The Late Shang, also known as the Anyang period, is the earliest known literate civilization in China, spanning the reigns of the last nine kings of the Shang dynasty, beginning with Wu Ding in the second half of the 13th century BC and ending with the conquest of the Shang by the Zhou in the mid-11th century BC. The state is known from artifacts recovered from its capital at a site near Anyang now known as Yinxu and other sites across the North China Plain. One of the richest finds was the Tomb of Fu Hao at Yinxu, thought to belong to a consort of Wu Ding mentioned in Shang inscriptions.

Core area and range of sites[1] | |||||||||

| Alternative names | Anyang period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Old Chinese | ||||||||

| Geographical range | North China Plain | ||||||||

| Period | Bronze Age | ||||||||

| Dates | c. 1250 – c. 1046 BC | ||||||||

| Type site | Yinxu | ||||||||

| Preceded by | Xiaoshuangqiao, Huanbei | ||||||||

| Followed by | Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 晚商 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

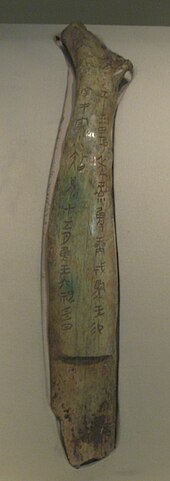

Most Shang writing takes the form of inscriptions on oracle bones used for divinations on behalf of the king. Shang ritual focussed on offerings to ancestors, enabling modern investigators to deduce a king list that largely matches that of the traditional histories of Sima Qian and the Bamboo Annals. The inscriptions also give insight into royal concerns such as weather, the harvest, warfare with neighbouring polities, and mobilizing workers for warfare or agricultural work.

The Late Shang shared many features of the earlier Erlitou and Erligang cultures, including the rammed earth technique for foundations of rectangular walled compounds. Bronze casting reached new heights of decoration and a volume unmatched elsewhere in the world at that time. Workshops in the capital produced ceramics and carved stone and bone for a variety of ceremonial, decorative or utilitarian purposes. Besides writing, new features of the Late Shang included horse-drawn chariots, massive royal tombs and human sacrifice on an unprecedented scale, both in divination rituals and in royal burials.

Discovery

editThe traditional account of early Chinese history is found in the Historical Records (1st century BC) compiled by Sima Qian. In this account, after a series of sage rulers, China was ruled by a succession of dynasties, the Xia, Yin (or Shang), Zhou and Qin, culminating in the Han dynasty of Sima Qian's own time.[3] In the early 20th century, the earlier parts of the textual account were challenged by the Doubting Antiquity School led by Gu Jiegang.[4] At about the same time, archaeological discoveries confirmed the historicity of the last nine Shang kings, and found earlier cities in the Yellow River valley.

Excavations at Anyang

editIn 1898, the scholar Wang Yirong realized that the markings on ancient bones being sold by Chinese pharmacists were an early form of Chinese characters.[7] By 1908, Luo Zhenyu had traced the bones to the village of Xiaotun on the northwest outskirts of Anyang in modern Henan province.[8] The area was quickly recognized as the last capital of the Shang dynasty and named Yinxu 'ruins of Yin' from the name Yīn (殷) used by Sima Qian for the Shang dynasty and by the Bamboo Annals for the dynasty and its last capital.[7] However, the name does not appear in the oracle bones, which refer to the state as Shāng (商), and its ritual centre as Dàyì Shāng (大邑商 'Great Settlement Shang').[9]

In 1928, Dong Zuobin located the pits from which the oracle bones had been dug.[10] The Academia Sinica undertook archaeological excavation of the site until the Japanese invasion in 1937, resuming in 1950.[7] A permanent work station was established on the site in 1959.[11]

The city covered an area of some 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi), focussed on a complex of palaces and temples on a rise surrounded by the Huan River on its north and east, and with an artificial pond on its western side.[12] Further caches of oracle bones were discovered nearby.[13] The area immediately to the south of the palace district contained craft workshops and the residences and cemeteries of the Shang elite.[14] The rest of the city consisted of lineage-based settlements or neighbourhoods, with graves close by residential areas.[15][16] More workshops, handling bronze, pottery, jade and bone, were concentrated in at least three production zones: south of the palace district, east of it across the river, and in the west of the city.[17][18] The Anyang site had no city wall, and a canal or moat around the central district became blocked in the later reigns, suggesting that the Shang felt no danger of invasion.[19]

On the other side of the river, 2.5 km (1.6 mi) to the northwest, a royal cemetery was found on the Xibeigang ridge. Shang kings were buried in large ramped tombs with extensive human and animal sacrifices.[20][21] The royal tombs had been systematically looted, but in 1976 an undisturbed medium-sized tomb was discovered in the southwest part of the palace district.[22] Many of the grave goods recovered were inscribed with the name of Fu Hao, a military leader and consort of Wu Ding known from the oracle bone inscriptions.[23][24] The Tomb of Fu Hao yielded some 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) of bronze vessels, weapons and tools, as well as hundreds of jades and other worked stones, bone carvings and pottery.[25]

In 1999, the remains of a walled city of about 470 ha (1,200 acres) were discovered across the Huan River from the well-explored Yinxu site.[26] The city, now known as Huanbei, contains a palace-temple compound, in which the foundations of two compounds have been excavated.[27] Huanbei was apparently occupied for less than a century and deliberately destroyed by fire around the time of the construction of the Yinxu complex.[28] Chinese archaeologists now assign the city to a Middle Shang period.[29]

Precursors

editEncouraged by the partial confirmation of Sima Qian's account of the Shang, archeologists embarked on a search for earlier capitals. Postwar excavations uncovered earlier urban centres in the area just south of the east–west stretch of the Yellow River.[31] Erlitou, in the valley of the Luo River, flourished in the early part of the 2nd millennium BC.[32] It was succeeded in the middle part of the millennium by the Erligang culture, centred on a large walled city at Zhengzhou and expanding across an area stretching as far south as the Yangtze River.[33] Chinese archaeologists usually identify the Erlitou and Erligang cultures with the Xia and early Shang dynasties respectively, despite the lack of direct evidence.[34]

Around 1300 BC, for reasons that are still unclear, most of the Erligang walled settlements were abandoned and new regional developments from the culture arose.[35] By this time, the sophisticated bronze casting techniques developed by Erlitou and Erligang had spread to, and been further developed by, a string of local cultures along the Yangtze river, from Sanxingdui in the Sichuan basin to Feijiahe near Dongting Lake and Wucheng in the Gan River valley.[36] In the north, intermediate pottery types from before the rise of the Late Shang have been found at sites such as Xiaoshuangqiao and Huanbei.[37]

Several features of Late Shang material culture were already present at Erlitou and further developed during the Erligang period. These include the rammed earth construction technique for walls and foundations, which had been used since the neolithic Longshan culture, and rectangular walled compounds containing pillared halls around a courtyard.[38] Casting of bronze vessels began on a limited scale at Erlitou.[39] During the Erligang period, casters developed a technique of stepwise casting that permitted shapes of arbitrary complexity.[40] Human sacrifice was also practised in the Erlitou and Erligang cultures, though on a much smaller scale than seen at Anyang.[41][42] Other inherited features included the use of jade, the dagger-axe as a standard weapon, burial practices, and pyromancy using tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae.[42][43][44]

The most prominent innovations of the Late Shang – writing, horse-drawn chariots, massive tombs and human sacrifice on an unprecedented scale – all appeared at about the same time, in the reign of king Wu Ding.[45][46] The Shang script is believed to be an indigenous development.[47] In contrast, the sudden appearance of horses and chariots similar in form to those used across the Eurasian steppe, with all the associated technology, is thought to represent an import from the northwest.[48][49] In a band of highlands stretching from the edge of the Tibetan plateau, through the Ordos Plateau and on to the northeast lay a series of cultures that transitioned in the early second millennium BC from an agricultural economy to a mixed agropastoral or fully pastoral economy.[50] These cultures served as an interface between the plains cultures and those of the Eurasian steppe, and had been the vector through which bronze metallurgy reached the North China Plain in the early second millennium BC.[51] Other novel features of the Late Shang include bronze mirrors and animal-headed bronze knives derived from these northern-zone cultures.[52][53]

Writing

editThe earliest attestation of the Chinese language dates from the Late Shang period.[55] The vast majority of surviving Shang texts are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones, with a smaller number of bronze inscriptions and carvings on other materials.[56] Some of the pictographs suggest that the Shang also employed brush writing on bamboo and wooden slips like those known from later periods, but none of these materials have survived.[57]

