This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Louisiana pine snake (Pituophis ruthveni) is a species of large, non-venomous, constrictor in the family Colubridae.[3][4] This powerful snake is notable because of its large eggs and small clutch sizes. The Louisiana pine snake is indigenous to west-central Louisiana and East Texas, where it relies strongly on Baird's pocket gophers for its burrow system and as a food source. The Louisiana pine snake is rarely seen in the wild, and is considered to be one of the rarest snakes in North America. The demise of the species is due to its low fecundity coupled with the extensive loss of suitable habitat - the longleaf pine savannas in the Gulf coastal plain of the southeastern United States. Management activities are being conducted to promote the species' recovery.

| Louisiana pine snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Pituophis |

| Species: | P. ruthveni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pituophis ruthveni Stull, 1929

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

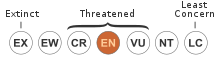

Recovery efforts to counter extirpation resulted in around 300 snakes having been reintroduced into the wild. In 2018 the snake was added to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. A species-specific rule on 27 February 2020, means interfering with the species could result in criminal charges.

Taxonomy and etymology

editThe species was first described by Olive Griffith Stull in 1929 as a subspecies of P. melanoleucus. In 1940, the Louisiana pine snake was promoted to the rank of species in another of Stull's articles. Its scientific name honors Alexander Grant Ruthven, the late herpetologist of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.[5]

Description

editDorsally, the color is buff or lion-like yellow with dark brown blotches and spots that are very similar throughout the body.[6] The marking patterns are visibly different from one end to another. The neck region is "busier", the dark reticulates and blends more with the lighter coloration. Towards midbody, the dark markings become more distinct and contrasting, and continue to be more distinct toward the tail, yet reduced in marking thickness. These markings number 28-42 middorsally. Furthermore, the very pointed head may only be marked slightly with some small dots and a faded bar in front and between the orbitals above. The ventrals never appear to be immaculate, but are intermediately blotched with brown. Nevertheless, there usually is no true checkered pattern. The rostral scale is exceptionally large, and usually 8 or 9 supralabials and from about 10-15 (generally 14) infralabials are present.

Growth and reproduction

editGrowth is rapid; snakes may reach 2–3 ft (61–91 cm) in total length at 1 year and 3–4 ft (91–122 cm) at 2 years. The largest reported specimen was 5.8 ft (180 cm) in total length. Sexual maturity may be attained at a minimal total length of 4 ft (120 cm) and an age of at least 3 years. The species is oviparous, with a gestation period around 21 days, followed by 60 days of incubation. This species exhibits a remarkably low reproductive rate, which magnifies other threats to the Louisiana pine snake. It has the smallest clutch size (three to five) of any North American colubrid and the largest eggs, generally 5 in (13 cm) long by 2 in (5.1 cm) wide, of any snake in the United States. It also produces the largest hatchlings reported for any North American snake, ranging 18–22 in (46–56 cm) in total length, and up to 0.8 oz (23 g) in weight. The large size of the pine snake hatchlings may be an adaptation to enable young to feed relatively early.

Behavior

editIn studies in East Texas and western Louisiana, the snakes spent at least 60% of their time below ground, exhibiting only short-range movements of 10–20 ft (3.0–6.1 m). Snakes were most active late morning and midafternoon, and least active at night and early morning. Above ground, snakes usually moved underground at least once during the day, possibly for foraging, body cooling, or predator avoidance. Hibernation sites were always within pocket gopher burrow systems.

Seasonally, Louisiana pine snakes were most active March–May and fall (especially November) and least active during hibernation in December–February, and in summer (especially August). Their below-ground refuges were almost exclusively Baird's pocket gopher (Geomys breviceps) burrow systems. Pocket gophers also appear to be their primary food source, but other reported food items include other rodents, cottontails, amphibians, and ground-nesting birds and eggs.

Their annual home range varied from 12 acres (4.9 ha) (juveniles) to 195 acres (79 ha) in size, and averaged 69 acres (28 ha). Adult males had larger home ranges (145 acres (59 ha)) than females covering 25 acres (10 ha)). Pine snakes in East Texas usually moved less than 33 ft (10 m) daily. However, when snakes did move longer distances, usually from one pocket gopher burrow system to a new one, the average daily distance moved was 669 ft (204 m) for adult females and 568 ft (173 m) for adult males; in Louisiana, males moved an average of 492 ft (150 m), and females 344 ft (105 m). Males tended to make long moves in May–July, while females moved primarily in July–September. Seasonal migration was not indicated.

