The Lugares colombinos ("Columbian places") is a tourist route in the Spanish province Huelva, which includes several places that have special relevance to the preparation and realization of the first voyage of Cristopher Columbus. That voyage is widely considered to constitute the discovery of the Americas by Europeans. It was declared a conjunto histórico artístico ("historic/artistic grouping") by a Spanish law of 1967.[1]

There are two localities so honored: Palos de la Frontera (both the old center and the La Rábida Monastery 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) distant), and Moguer. Columbus visited each of these places several times, and people associated with each played roles in his voyage. He received help and collaboration for his projected voyage from the brothers of the La Rábida Monastery, the Pinzón Brothers of Palos de la Frontera, the Niño Brothers of Moguer and other prestigious families of mariners in the area who were further distinguished by their participation in the voyage of discovery.

In the years following Columbus's voyage this area of Spain, especially Palos, suffered a great economic decline, owing in part to emigration to the newly discovered territories overseas. The recuperation of the historical importance of this region with respect to the Spanish discovery and conquest of the Americas (and the interest in preserving and restoring the buildings associated with Columbus) began, in part, with the nineteenth-century writer Washington Irving, from the United States, whose travels in Spain included this area. His diary entries for 12–14 August 1828 deal with the Lugares colombinos; that same year he would publish A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus; he also published a short essay about Palos as an appendix to Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus.

The Lugares colombinos remain a strong reminder of the history linking Spain to Latin America, and are the most noted historical and cultural sites in the province of Huelva.

Palos de la Frontera

editPalos

editPalos de la Frontera describes itself as the "cradle of the Discovery of America". The royal provision undertaking to provide two caravels for Columbus was read out at the fourteenth century Church of Saint George the Martyr (Iglesia de San Jorge Mártir) on 30 April 1492.[2] It was declared a National Monument in 1931.

Near this church is the Fontanilla, the public fountain from which, according to tradition, Columbus's boats drew the fresh water for their voyage. The fountain lay between the church's Puerta de los Novios[3] and the wharf from which Columbus's expedition departed. The base of the fountain dates back to Roman times and it is protected by a tetrapylum, a sort of gazebo, constructed of stone in the thirteenth century[4] in the Mudéjar style.

The Pinzón Brothers (Martín Alonso Pinzón, Vicente Yañez Pinzón, and Francisco Martín Pinzón), co-discoverers of America, were from Palos. The oldest, Martín Alonso, played a decisive role in the voyage. His prestige as a shipowner and marine expert encouraged the mariners throughout the district; he also put up one third of the cost of the voyage and, rejecting the first ships provided for Columbus, obtained others that were more appropriate.[5] The house of the brothers, also, in Palos, is now the Casa Museo de Martín Alonso Pinzón, and conserves its fifteenth century façade and part of its original flooring.

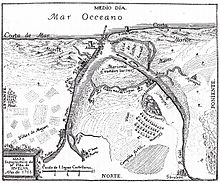

One can also walk along the banks of the Rio Tinto near the Calzadilla wharf from which the Plus Ultra flying boat took off on the first Trans-Atlantic flight between Spain and South America in January 1926. Quite near that is the historic port of Palos—now disappeared because of decreased river flow and silting—and the old rural road leading to La Rábida.

La Rábida

edit3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the city center, near the mouth of the Río Tinto, stands the Franciscan monastery of Santa María de La Rábida (14th-15th century), where in 1485 Christopher Columbus arrived for the first time with his son Diego, tired and dispirited after his failure with John II in the Portuguese court.

In this small monastery he met with hospitality, help, and support, especially on the part of two monks. Fray Juan Pérez, guardian of the monastery, had served in the court of Spain as a clerk and confessor and Fray Antonio de Marchena, custodian of the monastery and a famous astrologer (a role that had not yet been fully disentangled from that of an astronomer), had also been a councilor in that court. Both of these monks gave Columbus support at court and helped him to secure the crews he needed. The convent was a place of refuge and of development and promulgation of Columbus's ideas, especially given that the sciences at that time were largely the work of the religious orders.[6][7]

The church is of artistic interest for its Gothic-Mudéjar architecture, as well as the grand rooms decorated with frescos by Daniel Vázquez Díaz, the cloister, and the museum, which holds numerous objects commemorating the discovery of America.[8] Above all, there is the namesake of the monastery, the fourteenth century statue known as the Virgin of Miracles or Saint Mary of La Rábida. It is an elegant example of Gothic Mannerism, bringing the figure a particular curvature, such that it changes in aspect from even small differences of perspective. Columbus and his men prayed before this figure the night before their departure. The statue was crowned by Pope John Paul II 14 June 1993.[9][10] It is the only image of the Virgin Mary that John Paul crowned in Spain.