The oracle bone script consists of an early form of Chinese characters, with each graph representing a word of early Old Chinese.[58] Over 4,000 graphs have been catalogued, though the exact number depends on which are considered graphic variants.[59] A little over 1,200 words have been identified with certainty, but this set includes the core of the Chinese lexicon.[59] A further 1,000 characters consist of identifiable components, but have no agreed interpretation.[59] Most of the unknown characters are thought to represent proper names.[55]

The grammar of the language is broadly similar to that of Western Zhou bronze inscriptions and received texts.[60] As in later forms of Chinese, the basic word order is subject–object–verb, with adjectives and adjectival phrases preceding the nouns they modify.[60] The script provides little information on the sounds of the language, but several cases in which a character is borrowed or modified to write a different word are consistent with current theories on the sounds of Western Zhou Chinese.[61][62]

Chronology

editShang notions of time were based on the rhythms of the agricultural lifestyle, overlain with the ritual schedules they created.[63] Divinations were concerned with the immediate past and present.[64] The longest unit of time used was the lunar month, until the reigns of the last two kings, when ritual cycles roughly a year long were counted.[65] Therefore, modern scholars have had to painstakingly assemble larger-scale Shang chronology from tens of thousands of inscriptions.[66]

Measurement of time

editThe most common terms for parts of the day were based on the motions of the sun or on social events: míng (明 'brightness', i.e. dawn), dàcǎi (大采, around 8 a.m.), xiǎoshí (小食 'small meal'), zhōngrì (中日 'midday'), zè (昃 'afternoon'), dàshí (大食 'large meal'), xiǎocǎi (小采, around 6 p.m.) and zhuó (斲 'cleaving'), the point during the night when the next day began.[67][a] In the inscriptions, these terms are almost always associated with past events, with future events usually discussed in terms of days.[69] There is some evidence that Shang houses had torches to illuminate the night hours.[70]

The Shang named each day with a pair of terms of obscure origin (later known as Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches) representing the position of the day in concurrently running cycles of 10 and 12 days respectively, yielding a 60-day cycle.[72][73] For example, yǐwèi (乙未) was day 2 of the 10-day cycle and day 8 of the 12-day cycle, and thus day 32 of the 60-day cycle.[74] The 60-day cycle seems to have been widely used among elites in northern China during the Late Shang period. Most scholars assume that it continued uninterrupted through the succeeding Western Zhou period up to a solar eclipse recorded in 720 BC, which provides a secure correspondence with Julian days.[75][76][77]

A 10-day period (xún 旬) also functioned as an early Chinese week in expressions such as 'three xún and one day', meaning 31 days.[73][74] (Shang day counts tended to include both the start and end days of an interval.[78]) The incantation xún wáng huò (旬亡禍) '[in the next] ten days [there will be] no disasters' was commonly divined on the last day of each ten-day period.[79] There was no corresponding term for a 12-day period.[80]

Diviners regularly recorded the appearance of a new moon, often assigning it a number. Most scholars believe that the first moon for ritual purposes was the first after the winter solstice.[81] The ritual schedule became increasingly elaborate. By the last two reigns, a full cycle of the five rituals took 36 or 37 xún, approximating the length of a solar year.[82] At around this time, diviners also began to record dates in terms of the number of ritual cycles in the current reign and the current position in the latest cycle.[83]

King list

editThe oracle bones record sacrifices to previous kings and the ancestors of the current king, as in this inscription from the reign of Wu Ding:[84][85]

己未卜禱雨自上甲大乙大丁大甲大庚大戊中丁祖乙祖辛祖丁十示率羝

Crack-making jǐwèi (day 56). Praying for rain to (the ancestors) from Shàng Jiǎ (to) Dà Yǐ, Dà Dīng, Dà Jiǎ, Dà Gēng, Dà Wù, Zhōng Dīng, Zǔ Yǐ, Zǔ Xīn, and Zǔ Dīng, the ten ancestors, (we will) lead-in-sacrifice (?) a ram.— oracle bone Heji 32385[b]

From such evidence, scholars have assembled the implied sequence of kings and their genealogy, finding that it is in substantial agreement with the later accounts, especially for later kings.[87] According to this implied king list, Wu Ding was the twenty-first Shang king.[87]

Ritual records name a deceased Shang king (or royal relative) using one of the day-names of the 10-day Shang week, with a distinguishing prefix.[88] The prefix used depended on the relationship to the current king, with near predecessors denoted by kinship terms such as 兄 Xiōng (elder brother) or 父 Fù (father).[89] The names of more distant predecessors employed prefixes such as 大 Dà (greater), 中 Zhōng (middle), 小 Xiǎo (lesser), 卜 Bǔ (outer), 祖 Zǔ (male ancestor), 武 Wǔ (martial) and a few more obscure names.[88][90] However, the day-name assigned to an individual remained fixed, and that was day on which they most commonly received sacrifice.[91] There is no consensus on how these cyclic names were assigned, but their unbalanced distribution makes it unlikely that they reflect days of birth or death.[92]

Due to the fall of Shang, no such rituals are recorded for the last king, and there is a single record that might refer to the second-last king, so they are conventionally referred to by the names they were given in later accounts, such as the Historical Records.[93] The prefix 帝 Dì (emperor) in these names is thus anachronistic.[94]

| Generation | Older brothers | Main line of descent | Younger brothers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 大乙 Dà Yǐ / 唐 Táng[c] / 成 Chéng | ||||

| 2 | 大丁 Dà Dīng | ||||

| 3 | 大甲 Dà Jiǎ | 卜丙 Bǔ Bǐng | |||

| 4 | 大庚 Dà Gēng | 小甲 Xiǎo Jiǎ | |||

| 5 | 大戊 Dà Wù / 天戊 Tiān Wù | 呂己 Lǚ Jǐ | |||

| 6 | 中丁 Zhōng Dīng | 卜壬 Bǔ Rén | |||

| 7 | 戔甲 Jiān Jiǎ | 祖乙 Zǔ Yǐ | |||

| 8 | 祖辛 Zǔ Xīn | 羌甲 Qiāng Jiǎ[d] | |||

| 9 | 祖丁 Zǔ Dīng / 小丁 Xiǎo Dīng | 南庚 Nán Gēng | |||

| 10 | 象甲 Xiàng Jiǎ | 盤庚 Pán Gēng | 小辛 Xiǎo Xīn | 小乙 Xiǎo Yǐ | |

| 11 | 武丁 Wǔ Dīng | ||||

| 12 | [e] | 祖庚 Zǔ Gēng | 祖甲 Zǔ Jiǎ | ||

| 13 | 廩辛 Lǐn Xīn[f] | 康丁 Gēng Dīng | |||

| 14 | 武乙 Wǔ Yǐ | ||||

| 15 | 文武丁 Wén Wǔ Dīng | ||||

| 16 | 帝乙 Dì Yǐ[g] | ||||

| 17 | 帝辛 Dì Xīn | ||||

The oracle bones also identify six pre-dynastic ancestors: 上甲 Shàng Jiǎ, 報乙 Bào Yǐ, 報丙 Bào Bǐng, 報丁 Bào Dīng, 示壬 Shì Rén and 示癸 Shì Guǐ.[101]

Relative chronology

editUsing ten different criteria, including epigraphy, prose style, diviner names and bone preparation, Dong Zuobin assigned oracle bone inscriptions to five periods I–V corresponding to rulers.[102] Later workers have subdivided some of his periods to refer to the reigns of individual kings.[103] It has also become common to assign pieces to groups of diviners, who were active at different times.[104]

