained notoriety for publicly kissing the most attractive young native women and passing it off as a customary sign of peace. He also, with a shell full of burning methylated spirits, ostentatiously threatened to set the ocean alight. Most of his companions and employees deserted him after these activities.[1]

1875 journey up the Fly River

editD'Albertis conducted his first trip to the Fly River in the SS Ellengowan steamer which left from the British colonial port of Somerset on the tip of the Cape York Peninsula. On board were Captain Runcie, Rev. MacFarlane and the Police Magistrate of Somerset, H.M. Chester with six troopers of the Queensland Native Police. Their first stop was Tawan Island where Chester rounded up the inhabitants and warned them against stealing from the missionaries in the area. To emphasise his point, he ordered his troopers to obliterate a nearby termite mound with rounds from their Snider Rifles. As they began to navigate up the Fly River, D'Albertis had a collision with the native people and after shooting a number of rounds at their watercraft, Chester and his troopers dispersed them causing them to flee in terror. As "a trophy of victory", Chester stole a sixty-foot canoe and utilised it for firewood for the ship's engine. At other places along the river D'Albertis set off dynamite and rockets to both intimidate the indigenous people and to obtain aquatic life for food and specimen material. On their return downriver, they accepted an invitation from native people to enter their village, but Chester and his troopers, "wishing to intimidate them" decided to let off a number of shots, killing and stealing a couple of large domesticated pigs. Chester then proceeded to ransack the long-house of the village, taking ancestral and sacred human remains, weapons and other artefacts for D'Albertis' collection.[2]

1876 journey to the Fly River

editD'Albertis' second sojourn to the river was on the "Neva" which was chartered from the Government of New South Wales. On board was Lawrence Hargrave, a future pioneer of aviation. D'Albertis again used rockets and dynamite as a weapons of fear. He removed intricate bark carvings on trees which he recognised was "perhaps a sacrilege" but did it anyway. Likewise, he stole ancestral bones from sacred long-houses claiming that "I shall turn a deaf ear to this sacrilege..I am too delighted with my prize". The Neva forced its way upstream until brought to a halt by the shallows. They then steamed downriver to a tributary d'Albertis had named the Alice River (today known as the Ok Tedi). Eventually stricken by malaria and crippled by rheumatism in both legs, he admitted defeat and returned to the Torres Strait.[3]

1877 journey to the Fly River

editThis was the final and probably the most eventful of the journeys of D'Albertis up the Fly River. On the first day of June, D'Albertis managed to get his crew and himself involved in a pitched battle with an armed flotilla of native watercraft. D'Albertis himself claimed to have fired about 120 shots in this skirmish which resulted in "some deaths" of indigenous people. None of his crew were killed but the hull of the "Neva" was riddled with arrows, some of which penetrated through the boards. For most of early July, D'Albertis was involved in daily clashes with native people along the river, shooting some of them dead. On one occasion, D'Albertis found the corpse of one of those killed and decided to decapitate him and preserve the head in spirits for his collection. He later killed one of his Chinese servants for refusing to go into the jungle to shoot specimens of local fauna. D'Albertis killed him by hitting him on the back a number of times with a bamboo cane which broke during the punishment. The other Chinese servants subsequently fled into the jungle, preferring to take their chances in unknown territory than to stay with the expedition.

Returning downriver in late October, D'Albertis again had several affrays with indigenous people killing at least seven. In one of these battles, D'Albertis decided to "let them have it, and their blood be on their own heads". After this encounter he became extremely wary, ordering every native canoe to be shot at on sight. During this trip, as with the others, D'Albertis regularly engaged in dynamite fishing, claiming that "I think dynamite is..the best means to use, especially among coral reefs". Once back in the Torres Strait, two other deserters from his expedition brought charges against D'Albertis for murdering his Chinese servants.[4] The police magistrate, H.M. Chester, a colleague of D'Albertis, promptly dismissed the charges and jailed the two Polynesian men for 16 weeks under charges of mutiny. D'Albertis wanted the men executed, but begrudgingly accepted the sentence.[5]

Not long after, D'Albertis returned to Europe with his bounty of stolen goods. His cousin, fellow explorer Enrico Alberto d'Albertis, housed many of Luigi's specimens at Castello D'Albertis. The castle is now home to the Museum of World Cultures. His natural history specimens from New Guinea are in the Natural History Museum of Giacomo Doria in Genoa.

