The Llanos de Moxos, also known as the Moxos plains, are extensive remains of pre-Columbian agricultural societies scattered over the Moxos plains in most of Beni Department, Bolivia. The remains testify to a well-organized and numerous indigenous people.[1] This contradicts the traditional view of archaeologists, notably Betty Meggers, who asserted that the Amazon River Basin was not environmentally able to sustain a large population and that its indigenous inhabitants were hunter-gatherer bands or slash-and-burn farmers. In the 1960s, petroleum company geologists and geographer William Denevan were among the first to publicize the existence of extensive prehistoric earthworks constructed in the Amazon, especially in the Llanos de Moxos.

A large part of the Llanos de Moxos is covered with water during the rainy season. Many types of earthworks have been documented in the Llanos, including monumental mounds, raised fields for agriculture, natural and constructed forest islands, canals, causeways, ring ditches, and fish weirs. Archaeological investigations in the Llanos have not been extensive and many questions remain about the cultures of the prehistoric inhabitants. To date, there is no evidence that the inhabitants were politically united in pre-Columbian times, but rather they seem to have been organized into a large number of small, independent polities speaking a variety of different, unrelated languages. Lidar data reported in 2022 may reveal much about sites that have not been investigated. This may help to establish a clearer understanding of these prehistoric cultures.

Evidence of people living in the Llanos dates back to 8000 BCE. Archaeologists have found artifacts in the monumental mounds dating to as early as 800 BCE. The Llanos were heavily populated by indigenous people until the arrival of the Spanish in the late 17th century.

Environment

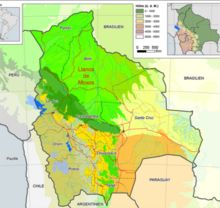

editDiffering definitions of the area comprising the Llanos de Moxos in northern Bolivia result in estimates of their size ranging from 110,000 square kilometres (42,000 sq mi) to 200,000 square kilometres (77,000 sq mi).[2] This area is characterized by flat terrain, many rivers and shallow lakes, and a tropical climate with pronounced wet and dry seasons. Fifty to sixty percent of the land is flooded from four to ten months per year.[3] The Llanos are located mostly in the drainage basin of the Mamoré River.

The main contemporary urban center in the Llanos is the present-day city of Trinidad. East of that city is Casarabe. Recent lidar remote-sensing data and data collected during previous archaeological-reconnaissance demonstrate that what now is being identified as the Casarabe culture has a highly integrated, continuous, and dense settlement system covering more than 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi) with multiple sites and relatively close interconnections.[4] The settlement characteristic of the Casarabe culture is being described as low-density urbanism that developed between 500 CE and 1400 CE.[5]

Historically, archaeologists and geographers held that large, complex pre-Columbian societies were unable to develop and flourish in the lowland forests of the Amazon basin because of poor soils for agriculture, protein deficiency of inhabitants, lack of domesticated animals, and limited technology. In 2008, that view was challenged following investigation of ruins in the Llanos de Moxos.[6] More recent lidar data has enabled assessments to develop rapidly that could have taken decades using archaeological methods to prove the inaccuracy of the misjudgment. The lidar data reveals construction by the inhabitants that overcame natural deficiencies.

In general, soil fertility in the Llanos decreases from south to north. The soils of the southernmost Llanos benefit from the deposits of sediments by rivers flowing down from the nearby Andes. The quantities of those sediments decrease northward and the typical infertile lateritic soils of the Amazon prevail.[7] Associated with pre-historic settlements is Amazonian dark earth, called "terra mulata" or terra preta. These highly-productive soils are the product of human occupation and endeavors to improve soil fertility.[8] The people of the Moxos plains domesticated their landscape by practicing raised bed agriculture and improving soils by the addition of organic matter.[9]

Earthworks

editDisagreements about the anthropogenic origin of many of the earthworks in the Llanos de Moxos continue. Likewise, authorities disagree on the number and social complexity of the people who constructed the earthworks, some postulating a large population, others a small population that built the earthworks over a long period of time. Stonework, characteristic of the highland civilization west of the Llanos, was not a feature because there was no surface stone in the area.[10]

Mounds (lomas in Spanish) are scattered throughout the Llanos de Moxos. The total number of mounds is estimated at 20,000. Two to three hundred of these are large mounds rising from 3 metres (9.8 ft) to 5.5 metres (18 ft) above their bases and with a land area of 2 hectares (4.9 acres) to 11 hectares (27 acres). Mounds are concentrated in several areas, suggesting that several regional polities existed, each with its residential and ceremonial centers. The purpose of the small mounds, less than 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, was residential and agricultural.[11]

