Le Griffon (French pronunciation: [lə ɡʁifɔ̃], The Griffin) was a sailing vessel built by French explorer and fur trader René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in the Niagara area of New York in 1679.

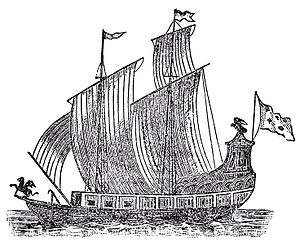

a 17th Century Woodcut/Sketch of Le Griffon

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Le Griffon |

| Builder | French explorer La Salle |

| Launched | 1679 |

| Fate | Disappeared on the return trip of her maiden voyage in 1679 |

| Notes | First full sized sailing ship on the upper Great Lakes[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Barque |

| Tons burthen | 45 tuns |

| Length | 30 to 40 feet (9 to 12 m) |

| Beam | 10-to-15-foot (3 to 5 m) |

| Sail plan | one or two masts; square sails |

| Armament | 7 cannon |

Le Griffon was constructed and launched at or near Cayuga Island on the Niagara River and was armed with seven cannons. The exact size and construction of Le Griffon is not known but many researchers believe she was a 45-ton barque. She was the largest sailing vessel on the Great Lakes up to that time. La Salle and Father Louis Hennepin set out on Le Griffon's maiden voyage on 7 August 1679 with a crew of 32, sailing across Lake Erie, Lake Huron and Lake Michigan through uncharted waters that only canoes had previously explored. The ship landed on an island in northern Lake Michigan adjacent to Green Bay where the local tribes had gathered with animal pelts to trade with the French. La Salle and company disembarked and on 18 September sent the ship back toward Niagara. On its return trip from the island, it vanished with all six crew members and its load of furs.

One consequential result of the effort to build Le Griffin was the discovery of Niagara Falls on the namesake river between lakes Erie and Ontario.

While there have been many theories over the years, there is no clear consensus as to the fate or current location of Le Griffon.

Design

editLe Griffon's pattern closely followed the prevailing type used by explorers to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the New World.[1][2] The exact size and construction of Le Griffon is not known. The widely referenced antique woodcutting of Le Griffon shows her with two masts but many researchers believe she was a 45-ton barque with a single mast with several square sails and 30 to 40 feet (9.1 to 12.2 m) long with a 10-to-15-foot (3.0 to 4.6 m) beam.[1]

Hennepin's first account says she was a vessel of about 45 tons; his second says 60 tons. Because his second account has numerous exaggerations and cases where he credits himself for things that La Salle had done, Hennepin's first account is considered more reliable. In any case, Le Griffon was larger than any other vessel on the lakes at the time, and as far as contemporary reports can confirm, the first named vessel.[citation needed]

She had the figure of a griffin mounted on her jib-boom and an eagle flying above.[1][2] Some say Le Griffon was named for Count Frontenac whose coat of arms was ornamented with the mythical griffin. Hennepin said she was named to protect her from the fire that threatened her.[1]

Historical context

editLe Griffon was the largest fixed-rig sailing vessel on the Great Lakes up to that time.[3] Historian J. B. Mansfield reported that this "excited the deepest emotions of the Indian tribes, then occupying the shores of these inland waters".[1]

La Salle, sought a Northwest Passage to China and Japan to extend France's trade. Creating a fur trade monopoly with the Native Americans would finance his quest and building Le Griffon was an "essential link in the scheme".[2]

The sailing of Le Griffin from the temporary outpost just south of Niagara Falls on the upper Niagara River to Green Bay was part of La Salle's 2nd of four expeditions which ended at the mouth of the Illinois River on the Mississippi. His first expedition in 1669 had aborted somewhere south of Lake Ontario. His third expedition in 1682 retraced the second, then traversed the middle and lower Mississippi River to its mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. His last expedition in 1684 starting from France explored an area on the Gulf coast in eastern Texas where he perished attempting to establish a French colony at the mouth of the Mississippi.

After Le Griffin, it would be more than 80 years before another sailing ship plied the Great Lakes and enabled the commercial exploitation of the lakes and facilitated settlement of the American west.