Criticisms and influences

editLater colonial administrators of British New Guinea such as Peter Scratchley, William MacGregor and John Hubert Plunkett Murray were critical of the methods employed by D'Albertis. Although these directors themselves engaged in various repressive and punitive policies against the native peoples, they recognised that the techniques of D'Albertis were very harmful in facilitating British colonisation.[6] Andrew Goldie, an early British prospector to New Guinea, described an incident at a dinner in Sydney with D'Albertis where after having a steak accidentally thrown at him, the Italian "foamed with rage" and standing up in the restaurant with a bottle in his hand threatened to smash the skull of whoever owned up to being the thrower.[7]

D'Albertis however was not the first or last to implement such irresponsible plundering actions on the Fly and nearby rivers. Captain Blackwood, in 1846, of HMS Fly (after which the river is named) engaged in unapologetic raiding of villages on the river, including bombardment their houses.[8] Also, a few years after D'Albertis' voyages, Captain John Strachan made an expedition up the nearby Mai Kussa river which was even more destructive than the Italian's. Strachan, who seems to have been in a chronic state of irrational paranoia and insomnia, improvised a torpedo-like weapon against a convey of native canoes causing a large amount of damage and number of casualties. In a high state of anxiety, Strachan later had to abandon his vessel and return to the coast on foot, committing massacres of indigenous people along the way. Strachan was later accused of being a "red-handed murderer who had tramped knee-deep in blood through New Guinea". He applied for protection from Lord Derby and subsequently no charges were laid.[9]

Eponyms

editA number of reptile species from New Guinea were named in honour of d'Albertis, but most have subsequently become synonyms of other species.

- Gonyocephalus (Lophosteus) albertisii W. Peters & Doria, 1878, now Hypsilurus papuensis (Macleay, 1877) (Papuan forest dragon)

- Heteropus Albertisii W. Peters & Doria, 1878, now Carlia bicarinata (Macleay, 1877) (bicarinate grassland skink)

- Liasis albertisii W. Peters & Doria, 1878, now Leiopython albertisii (W. Peters & Doria, 1878) (northern white-lipped or d’Albertis python)[10]

- Emydura albertisii Boulenger, 1888, now Emydura subglobosa (Krefft, 1876) (red-bellied short-necked turtle)[10]

Only the python carries d’Albertis’ name today.

Several of these species were described by the German naturalist Wilhelm Peters and Giacomo Doria, the Italian naturalist and founder of the Natural History Museum of Giacomo Doria.

Only Leiopython albertisii (the white-lipped python) is currently recognised as a valid species, the other three reptiles being synonymised within species described earlier, ironically two of which were described by entomologist Sir William John Macleay whose rival expedition on the Chevert,[11] was also collecting specimens in southern Papua.

The beetle Bironium albertisi Löbl, 2021, is named after D'Albertis, "one of the early explorers of the fauna of New Guinea and Moluccas".[12]

The plant genus Albertisia Becc. (1877) is also named after him.

Publications

edit- "Journeys up the Fly River and in other parts of New Guinea". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 1879: 4-16 (including map). (read at the Evening Meeting, November 11, 1878).

- New Guinea: What I Did and What I Saw. Vol. I and II. London: S. Low Marston Searle & Rivington, 1880.

References

edit- ^ Gibbney, H.J. "Luigi Maria D'Albertis". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ D'Albertis, Luigi (1880). New Guinea: what I did and what I saw. Vol II. London: Sampson Low. pp. 1-40.

- ^ D'Albertis, Luigi (1880). New Guinea: what I did and what I saw. Vol II. pp. 45-205.

- ^ Maria Johanna van Steenis-Kruseman (1950). "Cyclopaedia of collectors". Flora Malesiana. 1 (1): 9. ISSN 0071-5778. Wikidata Q108384933.

- ^ D'Albertis, Luigi (1880). New Guinea: what I did and what I saw. pp. 213-360.

- ^ Murray, J.H.P. (1912). Papua or British New Guinea. London: Fisher Unwin. pp. 256-260.

- ^ Bevan, T.F. (1890). Toil, travel and discovery in British New Guinea. London: Kegan Paul. p. 19.

- ^ Jukes, J.B. (1847). Surveying voyage of H.M.S. Fly. London: Boone.

- ^ Strachan, John (1888). Explorations and adventures in New Guinea. London: Sampson Low.

- ^ a b Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("D'Albertis", p. 64).

- ^ Office, Publications. "Chevert". sydney.edu.au.

- ^ Ivan Löbl (2021). "A review of the Bironium Csiki, 1909 (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae: Scaphidiinae) of New Guinea and the Moluccas" (PDF). Acta Musei Moraviae, Scientiae Biologicae. 106 (2): 227–248. ISSN 1211-8788. Wikidata Q109601493.

External links

edit- Edwards, Ian. Luigi D'Albertis 1841-1901

- Kirksey, E. Anthropology and Colonial Violence in West Papua. Cultural Survival Quarterly, Fall 2002.

Further reading

edit- Goode, John (1977). Rape of the Fly: Explorations in New Guinea. Melbourne: Nelson. viii + 272 pp.