The World Chess Championship has taken various forms over time, including both match and tournament play. While the concept of a world champion of chess had already existed for decades, with several events considered by some to have established the world's foremost player, an event explicitly held to decide a world champion did not take place until 1886. World Championships were initially privately organized matches, with each requiring the consent of the incumbent champion to take place. After 1948, the International Chess Federation (FIDE) began organizing the Championship under its auspices. The championship was fixed to a three-year cycle, with each challenger decided by a Candidates Tournament. In 1993, the short-lived Professional Chess Association (PCA) split from FIDE, and as a result there were two competing World Championship titles between 1993 and 2006.

Key

edit| Date | The year the event took place, further disambiguated as needed |

|---|---|

| † | Event was a tournament, as opposed to a match. |

| ‡ | Event resulted in a draw, with the champion retaining the title. |

| # | Scheduled event did not take place. |

| ✻ | Event began, but was abandoned without any result. |

| Winner | The winner of the event, or the champion otherwise retaining the title. Numerals denote the updated number of event wins or title defences by the champion. |

| Score | The performance of the eventual champion. Segments such as tiebreaks are listed sequentially. Head-to-head tournament results are given in a footnote. |

| Runner-up | The second-place finisher of the event, or the challenger for a match without a winner |

| Ref | References and footnotes corresponding to the event |

Predecessor events (before 1886)

editChess was first introduced to Europe during the 9th century.[1] In the early modern era, following the solidification of the modern rules of chess, the game continued to carry consistent prestige and public interest.[2] While numerous players have been characterized as the game's strongest over the centuries, the idea of an international chess match or tournament did not occur until the 18th century,[3] and did not materialize until the 19th century.[4] While the following events did not have the title of World Champion at stake, they have been recognized either at the time or in retrospect as indicating the world's leading player.

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1834 | London | Louis de La Bourdonnais | 18–74–56½–5½11½–6½7½–4½4–5 | Alexander McDonnell | Casual play | [5] |

| 1843 | Paris | Howard Staunton | 13–8 | Pierre Saint-Amant | First to 11 wins | [6] |

| 1851† | London | Adolf Anderssen | 15–6[a] | Marmaduke Wyvill | Single-elimination tournament with 16 players | [7] |

| 1858 | Paris | Paul Morphy | 8–3 | Adolf Anderssen | First to 7 wins | [8] |

| 1862† | London | Adolf Anderssen | 11½–1½ | Louis Paulsen | Round-robin tournament with 14 players | [9] |

| 1866 | London | Wilhelm Steinitz | 8–6 | Adolf Anderssen | Best of 15 | [10] |

| 1883† | London | Johannes Zukertort | 22–4 | Wilhelm Steinitz | Double round-robin tournament with 14 players | [11] |

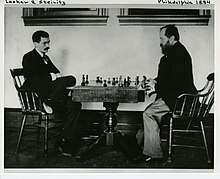

Privately organized matches (1886–1946)

editWith both Wilhelm Steinitz and Johannes Zukertort seen as plausible claimants, the two played a match for the first World Championship in 1886. While Steinitz would later claim that he had been the World Champion since the 1860s, no match before 1886 was played for any formal title.[12] From then until after World War II, championship matches were privately organized, and the champion was not formally obliged to face an opponent. An agreement had to be reached between the champion, the challenger, and the patrons sponsoring each match, which included providing the funds for the prize pool.[13] Lasker's 27-year reign as World Champion is the longest in the history of organized chess since 1886, but featured two separate 10-year spans during which he did not defend his title.

