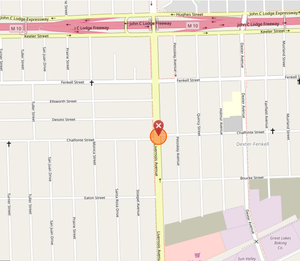

The Livernois–Fenkell riot was a racially motivated riot in the summer of 1975 on Livernois Avenue at Chalfonte Avenue, just south of Fenkell Avenue, in Detroit, Michigan.

Map of the riot location | |

| Date | Friday, August 1, 1975 |

|---|---|

| Location | Livernois Avenue at Chalfonte Avenue, just south of Fenkell Avenue, in Detroit, Michigan |

| Deaths |

|

| Non-fatal injuries | 10 injuries |

The trouble began when Andrew Chinarian, the 39-year-old owner of Bolton's Bar, observed three black youths tampering with his car in the parking lot. He fired a pistol or rifle, fatally wounding 18-year-old Obie Wynn.[2] According to some accounts, Wynn was fleeing; according to others, he was approaching Chinarian with what the latter thought was a weapon, it later emerged that Wynn was holding a screwdriver. He died from a gunshot wound to the back of the head.[3] Crowds gathered and random acts of vandalism, assault, looting and racial fighting along Livernois and Fenkell avenues ensued. Bottles and rocks were thrown at passing cars.[3]

The second man killed was Marian Pyszko, a 54-year-old dishwasher and a Nazi concentration camp survivor who had emigrated from Poland in 1958.[4] As he drove home from the bakery/candy factory where he worked, he was pulled from his car by a group of black youths and beaten to death with a piece of concrete.[5][page needed] Ronald Bell Jordan, Raymond Peoples, and Dennis Lindsay were all charged with first-degree murder.[6]

Police were ordered to not use deadly force, so no shots were fired.[5] A crowd of 700 was dispersed by morning. Angry crowds reappeared and violence resumed the following night – a car became a battering ram and a mob ransacked Bolton's Bar.[3]

Detroit mayor Coleman Young defused the disturbance by appearing in person (along with several clergymen) and ordering every black policeman in the city to police the riot.[7][incomplete short citation]

The damage to property in the Livernois-Fenkell area amounted to tens of thousands of dollars. Fifty-three people were arrested, and ten injuries were recorded (including one firefighter and one police officer). [3]

CBS News reported an unverified claim that the bar served white patrons only, and noted the 25% unemployment rate as an aggravating factor.[8]

See also

editBibliography

editNotes

- ^ Streissguth 2009, p. 115.

- ^ Time 1975.

- ^ a b c d Jet Magazine 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Salpukas 1975a, p. 12.

- ^ a b Darden & Thomas 2013.

- ^ Buchanan, Stanford & Kimble 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Salpukas 1975b, p. 37.

- ^ CBS News 1975.

References

- Buchanan, Heather; Stanford, Sharon; Kimble, Teresa (2007). Eyes on Fire: Witnesses to the Detroit Riot of 1967. Aquarius Press. ISBN 9780971821453. - Total pages: 80

- CBS News (July 29, 1975). "CBS Evening News for Tuesday, July 29, 1975". Vanderbilt Television News Archive. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- Darden, Joe T.; Thomas, Richard W. (2013). Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts, and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9781609173524. - Total pages: 325 - Article on book: Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts, and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide

- Jet Magazine (August 14, 1975). "Violence erupts in Detroit". Jet Magazine. XLVIII (21). Johnson Publishing Company: 6–7. OCLC 20729894. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- Salpukas, Agis (July 31, 1975a). "Detroit Authorities Move To Keep Unrest in Check". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Salpukas, Agis (August 1, 1975b). "Symbols of Black Power". The New York Times. New York City. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- Streissguth, Thomas (2009). Hate Crimes. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438119045. - Total pages: 337

- "The Nation: Close to the Brink". Time. August 11, 1975. Retrieved August 4, 2019.