First ships and preparations

editLe Griffon may or may not be considered the first ship on the Great Lakes, depending on what factors one deems necessary to qualify a vessel for that designation. Decking, permanent masts, and bearing a name are a few of the criteria one might use.[notes 1]

Before 1673, the most common vessel on the lakes was the canoe. While smaller canoes were used on rivers and streams, lake canoes were more commonly larger vessels measuring up to about 35 feet (11 m) long. While some of these were made from a single carved log ("dugout" or "pirogue"), most were bark canoes. Bateaux were also common. They were open vessels (no deck) made of wood measuring up to about 35 feet (11 m) long and capable of carrying three or four tons of cargo. While they were at times fitted with mast and sails, their primary propulsion was either oars or poles. The sails were merely supplemental for traveling down wind. Their inefficiency at beating to windward made them impractical as sailing vessels, and they were not very safe in open water.[citation needed]

Below Niagara Falls: first ships on Lake Ontario

editJames Mansfield[1] says that in the fall of 1678, La Salle built a vessel of about 10 tons burden at Fort Frontenac and that this vessel, named Frontenac, was the first real sailing vessel on the Great Lakes; specifically, on Lake Ontario (which some at the time called Lac de Frontenac). Many authors since Mansfield have followed suit. There is reason, however, to question his assertion.

Justin Windsor notes that Count Frontenac by 1 August 1673, "had already ordered the construction of a vessel on Ontario to be used as an auxiliary force to Fort Frontenac."[4] He also says that at Fort Frontenac in 1676, La Salle "laid the keels of the vessels which he depended on to frighten the English."[4] J. C. Mills [2] quotes a letter from La Salle to the Minister of Marine that says, "The fort at Cataraqui (Fort Frontenac) with the aid of a vessel now building, will command Lake Ontario..."[2] While no date is given for the letter, the location of Mill's reference to it suggests that it was sent before 1677, perhaps as early as 1675. Francis Parkman says that by 1677, "four vessels of 25 to 40 tons had been built for the lake Ontario and the river St. Lawrence."[5] H. W. Beckwith says that in September 1678, La Salle "already had three small vessels on Lake Ontario, which he had made use of in a coasting trade with the Indians."[6] None of these sources ascribe a name to any of these vessels. While the journals of Tonti, Hennepin, and LeClercq (participants with La Salle) do mention a little vessel of 10 tons, none of them apply a name to it.

La Salle's prime focus in 1678 was building Le Griffon. Arriving at Fort Frontenac in late September, he had neither the time for nor the interest in building a vessel at Fort Frontenac to transport building materials, some of which he had recently obtained in France, to a site above Niagara Falls where he could build his new ship. Beckwith's conclusion was that he chose one of his existing vessels, one of about ten tons burden, for sending the first group of men to Niagara.[5] Some of La Salle's associates called this vessel a brigantine; others called it a bark. The accounts agree that this little vessel played a part in the building of Le Griffon.[citation needed]

Le Griffon

editExpedition to upper Niagara

editOn 18 November 1678, after just over a month of preparations at Fort Frontenac, La Salle dispatched Captain La Motte and Father Louis Hennepin together with 15 men and supplies in a vessel of 10 tons. Their mission was to begin selecting a site for the construction of Le Griffon and to erect necessary structures for shelter, storage, and defense. Because the wind was strong from the north, they sailed close to the north shore of the lake, putting in for the nights in various bays along the way. Somewhere near present-day Toronto they were frozen in and had to chop their way out of the ice. From there they struck out across the lake toward the mouth of the Niagara River. They arrived late on 5 December, but the weather was rough and they did not want to run the surf and outflow of the river at night, so they stayed a few miles off shore. On 6 December, they landed safely on the east bank of the river at about where Lewiston, New York is today. They attempted to sail further upstream, but the current was too strong. Ice flowing down the river threatened to damage their little brigantine and after a cable was broken, they hauled the vessel ashore and into a small ravine for protection.[7]

La Salle's men first had to build their lodging and then guard against the Iroquois who were hostile to this invasion of their ancient homeland.[2] La Salle had instructed Hennepin and La Motte to go 75 miles (120 km) into wilderness in knee-deep snow on an embassy to the great village of the Seneca tribe, bringing gifts and promises in order to obtain their good will to build "the big canoe" but many tribal members did not approve.[1][2] Beginning on Christmas Day, 1678, La Motte and Hennepin together with four of their men, went by snowshoe to a prominent Seneca chief who resided at Tagarondies[notes 2] a village about 75 miles (120 km) east of Niagara[notes 3] and about 20 miles (32 km) south of Lake Ontario.[8][page needed] They wished to secure a reliable truce lest the natives interfere with their projects. Negotiations with the Senecas were only moderately successful, so when they left the village they still wondered if the natives would permit them to finish their project. They reached Niagara again on 14 January.[7]