Archaeologists have defined four phases I–IV based on studies of stratigraphy and pottery types at various locations in the Yinxu site.[45] For most of Yinxu I, the site was a small settlement. The first large buildings appeared in the later part of the period, together with oracle bone inscriptions, large-scale human sacrifice and chariot burials.[45] This part of Yinxu I and all of the other three phases can be related to Dong's five inscription periods.[105]

| Anyang team pottery phase |

Dong's inscription periods | Kings' reigns | Major royal diviner groups[h] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Subdivided | ||||

| Yinxu I | |||||

| I | [i] | Wǔ Dīng[j] | Shī 師/Duī 𠂤[k] | ||

| Yinxu II | Bīn 賓 | Lì 歷, type 1 (father Yǐ) | |||

| II | IIa | Zǔ Gēng | Lì 歷, type 2 (father Dīng) | ||

| IIb | Zǔ Jiǎ | Chū 出 | nameless | ||

| Yinxu III | III | IIIa | Lǐn Xīn | Hé 何 | |

| IIIb | Gēng Dīng | ||||

| IV | IVa | Wǔ Yǐ | |||

| IVb | Wén Wǔ Dīng | ||||

| Yinxu IV | V | Va | Dì Yǐ | Huáng 黄 | |

| Vb | Dì Xīn | ||||

The dating information from periods I to IV is too limited to assign inscriptions to a particular year of a king's reign. In contrast, the standardized ritual schedule and recording of cycle counts in period V permits estimates of the lengths of the last two reigns, though these have ranged between 20 and 33 years.[75]

Absolute chronology

editThe earliest securely dated event in Chinese history is the start of the Gonghe Regency in 841 BC, early in the Zhou dynasty, a date first established by the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian. Attempts to establish earlier dates have been plagued by doubts about the origin and transmission of traditional texts and the difficulties in their interpretation. More recent attempts, including by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, have compared the traditional histories with archaeological and astronomical data.[114]

At least 44 dates for the Zhou conquest of the Shang have been proposed, ranging from 1130 BC to 1018 BC.[115] Most recent authors propose dates between 1050 and 1040 BC.[116] David Pankenier, by attempting to identify astronomical events mentioned in Zhou texts, dated the conquest at 1046 BC.[116] The XSZ Project arrived at the same date, based on a combination of the astronomical evidence considered by Pankenier and radiocarbon dating of archaeological layers at Yinxu and proto-Zhou sites.[117][118] Using this date and counting year-long ritual cycles in the last two reigns, the XSZ project assigned accession dates to the last two Shang kings of 1101 BC and 1075 BC.[119]

Oracle bones from the Bīn diviner group (late in Wu Ding's reign and early in that of his successor Zu Geng) mention five lunar eclipses, including the following:[120]

七日己未斲庚申月又食

On the seventh day jǐwèi (day 56) cleaving into gēngshēn (day 57), the moon was eaten.— oracle bone Heji 40610v

Most scholars identify this eclipse with one that astronomers have calculated to have occurred on the evening of 27 December 1192 BC.[121][122] Some of the identifications vary, but most scholars identify these five records with eclipses spanning the period from 1201 to 1180 BC.[121][122][123] This interval implies an approximate end date for Wu Ding's reign. Estimating an average reign length of about 20 years (based on securely dated Zhou rulers), David Keightley proposed a start date around 1200 BC or earlier.[124] Using the statement in the "Against Luxurious Ease" chapter of the Book of Documents that his reign lasted 59 years, the XSZ Project estimated its start date at 1250 BC.[125][l] Ken-ichi Takashima dates the earliest oracle bone inscriptions to around 1230 BC.[130]

Geography

editThe oracle bones describe the Shang world in terms of three concentric regions.[134][135] At the centre was the capital and ritual centre Dàyì Shāng (大邑商 'Great Settlement Shang').[136] Shang control or influence extended to four tǔ (土 'lands') named after the cardinal directions.[137] Many divinations were concerned with harvests or weather in named tǔ, or smaller areas within them.[138] The extent of Shang control, based on shifting alliances and fluctuating military power, is difficult to delineate, and probably varied over time.[139]

The term fāng (方 'sides, regions') was used in a metaphysical sense, to refer to the four directions and associated supernatural powers.[140] It was also used for specific neighbouring groups that might be subordinate polities, allies or enemies, in some cases changing their status over time.[141][142] At least 40 different fāng are mentioned in inscriptions.[143] Shima Kunio attempted to map their positions based on travel time between divinations.[144]

North China Plain

editThe core area of the Late Shang state lay in the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains, stretching from around 200 km (120 mi) north of Anyang to a similar distance to the south.[146][1] In the immediate surroundings of the capital, the Huan River valley experienced a substantial increase in population and growth of regional centres during the Huanbei and Late Shang periods.[147] The Guandimiao site west of Zhengzhou, near the southern end of the core area, is a well-preserved village, which apparently specialized in the production of pottery.[148][149] Many Shang sites have been found in the areas of Hebei the north, especially around the modern city of Shijiazhuang.[150] Taixi (in Gaocheng) seems to have been a strategic outpost near the northern frontier.[151]

In its Upper phase, the Erligang culture had expanded into Shandong, displacing the Yueshi culture. Late Shang material culture expanded further, confining the indigenous Zhenzhumen culture to the eastern part of the Jiaodong peninsula.[152] Large concentrations of settlements occurred along the Ji River, centred on Daxinzhuang, and the adjacent shores of the Bohai, centred on Subutun. These were centres of salt production and harvesting of pearls and shells, as well as mining of copper and lead.[153] Another concentration occurred to the west of the Taishan massif, in the valley of the Si River.[152] These areas also feature aristocratic graves, some of them ramped tombs with human sacrifices like elite tombs at Xibeigang.[154] The site at Subutun features a four-ramped tomb, the only one found outside Anyang, where they were reserved for royal burials. This is interpreted by some archaeologists as indicating a local rival, while others believe the occupant was a favourite of a Shang king.[155]

Another cluster of sites is found in western Shandong and eastern Henan around the Anqiu site, which had been inhabited since the Longshan period.[156] The cemetery at Tianhu, north of the Dabie Mountains, is one of the southernmost sites with Late Shang features.[157] The site also shares features with the many distinct local cultures surrounding it, and may be the lineage cemetery of a local Shang lord.[157][158]

Western highlands

editOf the polities located by Shima Kunio, the most frequently mentioned are to the northwest of Anyang, in the upper Fen River valley and the east bank of the Yellow River to the west.[160] The Qiāng 羌, who are often captured and sacrificed in Shang rituals, are believed to have lived in this area.[161] In Wu Ding's time, the Zhou, possibly at that time residing in the Fen valley, were mentioned as an ally, but in later inscriptions are referred to as Zhōufāng 周方, indicating that they had become more independent or even hostile.[162][163] Several other northwestern allies are mentioned in the Wu Ding period, but disappear from the record in later reigns.[162]

Excavations from the northwestern zone present a mix of cultures.[164] The Jingjie site in the Fen River valley consists of three elite burials with a mix of Shang and Northern Zone artifacts.[165] Many of the bronzes bear an emblem that has been interpreted as Bǐng 丙, a name mentioned as an ally in oracle bones from the reign of Wu Ding.[165][166] The Qiaobei site further down the Fen river also appears to have been allied to the Shang.[167] The Lijiaya culture on the north–south stretch of the Yellow River shows a mix of Shang and Northern Zone features.[168] People of the nearby Ordos Plateau and adjacent areas of the Loess Plateau in western Shanxi had exploited horses since Paleolithic times.[169] This area may have been the source of Shang horses and chariots, perhaps as tribute gifts.[170][171] The name Mǎfāng (馬方 'horse fang') mentioned in the oracle bones may have referred to a polity in this area.[170]

Laoniupo in the Wei valley dominated the route from the Wei valley to the Dan River, which flows into the Han River to the south.[172] The nearby Qinling mountains held extensive copper deposits.[172] The site had been an outpost of the Erligang state, and became a powerful state during the Late Shang period, with close connections to Yinxu.[172] During Yinxu Phase IV, Laoniupo possessed the only known bronze foundry outside of Yinxu producing Shang-style vessels.[172] The site features elite burials similar to those at Yinxu, with many human sacrifices.[173] However, its pottery and other burials show local styles.[173] Laoniupo seems to have become more independent of the Shang core over time, but then declined suddenly, possibly due to the rise of the Zhou, at this time residing further west in the Wei valley, who went on to conquer the Shang.[160][174]

Warfare

editBeyond their central domains, Shang kings maintained their networks of subordinates and allies through a series of military campaigns.[175][176] Campaigns and raids also supplied captives to be sacrificed in Shang rituals.[177]

The bronze foundries at the capital produced a variety of chariot fittings and weapons. The Shang dagger-axe was designed for hand-to-hand fighting on foot.[178] Some 980 bronze arrowheads have been found, compared with 20,400 fashioned from bone.[179] The Shang bow had a range of 60 to 70 m (200 to 230 ft).[180] Some weapons were based on imported designs, such as the máo spearhead, which first appeared at Yinxu in period II and appears to have been developed in the Yangtze region, while daggers with animal-head pommels and some dagger-axes have precursors in Northern zone cultures.[53]