The Monastery was declared a National Monument in 1856.[11] It was declared the "First historical monument of the Hispanic peoples" (Primer Monumento histórico de los pueblos Hispánicos) in 1949.[12] On 28 February 1992, the Andalusian Autonomous Government awarded the monastery the "Gold Medal of Andalusia".[13] At the Ninth Ibero-American Summit (Havana, 1999) the Heads of State and Presidents of Government recognized La Rábida as the site of the Forum of the Organization of Ibero-American States.[14]

Near La Rábida is the Wharf of the Caravels (Muelle de las Carabelas) a museum installation with reproductions of Columbus's ships, the Santa María, La Niña, and La Pinta.

Moguer

editOn several occasions, Columbus visited the fourteenth century Santa Clara Monastery in Moguer, a convent of the Poor Clares. The abbess, Inés Enríquez, was the aunt of King Ferdinand II, and supported Columbus's projected voyage before the court.

Notable features of the monastery are the Mothers' Cloister (claustro de las Madres), whose fourteenth century lower floor siglo XIV, reminiscent of Almohad architecture, is the oldest surviving cloister of a convent or monastery in Spain; the infirmary, a two-story sixteenth century Renaissance building with Genovese columns; and the convent church, with three naves and a polygonal apse. The main altar has an altarpiece carved in 1642 by Jerónimo Velázquez, and the fourteenth century choir has Spain's only surviving Nasrid choir stalls.[15] The monastery was declared a National Monument in 1931. Next to the monastery is the Columbus Monument.

Columbus and his men passed the first night after returning from his first voyage of discovery in this church,[16] thereby fulfilling a vow they had made on the high seas when a storm was on the point of capsizing the caravel Niña,[17][18] which he captained on the return voyage from America after the wreck of the Santa María.

In Moguer, Columbus also received support from cleric Martín Sánchez[citation needed] and landowner Juan Rodríguez Cabezudo, to whom he confided the custody of his son Diego during his first voyage.[19]

One of the provisions that Columbus received from the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel was support from the towns of the Andalusian coast in assembling his three caravels.[20] By means of a commission directed to the town of Moguer to fulfill this provision,[21] he seized two boats in this locality in the presence of the notary Moguer Alonso Pardo, boats that were later discarded by Martín Alonso Pinzón.

The caravel Niña was built in the shipyards of Moguer's puerto de la ribera around 1488, and was property of the Niño Brothers, who also played an important role in recruiting and preparing local mariners for Columbus's expedition.

Today, Moguer is also known as the birthplace of the poet Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958), winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1956, perhaps best known for his prose work Platero y yo (1917; "Platero and I"). An eighteenth-century house in which he lived from the age of 2 into adulthood is now a museum, the Casa Museo Zenobia y Juan Ramón Jiménez, as is his birthplace—the nineteenth-century Casa Natal Juan Ramón Jiménez—and his nearby country house Fuentepiña.[22]

Washington Irving rediscovers the Lugares colombinos

editAmong the prolific works of the nineteenth-century American writer Washington Irving are several with a bearing on the Lugares colombinos: his diary entries for 12–14 August 1828 when he visited the area; portions of A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus; and "A visit to Palos", an appendix to Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus. His 1828 diaries provide a useful record of the state of the Lugares colombinos before deliberate preservation and restoration began and also relate his contact with the descendants of the Pinzón Brothers in that era, but far more than that, his work played a determining role in making the world aware of the Lugares colombinos and in recovering their history. His works gave worldwide renown to Palos de la Frontera, La Rábida, Moguer, The Pinzón Brothers, Fray Juan Pérez, and so forth as protagonists of the discovery of the Americas.

In 2001, on the occasion of the annual 12 October celebration of the discovery of America, the Provincial Deputation of Huelva officially recognized Irving's role in rescuing the memory of this history and broadcasting it throughout the world.[23]

Access

editAfter the Lugares colombinos first became tourist destinations, travellers came on small boats through the estuary of Huelva or on the old Huelva-Seville highway (now the A-472) which passes through nearby San Juan del Puerto. In the 1970s, the area began to industrialize, and a bridge was constructed over the Huelva estuary, linking the capital (the city of Huelva) to the beaches of Mazagón and to the Lugares colombinos.

Today, the main roads into the area are:

- From Huelva capital: by the H-30, N-442, and H-624 to La Rábida (10 kilometres (6.2 mi)) and to Palos de la Frontera (10 kilometres (6.2 mi)); by the H-30, A-49 (in the direction of Seville) and A-494 to Moguer (20 kilometres (12 mi)).

- From the province of Seville: by the A-49 (in the direction of Huelva) and A-494 to Moguer (86 kilometres (53 mi)), thence to Palos de la Frontera (93 kilometres (58 mi)) and La Rábida (96 kilometres (60 mi)).

Notes

edit- ^ BOE nº 69 de 22 March 1967. "Decreto 553/1967, de 2 de marzo, por el que se declara conjunto histórico artístico el sector denominado "Lugares Colombinos" en la provincia de Huelva" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Real Provisión de los Reyes Católicos que fue enviada a Diego Rodríguez Prieto y otros compañeros, vecinos de la villa de Palos, a fin de que tuvieran preparadas dos carabelas para partir con Cristóbal Colón Granada, 30 de abril de 1492. Archivo General de Indias. Signatura: PATRONATO, 295, N.3. (in Old Spanish).