Meanwhile, La Salle and Henri de Tonti, had departed Fort Frontenac in a second vessel some days after La Motte and Hennepin. This was a "great bark" (Hennepin's words) of about 20 tons burden[7] – although Tonti's journal says this was a 40-ton vessel.[9] The vessel carried anchors, chain, guns, cordage, and cable for Le Griffon, as well as supplies and provisions for the anticipated journey. La Salle followed the southern shore of the lake. La Salle decided to visit the Senecas at Tagarondies himself. He put ashore near present-day Rochester, New York, and arrived at Tagarondies very shortly after La Motte and Hennepin had left. He was more successful in securing the Indians' tolerance of his proposed "big canoe" and support buildings. With La Salle back aboard their vessel, the company again sailed west until, about 25 miles (40 km) from Niagara, weather checked their progress.[notes 4][page needed] There was some disagreement between La Salle and the ship's pilot, and La Salle and Tonti went ahead on foot to Niagara. When they arrived there La Motte and Hennepin had not yet returned. While there La Salle selected a site for building Le Griffon.[citation needed] The site La Salle had selected for building Le Griffon has conclusively been identified as at or near the mouth of Cayuga Creek, at Cayuga Island.[5][7][10][page needed]

After La Salle and Tonti left, the pilot and the rest of the crew were to follow with the supply vessel. On 8 January 1679, the pilot and crew decided to spend the night ashore where they could light a fire and sleep in some warmth. It was a calm night and they believed the vessel was securely moored. When a strong wind suddenly arose, they could not make it back to the ship. The vessel dragged its anchor for about nine miles to the east before grounding and breaking up near present-day Thirty Mile Point.[notes 5][page needed] When La Salle heard of the loss (through a messenger or one of the natives), he left Niagara and joined in the salvage effort. They recovered the anchors, chain, and most of the materials critical for Le Griffon, but most of the supplies and provisions were lost. They dragged the materials to the mouth of the Niagara, rested and warmed up a few days in an Indian village, then carried the materials single file through the snow to their settlement above the falls.[citation needed]

Building Le Griffin

editThe keel was laid on 26 January 1679. La Salle offered Hennepin the honor of driving the first spike, but Hennepin deferred to his leader. Having lost needed supplies, La Salle left the building of Le Griffon under Tonti's care, and set out on foot to return to Fort Frontenac. While frozen rivers made traveling easy, finding food was not. He arrived there nearly starved only to find that his detractors had succeeded in stirring up doubt and opposition with his creditors. Addressing his problems long delayed his return to the expedition.[notes 6][page needed]

After La Salle's departure, Tonti refloated the little brigantine, and attempted to use it for more salvage work at the wreck, but the winter weather prevented success. He then charged La Motte with salvage by use of canoes.[7]

Progress on Le Griffon was fraught with problems. Crude tools, green and wet timbers, and the cold winter months caused slow progress in the construction of Le Griffon.[2] Suffering from cold and low on supplies, the men were close to mutiny.

While work continued on Le Griffon in the spring of 1679, as soon as the ice began to break up along the shores of Lake Erie, La Salle sent out men from Fort Frontenac in 15 canoes laden with supplies and merchandise to trade with the Illinois for furs at the trading posts of the upper Huron and Michigan Lakes.[2] The uneasy truce with the Indians was tested by threats and attempts of sabotage and murder. Tonti learned of a plan to burn the ship before it could be launched, so he launched ahead of schedule and Le Griffon entered the waters in early May 1679.[citation needed]