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1886 |

|

Wilhelm Steinitz | 12½–7½ | Johannes Zukertort | First to 10 wins | [14] |

| 1889 | Havana | Wilhelm Steinitz (2) | 10½–6½ | Mikhail Chigorin | Best of 20, tiebreak if required | [15] |

| 1890–1891 | New York City | Wilhelm Steinitz (3) | 10½–8½ | Isidor Gunsberg | [16] | |

| 1892 | Havana | Wilhelm Steinitz (4) | 10–102½–½ | Mikhail Chigorin | [17] | |

| 1894 |

|

Emanuel Lasker | 12–7 | Wilhelm Steinitz | First to 10 wins | [18] |

| 1896–1897 | Moscow | Emanuel Lasker (2) | 12½–4½ | Wilhelm Steinitz | [19] | |

| 1907 |

|

Emanuel Lasker (3) | 11½–3½ | Frank Marshall | First to 8 wins | [20] |

| 1908 |

|

Emanuel Lasker (4) | 10½–5½ | Siegbert Tarrasch | [21] | |

| Jan–Feb 1910‡ | Emanuel Lasker (5) | 5–5 | Carl Schlechter | Best of 10 | [22] | |

| Nov–Dec 1910 | Berlin | Emanuel Lasker (6) | 9½–1½ | Dawid Janowski | First to 8 wins | [23] |

| 1921 | Havana | José Raúl Capablanca | 9–5 | Emanuel Lasker | Best of 24 | [24] |

| 1927 | Buenos Aires | Alexander Alekhine | 18½–15½ | José Raúl Capablanca | First to 6 wins | [25] |

| 1929 |

|

Alexander Alekhine (2) | 15½–9½ | Efim Bogoljubow | First to both 6 wins and 15 points | [26] |

| 1934 | 12 cities[A] | Alexander Alekhine (3) | 15½–10½ | Efim Bogoljubow | [27] | |

| 1935 | 12 cities[B] | Max Euwe | 15½–14½ | Alexander Alekhine | [28] | |

| 1937 | 9 cities[C] | Alexander Alekhine (4) | 15½–9½ | Max Euwe | [29] | |

| Title vacant from 1946 to 1948, following the death of Alekhine. | ||||||

FIDE World Championships (1948–1990)

editIn 1946, Alexander Alekhine died while still holding the title of World Chess Champion. The International Chess Federation (FIDE), which had been founded in 1924, had been attempting to directly participate in organizing the World Championship since at least 1935. By the late 1940s, around half of the plausible contenders for the World Championship were Soviet citizens, and in 1947, the Soviet Chess Federation joined FIDE after decades of declining to do so. FIDE based the 1948 World Chess Championship on the 1938 AVRO tournament that had been organized in part to select a challenger for Alekhine. The tournament ultimately featured five players, three of them Soviet citizens—including the winner, Mikhail Botvinnik. Botvinnik went on to win or retain in four further championship matches. At the same time, FIDE established the rules for the championship going forward. It was organized around a 3-year cycle, during which a series of Zonal and Interzonal tournaments were held, with their highest-scoring performers invited to a Candidates Tournament. The winner of the Candidates tournament in turn played the champion in a match for the title. A defeated champion was entitled to a rematch the following year, after which the 3-year cycle would resume. Botvinnik benefited from this rule twice, in 1958 and 1961.[30]

With the exception of the American Bobby Fischer in 1972, Soviet citizens won every championship from 1948 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. With the further exception of Viktor Korchnoi, who had defected from the USSR in 1976, each challenger was also a Soviet citizen. Following his victory, Fischer never played another game organized by FIDE. Disagreements between the two parties—which included Fischer's insistence on a format that required the victor to get a certain number of wins, as opposed to the number of games in a match being fixed—led to his forfeiting the title in 1975. In the absence of a match, FIDE declared Anatoly Karpov, winner of the 1974 Candidates Tournament, to be the World Chess Champion by default.[31]

While the issue had played a role in Fischer's forfeit, FIDE ultimately did change the match format going forward, such that the first to win 6 games would be champion.[32] Under these rules, Karpov twice defended his title against Korchnoi. The next match—which began in September 1984 and featured the 21-year-old Garry Kasparov as Karpov's challenger—ultimately saw 48 games played over the span of five months, with neither player able to get to 6 wins. In an unprecedented step, FIDE president Florencio Campomanes stepped in and declared the match to have ended with no result. A new match, reverted to having a set number of games, was to be played later in 1985. After nearly being knocked out early in 1984, Kasparov defeated Karpov in their rematch. Over the following decade, the two played three more championship matches, with Kasparov narrowly retaining the title in each.[33]

