Limerigg is a village in the Falkirk council area of Scotland. It lies on the B825 road between Slamannan and Caldercruix surrounded by extensive woodlands on the northern side and lying next to the Black Loch, which formerly fed the Monkland Canal, and close to the former boundary between Stirlingshire and Lanarkshire.

| Limerigg | |

|---|---|

Looking down Slamannan Road, High Limerigg | |

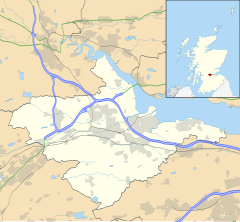

Location within the Falkirk council area | |

| Population | 212 (2001) |

| OS grid reference | NS856708 |

| Civil parish | |

| Council area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | FALKIRK |

| Postcode district | FK1 |

| Dialling code | 01324 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Etymology

editThe name Limerigg or Limerig is a hybrid of Brittonic and Old Norse elements.[1] The first element is either neo-Brittonic *līm, an alleged loanword from Latin līmen, "threshold, lintel", referring to the Stirlingshire border,[1] or *li-m- (> Welsh llif), "a flood, deluge, stream, current", alluding to the nearby Black Loch.[1] The second element is Old Norse hryggr meaning "a ridge" (> Scots rigg).[1]

History and geography

editLimerigg was traditionally a sparsely populated region, with only a few scattered farmsteads forming a community around the isolated area.[2] This changed with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution in Scotland, as like neighbouring villages in the area, great deposits of coal and oil were discovered, and later exploited and extracted.[3] Natural resources brought capitalists and workers into the area, and the population rose rapidly, hitting a high of 1204 by 1881.[4] This expansion was supported by a branch of the Slamannan Railway, which allowed the transfer of Limerigg's natural resources to the Union Canal, and from there, the rest of the central belt. In 1790, the Black Loch was dammed on the south side, which allowed it to be used as a source for both the Monkland Canal and the Forth and Clyde Canal. At least five collieries operated in Limerigg within the second half of the 19th century, with the impact of this resource extraction leaving a long lasting mark on the local area. By the First World War, resource extraction in the area began to become unprofitable as resources began to pile in cheaper from the British Empire, specifically from Australia, and the pits began to close. This caused the miners and much of the local population to leave the area, to elsewhere in Scotland, Britain, or the colonies, in search of employment. The result of this was decline, of both the overall population of the village, and the local quality of life (due to unemployment).

The remaining coal pits closed after the Second World War, which continued the village's overall decline. However, the energetic local councillor and Church of Scotland minister, the Rev Alexander Cameron, used his influence as the local councilor to encourage the Forestry Commission to cover the whole high-moorland area in trees. He was also responsible for demolishing the last of the old miners’ rows and the building of some fifty council houses. As a keen sportsman, he was one of the founders of the first jet-ski club in Scotland, with excellent facilities on the Black Loch, in 1950. His policies helped to slow and stall the overall decline of the village. By the 1970s and 1980s, the decline had begun to set in again, which was attributed to economic downturn and feuds among local families. Intervention from the local MP and the council once again reversed the village's fortunes, and by the late 90s, the village was on the road to recovery, despite initial doubts.[5] In 2010 a 4000-year-old Bronze Age barb and tang flint arrowhead was found on the peat moss on the western outskirts of the village, showing human habitation in the Limerigg area dating as far back as 2000 BC. This is now housed in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. Jet skiing ended on the Black Loch in the early 2000s, with the old jet-ski club being converted into a fishery. Nowadays, Limerigg and the Black Loch is a hotspot for fishing, with the loch being stocked with rainbow trout. The fishery on the loch is private, and a license is required to fish in the loch. This business was forced to temporarily close in the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, alongside many local schools and businesses.[6]

The village is 8.2 miles south of Falkirk, and roughly 1.2 miles south of Slamannan. Limerigg is considered to be within the Parish of Slamannan.

Limerigg is known locally as the Capital of the Braes, a name which came about due to its position as the highest village on the Slamannan Plateau. The Scottish watershed also passes partially through Limerigg.[7]

Education

editLimerigg's educational needs were traditionally served by the local village school, Limerigg Primary School, which was founded in 1878 at the zenith of the village's growth. In 2019, Limerigg Primary School was one of the two schools shut down as a result of a consultation carried out by Falkirk Council. At the time of closure, only five pupils were attending and there were no objections submitted; likely due to the community being just four minutes drive from Slamannan Primary School, with bus services also being provided by the council.[8]

Demography

editThe 2001 United Kingdom Census recorded the population as 212, a fall of roughly 10% since 1991.[9]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d James, Alan. "A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). SPNS – The Brittonic Language in the Old North. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Turner, Louise; Williamson, Claire (2 April 2009) [27 March 2009]. "Limerigg Woods, Falkirk: Archaeological Assessment and Survey. Data Structure Report" (PDF) – via Archaeology Data Service.

- ^ "Museum of the Scottish Shale Oil Industry". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Limerigg from the Gazetteer for Scotland".

- ^ "Crisis in 'the village from hell' Action plan discussed behind closed doors may be too late to save a community".

- ^ "Black Loch Fishery: About Us".

- ^ Wright, Peter (22 July 2013). Ribbon of Wildness: Discovering the Watershed of Scotland. ISBN 9781909912229.

- ^ "No objections as two Falkirk schools mothballed". Falkirk Herald. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019.

- ^ "Insight 2001 Census, No. 3 – 2001 Census population of wards and settlements" (PDF). Falkirk Council. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2009.