Agricultural fields demonstrate that farming on the Llanos de Moxos was mostly on long narrow strips of land raised by humans up to 1 metre (3.3 ft) above floodwater levels. The remains of strips, called "camellónes" in Spanish, are as long as 600 metres (2,000 ft) and 20 metres (66 ft) wide. The raised fields permitted drainage during the rainy season.[12] Raised fields may have covered as much as 1,000,000 hectares (2,500,000 acres) of land in the Moxos Plains.[13] Maize and cassava (Yuka) were probably the principal crops.[14]

Forest islands rise above the surrounding swamps. Many are constructed artificially, the products of abandoned monumental mounds and human settlements. Forest islands were used for home sites, agriculture, hunting, and harvesting of wild plant products.[15]

Canals and causeways often connected areas of human settlement, radiating outward from the large mounds. They served multiple functions: transportation, drainage, boundary markers, and enhancing fishery resources.[16] Zigzag causeways in some areas are interpreted as being fish weirs. Fish were probably the main source of protein for the pre-historic inhabitants.[17]

Ring ditches are found in many areas. Ditches were constructed to encircle areas of human settlement and functioned both for drainage of water in the rainy season and for storage of water during the dry season. They were usually less than 1 metre (3.3 ft) in depth and 3 metres (9.8 ft) to 5 metres (16 ft) in width.[18]

Variations among regions

editFour eco-archaeological regions are identified in the Llanos de Moxos.

Region one: North of the city of Santa Ana del Yacuma and west of the Mamoré River is an area of water-logged and poor soils. Many large raised agricultural fields are the distinctive remains of its prehistoric inhabitants, the raised fields being necessary for drainage and improvement of the soils. Although there was probably a large pre-historic population in this region, there is little evidence of a complex society.[19]

Region two: East of the Mamoré River and centered on the town of Baures and the Baures River is an area of many forested islands, mostly natural, which were inhabited and circled by ditched agricultural fields, ring ditches, fish weirs, and many canals and zigzag causeways. It appears that the earthworks in this area were constructed not long before the Spanish arrived.[20]

Region three: West of the city of Trinidad centered on the town of San Ignacio de Moxos is an area in which soils are relatively fertile and hosting a large number of earthworks, including mounds, man-made forested islands, raised fields and causeways. The proliferation of earthworks and their variety suggest a more complex pre-historic society than those of regions one and two.[21]

Region four: East of the city of Trinidad and centered on the town of Casarabe is the most fertile and the least-waterlogged region of the Llanos. It contains large numbers of monumental mounds and associated agricultural fields and integrated earthworks. This region probably hosted the most complex societies of the pre-historic Llanos de Moxos.[22]

People

editArchaeologists have found indirect evidence of a human presence in the Llanos de Moxos dating to 8000 BCE in shell middens on several forest islands.[23]

Some of the artifacts in the monumental mounds have been radiocarbon dated to as long ago as 800 BCE.[24] The early Spaniards found six principal ethnic groups in the Llanos: the Moxo (or Mojo), Movima, Canichana, Cayuvava, Itonama, and Bauré. The names of 26 other groups are known. The Baure were considered by the Spanish to be the most "civilized", followed by the Moxo. The other groups lived in smaller communities and on less favored lands. The Canichana or Canisiana were warlike hunters who occupied prime riverfront property on the Mamoré River.[25]

The Llanos were a patchwork of unrelated languages. The Baure and Moxo spoke Arawak languages. Linguists believe that the Arawakan peoples originated further north in the central Amazon basin and migrated to the Llanos, bringing their cassava-based agriculture with them. Most of the other ethnic groups were probably earlier inhabitants of the Llanos than the Arawak-speakers, although the distinct hunting and warrior culture of the Canichana suggests they may have only recently migrated into the Llanos at the time of first contact with the Spanish Empire.[26]

Archaeologist Clark Erickson summarized the early Spanish description of Baure villages:

the villages were large by Amazonian standards and were laid out in formal plans which included streets, spacious public plazas, rings of houses, and large central bebederos (communal men's houses). According to the Jesuits, many of these villages were defended through the construction of deep circular moats and wooden palisades enclosing the settlements. Settlements were connected by causeways and canals that enabled year round travel.