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948† | Mikhail Botvinnik | 14–6[a] | Vasily Smyslov | Quintuple round-robin tournament with 5 players | [34] | |

| 1951‡ | Moscow | Mikhail Botvinnik (2) | 12–12 | David Bronstein | Best of 24 | [35] |

| 1954‡ | Mikhail Botvinnik (3) | 12–12 | Vasily Smyslov | [36] | ||

| 1957 | Vasily Smyslov | 12½–9½ | Mikhail Botvinnik | [37] | ||

| 1958 | Mikhail Botvinnik (4) | 12½–10½ | Vasily Smyslov | [37] | ||

| 1960 | Mikhail Tal | 12½–8½ | Mikhail Botvinnik | [38] | ||

| 1961 | Mikhail Botvinnik (5) | 13–8 | Mikhail Tal | [39] | ||

| 1963 | Tigran Petrosian | 12½–9½ | Mikhail Botvinnik | [40] | ||

| 1966 | Tigran Petrosian (2) | 12½–11½ | Boris Spassky | [41] | ||

| 1969 | Boris Spassky | 12½–10½ | Tigran Petrosian | [42] | ||

| 1972 | Reykjavík | Bobby Fischer | 12½–8½ | Boris Spassky | [43] | |

| 1975# | Manila | Anatoly Karpov | — | Bobby Fischer | [44] | |

| 1978 | Baguio | Anatoly Karpov (2) | 16½–15½ | Viktor Korchnoi | First to 6 wins | [45] |

| 1981 | Merano | Anatoly Karpov (3) | 11–7 | Viktor Korchnoi | [46] | |

| 1984–1985✻ | Moscow | Anatoly Karpov | 25–23 | Garry Kasparov | [47] | |

| 1985 | Garry Kasparov | 13–11 | Anatoly Karpov | Best of 24 | [48] | |

| 1986 | Garry Kasparov (2) | 12½–11½ | Anatoly Karpov | [49] | ||

| 1987‡ | Seville | Garry Kasparov (3) | 12–12 | Anatoly Karpov | [50] | |

| 1990 |

|

Garry Kasparov (4) | 12½–11½ | Anatoly Karpov | [51] |

Split title (1993–2006)

editIn 1993, following Nigel Short's victory in the Candidates Tournament, FIDE president Campomanes announced that that year's Championship would take place in Manchester, England. Both Kasparov and Short claimed that FIDE had made this decision without consulting either player, in violation of FIDE's regulations regarding the championship. Kasparov and Short responded by splitting from FIDE and forming the Professional Chess Association (PCA),[52] which organized a World Championship match between the two, played in London later that year. Meanwhile, FIDE stripped Kasparov of his title and organized a championship match between Karpov and Jan Timman, who had finished second and third in the Candidates Tournament.[53] For the 13 years between 1993 and 2006, there were two rival titles. While the PCA itself would fold after only a couple of years, Kasparov would retain what is referred to as "Classical" title, which would be inherited by Vladimir Kramnik upon defeating Kasparov in 2000.[54]

Meanwhile, FIDE once again began experimenting with the championship format. Beginning with the 1998 championship, the system of Zonal, Interzonal, Candidates, and Championship stages was replaced with one single-elimination tournament featuring dozens of players competing for the championship. For the next event in 1999, the incumbent World Champion would not automatically qualify for the finals. Due to this additional change, Karpov—who had won three additional titles during the schism—declined to participate going forward. Each of the four Classical Championships retained a traditional match format.[55]

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | London | Garry Kasparov (5) | 12½–7½ | Nigel Short | Best of 24 | [56] |

| 1995 | New York City | Garry Kasparov (6) | 10½–7½ | Viswanathan Anand | Best of 20 | [57] |

| 2000 | London | Vladimir Kramnik | 8½–6½ | Garry Kasparov | Best of 16 | [58] |

| 2004‡ | Brissago | Vladimir Kramnik (2) | 7–7 | Peter Leko | Best of 14 | [59] |