Mobilization

editAlthough the Shang probably had a small standing army, typical campaigns required levies of three or five thousand men, usually provided and led by lineage leaders.[181] Several inscriptions mention troops raised and led by Wu Ding's consort Fu Hao.[182] The most common number of troops was 3,000, who would be organized into right, centre and left units:[183]

丁酉貞: 王作三師右中左

On dīngyǒu (day 34) divined: the king will form three armies, right, centre and left.— oracle bone Heji 33006

Each body of 1,000 footsoldiers would typically be accompanied by 100 archers and 100 chariots.[184] Each chariot carried a driver, an archer and a spearman, all presumably specially trained and drawn from the petty elite class.[185]

The king might lead the army in person, or send one of his generals. Sometimes the Shang would attack together with allies.[186] Divinatory inscriptions concerning planned military campaigns use the verb 'order' (令 líng) for local leaders under the direct control of the king and a different verb 'join with' or '(cause to) follow' for more distant allies.[187][m]

Military history

editInscriptions from the reign of Wu Ding speak of successful major campaigns against the Tǔfāng 土方 and Gōngfāng 工方 west of the Taihang Mountains.[19] Allied states are often mentioned in inscriptions from the Wu Ding period, but not those of later reigns.[189] Under Wu Ding's successor Zu Geng, less successful campaigns against the Shàofāng 召方 and Gōngfāng led to a loss of influence in the west.[19] Limited strikes into enemy territory, often against the Qiāng 羌, are noted in periods III and IV.[19]

By period V (the last two kings), the Shang had established stable control over a smaller area, and no inscriptions refer to outside attacks, or to the loss of troops.[19] Inscriptions of this period also contain fewer references to allied groups.[162] Royal forays were more limited, with the exception of Di Xin's campaign against the Rénfāng 人方 in the Huai River valley to the southeast, which may have lasted at least seven months.[190][191]

Religion

editThe main source of information about Shang religious belief and practice is the oracle bones, supplemented by archaeological finds of ritual vessels and sacrifices.[192] By its nature, this evidence focusses on the concerns of the royal lineage and other elites.[193][n]

Powers

editThe head of the Shang pantheon was Dì 帝, the High God, who commanded the weather and various successes or disasters that might befall the Shang.[195] Many divinations describe seeking Di's approval of or assistance with some endeavour.[196] There are numerous theories regarding the origin of Dì, including an early ancestor, the north celestial pole, or as a generic term for the other powers.[197][198]

The Shang also sought the approval of nature powers such as the Earth Power Tǔ 土, the River Power Hé 河 (the Yellow River) and the Mountain Power Yuè 岳.[199][200][o] Some scholars identify the latter with Mount Song, 220 km (140 mi) to the south of Anyang.[202] Another group, called the "High Ancestors" in the inscriptions and the "Former Lords" in modern scholarship, includes figures such as Kuí 夔 (or Náo 夒) and Wáng-hài 王亥, a name that occurs in some texts from the Warring States period.[199][203] Modern scholars have attempted to identify these with pre-dynastic figures in traditional histories.[203] Another of these figures is Yi Yin, who appears in the traditional histories as a minister of the first Shang king.[204][205]

The ancestors of the king were central to Shang ritual, as a source of power uniquely related to him, and as a reminder of the many generations of kings that had culminated in his rule.[206] Performing the proper sacrifices to each ancestor was a key obligation, and the ancestors were viewed as having influence with Dì and the nature powers.[207] The pre-dynastic ancestors were viewed as the most powerful, able to affect weather and crops.[207][208] All of them were able to affect the king and those around him.[208] Particular significance was attached to kings on the main line of descent to the current king.[209] Royal women were also venerated, particularly consorts of main-line kings and mothers of kings.[209]

Most divinations regarding Dì date from the reign of Wu Ding, after which the ancestors play a greater role.[210] By period V, Dì and the nature powers are hardly mentioned at all.[211] Over the same period, worship of the main-line ancestors became more systematized.[211]

Ritual

editThe ritual centre was a complex of temples and palaces on a hill flanked to the north and south by the Huan River.[212] Archaeologists have mapped the rammed-earth foundations of these buildings, but the density and poor preservation of the foundations makes it difficult to produce a definitive layout.[213][214] It appears that construction and refurbishment continued throughout the Late Shang period.[212] The general consensus is that the northern part of the complex consisted of royal residences, the central part was the main locus of ritual sacrifice, and the southern part consisted of smaller ritual buildings.[215] Inscriptions refer to temples (zōng 宗) of particular ancestors.[213] The glyph used suggests a temple housing a spirit tablet or the altar stand on which it was placed, though no archaeological remains of such tablets have been uncontroversially identified.[216] Inscriptions also mention architectural terms such as táng (堂 'elevated hall'), tíng (庭 'courtyard') and mén (門 'gate').[213]

Many divinations look forward to the coming day, suggesting that Shang ceremonies were performed at sunrise.[217] Usually, the king hosted and offered sacrifices to one of his ancestors or ancestresses on each day, moving through them in sequence.[218] However, when the king was away from the capital, he never divined about sacrifices to ancestors, suggesting that they were thought to remain at the ritual centre.[219]

Sacrificial offerings involved millet ale, grain, and large numbers of animal and human victims.[220] One divination refers to sacrificing 1000 cattle in one ceremony, and several others refer to rituals involving hundreds of animals.[221] The oracle bones refer to at least 14,197 human sacrificial victims, including 7,426 Qiang.[173] The number killed at a time varied from 3 to 300, but was most commonly between 5 and 10.[222] In the temple-palace district, archaeologists have discovered pits containing the skeletons of these victims, many decapitated and otherwise mutilated.[223]

The kings consulted their ancestors and other powers using pyromantic divination, sometimes asking binary questions, but more often seeking approval for a proposed course of action.[224] This involved carefully-prepared animal bones, usually the scapulae of oxen or turtle plastrons, both of which provided convenient flat surfaces.[225] Workers also drilled lines of hollows in the back of each piece.[226] During divination, hot pokers were applied to these hollows, causing cracks in the front surface, which were interpreted as a response.[227] There is no consensus on how cracks were read.[228] The used pieces were then given to scribes, who recorded the charge and the interpretation of the cracks.[229] In some cases, the scribes also later recorded the outcome of the matter divined about.[230] For example,[231][232]

甲申卜殼貞婦好娩嘉王占曰其惟丁娩嘉其惟庚娩引吉三旬又一日甲寅娩不嘉惟女

Crack-making on jiǎshēn (day 21), Que divined: Fu Hao's delivery will be good. The king interpreted: if a dīng day birth, it will be good, if a gēng day, it will be extremely auspicious. On the 31st day, jiǎyín (day 51), she gave birth. It was unlucky, a girl.— oracle bone Heji 14002

Based on an interpretation of certain characters in the oracle bone script, Kwang-chih Chang proposed that Shang kings interceded with the spirit world as shamans.[233][234][235] However, the carefully ordered nature of Shang ritual seems inconsistent with the states of trance or ecstacy that normally characterize shamanism.[234][236]

Burials

editAcross the Huan River lies the Xibeigang cemetery, with eight large tombs each consisting of a square shaft some 12 m (39 ft) deep approached by four ramps dug into the earth and approximately aligned with the cardinal directions.[238][239] These eight tombs, together with an unfinished shaft in their midst, match the nine kings of the Late Shang state, and are generally considered royal tombs.[240] Smaller tombs, two with single ramps (from the south) and three with two ramps (north and south) each, are thought to hold elites of lower status.[240][241] The only other four-ramp tomb of the period, found at Subutun, is variously interpreted as belonging to a favourite of the Shang king or a rival.[155]

Anyang tombs differ from those of Erlitou and Erligang in the introduction of ramps, more elaborate structures, an increase in the number of grave goods, and a greater contrast between the largest tombs and the rest.[242] The effort invested in their tombs shows that the Shang believed that their deceased rulers needed to be provided for in the afterlife, from where they could exert influence over the living.[243] The body of the king was placed in a supine position, oriented north–south, within a wooden chamber constructed at the bottom of the central shaft.[241][244] Under the middle of the coffin, a "waist pit" contained a dog or human sacrificial victim.[245] Rammed-earth ledges surrounding this chamber held the king's attendants who had followed him in death, equipped with weapons or vessels with which to serve the king and often accompanied by dogs.[246][247] The excavated areas were filled with earth and 100 or more beheaded sacrificial victims, mostly young men, buried in a prone position.[246]