— [27]

Early Spanish explorers in 1617 reported Llanos villages with up to 400 houses. Modern scholars have calculated that such a village would have a population of about 2000 people.[28]

Denevan estimated the pre-Columbian population of the Llanos de Moxos at 350,000 and a population of 100,000 in 1690 when Jesuit priests first established missions in the Llanos. David Block, to the contrary, estimated only about 30,000 inhabitants of the Llanos in 1679. Whichever is more correct, the pre-Columbian population had declined due to the introduction of European diseases, the impact of conquest, and Spanish and Portuguese slave raids. In 1720, the Jesuits in the Llanos counted approximately 30,000 residents in their missions. The population of the Llanos remained fairly stable after that until the nineteenth century.[29]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Prümers, Heiko; Betancourt, Carla Jaimes; Iriarte, José; Robinson, Mark; Schaich, Martin (2022-05-25). "Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon". Nature. 606 (7913): 325–328. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04780-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9177426. PMID 35614221.

- ^ Walker, John H. (2008a) "The Llanos de Moxos" in Handbook of South American Archaeology, ed. by Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell, New York, Springer, p. 927; Block, David (1994), Mission Culture on the Upper Amazon, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. 11

- ^ "Central South America: Northern Bolivia" World Wildlife Fund, http://worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0702, accessed 12 Nov 2016

- ^ Prümers, Heiko; Betancourt, Carla Jaimes; Iriarte, José; Robinson, Mark; Schaich, Martin (25 May 2022). "Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon". Nature. 606 (7913): 325–328. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04780-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9177426. PMID 35614221. S2CID 249065661.

- ^ Watson, Clare (25 May 2022). "Forgotten Ruins of 'Monumental' Amazonian Settlements Discovered in Bolivian Jungle". ScienceAlert.

- ^ Erickson, Clark L. (2008), "Amazonia: The Historical Ecology of a Domesticated Landscape" in Handbook of South American Archaeology edited by Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell, New York: Springer, pp 157-158

- ^ Lombardo, Umberto; Canal-Beeby, Elisa; and Norwich, Heinz Velt, (2011), "Eco-archaeological regions in the Bolivian Amazon," Geographica Helvetica, Vol. 66, No. 3, p. 179

- ^ Walker, John H. (2011), "Amazonian Dark Earth and Ring Ditches in the Central Llanos de Mojos, Bolivia," Culture, Agriculture, Food, and Environment, Vol 33, No 1, pp 2.

- ^ Erickson, pp 157-158

- ^ Erickson, Clark L. (2000), "Lomas de ocupacion en los Llanos de Moxos," Arqueologia de las Tierras Bajas edited by Alicia Duran Coirolo and Roberto Bracco Boksar, Montevideo, Uruguay: Comision Nacional de Arqueologia, pp. 207-226; http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~cerickso/fishweir/articles/Lomas.pdf, English version: http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~cerickso/fishweir/articles/EricksonLomasMoxos2000.pdf, both accessed 27 April 2021

- ^ Erickson, (2000), pp. 207-226

- ^ "Prehispanic Raised Field Agriculture: Applied Archaeology in the Bolivian Amazon," http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cerickso/applied3.html, accessed 14 Nov 2016

- ^ Renard, D., Iriarte, J., Birk, J.J., Rostain, S., Glaser, B. and McKey, D. (2012), "Ecological engineers ahead of their time: The functioning of pre-Columbian raised-field agriculture and its potential contributions to sustainability today", Ecological Engineering, Vol 45, No. p. 31

- ^ "Prehispanic Raised Field Agriculture". www.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 14 Nov 2016.

- ^ Erickson (2008), p. 169

- ^ Erickson, 2008, pp. 173-174

- ^ Walker (2008a), p. 930, Erickson (2008), p. 174

- ^ Walker, John H. (2008b), "Pre-Columbian Ring Ditches along the Yacuma and Rapulo Rivers, Beni, Bolivia: A Preliminary View", Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 421-422. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ^ Lombardo et al, p. 177; Walker, 2008a pp. 929-930

- ^ Lombardo, et al, pp. 177-178; Walker, 2008a, pp. 929-930

- ^ Lombardo, et al, pp. 177-178; Walker, 2008a, pp. 929-930

- ^ Lombardo, et al, pp. 177-178; Walker, 2008a, pp. 929-930

- ^ Lombardo U, Szabo K, Capriles JM, May J-H, Amelung W, Hutterer R, et al. (2013), "Early and Middle Holocene Hunter-Gatherer Occupations in Western Amazonia: The Hidden Shell Middens". PLoS ONE 8(8): e72746. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072746

- ^ Erickson, 2000.

- ^ Block, pp. 16-18

- ^ Block, pp. 16-18

- ^ Danielsen, Swintha (2007), Baure: An Arawak Language of Bolivia, Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies, Universiteit Leiden, The Netherlands, p. 2

- ^ Denevan, William M. (2014), Estimating Amazonian Indian Numbers in 1492" Journal of Latin American Geography, Vol. 13, No. 2, p. 213. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ^ Block, pp. 19-22