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Anatoly Karpov (4) | 12½–8½ | Jan Timman | Best of 24 | [60] | |

| 1996 | Elista | Anatoly Karpov (5) | 10½–7½ | Gata Kamsky | Best of 20 | [61] |

| 1998† | Lausanne | Anatoly Karpov (6) | 3–32–0 [a] |

Viswanathan Anand | Single-elimination tournament with 100 players | [62] |

| 1999† | Las Vegas | Alexander Khalifman | 18½–11½ [b] |

Vladimir Akopian | [63] | |

| 2000† | Viswanathan Anand | 14–6 [c] |

Alexei Shirov | [64] | ||

| 2002† | Moscow | Ruslan Ponomariov | 19–9 [d] |

Vasyl Ivanchuk | Single-elimination tournament with 128 players | [65] |

| 2004† | Tripoli | Rustam Kasimdzhanov | 20–10 [e] |

Michael Adams | [66] | |

| 2005† | Potrero de los Funes | Veselin Topalov | 10–4 [f] |

Viswanathan Anand | Double round-robin tournament with 8 players | [67] |

FIDE World Championships (2006–present)

editFollowing a period of negotiation, in 2006 the Classical Champion Vladimir Kramnik played a match against the FIDE Champion Veselin Topalov to reunify the World Championship.[68] Since then, the championship has remained under the auspices of FIDE. The Candidates Tournament returned, and with the exception of the 2007 tournament, FIDE would return to a match format for the World Championship. Instead of the previous system of Zonals and Interzonals to provide candidates, the system was redesigned around the Chess World Cup.[69] Later, means for selecting candidates would variously include the FIDE Grand Prix, the FIDE Grand Swiss Tournament, selection by rating, and wild cards selected by the venue hosting the event.[70]

While shorter matches had taken place at various points, the block of 12 classical games was much shorter than matches had been for much of the 20th century. In the 2018 match, all 12 classical games resulted in draws for the first time in the history of the championship. Following this, the number of games was increased to 14.[71] Citing a lack of motivation and interest in the format, incumbent five-time champion Magnus Carlsen declined to defend his title in 2023.[72] Instead, the match featured the two best performers in the Candidates, with Ding Liren defeating Ian Nepomniachtchi to become the new World Champion. Carlsen later declined his spot in the 2024 Candidates Tournament.[73]

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Elista | Vladimir Kramnik (3) | 6–62½–1½ | Veselin Topalov | Best of 12, tiebreaks if necessary | [74] |

| 2007† | Mexico City | Viswanathan Anand (2) | 9–5 [a] |

Vladimir Kramnik | Double round-robin tournament with 8 players | [75] |

| 2008 | Bonn | Viswanathan Anand (3) | 6½–4½ | Vladimir Kramnik | Best of 12, tiebreaks if necessary | [76] |

| 2010 | Sofia | Viswanathan Anand (4) | 6½–5½ | Veselin Topalov | [77] | |

| 2012 | Moscow | Viswanathan Anand (5) | 6–62½–1½ | Boris Gelfand | [78] | |

| 2013 | Chennai | Magnus Carlsen | 6½–3½ | Viswanathan Anand | [79] | |

| 2014 | Sochi | Magnus Carlsen (2) | 6½–4½ | Viswanathan Anand | [80] | |

| 2016 | New York City | Magnus Carlsen (3) | 6–63–1 | Sergey Karjakin | [81] | |

| 2018 | London | Magnus Carlsen (4) | 6–63–0 | Fabiano Caruana | [82] | |

| 2021 | Dubai | Magnus Carlsen (5) | 7½–3½ | Ian Nepomniachtchi | Best of 14, tiebreaks if necessary | [83] |

| 2023 | Astana | Ding Liren | 7–72½–1½ | Ian Nepomniachtchi | [84] | |

| 2024 | Singapore | Gukesh Dommaraju | 7½–6½ | Ding Liren | [85] |

Unrecognized championship events

editIn 1909, amid discussions that would ultimately culminate with the World Championship match played the following year, Emanuel Lasker played a casual match with Dawid Janowski in Paris. This was reported in later decades as being a World Championship match.[86] However, research by Edward Winter has demonstrated that the title was not at stake.[87]