The royal tombs have long been looted, but a hint of the treasures they once contained is given by the much smaller tomb of Fu Hao, which was discovered intact just southwest of the temple-palace zone.[248] This medium-sized tomb, with 16 human victims and a dog, also contained 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) of bronze, 755 jades, 110 pieces of worked stone, 564 objects of carved bone, two ivory cups inlaid with turquoise, 6,880 cowrie shells and 11 pots.[25][248] The lower part of the tomb had been damaged by water, so little remained of the occupant and the nested lacquered coffins that excavators believe encased the body.[249]

Tombs in the West Zone of the Yinxu site are believed to have belonged to petty elite lineages.[250] They mirror the pits and ledges of the royal tombs, but at much smaller scale.[250] The grave goods include a few bronze vessels, but more commonly ceramics including ceramic wine-pouring vessels corresponding to the bronze vessels of elite tombs.[243] Many of them were buried with weapons, possibly indicating warriors.[250] Ten graves had a ramp and surrounding graves, which are interpreted as attendants who followed a minor lord in death.[250] Smaller graves with modest goods are found adjacent to lineage settlements across the Yinxu site.[251] Away from the capital, non-elite burials rarely featured grave goods.[252]

Society

editDivination inscriptions refer to various patrilineal lineages (zú 族) or lineage groups, some of which also appear on contemporaneous bronze vessels.[254] Shang society was organized as a socially differentiated hierarchy of such lineage groups, all ultimately bound to the king in various ways.[255][256]

Elites

editThe kingly lineage, centred on the king (wáng 王), occupied the political and ritual pinnacle of Shang society. Some sons also formed their own princely (zi 子) lineages.[255] A cache of oracle bones found at the Huayuanzhang East site, southeast of the palace-temple area, contains divinations performed on behalf of one of these princes during the reign of Wu Ding.[257] Other lineages were more distantly related to the king, forming an extended royal lineage group at the core of the Shang state.[258]

The term fù (婦 'lady') is not completely understood, but is generally thought to denote women of high status, including the king's consorts and those of his sons.[259] Deceased ancestresses received sacrifices under names consisting of Bǐ (妣 'ancestress') and a day name, e.g. Fu Hao was referred to by the posthumous name Bǐ Xīn 妣辛.[260]

The inscriptions mention various titles, for which several interpretations have been proposed. The titles hóu 侯, diàn 甸 and (less commonly) bó 伯 were often appended to place names, suggesting local lords affiliated with the Shang.[261][262] The inscription on the Western Zhou Da Yu ding, dated 58 years after the fall of the Shang, speaks of hóu 侯 and diàn 甸 lords on the periphery of the Shang domain.[263]

Officers

editDivination inscriptions recording numbers of men mobilized, enemies killed or captured, booty taken, animals killed in hunts and quantities of sacrifices must have been supported by a system of record keeping. The organization of armies, the supply of ores and management of bronze-casting imply some level of hierarchical control.[264] The inscriptions mention various kinds of officers in particular roles such as the 'many horses' (Duō Mǎ 多馬), 'many dogs' (Duō Quǎn 多犬), 'many archers' (Duō Shè 多射), 'many artisans' (Duō Gōng 多工) or 'many officers' (Duō Yà 多亞).[265][266] There were also 'junior servitors' (Xiǎo Chén 小臣) responsible for such things as mobilizing workers or cultivation.[267]

However, the Shang government was not yet a bureaucratic structure with clearly-differentiated roles and relationships.[268] Most officials of the Shang state were relatives of the king, by blood or by marriage.[269][270]

Common people

editMany inscriptions refer to mobilizing the population for warfare, opening new land to agriculture and various other tasks.[271] The terms used, rén (人 'people'), zhòng (眾 'multitude') or the combination zhòngrén (人眾), have been much debated, and there is no consensus on whether or how these terms were distinguished by the Shang.[272]

Scholars such as Guo Moruo and Chen Mengjia proposed that the Shang represented the "slave society" phase prescribed by Marxian historical materialism.[273][274] They interpreted such terms as chén (臣 'servitor'), pú (僕 'servant, follower, groom') and yǔ (圉 'prisoners', mostly in period I inscriptions) as denoting slaves.[275] However, there is no mention of people being bought or sold, and no indication that the large numbers of prisoners sacrificed had been used as slave labour.[276][277]

Economy

editThe Late Shang economy was predominantly agricultural.[278] Pottery was produced locally throughout the North China Plain, but specialist crafts were concentrated in the workshops of the capital, drawing on raw materials from the countryside and further afield.[279][280]

Agriculture

editThe staple crop was millet, which had been widely cultivated in northern China since Neolithic times.[281][282] The main varieties were foxtail millet and broomcorn millet.[283] The planting, care and harvesting of the crop was a major concern in divinations.[284] Millet was also fermented to make a drink usually described as "wine", but technically an ale.[220] Hemp was grown and woven for textiles.[285] The Shang also cultivated mulberries and practised sericulture.[286]

Most farming tools were made of wood or stone, including wooden ploughs, shovels of stone, shell or bone, and sickles of shell or stone.[287] A small number of bronze tools have been found, with picks more common than axes.[287] Both animal and human waste were used to fertilize the fields.[288] Although the Shang built a system of drainage ditches around the ritual centre at Xiaotun, there is no evidence of large-scale use of irrigation for agriculture.[289] The inscriptions focus on sufficient rainfall for the crops, while also expressing a fear of flooding.[290]

More than 7% of bone inscriptions were concerned with the weather, with many mentions of winds, rain and thunderstorms.[291] Summers in modern Anyang feature torrential bursts of rainfall, especially in July, triggered when the East Asian Monsoon collides with cold air from the Loess Plateau on the eastern slopes of the Taihang Mountains.[292][293] From late April to early June the region is buffeted by unpredictable and occasionally damaging winds.[294]

During the Late Shang period, summers in the Anyang area were only about 1 °C (1.8 °F) warmer than at present, and might be expected to have had similar weather.[292] In contrast, Late Shang winters were 4–5 °C (7–9 °F) warmer and thus milder and wetter than in modern times.[295] This is confirmed by several inscriptions referring to rain and even thunderstorms in the winter months.[296] It is likely that the growing season was longer in Late Shang times, beginning as early as January or February.[297] Divinations relating to planting are recorded between late December and mid-February, and a few dated appeals to the powers for rain (crucial for newly planted and sprouting crops) occur early in the year.[298] The Yellow River plain to the east and south of Anyang may have received even more rain than the area of the capital.[299]

At that time, most of northern China was covered with deciduous broadleaf forests, in which large animals such as elephants, rhinoceros and tigers roamed.[282] Inscriptions refer to organizing labour to clear lands for farming.[300] Kings often combined their frequent hunts with surveying and clearing new lands to be opened.[282] The connection is reflected in the extension of the noun tián 田 'field' to a verb 'hunt' (take to the field) in inscriptions from period III.[301]

The Shang kept cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs and horses.[302] Many inscriptions describe sacrifices of large numbers of cattle, sheep, pigs and dogs, which were presumably consumed in ritual feasts by the Shang elite.[303] Horses were used to draw chariots for royal hunts and as command vehicles on military expeditions.[304] Many royal burials at Anyang feature sacrificial horses, often together with chariots.[305]

Industries

editAs well as a political and ritual centre, Yinxu was also a centre of craft production.[307] Artisans were clustered in highly specialized production zones in different parts of the site.[18][308] Their lodgings appear to have been of better quality than those of the common people, suggesting a higher status.[309] Some workshops, particularly those producing bronze or worked jade, appear to have been under direct royal control.[310]

Bronze

editThe best-known craft of the Shang was the production of bronze objects.[311] Bronze and the piece-mould process were used from the Erlitou culture, and continued with increasing sophistication and volume of production up to the Late Shang period.[311] The main items produced were ritual vessels, weapons, tools and chariot fittings.[312]

Many types of ritual vessel were produced, the most common being the gū wine goblet and the jué pouring vessel, which were often found paired.[313][314] Next most numerous were various kinds of dǐng cauldron.[315] These vessels were decorated with intricate motifs, requiring extensive labour from a variety of highly skilled artisans.[316][317] Towards the end of the period (Yinxu IV), artisans tended to focus on a smaller number of vessel types and decorative styles.[318] Vessels produced at Yinxu have been found in elite burials within Yinxu and also across the North China Plain and the adjacent regions to the west.[319] Many of these vessels bear brief inscriptions, often just clan insignia.[319] Longer inscriptions tend to come from the Yinxu IV period.[320]