A female Native informant who was of the tribe foiled the plans of hostile Senecas to burn Le Griffon as she grew on her stocks. The unrest of the Seneca and dissatisfied workmen were continually incited by secret agents of merchants and traders who feared La Salle would break their monopoly on the fur trade.[2] When the Seneca again threatened to burn the ship, she was launched earlier than planned in Cayuga Creek channel of the upper Niagara River with ceremony and the roar of her cannons. A party from the Iroquois tribe who witnessed the launching were so impressed by the "large floating fort" that they named the French builders Ot-kon, meaning "penetrating minds", which corresponds to the Seneca word Ot-goh, meaning supernatural beings or spirits.[1] The tumultuous sound of Le Griffon's cannons so amazed the Native Americans that the Frenchmen were able to sleep at ease for the first time in months when they anchored off shore. After Le Griffon was launched, she was rigged with sails and provisioned with seven cannon of which two were brass.[1] The French flag flew above the cabin placed on top of the main deck that was elevated above the hull.[2]

Maiden voyage

editNiagara River to Saginaw Bay

editIn July 1679, La Salle directed 12 men to tow Le Griffon through the rapids of the Niagara River with long lines stretched from the bank. They moored in quiet water off Squaw Island three miles from Lake Erie waiting for favorable northeast winds. La Salle sent Tonti ahead on 22 July 1679 with a few selected men, canoes, and trading goods to secure furs and supplies. Le Griffon set off on 7 August with unfurled sails, a 34-man crew, and a salute from her cannon and musketry.[2] They were navigating Le Griffon through uncharted waters that only canoes had previously explored. They made their way around Long Point, Ontario, constantly sounding as they went through the first moonless, fog-laden night to the sound of breaking waves and guided only by La Salle's knowledge of Galinée's crude, 10-year-old chart. They sailed across the open water of Lake Erie whose shores were forested and "unbroken by the faintest signs of civilization".[1] They reached the mouth of the Detroit River on 10 August 1679 where they were greeted by three columns of smoke signaling the location of Tonti's camp whom they received on board.[2] They entered Lake St. Clair on 12 August, the feast day of Saint Clare of Assisi, and named the lake after her. They again sounded their way through the narrow channel of the St. Clair River to its mouth where they were delayed by contrary winds until 24 August. For the second time, they used a dozen men and ropes to tow Le Griffon over the rapids of the St. Clair River into lower Lake Huron. They made their way north and west to Saginaw Bay on Lake Huron where they were becalmed until noon of 25 August. La Salle took personal command at this point due to evidence that the pilot was negligent.[1][2]

Lake Huron storm

editOn noon of 25 August they started out northwest with a favoring northerly wind. When the wind suddenly veered to the southeast they changed course to avoid Presque Isle. However, the ferocity of the gale forced them to retreat windward and lie-to until morning. By 26 August the violence of the gale caused them to "haul down their topmasts, to lash their yards to the deck, and drift at the mercy of storm. At noon the waves ran so high, and the lake became so rough, as to compel them to stand in for land."[1] Father Hennepin wrote that during the fearful crisis of the storm, La Salle vowed that if God would deliver them, the first chapel erected in Louisiana would be dedicated to the memory of Saint Anthony of Padua, the patron of the sailor. The wind did slightly decrease but they drifted slowly all night, unable to find anchorage or shelter. They were driven northwesterly until the evening of 27 August when under a light southerly breeze they finally rounded Bois Blanc Island and anchored in the calm waters of the natural harbor at East Moran Bay off the settlement of Mission St. Ignace, where there was a settlement of Hurons, Ottawas, and a few Frenchmen.[1]

St. Ignace

editUpon Le Griffon's safe arrival at St. Ignace, the voyagers fired a salute from her deck that the Hurons on shore volleyed three times with their firearms. More than 100 Native American bark canoes gathered around Le Griffon to look at the "big wood canoe".[2] La Salle dressed in a scarlet cloak bordered with lace and a highly plumed cap, laid aside his arms in charge of a sentinel and attended mass with his crew in the chapel of the Ottawas and then made a visit of ceremony with the chiefs.[1][2]

La Salle found some of the 15 men he sent ahead from Fort Frontenac to trade with the Illinois but they had listened to La Salle's enemies who said he would never reach the Straits of Mackinac. La Salle seized two of the deserters and sent Tonti with six men to arrest two more at Sault Ste. Marie.[1][2]