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Runner-up | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1909 | Paris | Emanuel Lasker | 8–2 | Dawid Janowski | Best of 10, casual play |

See also

edit- Fischer–Spassky (1992 match) – rematch between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky in Belgrade 20 years after their first match, considered by Fischer to be and billed as a World Chess Championship. Fischer won 10–5, with 15 draws.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Murray 1913, p. 405.

- ^ Murray 1913, pp. 774–779.

- ^ Murray 1913, p. 845.

- ^ Murray 1913, p. 883.

- ^

- Pope, Nick. "1834 La Bourdonnais–Macdonnell Matches". Chess Archaeology. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- Capablanca 1977, p. 47

- Sergeant 1934, p. 39, "Labourdonnais by his victory might fairly be entitled to call himself the leading player of the world"

- ^

- Wall, Bill (16 August 2007). "Staunton Beats a Saint". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023.

- Horowitz 1973, p. 3

- Harding 2012, pp. 43–46

- ^

- ^

- Lawson, David (2010). Aiello, Thomas (ed.). Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess. Lafayette: University of Louisiana Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-887366-97-7.

- Horowitz 1973, pp. 5–6, 15–16

- ^ Horowitz 1973, p. 16; Löwenthal, Johann (1864). The Chess Congress of 1862. H. G. Bohn. OCLC 651260808.

- ^

- Capablanca 1977, p. 47

- Murray 1913, p. 888, "But after 1860 the opinion that the Tournament was not the best way of discovering the strongest player of the day became general, and the match became the recognized test. It was as a result of his match with Wilhelm Steinitz, in 1866, which he lost by 6 games to 8, that Anderssen's supremacy is assumed to have come to an end."

- ^

- Winter 2023a

- "The International Tournament of 1883". Chess Player's Chronicle. 27 June 1883. p. 26.

- ^ Winter 2023a.

- ^ Winter 1954, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Murray 1913, p. 889.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Pope, Nick. "1890 Gunsberg-Steinitz World Championship Match". Chess Archaeology. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 208–211.

- ^ Pope, Nick. "1894 Lasker-Steinitz World Championship Match". Chess Archaeology. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 213.

- ^ "The Championship Match". Free Press Prairie Farmer. 24 April 1907. p. 6. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tarrasch, Siegbert (2021) [1908]. Der Schachwettkampf Lasker-Tarrasch um die Weltmeisterschaft im August-September 1908 [The Lasker–Tarrasch chess competition for the world championship in August–September 1908] (in German). De Gruyter. pp. 9–110. doi:10.1515/9783112515143. ISBN 978-3-11-251514-3. S2CID 244540032.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 216.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 217; Wilson 1975, p. 151.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Verhoeven & Skinner 1998, pp. 364–371.

- ^ Verhoeven & Skinner 1998, pp. 489–491.

- ^ Euwe, Max; Alekhine, Alexander (1973) [1936]. Smith, Ken (ed.). Euwe vs. Alekhine Match 1935. Translated by DeVault, Roy. Dallas, TX: Chess Digest. OCLC 3146006.

- ^ Botvinnik, Mikhail (1973) [1937]. Smith, Ken (ed.). Alekhine vs. Euwe Return Match 1937. Translated by DeVault, Roy. Dallas, TX: Chess Digest. OCLC 4395696.

- ^ Winter, Edward (2004). "Interregnum". chesshistory.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Plisetsky & Voronkov 1994, pp. 363–366.

- ^ Plisetsky & Voronkov 1994, p. 365.

- ^ Winter 1988.

- ^ Horowitz 1973, pp. 120–136; Kažić 1974, p. 224.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 225.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 226.