Habitat

editThe Louisiana pine snake is generally associated with sandy, well-drained soils; open pine forests, especially longleaf pine savannas; moderate to sparse midstory; and a well-developed herbaceous understory dominated by grasses. Its activity appears to be heavily concentrated on low, broad ridges overlain with sandy soils. Baird's pocket gophers appear to be an essential component of their habitat. They create the burrow systems in which the pine snakes are most frequently found, and serve as a major source of food for the species. Up to 90% of radio-tagged snake relocations have been underground in pocket gopher burrow systems, and movement patterns are typically from one pocket gopher burrow system to another. Snakes disturbed on the surface retreated to nearby burrows, and hibernation sites were always within burrows. Both native and captive-released snakes were found most frequently in areas containing an ample number of pocket gopher mounds, and snakes stayed active longer and moved greater distances where pocket gopher burrows were abundant.

Pocket gopher abundance is dependent upon an abundance of herbaceous groundcover and loose, sandy soils. The amount of herbaceous vegetation is related to canopy cover. Generally, a rich ground layer requires a high degree of solar penetration into the forest floor. Pocket gopher abundance was associated with a low density of trees and an open canopy, which allowed greater sunlight, more understory growth, and better forage.

Distribution and status

editLouisiana pine snakes originally occurred in at least 9 Louisiana parishes and 14 Texas counties, coinciding with a disjunctive portion of the longleaf pine ecosystem west of the Mississippi River. They are now found in only four Louisiana parishes, and at most, five Texas counties. In Texas, recent records confirm their presence only in the southern portion of the Sabine National Forest (Sabine County) and adjacent private land (Newton County), and in the southern portion of Angelina National Forest and adjacent private timberland (Angelina, Jasper, Tyler Counties). Most Louisiana records originate in Bienville Parish on privately owned forestland. A second population occurs on federal lands in Vernon Parish (Fort Johnson, U.S. Army, and Kisatchie National Forest). An apparent third population has been found near the junction of Vernon, Sabine, and Natchitoches Parishes.

The extensive population declines and local extinctions of the Louisiana pine snake have occurred during the last 50–80 years. A habitat assessment of known historical localities found that only 34% were still considered capable of supporting a viable population of pine snakes. The species has not been documented in over a decade in some of the best remaining habitat within its historical range, suggesting extinction or extreme rarity. It is now recognized as one of the rarest snakes in North America, and one of the rarest vertebrate species in the United States.

Threats

editHabitat loss

editUrban development, conversion to agriculture, road construction, and mining have all contributed to loss and fragmentation of pine snake habitat. Direct human predation and collection for the pet trade may have also impacted populations. However, the greatest impact to populations has been loss of the native longleaf and shortleaf pine ecosystems. Virtually all timber in the South was cut during intensive commercial logging from 1870 to 1920. In 1935, only 3% of remaining longleaf pine forests in Louisiana and Texas existed as uncut, old-growth stands. In the 1980s, only 15% in Louisiana and 7% in Texas of the 1935 levels of natural longleaf pine forest still remained. The majority of this historic longleaf and shortleaf pine savanna forests has been replaced with plantations of fast-growing loblolly and slash pine. These commercial plantations are typically grown in very dense, closed-canopy stands that are harvested on short rotations less than 40 years. These forests have sparse and poorly structured understory plant communities, rendering them uninhabitable for pocket gophers.

Fire suppression

editAny remaining pine habitat occurs in isolated blocks and is often degraded by the lack of periodic wildfires. The suppression of natural fire events may represent the greatest threat to the Louisiana pine snake in recent years, decreasing both the quantity and quality of habitat available to pine snakes. The longleaf pine savanna forest evolved as a fire climax community, adapted to the occurrence of frequent, but low-intensity, ground fires. These natural fire events on sandy, well-drained soils typically maintained an overstory dominated by longleaf pine, with minimal midstory cover, but a well-developed understory of native bunch grasses and herbaceous plants. These park-like forests supported ideal habitat for pocket gophers, and subsequently, pine snakes.

In the absence of periodic fires, these upland pine savanna ecosystems rapidly develop a dense midstory which suppresses or eliminates any herbaceous understory. Since the presence of pocket gophers is directly related to the extent of herbaceous vegetation available to them, their population numbers and distribution declines as such vegetation declines. No pine snakes have been captured in areas substantially degraded by fire suppression. Pine snakes are well adapted to fire. Aboveground snakes quickly move into pocket gopher burrows as flames come near. Nine pine snakes residing in areas subjected to prescribed burns over three years' time all survived with no damage.

Vehicle mortality

editLouisiana pine snakes are also affected by vehicle-caused mortality, both on state roads and on off-road trails. Researchers documented the loss of three snakes to vehicle traffic, including off-road vehicles. Roads with moderate to high traffic levels can reduce populations of large snakes by 50-75%, up to 2,800 ft (850 m). Known conflicts between pine snakes and motorized vehicles exist in sections of the Longleaf Ridge Area of Angelina National Forest. Motorized vehicles have eliminated a large part of the Millstead Branch bog community and the Catahoula Barrens community. In Sabine National Forest, vehicle conflicts occur on Foxhunter's Hill and the Stark Tract.