Green Bay

editThe short open-water season of the upper Great Lakes compelled La Salle to depart for Green Bay on 12 September, five days before Tonti's return. They sailed from the Straits of Mackinac to Washington Island[1] located at the entrance of Green Bay. They anchored on the south shore of the island and found it occupied by friendly Pottawatomies and 15 of the fur traders La Salle sent ahead. The traders had collected 12,000 pounds (5,400 kg) of furs in anticipation of the arrival of Le Griffon. La Salle gave instructions for Le Griffon to off-load merchandise for him at Mackinac that would be picked up on the return trip. La Salle stayed behind with four canoes to explore the head of Lake Michigan. Le Griffon rode out a violent storm for four days and then on 18 September, the pilot Luc and five crew sailed under a favorable wind for the Niagara River with a parting salute from a single gun. She carried a cargo of furs valued at from 50,000 to 60,000 francs ($10,000 – $12,000) and the rigging and anchors for another vessel that La Salle intended to build to find passage to the West Indies. La Salle never saw Le Griffon again.[1][2]

The fate of Le Griffon

editThere are three accounts from among La Salle's party regarding the fate of Le Griffon: Father Hennepin's, La Salle's own, and that of Henri Tonti. Hennepin said: "They sailed the 18th of September with a Westerly Wind, and fir'd a Gun to take their leave. Tho' the Wind was favorable, it was never known what course they steer'd nor how they perish'd... the Ship was hardly a league from the Coast, when it was toss'd up by a violent Storm in such a manner, that our Men were never heard of since; and it is suppos'd that the Ship struck upon a Sand, and was there bury'd."[11]

La Salle's account was as follows: "The barque having anchored at the north of the Lac des Illinois, the pilot, against the opinion of some savages who assured him that there was a great storm in the middle of the lake, wanted to continue his voyage without considering that the sheltered location where he was prevented him from knowing the strength of the wind. He was barely a quarter of a league from the shore when the savages saw the barque tossed in a manner so extraordinary that, unable to resist the storm even though all of the sails were lowered, a short time later they lost her from sight, and they believed that she was pushed against the shoals that are near the Isles Huronnes, where she was buried."[12]

The above is based on Abbe Bernou's rendition. La Salle's original letter, which survives, says: "The savages, named Pottawatomies, told me that two days after his departure from the island where I had left him, the 18th of September 1679, this blast of wind of which I have told you being raised, the pilot who was with them moored at the north coast where they were lodged, believing the wind favorable for going to Missilimakinac, as, in effect, it was on the beam, and not feeling the violence of it because of the closeness of the land over which it came, set sail against their advice, they having assured him that there was a great storm out in the lake where the lake appeared completely white; but the pilot ignoring them, replied that his ship had no fear of the wind, set sail, and the wind that was blowing increasing greatly, they noticed that he was obliged to furl all of his sails, with the exception of the two large ones, and that, however, the barque did not do more than traverse towards the islands offshore, bars of large sandbanks which extend more than two leagues offshore."

But in another of La Salle's letters, of which only a fragment survives, continues the narrative, via a Native boy, who was given to La Salle as a slave: "He has seen the pilot of the barque that was lost in the lac des Illinois and one of the sailors, which he described to me with details so particular that I cannot doubt it, who were taken with their four comrades in the river Mississippi, while going up toward the Nadouessiou in bark canoes; that the four others were killed and eaten, this the pilot avoided by detonating one of the grenades that they had stolen from the barque and making them understand that if life were given to him and his comrade, he would destroy with similar ones the villages of the enemies of those who had captured them. These savages brought, the following spring, the Frenchmen to the village of the Missourites, where they went to treat for peace, and the pilot detonated, at their request, a grenade, in the presence of this young Pana who was there at the time. These rogues must have taken the plan, counseled by my enemies, to sink the barque and go by the Mississippi to join du Luth, who was among the Nadouessiou, after having taken the best of the merchandise which were inside to exchange for beaver and to withdraw to the baye du Nord, among the English, if their affairs went badly. This is all the more probable as the man named La Rivière, de Tours, who deserted me to follow du Luth, was in the barque, where I had left him after having recaptured him. They could not have taken this route without having passed the house of the Jesuits of the Bay, who have always acted ignorant of it...".

Tonti merely says[citation needed], "As for the boat, it was never heard from again."