- ^ a b Kažić 1974, p. 227.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 228.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 229.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 230.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Kažić 1974, p. 231.

- ^ Kažić 1974, pp. 232–241.

- ^ Plisetsky & Voronkov 1994, pp. 361–366.

- ^ Winter 1981, p. 169.

- ^ Calvo, R. (1981). Merano 1981 Karpov–Korchnoi: Lucha por el Campeonato del mundo de ajedrez (in Spanish). San Sebastián: Jaque. ISBN 978-84-300-6139-6.

- ^ Kasparov 2008, pp. 54–254; Winter 1988.

- ^ Kasparov 2008, pp. 277–419.

- ^ Kasparov 2009, pp. 21–237.

- ^ Kasparov 2009, pp. 238–428.

- ^ Kasparov 2010, pp. 81–282.

- ^ "Kasparov Breaks With World Chess Body". The New York Times. 27 February 1993. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "A Chess Title Match Is to Start on Sept. 7". The New York Times. 24 April 1993. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ McClain, Dylan Loeb; Fleck, Fiona (4 October 2004). "And They're Off, but Will Winner Be True Champion of Chess?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ McClain, Dylan Loeb (31 October 2000). "A Chess Match Is Waged for a World Title Whose Authenticity Is Challenged". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Keene, Raymond D. (1993). Kasparov v. Short 1993: The Official Book of the Match. New York: Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-3308-3.

- ^ Keene, Raymond D. (1995). World Chess Championship: Kasparov v. Anand. New York: Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-4231-3.

- ^ Bareev & Levitov 2007, pp. 29–172.

- ^ Bareev & Levitov 2007, pp. 173–300.

- ^ Uhlmann, Wolfgang; Treppner, Gerd, eds. (1993). Schachweltmeisterschaft 1993: Anatoli Karpow–Jan Timman; Garri Kasparow–Nigel Short (in German). Hollfeld: Beyer. ISBN 978-3-89168-042-1.

- ^ Byrne, Robert (12 July 1996). "Draw and Match: Karpov Triumphs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Kohlmeyer, Dagobert (6 January 2018). "20 years ago: Anand and Karpov fight for the World Championship". Chessbase. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Las Vegas 1999". International Chess Federation (FIDE). 28 August 1999. Archived from the original on 25 April 2001. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Byrne, Robert (7 January 2001). "Anand's Devious Strategy Defeats Shirov in a Match". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "WCC 2001 Results". International Chess Federation (FIDE). 23 January 2002. Archived from the original on 6 August 2002. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "WCC 2004 Results". International Chess Federation (FIDE). 13 July 2004. Archived from the original on 12 August 2004. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Gershon, Alik; Nor, Igor (2007). San Luis 2005. Gothenburg: Quality Chess. ISBN 978-91-976005-2-1.

- ^ Bareev & Levitov 2007, pp. 176, 324–327.

- ^ "Levon Aronian wins FIDE World Cup". Chessbase. 18 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^

- "Rules & regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship cycle 2014–2016" (PDF). International Chess Federation (FIDE). 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- "FIDE reforms the qualifications paths to the Candidates Tournament" (Press release). International Chess Federation (FIDE). 7 January 2023. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Doggers, Peter (26 April 2019). "2020 World Chess Championship: 14 Games, Double The Prize Fund". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Mather, Victor (20 July 2022). "Lacking Motivation, Magnus Carlsen Will Give Up World Chess Title". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Svensen, Tarjei J. (2 May 2023). "Carlsen On Lack Of Motivation, Classical Chess, New WC Formats & Family Life". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Bareev & Levitov 2007, pp. 301–398.