A wide variety of bronze weapons were produced by the Yinxu foundries, many of whose designs were influenced by Yangtze cultures or northern cultures.[321] Elaborately decorated weapons often signified status within Shang society.[322] Some graves featured axes that were too heavy for use in combat and probably awarded as a mark of military command.[322] A small proportion of bronze implements were tools, usually lacking decoration and used for woodworking rather than farming.[323][324] The foundries also produced various fittings for the chariots used by the elite for hunting and as military command vehicles.[46] Handheld bronze bells, 7–21 cm (2.8–8.3 in) in height, have also been found, sometimes in sets of three with matching decoration but random pitch relationship.[325][326]

Six bronze foundries have been found at Yinxu, though they may not all have been operating at the same time.[310][327] One of these, located 700 m (2,300 ft) south of the temple-palace complex, operated throughout the period.[310] The largest centre of bronze production consisted of two foundries 200 m (660 ft) apart in the West Zone of the Yinxu site, which operated in the second half of the period.[310][328]

The volume of bronze production under the Late Shang was many times greater that at Zhengzhou and without parallel elsewhere in the ancient world.[306][329] For example, the mid-sized tomb of Fu Hao contained 1,625 kg (3,583 lb) of bronze objects, and it seems likely that the looted royal tombs originally contained many times as much bronze, exemplified by isolated finds such as the 875 kg (1,929 lb) Houmuwu Ding.[310][329] The sheer volume of production implies considerable mobilization of labour and specialization.[329][330] The huge amount of metals required were obtained from other regions, especially the middle Yangtze, with some from distant northeastern Yunnan.[331]

Ceramics

editLarge amounts of grey-ware pottery, produced from local clays, were used for a variety of purposes at all levels of society.[332][333] Vessel designs and decoration were directly descended from Erlitou and Erligang pottery, with some elements traceable back to the Henan Longshan culture.[334] These vessels were produced across the North China Plain and regions to the west, with variations in each area.[279] The most common type was the lì, a tripod cooking pot.[333]

Shang workshops also produced much smaller amounts of luxury white pottery, richly decorated with motifs similar to those found on bronze and other artifacts.[335][336] The clay from which they were made is found in the Anyang area, but the workshops that produced them have not been identified.[335] The pottery workshops also produced the moulds and crucibles used for casting bronze.[285]

Bone and ivory

editChinese use of worked bone objects peaked in the Late Shang period.[337] Extensive bone working took place both in households and in large specialized workshops.[338] One workshop, in the eastern part of the settlement, has been systematically excavated, with a single trench on the site yielding 34 t (37 short tons) of worked and unworked bones.[339][340]

The most common products were decorative pins, awls and arrowheads.[339][341] More than 20 times more arrowheads of bone have been found than those of bronze.[179] Other items include flat plates, tubes, ocarinas and handles.[342] Many elite tombs feature fine objects carved from the ivory of elephants and boars.[343]

Stone working

editVarious kinds of stone were available from the foothills of the Taihang Mountains just to the west of Anyang.[345] The most common stone products were knives and sickles.[346] A workshop excavated in Xiaotun yielded thousands of slate sickles, some unfinished, suggesting mass production organized by the state.[324][347] Stone axes and shovels were also common.[348]

Many workshops produced finely-carved decorative and ritual objects of marble and jade.[349] A small workshop within the temple-palace complex produced a variety of sculpted jade objects.[349] Sculptures featured human figures and both real and mythical animals.[350] All known examples of marble sculpture were found in royal tombs.[351] Many jade objects were found in the tomb of Fu Hao.[352] Decorated limestone sounding stones have been recovered from several tombs.[345]

Trade

editAs of the 2010s, archaeological investigation of exchange networks was in its infancy, and many details remain unclear.[353] However, it is clear that the capital required a continuous supply of materials of many kinds, some of which may have been exchanged for products of the Yinxu workshops.[354]

The bronze foundries of Yinxu required huge amounts of metal, most of which was sourced from the Yangtze region, with additional sources in Shandong and the Qinling mountains.[355] Most bronzes from phases I and II contain high-radiogenic lead, with the proportion reducing in phase III and then disappearing. This unusual type appears to have originated from northeastern Yunnan.[356] It is also common in bronzes from Sanxingdui in northern Sichuan, and also bronzes from the upper Han River valley from the same period, suggesting that the Late Shang obtained metals from Sanxingdui via the upper Han valley.[357]

Thin stoneware vessels found around Anyang, some glazed, were probably imported from the Yangtze region.[358] Over 30 high-temperature kilns producing nearly identical wares have been found at the Dongtiaoxi site in northern Zhejiang.[359] Similar wares were produced by the Wucheng culture in the Gan River valley.[360] Some evidence suggests experimentation with these techniques at various northern sites to meet the elite demand for these vessels.[359]

Legacy

editAt the time of the reigns of the last two Shang kings, courtyard buildings using Shang techniques and oracle bones inscribed in a distinctive style appeared in the Zhouyuan ('plain of Zhou') region of western Shaanxi.[361] The Zhou conquest of the Shang is marked in the material record by the abrupt appearance throughout the Wei River valley, formerly a materially backward area, of large numbers of bronze vessels, inscriptions, buildings and rich burials, all in Late Shang styles.[362] To legitimate their rule, the Zhou adopted these and other Shang features, including ancestor ritual, divination and the calendar based on the sexagenary cycle.[363][364] However, the Late Shang practice of human sacrifice was simply forgotten.[365] Above all, the Zhou recognized and developed the role of writing for administration and state authority.[363][366]

Relation to traditional accounts

editSima Qian's account of the Shang dynasty is found in chapter 3 of his Historical Records, the "Basic Annals of Yin". This chapter has the form of a list of pre-dynastic ancestors and kings, extended with didactic anecdotes about some kings, but nothing at all about others.[369][370] The bare king list is repeated in the genealogical table in chapter 13.[371]

King lists were maintained by many early states, not only in China but also in the Middle East and the Americas, as a means of legitimizing the current ruler by tracing a linear succession back the founder.[372][p] Sima Qian presented the Shang list as part of a linear sequence of dynasties and rulers stretching from the Yellow Emperor to his own day.[374] Archaeological discoveries have revealed a much more complex picture of the Late Shang period, with other regional powers such as Sanxingdui in the Sichuan Basin and the Wucheng culture on the Gan River.[375] However, the cyclical names of Sima Qian's king list accurately reflect those reconstructed from the ritual schedule, and many of the prefixes also match, especially for later kings.[376]

Sima Qian states that he drew stories from the Classic of Poetry and the Book of Documents.[377] In particular he relied heavily on a collection of prefaces to each of the Documents, which scholars believe was added either late in the Warring States period or early in the Han dynasty.[378][379] Scholars have traced elements to other Warring States texts.[380] Some elements of these anecdotes are clearly mythical.[381] Sima Qian's account, like other early chapters of the Records, is coloured with the values, concepts and governmental structures of the Han period.[382]

Another account of the Shang dynasty is found in the Bamboo Annals, a chronicle of the state of Wei buried in the early 3rd century BC and recovered in the late 3rd century AD, but lost before the Song dynasty. Two versions exist today: an "ancient text" assembled from quotations in other works and a fuller "current text" that many scholars believe to be a forgery.[383] Even the "ancient text" contains elements that must have been added after the work was unearthed.[384]

Both the Records and the Bamboo Annals record several re-locations of the Shang capital. According to the "ancient text" version of the Bamboo Annals, the final move was by Wu Ding's uncle Pan Geng to a place called Yīn (殷).[385] Pan Geng's move to Yin was also described in the Book of Documents chapter "Pan Geng", which is thought to date from the Eastern Zhou period.[386] In contrast, Sima Qian describes Pan Geng as moving to the original Shang capital Bó (亳) south of the Yellow River, followed by a move back north of the river by Wu Yi (or the preceding king Geng Ding according to chapter 13).[387] However, there is no clear evidence for any kings before Wu Ding at the Yinxu site.[388]