After these, history becomes legend. Charlevoix, the early chronicler of the Jesuits (who was not present at these events), says: "No very authentic tidings were had of it after it left the bay. Some have reported that the Indians no sooner perceived this large vessel sailing over their lakes, than they gave themselves up for lost, unless they could succeed in disgusting the French with this mode of navigating; that the Iroquois in particular, already preparing for a rupture with us, seized this opportunity to spread distrust of us among the Algonquin nations; that they succeeded, especially with the Ottawas, and that a troop of these last, seeing the Griffin at anchor in a bay, ran up under pretext of seeing a thing so novel to them; that, as no one distrusted them, they were allowed to go aboard, where there were only five men, who were massacred by these savages; that the murderers carried off all the cargo of the vessel, and then set it on fire. But how could all these details be known when we are moreover assured that no Ottawa ever mentioned it." Charlevoix does not say who the reporters could have been.

In his biography of La Salle first published in 1869, Parkman, who at that time may have been in possession of unpublished material acquired indirectly via Pierre Margry, wrote in a footnote that became a focus of writers and historians that followed, concerning a letter written by La Salle to the governor of New France in 1683. In the letter "La Salle expresses his belief that his vessel, the ‘Griffin,’ had been destroyed, not by Indians, but by the pilot, who, as he thinks, had been induced to sink her, and then, with some of the crew, attempted to join Du Lhut with their plunder, but were captured by Indians on the Mississippi.” Hennepin and Parkman are the sources of all accounts of La Salle and Le Griffen from that time forward.

There is no conclusive evidence about any of the theories about Le Griffon's loss.[1]

Searches and shipwrecks

editLe Griffon is considered by some to have been the first ship lost on the Great Lakes. It was another vessel used by La Salle and Tonti, however, that was the first loss on 8 January 1679. It dragged anchor and ran aground near Thirty Mile Point on Lake Ontario, where it broke apart. Most sources do not ascribe a name to this vessel, and it was one of several La Salle used for fur trading below Niagara.[citation needed]

Le Griffon is reported to be the "Holy Grail" of Great Lakes shipwreck hunters.[13] A number of sunken old sailing ships have been suggested to be Le Griffon but, except for the ones proven to be other ships, there has been no positive identification. Of 22 claims of finding Le Griffin advanced since the 1800s, all but 2 have been definitively dismissed. One candidate was a wreck at the western end of Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, known since at least 1873, when a lighthouse was constructed at the western end of the island. Another candidate is a debris field adjacent to Poverty Island at the entrance to Green Bay discovered by private maritime company The Great Lakes Exploration Group In 2018.

In 2022, Wayne Lusardi, Michigan state marine archaeologist, stated bluntly, "The Griffon has not been found."[14]

Mississagi Straits claim

editIn 1873, a lighthouse was constructed near the southwest end of Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, manned by a resident keeper. A shipwreck was on the adjacent shore a mile north of the Mississagi lighthouse on Manitoulin Island.[15] In 1887, four skeletons were discovered in a depression behind a boulder, and two more in another nearby limestone cave. They were wrapped in birchbark, and identified as Natives at that time. By coincidence, six was the number of sailors on Le Griffin. Found with the skeletons were a number of metal tokens reportedly with French markings, and a silver watch later dated to the 17th century. The possible remains of Le Griffon were found in 1898 by lighthouse keeper Albert Cullis, on a beach on the western edge of Manitoulin Island in northern Lake Huron. Results of testing some of the artifacts were disputed.[16][17] According to one report the wreck had no centerboard; keel was an oak timber a foot square-it was fastened to two parallel timbers running fore and aft inside the ship. Fastenings were 36 inch iron bolts. At the turn of the bilge the hewed timbers which formed the bottom grooved for grounding keels. Bolts and spikes were crude workmanship cut from square bars and threads formed by forcing a nut into the bar and then finished by hand. The iron was a type smelted by wood as fuel in France during the 1600's. Lead caulking was of a type used in French galiots of the period. A couple of lead cups like the end of a plunger for opening drains [tips of rams for loading cannons{?}]. An old indian told lighthouse keeper William Grant that the wreck had been there during the boyhood of his father in 1780s–1790s. The wreck had always been in the memories of the oldest inhabitants; earliest settlers had salvaged iron from the wreck for harrow teeth and used lead from its seams for bullets and fishing weights. Sometime before 1930 a fisherman whose tug was in Mississagi Straits pulling up his anchor found one fluke broken and the other had timbers of a wreck. In the 1930's a Navy commander and a state archeologist saw the hand hewn timbers of the wreck; all that was left was a section of the bottom 15 by 30 feet remained.[18] A 2021 book concludes that Le Griffin was indeed wrecked at Manitoulin Island[19][20]

The skeletons, and most of the artifacts collected from the two caves and the wreck, long stored in the lighthouse, were lost in a series of very unfortunate accidents. The remains of the wreck on the shore were washed away in a storm in 1942. All that is left today is a few pieces of iron, wood and some lead caulking from the ship.