- ^ "Mexico 2007: Vishy Anand is world champion!". Chessbase. 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ McClain, Dylan Loeb (29 October 2008). "Anand Retains World Championship". Gambit Blog. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Ris, Robert (28 April 2023). "Anand beats Topalov in the final game of their 2010 match". Chessbase. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (30 May 2012). "Anand remains king of world chess as Gelfand's time runs out". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Kasparov, Garry (25 November 2013). "A New King for a New Era in Chess". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Crowther, Mark (23 November 2014). "Carlsen retains World Chess Championship title after beating Anand in Game 11". The Week in Chess. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Graham, Bryan Armen (1 December 2016). "Magnus Carlsen retains world chess title after quickfire tie-breaker". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Pereira, Antonio (29 November 2018). "Magnus Carlsen keeps the crown". Chessbase. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Doggers, Peter (11 December 2021). "Magnus Carlsen Wins 2021 World Chess Championship". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Colodro, Carlos Alberto (30 April 2023). "Ding Liren is the new world chess champion!". Chessbase. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ McGourty, Colin (12 December 2024). "18-Year-Old Gukesh Becomes Youngest-Ever Undisputed Chess World Champion". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Horowitz 1973, p. 64; Keene & Goodman 1986, p. 6.

- ^ Winter, Edward (2007). "Chess Notes". chesshistory.com. 5199. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

Works cited

edit- Bareev, Evgeny; Levitov, Ilya (2007). From London to Elista. Alkmaar: New in Chess. ISBN 978-90-5691-219-2.

- Capablanca, José Raúl; Chernev, Irving (1977) [1921, 1928]. World's Championship Matches, 1921 and 1927. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-23189-1.

- Harding, Tim (2012). Eminent Victorian Chess Players: Ten Biographies. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6568-2.

- Horowitz, Al (1973). The World Chess Championship: A History. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7134-2762-2.

- Kasparov, Garry (2008). Modern Chess Part 2: Kasparov vs. Karpov 1975–1985. Translated by Neat, Kenneth Philip. London: Everyman Chess. ISBN 978-1-85744-433-9.

- ——— (2009). Modern Chess Part 3: Kasparov vs. Karpov 1986–1987. Translated by Neat, Kenneth Philip. London: Everyman Chess. ISBN 978-1-85744-625-8.

- ——— (2010). Modern Chess Part 4: Kasparov vs. Karpov 1988–2009. Translated by Neat, Kenneth Philip. London: Everyman Chess. ISBN 978-1-85744-652-4.

- Kažić, B. M. (1974). International Championship Chess: A Complete Record of FIDE Events. New York: Pitman. ISBN 978-0-273-07078-8.

- Keene, Raymond; Goodman, David (1986). The Centenary Match: Kasparov–Karpov III. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5343-0.

- Murray, H. J. R. (2012) [1913]. A History of Chess (Original reprint ed.). New York: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-63220-293-2.

- Plisetsky, Dmitry; Voronkov, Sergey (1994). Russians versus Fischer. Chess World. ISBN 978-5-900767-01-7.

- Sergeant, Philip W. (1934). A Century of British Chess. Philadelphia: David McKay. OCLC 1835573.

- Verhoeven, Robert G. P.; Skinner, Leonard M. (1998). Alexander Alekhine's Chess Games, 1902–1946. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0117-8.

- Wilson, Fred, ed. (1975). Classical Chess Matches: 1907–1913. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-23145-7.

- Winter, Edward, ed. (1981). World Chess Champions. Oxford: Pergamon. ISBN 978-0-08-024117-3.

- ——— (3 April 2023). "Early Uses of 'World Chess Champion'". chesshistory.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ——— (29 July 2023) [1988]. "The Termination". New in Chess. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024 – via chesshistory.com.

- Winter, William (1954). Kings of Chess: Chess Championships of the Twentieth Century. London: Pitman. ISBN 978-4-87187-828-9.

Further reading

edit- Davidson, Henry A. (1981) [1949]. A Short History of Chess (1st pbk. ed.). New York: McKay. ISBN 978-0-679-14550-9.

- Golombek, Harry (1976). Chess: A History. New York: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-11575-2.

- Winter, Edward (ed.). "World Chess Championship Rules". Retrieved 9 January 2024 – via chesshistory.com.

External links

edit- "World Champions Timeline". FIDE World Championship.