Both accounts call the state and its capital Yīn rather than Shāng (商).[389][q] The theory that the dynasty was called Shāng up to Pan Geng's relocation of the capital and Yīn afterwards first appeared in the Diwang shiji by Huangfu Mi (3rd century AD).[391] They also feature later usages not found in the oracle bones, such as calling the rulers 'emperor' (dì 帝) rather than 'king' (wáng 王),[r] and using nián (年) for 'year' rather than sì (祀).[389] Neither account uses the date forms found on the oracle bones.[392] They also do not mention the royal consorts, who feature prominently in the rituals recorded on the oracle bones.[393] Both accounts describe a preceding Xia dynasty, which is not mentioned in Shang inscriptions.[394]

Authors of the received texts seem unaware of the human sacrifice that was central to Shang ritual and is amply attested in archaeological finds. Western Zhou authors reproach the last Shang kings for drunkenness and licentiousness, but do not mention human sacrifice.[395] In contrast, the concept of royal virtue is absent from Shang inscriptions.[396]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Proposed interpretations of the terms involving cǎi (采) include rituals, brightness or the colouring of the sky at dawn and dusk.[68]

- ^ Oracle bones are identified by their number in the Jiaguwen Heji (1978–1982), the most comprehensive catalogue.[86]

- ^ This name is given as 湯 Tāng in the Historical Records and the Bamboo Annals.[96]

- ^ The status of Qiang Jia varies over the history of the oracle bones. During the reigns of Wu Ding and the last two kings, he was not included in the main line of descent, a position also held by the Historical Records, but in the intervening reigns he was included as a direct ancestor.[97]

- ^ The oracle bones (and the Historical Records) include an older brother 祖己 Zǔ Jǐ who did not reign.[98]

- ^ This king is named in the oracle bones of succeeding reigns (as 'brother Xīn', 'father Xīn' and 'grandfather Xīn') and in the Historical Records (as Lǐn Xīn), but not in divinations from the reigns of the last two kings.[99]

- ^ There is a single occurrence of the name 父乙 Fù Yǐ ('father Yǐ') that might refer to this king, but it cannot be securely dated.[100]

- ^ Only the main periods of activity are shown here. The diviner groups often overlapped with adjoining reigns.

- ^ Japanese scholars used the designation Ib for a group of diviners (formerly called the Royal Family Group) that Dong had originally interpreted as a period-IVb revival of Wu Ding-era practices, but are now assigned to period I groups including Shī 師/Duī 𠂤.[109][110]

- ^ Dong also included kings Pan Geng, Xiao Xin and Xiao Yi in his Period I, but no inscriptions can be reliably assigned to pre-Wu Ding reigns.[111][112]

- ^ Authors differ on which of these modern characters should be used in reading the oracle bone glyph.[113]

- ^ This chapter dates from the late Western Zhou or early Springs and Autumns period.[126][127] It propounds a correlation between the virtue of a ruler and the length of his reign, and claims that each of the last six kings ruled for between 3 and 10 years. However, this is quite incompatible with the reign lengths of the last two kings known from the oracle bones, and Pines suggests that the earlier reign lengths in the chapter are no more reliable.[128][129]

- ^ Authors differ on the reading of the character involved.[188]

- ^ Almost all Shang oracle bone inscriptions were found at Yinxu and relate to the Shang elite. The only exceptions are brief inscriptions found at Zhengzhou and Daxinzhuang, totalling 21 and 37 graphs respectively.[194]

- ^ This is the most commonly cited of several interpretations of the glyph for the Mountain Power, which combined the characters 羊 'sheep' and 山 'mountain'.[201]

- ^ Examples include the Sumerian King List, Abydos King List, Hieroglyphic Stairway 1 at Yaxchilan and the Mixtec codices.[373]

- ^ There are two occurrences of the term Shāng in the "ancient text" Bamboo Annals, both in the account the conquest by the Zhou.[390]

- ^ Dì 帝 occasionally appears as a title in the inscriptions, but only attached to direct ancestors of the current king, not all kings.[209]

References

edit- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), p. 351.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 197, Fig. 128.

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 16.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 3.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), p. 344.

- ^ Childs-Johnson (2020), p. 315.

- ^ a b c Jing et al. (2013), p. 345.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 121.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 232.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 120–121.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 123.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), pp. 358–359.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 184.

- ^ Childs-Johnson (2020), p. 359.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), pp. 357–358.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 204.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 356.

- ^ a b Campbell (2014), p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e Keightley (2012), p. 191.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 144, 146–150.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), p. 352.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 136.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 136–137.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 196.

- ^ a b Bagley (1999), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 131.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 291.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), pp. 346, 350.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 132.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 297.

- ^ Bagley (2018), pp. 66–69.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 158–159.

- ^ Bagley (2018), pp. 66–67, 69–70.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 255.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 290–291.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Bagley (2018), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 159–160.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 142, 144.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 159, 167.

- ^ a b Bagley (2018), p. 67.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 158–160.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 174.

- ^ a b c Bagley (1999), p. 181.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 171.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 108.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1988), pp. 206–208.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 202–203.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 297–300.

- ^ Rawson et al. (2020), pp. 136, 138–139.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), p. 360.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 167.

- ^ Chen et al. (2020), pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Boltz (1999), p. 88.

- ^ Qiu (2000), p. 60.

- ^ Qiu (2000), p. 63.

- ^ Boltz (1999), pp. 88, 112.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson (2013), p. 684.

- ^ a b Keightley (1985), p. 65.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 67, 69–70.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 147, 239.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 17.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Keightley (1978), p. 427.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 91.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 20.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Li, Campbell & Hou (2018), p. 1517.

- ^ Takashima (2015), pp. 2–4.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 31.

- ^ a b Smith (2011), p. 1.

- ^ a b Keightley (2000), p. 38.

- ^ a b Keightley (1985), p. 174.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Wilkinson (2013), p. 10.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 32.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 40.

- ^ Smith (2011), p. 9.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Chen et al. (2020), pp. 107–109.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. ix.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 235.

- ^ a b Smith (2011), pp. 3–5.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 95.

- ^ Campbell (2018), p. 210.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 7–9.

- ^ Smith (2011), pp. 3, 5.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 187.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 207.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 185–187, 204–209.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 204, Table 15.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 187, n. f.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 208, n. ad.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 187, 207.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 207, 209.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 185.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 94–133.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 93.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 237, 240–241, 243.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 125.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 203, 204.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 240–241.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1983), p. 8.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 32, n. 18.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 241.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 97–98, 203.

- ^ Li (2002), p. 330.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1983), p. 9, n. 1.

- ^ Lee (2002), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 32.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 248.

- ^ Lee (2002), pp. 31–34.

- ^ Li (2002), pp. 328–330.

- ^ Li (2002), p. 331.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2019), p. 85.

- ^ a b Keightley (1985), p. 174, n. 19.

- ^ a b Zhang (2002), p. 353.

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 31.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 174–175, 228.

- ^ Zhang (2002), p. 352.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 227, n. f.

- ^ Pines (2017), p. 382.

- ^ Pines (2017), p. 363, n. 15.

- ^ Keightley (1978), pp. 427–428, n. 18.

- ^ Takashima (2012), p. 142.

- ^ Tan (1996), pp. 15–18.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 351, 364, 365.

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 130.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 221.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 133–139.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 61.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 61–63.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 110.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 68–72.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 66.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 215–216.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 293.

- ^ Keightley (1983), pp. 537–538.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 220.

- ^ Campbell (2014), pp. 130, 141–142.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 355.

- ^ Li, Campbell & Hou (2018).

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 142.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 361.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 362–363.

- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), p. 363.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 363–366.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 220–222.

- ^ a b Campbell (2014), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 146.

- ^ a b Campbell (2014), p. 152.

- ^ Li (2018), p. 273.

- ^ Li & Hwang (2013), p. 380.

- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), p. 381.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 66–69, 184–187.

- ^ a b c Keightley (2012), p. 192.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 228.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 222.

- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 381, 383.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 223, 225.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 383–384.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 384–385.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 111–113.

- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 386–388.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 229–230.

- ^ a b c d Liu & Chen (2012), p. 379.

- ^ a b c Liu & Chen (2012), p. 380.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 193.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 190–194.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 109.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 184.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 189.

- ^ a b Keightley (2012), p. 11.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1996), p. 164.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 284–285.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 182, 189.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 179.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 285.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 188.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 284.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 120, 132, 162.

- ^ Campbell (2018), p. 132, n. 55.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 180.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 13.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 192–193.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 251–252.