Other claims

editIn 2001 near Poverty Island, adjacent to Green Bay on Lake Michigan, a 10.5' pole sticking up out of the lakebed was discovered by private marine company Great Lakes Exploration Group, founded by Steve and Kathie Libert. After years of legal squabbles the Michigan Department of Natural Resources issued a permit, and on 16 June 2013, an underwater pit was dug allowing US and French archeologists to examine the object for the first time. They discovered a 15-inch slab of blackened wood that might have been a human-fashioned cultural artifact.[21] On 19 June 2013, teams of archaeologists determined the wood pole whose full length was 19', was not attached to a ship, and retrieved it from the lake. The archaeologists split, some concluding it was likely a bowsprit dating from a ship hundreds of years old, and others that it was a common pound net stake used for fishing nets in the 19th century.[22][23] Later radio carbon dating was inconclusive, indicating it could have been fashioned between 1660 and 1950.[24] During excavation of the pole, another nearby area was searched. Sonar showed an object approximately 40 by 18 feet (12.2 by 5.5 m) (similar to the dimensions of Le Griffon) located under several feet of sediment, but excavation found nothing further. It was later postulated that a shoal of mussels caused a false sonar reading.

In 2018, Great Lakes Exploration group, using satellite and aerial images, located a shipwreck and debris field 3.8 miles from the excavated site. In response to a request to excavate the wreck, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources in an email, has dismissed the Liberts' claim, detailing thus: "Our archeologist's review of recently published media images reveals the remains of a shipwreck that features typical late 19th-century Great Lakes shipbuilding materials and methodologies, and scantlings that are entirely too large to be a French colonial vessel. The keelson structure with mast steps, paired floors and futtocks, and ceiling timbers all suggest a sailing craft, probably a schooner or schooner-barge, that was built and operated during the last half of the 1800s. Additionally, this particular shipwreck is well-known, can be clearly seen on aerial imagery internet sites, and has been visited by state authorities."[25]

The most recent substantive claim to finding Le Griffon was 27 December 2014, when two divers, Kevin Dykstra and Frederick Monroe, announced the discovery of a wreck that they believed was Le Griffon, based on the bowstem, which to some resembles an ornamental griffin.[26][27] Their claim was quickly debunked when Michigan authorities dove down on 9 June 2015 after receiving the coordinates to verify its authenticity. Michigan state maritime archaeologist Wayne R. Lusardi presented evidence that the wreck was, in fact, a tugboat due to its 90-foot (27 m) length and presence of a steam boiler.[28]

See also

edit- La Belle, another similar La Salle sailing ship

Notes

edit- ^ In this article, the word "ship" is used in its broader sense, not in the technical sense of referring to a vessel with three or more masts rigged with square sails.

- ^ About a mile south of present-day Victor, New York, currently preserved as Ganondagan State Historic Site.

- ^ Hennepin's journal says 32 leagues (converts to 96 miles (154 km)), but his figure is an estimate made while snowshoing through the country. The straight-line distance is about 75 miles (121 km).

- ^ Kingsford says it was either contrary wind or they were becalmed. Tonti's journal says it was adverse winds.

- ^ Kingsford's text says Thirty-nine Mile Point, but modern charts do not show that name. Thirty Mile Point is an established location and fits better with the rest of the narrative. That would also put their forward progress on 8 January, at about 20 miles (32 km) from Niagara. It is not clear if the ship had advanced west after the departure of La Salle and Tonti.

- ^ Sources disagree on how long this delay was. Some say La Salle made multiple trips, especially after the spring thaw. Others say he did not return to Niagara until July.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Mansfield, J.B., Ed. (1899). History of the Great Lakes: Volume I. Chicago, Illinois: J.H. Beers & Co. pp. 78–90. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mills, James Cooke (1910). Our Inland Seas: Their Shipping & Commerce for Three Centuries. Chicago, Illinois: A. C. McClurg & Co. pp. 36, 37, 40, 43, 50–56, 59–64, 112, 193. ISBN 9780722201176. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ [1] Harriette Simpson Arnow, Seedtime on the Cumberland, Michigan State University Press. (2013)]

- ^ a b Windsor, Justin (1894). Geographical Discovery in the Interior of North America in its Historical Relations, 1534–1700. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co. pp. 252, 255.