Recovery effort

editSpecies with low reproductive rates, like the Louisiana pine snake, are typically incapable of quickly recovering from events that affect population size, increasing their potential for local extinctions. Survival of the Louisiana pine snake depends on that of Baird's pocket gopher, whose abundance, in turn, depends on the understory plants and loose, sandy soil of the longleaf pine savannas. In March 2004, eight state and federal agencies signed a landmark Candidate Conservation Agreement to protect the Louisiana pine snake on federal lands in Texas and Louisiana.[7] Organizations participating in the effort include Fort Johnson Military Installation, Kisatchie National Forest, National Forests in Texas, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, United States Fish and Wildlife Service's Southeast and Southwest regions, and United States Forest Service's Southern Research Station. The voluntary agreement provides a way for the agencies to collaborate on projects to avoid and minimize impacts to the snake. The agreement also sets up a mechanism to exchange information on successful management practices and to coordinate research efforts. Fire is central to the recovery effort.

The management actions proposed by the partners in the agreement are designed to restore and protect the remaining longleaf pine forests of East Texas and western Louisiana. Frequent, low-intensity ground fires are required to maintain the open midstory of these forests; many of the plants must literally be burnt to reproduce or grow. Longleaf pine forests are very special habitats, being among the most biologically diverse ecosystems outside the tropics. Over 30 plant and animal species associated with longleaf pine ecosystems are endangered or species of concern.

The American Zoo and Aquarium Association manages a Species Survival Plan for the Louisiana pine snake, headquartered at the Memphis Zoo. The Species Survival Plan insures that the precious captive population maintained in zoos, which sits precariously at less than 100 individuals, is managed wisely and for the long term.

Reintroduction of captive snakes has resulted in around 300 being released into the wild. The Fish and Wildlife Service placed the Louisiana pine snake on the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife as a result of a final rule on 7 May 2018. A species-specific 4(d) rule means interfering with the species could result in criminal charges.[8][9]

References

edit- ^ Hammerson, G.A. (2007). "Pituophis ruthveni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T63874A12723685. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T63874A12723685.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Pituophis ruthveni". NatureServe Explorer An online encyclopedia of life. 7.1. NatureServe. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "US Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region 2, Clear Lake Ecological Service Field Office, Houston, TX: Louisiana pine snake" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "Candidate Conservation Agreement for the Louisiana pine snake". Fws.gov. 1994-01-25. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Pituophis ruthveni, p. 230).

- ^ "Briggs, Patrick H. Louisiana pine snake". Freewebs.com. 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Rare Pine Snake Needs Fire to Survive". Srs.fs.usda.gov. 2004-05-04. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "Conserving Louisiana's Elusive Pinesnake". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status for Louisiana Pinesnake" (PDF). Department of the Interior Federal Register listing. 2018-04-06. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

Further reading

edit- Stull OG (1929). "The description of a new subspecies of Pituophis melanoleucus from Louisiana". Occ. Papers Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan (205): 1-3. (Pituophis melanoleucus ruthveni, new subspecies). hdl:2027.42/56644

- Stull OG (1940). "Variations and relationships in the snakes of the genus Pituophis ". Bull. United States Natl. Mus. (175): 1-225. hdl:10088/10216

Additional on-line resources

edit- Himes, John G.; Hardy, Laurence M.; Rudolph, D. Craig; Burgdorf, Shirley J. (2002). "Growth rates and mortality of the Louisiana pine snake (Pituophis ruthveni)". Journal of Herpetology 36 (4): 683-687.

- Himes, John G.; Hardy, Laurence M.; Rudolph, D. Craig; Burgdorf, Shirley J. (2006). "Movement patterns and habitat selection by native and repatriated Louisiana pine snakes (Pituophis ruthveni): implications for conservation". Herpetological Natural History 9 (2): 103-116.

- Rudolph, D. Craig; Burgdorf, Shirley J. (1997). "Timber rattlesnakes and Louisiana pine snakes of the west Gulf Coastal Plain: hypotheses of decline". Texas J. Sci. 49 (3) Supplement: 111-122.

- Rudolph, D. Craig; Burgdorf, Shirley J.; Conner, Richard N.; et al. (2002). "Prey handling and diet of Louisiana pine snakes (Pituophis ruthveni) and black pine snakes (P. melanoleucus lodingi), with comparisons to other selected colubrid snakes". Herpetological Natural History 9 (1): 57-62.

- Rudolph, D. Craig; Burgdorf, Shirley J.; Schaefer, Richard R.; Conner, Richard N.; Maxey, Ricky W. (2006). "Status of Pituophis ruthveni (Louisiana Pine Snake)". Southeastern Naturalist 5 (3): 463–472.

- Handwerk, Brian (2004). "Rare, 'Weird' Snake Survives in Louisiana". National Geographic News.