- ^ A door of the church. Novios does not translate easily in this context; it means a couple in love, and can variously mean anything from people who are dating to newlyweds. So, roughly, "Lovers' Door," but with no suggestion of anything illicit.

- ^ Izquierdo Labrado, Julio (1987). Palos de la Frontera en el Antiguo Régimen (1380-1830). Huelva: Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana / Ayuntamiento de Palos de la Frontera.

- ^ (1) Diputación de Huelva. "Los marineros de Huelva". Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- (2) Ortega, Ángel (1925). La Rábida. Historia documental crítica. 4 vol. (Ed. facsímil). Vol. 3. Diputación Provincial de Huelva. Servicio de Publicaciones. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-84-500-3860-6.

- (3) Morales Padrón, Francisco (1961). Las relaciones entre Colón y Martín Alonso Pinzón. in: Actas. Vol. 3. Lisboa. pp. 433–442.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - (4) Manzano y Manzano, Juan; Manzano Fernandez-Heredia; Ana Maria (1988). Los Pinzones y el Descubrimiento de América. 3 volumes. Madrid: Ediciones de Cultura Hispanica. ISBN 978-84-7232-442-8.

- (5) Íñiguez Sánchez-Arjona, Benito (1991). Martín Alonso Pinzón, el calumniado. Sevilla: Imp. José de Haro. ISBN 978-84-604-1012-6.

- ^ Biografía de Cristóbal Colón, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed online 2007-12-18.

- ^ Biografía de Cristóbal Colón Archived 27 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, www.artehistoria.jcyl.es. Accessed online 2007-12-18.

- ^ Monasterio de Santa María de La Rábida Archived 1 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Diputación de Huelva. Accessed online 2007-12-18.

- ^ Cuarto viaje apostólico a España Archived 13 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Spanish Council of Bishops, 1993. Accessed online 2007-12-10.

- ^ El Papa en los Lugares colombinos Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, planalfa.es. Accessed online 2007-12-10.

- ^ Expediente sobre la declaración de Monumento Nacional al Monasterio de Santa María de la Rábida, especially Minuta de oficio en la que se comunica que la Real Academia de la Historia cree que el Monasterio de la Rábida ya fue declarado Monumento Nacional por Real Orden de 23 de febrero de 1856, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed online 2010-01-05.

- ^ I Congreso Hispanoamericano de Historia. Madrid, October 1949.

- ^ "DECRETO 31/1992, de 25 de febrero, por el que se concede la Medalla de Andalucía, a la Fundación Franciscana de La Rábida" (in Spanish). BOJA. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ IX Cumbre Iberoamericana, Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos. Accessed online 2010-01-05.

- ^ González Gómez, Juan Miguel (1978). El Monasterio de Santa Clara de Moguer. Huelva: Diputación de Huelva. ISBN 978-84-00-03752-9.

- ^ Moguer y América, www.aytomoguer.es (official site of Moguer). Accessed online 2010-01-08.

- ^ Christopher Columbus and Bartolomé de las Casas, Samuel Kettell (translator), Personal narrative of the first voyage of Columbus to America: From a manuscript recently discovered in Spain, T. B. Wait and Son, 1827. p. 216. Online at Google Books.

- ^ Text for 11-16 February Archived 14 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, accessed online at artehistoria.jcyl.es.

- ^ John Boyd Thacher, Christopher Columbus: His Life, His Works, His Remains: As Revealed by Original Printed and Manuscript Records, Together with an Essay on Peter Martyr of Anghera and Bartolomé de Las Casas, the First Historians of America, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1904, p. 620n. Online at Google Books.

- ^ Real cédula notificando a las ciudades y villas que mandan a Colón con tres carabelas a ciertas partes del mar, y que le ayuden.

...las cibdades e villas e logares de la costa de la mar de Andalucía como de todos los nros. reynos e Señorios (...) Sabedes que nos habemos mandado a Christobal Colon que con tres carabelas vaya a ciertas partes de la mar oceana como nro. capitan (...) por ende nos vos mandamos a todos e a cada uno de vos en vros. logares e jurisdicciones que cada quel dicho Christobal Colon hobiere menester....

— Archivo General de Indias. Signatura: PATRONATO, 295, N.4. - ^ Comisión al contino Juan de Peñalosa, para que haga cumplir en la villa de Moguer, una cédula de SS. AA., ordenando se entreguen a Cristóbal Colón, donde y cuando las pidiese, tres carabelas armadas y equipadas. Archivo General de Simancas. Signatura: RGS,149206,1

- ^ fundación-jrj.es. "Fundación Juan Ramón Jiménez". Moguer, Spain. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Washington Irving, Biógrafo de Colón y Descubridor de los Lugares Colombinos, Diputación Provincial de Huelva. That page is no longer online, but it can be accessed on the Internet Archive in the version of 2008-02-02.