- ^ Eno (2009), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Takashima (2012), pp. 143–146, 155–161.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 252.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 60, 68.

- ^ Eno (2009), pp. 72–77.

- ^ Campbell (2018), p. 151.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 253.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 183.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 104.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 104, n. 21.

- ^ a b Eno (2009), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Eno (2009), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 254.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 255.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 184.

- ^ a b Eno (2009), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Keightley (1999), p. 257.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 261.

- ^ a b Eno (2009), p. 83.

- ^ a b Childs-Johnson (2020), p. 318.

- ^ a b c Thorp (2006), p. 185.

- ^ Childs-Johnson (2020), p. 327.

- ^ Childs-Johnson (2020), pp. 325–338.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 257–258.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 2, n. 1.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 260.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 258.

- ^ Chang (1980), p. 143.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 67.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 187.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 172–173.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 12–14.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 18–21.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. 40.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 2, 40, 41.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 176.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Keightley (1985), fig. 12.

- ^ Chen et al. (2020), pp. 391–393.

- ^ Chang (1994).

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 262.

- ^ Eno (2009), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Eno (2009), p. 93.

- ^ Rawson et al. (2020), p. 137, Fig. 2.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), pp. 205–207.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 147.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 146.

- ^ a b Rawson et al. (2020), p. 141.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 92–96.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 266.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 148.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 267.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 267.

- ^ Rawson et al. (2020), p. 139.

- ^ a b Keightley (1999), p. 264.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Thorp (2006), p. 152.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 208.

- ^ Li, Campbell & Hou (2018), p. 1522.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 269–270.

- ^ a b Jing et al. (2013), p. 351.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Schwartz (2019), pp. 23–70.

- ^ Jing et al. (2013), pp. 351–352.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 294–295.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 245, 276.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 174, 309–310.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 185–186.

- ^ Campbell (2018), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 287.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 111.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 34–38, 94, 119–120, 348–349.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 286–287.

- ^ Li (2013), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 7, n. 30.

- ^ Campbell (2018), p. 153, n. 16.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 281.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 282–284.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Adamski (2022), pp. 12–13, n. 5.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 50, 64–65, 283–284.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 285–286.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 57, 69.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 277.

- ^ a b Campbell (2014), pp. 141–154.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 389–391.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c Sterckx (2018), p. 305.

- ^ Sterckx (2018), p. 304.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 137–161.

- ^ a b Keightley (2012), p. 16.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Keightley (2012), p. 131.

- ^ Sterckx (2018), p. 308.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 168–169, 172.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 169–171.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Keightley (2000), p. 2.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 127.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 3.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 2, 6–7.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Keightley (2000), p. 7.

- ^ Keightley (2000), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Keightley (2012), pp. 161–168.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 136.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 280.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 280–281.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1988), p. 199.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 114.

- ^ a b Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 212.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 357.

- ^ Li (2022), p. 22.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e Liu & Chen (2012), p. 358.

- ^ a b Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 210.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 167–168.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 177.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 195–198.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 201–204.

- ^ Li (2021), pp. 178–181.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 204–208.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 208.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 212–213.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 167–169.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 169.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b Chang (1980), p. 223.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 231.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 209, n. 145.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 214.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 75.

- ^ a b c Bagley (1999), p. 137.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 23.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 358, 360.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 153.

- ^ a b Keightley (2012), p. 15.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 153–155.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 155.

- ^ Li (2021), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 9.

- ^ Shelach-Lavi (2015), pp. 215–216.

- ^ a b Shelach-Lavi (2015), p. 216.

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 138.

- ^ Li (2021), p. 159.

- ^ Li (2021), p. 167.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 157.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 166.

- ^ a b Thorp (2006), p. 159.

- ^ Keightley (2012), p. 13.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 278.

- ^ Li (2021), p. 157.

- ^ a b Keightley (2012), p. 14.

- ^ Li (2021), pp. 169–176.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 159–161.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 161–167.

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 179.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 360, 390.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 358, 363, 379.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), p. 360.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 375–375.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 155, 238–239.

- ^ a b Liu & Chen (2012), p. 362.

- ^ Thorp (2006), p. 239.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 244, 246–248.

- ^ Rawson (1999), p. 385.

- ^ a b Rawson (1999), p. 387.

- ^ Keightley (1999), pp. 290–291.

- ^ Bagley (2018), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 291.

- ^ Thorp (2006), pp. 257, 259.

- ^ Liu & Chen (2012), pp. 371, 372.

- ^ Bagley (2018), p. 81, n.33.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 233.

- ^ Wang (2014), p. 45.

- ^ Wang (2014), p. 21.

- ^ Wang (2014), pp. 21–39.

- ^ Wilkinson (2013), p. 705.

- ^ Bagley (1999), pp. 229–230.

- ^ Keightley (1985), pp. 97, 204–209.

- ^ Nienhauser (1994), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Nienhauser (1994), p. 42, n. 21.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 157–179.

- ^ Keightley (1999), p. 234.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 54.

- ^ Nienhauser (1994), pp. xix–xx.

- ^ Keightley (1978), pp. 422–423.

- ^ Keightley (1978), p. 424, n. 4.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. xiv, n. 6.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 133–134, 150.

- ^ Nienhauser (1994), p. 47, 49, n. 81, 96.

- ^ Campbell (2014), p. 180, n. 6.

- ^ a b Keightley (1978), p. 429.

- ^ Keightley (1978), p. 435.

- ^ Keightley (1985), p. xiv, n. 7.

- ^ Keightley (1978), pp. 429–430.

- ^ Keightley (1978), p. 432.

- ^ Bagley (2018), p. 78.

- ^ Bagley (1999), p. 194.

- ^ Bagley (2018), pp. 78–79.

Works cited

edit- Adamski, Susanne (2022), "Indefinite Terms? Social Groups in Early Ancient China (ca. 1300–771 BC) and 'Strong Asymmetrical Dependency'", in Bischoff, Jeannine; Conermann, Stephan (eds.), Slavery and Other Forms of Strong Asymmetrical Dependencies, De Gruyter, pp. 11–72, doi:10.1515/9783110786989-002, ISBN 978-3-11-078698-9.

- Bagley, Robert (1999), "Shang archaeology", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–231, doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.005, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ——— (2018), "The Bronze Age before the Zhou dynasty", in Goldin, Paul R. (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Early Chinese History, Routledge, pp. 61–83, ISBN 978-1-138-77591-6.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Boltz, William (1999), "Language and Writing", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–123, doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.004, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Campbell, Roderick B. (2014), Archaeology of the Chinese bronze age: from Erlitou to Anyang, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, ISBN 978-1-931745-98-7.

- ——— (2018), Violence, Kinship and the Early Chinese State, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781108178563, ISBN 978-1-107-19761-9.

- Chang, Kwang-chih (1980), Shang Civilization, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02885-7.

- ——— (1994), "Shang Shamans", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), The Power of Culture: Studies in Chinese Cultural History, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, pp. 10–36, ISBN 978-962-201-596-8.

- Chen, Kuang Yu; Song, Zhenhao; Liu, Yuan; Anderson, Matthew (2020), Reading of Shāng Inscriptions, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-6214-3, ISBN 978-981-15-6213-6.

- Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (2020), "Late Shang ritual and residential architecture at Great Settlement Shang, Yinxu in Anyang, Henan", in Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Early China, Oxford University Press, pp. 314–349, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328369.013.16, ISBN 978-0-19-932836-9.

- Eno, Robert (2009), "Shang state religion and the pantheon of the oracle texts", in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (eds.), Early Chinese Religion, Part One: Shang through Han (1250 BC–220 AD), Brill, pp. 41–102, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004168350.i-1312.11, ISBN 978-90-04-17208-1.

- Jing, Zhichun; Tang, Jigen; Rapp, George; Stoltman, James (2013), "Recent discoveries and some thoughts on early urbanization at Anyang", in Underhill, Anne P. (ed.), A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 343–366, doi:10.1002/9781118325698.ch17, ISBN 978-1-118-32578-0.

- Keightley, David N. (1978), "The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou Chronology", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 38 (2): 423–438, doi:10.2307/2718906, JSTOR 2718906.

- ——— (1983), "The Late Shang state: when, where, and what?", in Keightley, David N.; Barnard, Noel (eds.), The Origins of Chinese civilization, University of California Press, pp. 523–564, ISBN 978-0-520-04229-2.

- ——— (1985) [1978], Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05455-5.