- ^ a b c Parkman, Francis (1879). La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West. Boston: Little Brown & Co. pp. 109, 133, 124.

- ^ Beckwith, Hiram Williams (1881). History of Montgomery County together with Historic Notes on the Wabash Valley. Chicago: H. H. Hillan and N. Iddings. p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e Kingsford, William (1887). The History of Canada – Vol. 1, Canada Under French Rule, 1608–1682. Toronto; London: Roswell & Hutchinson; Trubner & Co. pp. 455, 458.

- ^ Hennepin, Louis; Paltsits, Victor Hugo (1903). Thwaites, Reuben Gold (ed.). A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America. Vol. 1. A. C. McClurg & Company. LCCN 03029306.

- ^ The journeys of Rene Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle – Volume 1. New York: Allerton Book Co. 1905.

- ^ Remington, Cyrus Kingsbury (1891). The Shipyard of the Griffon. Buffalo, N.Y.: Press of J.W. Clement.

- ^ Hennepin, Louis (1699). A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America ... Between New-France and New-Mexico ...; with a Continuation, giving an Account of the attempts of the Sieur de la Salle upon the mines of St. Barbe; the taking of Quebec by the English; with the advantages of a shorter cut to China and Japan; to which are added several new discoveries in North America, not published in the French Edition.

- ^ https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol23/tnm_23_213-238.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Sullivan, Patrick (25 July 2005). "Treasure hunter sues for rights". Traverse City Record-Eagle. Traverse City, Michigan. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ^ "Charlevoix couple offers theory on mysterious 1679 shipwreck". 9 March 2022.

- ^ Boys Life September 1959 pp. 18, 76–77

- ^ The Wreck of the Griffon, Kohl and Forsberg, 2015. Seawolf Publishing Co.

- ^ Ashcroft, Ben. "Le Griffon: The Great Lakes' greatest mystery". The Detroit Free Press.

- ^ Boys Life September 1959 pp. 76–77

- ^ MSRA Newsletter 25

- ^ Wdet Possible resting place of great lakes most iconic Shipwreck

- ^ Flesher, John (15 June 2013). "Divers begin Lake Michigan search for Griffin ship". Yahoo. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Flesher, John (19 June 2013). "Griffin Shipwreck: Wooden Beam Not Attached To Buried Vessel, Researchers Say". Huffington Post. Fairport, Michigan. Associated Press. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Scientists disagree on artifact". Interlochen Public Radio. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "The White Whale for Great Lakes Shipwreck Hunters". 30 May 2017.

- ^ "Doubters abound as Charlevoix couple think they found Great Lakes' oldest shipwreck".

- ^ Didymus, JohnThomas (25 December 2014). "'Le Griffon': Muskegon Divers Claim To Have Found The 'Holy Grail' Of Shipwrecks In Lake Michigan". inquisitr.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (19 January 2015). "Treasure hunters find mysterious shipwreck in Lake Michigan". Livescience.com. cbsnews.com.

- ^ Kloosterman, Stephen (18 June 2016). "Four reasons why the Frankfort-area shipwreck can't be the Griffin". Mlive. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

External links

edit- Allen, Durward L. (1959). "If you are in need of a mystery, here is a historic puzzle: What happened to La Salle's Griffon?". Boys' Life. 49 (9). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Boy Scouts of America: 18, 76–77.

Further reading

edit- Kohl, Cris (2004). Shipwreck Tales of the Great L akes. West Chicago: Seawolf Communications, Inc. ISBN 0-9679976-7-4.

- MacLean, Harrison John (1974). The Fate of the Griffon. Chicago: The Swallow Press, Inc; Sage Books. ISBN 0-8040-0674-1.

- Kohl, Chris (2015). The Wreck of the Griffon. Seawolf Communications. ISBN 978-0-9882-9472-1.

- Libert, Steve (2021). Le Griffon and the Huron Islands – 1679. Mission Point Press. ISBN 978-1-9547-8619-6.