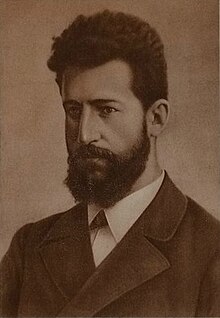

Lado Ketskhoveli (Georgian: ლადო კეცხოველი; 14 January 1877, in Gori – 30 August 1903, in Tiflis) was a Georgian writer and revolutionary who was one of the first people to introduce Joseph Stalin to Marxism.[1][2] He was one of the few people that Stalin looked up to because of his "astonishing, outstanding talents" and a person whom Stalin called himself a "disciple" to.[3]

Biography

editEarly years

editThe son of a Gori priest, Lado met Stalin while living in Gori and quickly joined the church school that he attended. He had been attending a better school, the Tiflis Seminary, but had been sent back to the church school after orchestrating a protest and a strike at the Seminary. It was due to Lado's early influence that Stalin first wanted to become an administrator in order to make a better difference. Lado also took Stalin, when Stalin was only thirteen, to a bookstore and bought him a copy of On the Origin of Species by Darwin.[3]

Joining the Mesame Dasi

editAfterwards, while Stalin was attending the Tiflis Seminary at an older age, Lado tried to enter the Kiev Seminary after having gotten himself and all 82 of the other students expelled from the Tiflis Seminary from their strike four years earlier. He was able to enter the Kiev Seminary, but quickly suspicion fell on him and he was arrested. Then he was let out again on police surveillance, but managed to get away from their watch and return to Tiflis, where he met up with Stalin once more.[2]

He then showed Silibistro "Silva" Jibladze, a rather famous man who, in years past, had beaten up the rector of the Tiflis Seminary, to Stalin. Jibladze, Noe Jordania, and some others, had formed a group known as the Mesame Dasi, the "Third Group", in 1892. The group was a socialist party made up of Georgians. They had all come together in Tbilisi and taken over the newspaper known as Kvali, using it to spread revolutionary messages to the workers in the area. Stalin wished to help with the newspaper and went to the leader of the group, Jordania, to ask to do so. He was swiftly and rudely denied. Lado, disliking Jordania's attitude almost as much as Stalin, took Stalin to the Russian workers' circles that had been forming in Tbilisi. It was here, thanks to Lado, that Stalin would begin to become a true revolutionary.[3]

Organizing worker strikes

editDuring the latter part of 1899, Lado began organizing a full-scale strike by the workers in Tbilisi and he was eagerly assisted by Stalin. They began the strike on New Year's Day and Lado managed to bring the city to a grinding halt by having the train drivers join him in the strike. However, this was not just let go by the government, as the secret police had been watching their activities for a while. Stalin was arrested by them in January 1900 under the pretense that his father, Beso, had not been paying his taxes in his local village. But the revolutionary group was able to work together to raise the money for his bail. When he finally returned, both Lado and Stalin continued to work on organizing strikes.[3]

Later years

editIn January 1900, by decision of the leading group of the Tiflis organization of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, Ketskhoveli went to Baku with the aim of uniting local social democratic circles and creating an underground printing house and became one of the founders of the Baku Committee of the RSDLP.

On May Day of 1900, Stalin began to organize a secret meeting of the revolutionaries, considering it was the day that labor usually demonstrated. However, even with his meticulous secrecy, he was found out and the secret police first came to Lado, but he managed to escape to Baku, leaving Stalin to take his place. No arrests came of the incident, though Stalin did become marked by the police as a leader of the group.[3]

In 1901, Lado began to work with Abel Yenukidze and Alexander Tsulukidze in order to print a radical newspaper called Brdzola, "Struggle". They were able to begin printing it on an illegal printing press in Baku.[3][4][5]

Death and legacy

editFinally, in 1903, Lado was arrested in Baku and put in the Metekhi Fortress, a political prison run by the Tsars. While he was there, one day, he had begun yelling "Down with Autocracy" at the guards and, in return, one of them shot him in the heart.[3][6] Afterwards, there was no ceremony at his burial, but both Dzhugashvili and Lado's younger brother spoke at his funeral. His brother said that Lado's last words were, "They will pay dearly for my death."[7]

Because of the great respect and admiration that Stalin held for Lado, one of the few people he ever considered an equal, he had a collection of articles created in 1938 that were dedicated completely to Lado, including a paean made by Lavrentiy Beria. In addition, commemorative articles continued to be made by various newspapers from 1938 onward, until the end of the war, and, in 1953, a monograph was made to immortalize his exploits.[2]

In the town of Arali, a statue of Lado was erected in front of the House of Culture. There also used a be a collective farm nearby the town that was named after Lado.[8]

References

edit- ^ Rayfield, Donald (13 December 2005). Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him Google Books. ISBN 978-0-375-75771-6.

- ^ a b c Davies, Sarah; Davies, Sarah Rosemary; Harris, James R (2005). Stalin: a new history – Google Books. ISBN 978-0-521-85104-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Montefiore, Simon Sebag (14 October 2008). Young Stalin – Google Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-9613-8.

- ^ Service, Robert (4 April 2005). Stalin: a biography – Google Books. ISBN 978-0-674-01697-2.

- ^ Rappaport, Helen (1999). Joseph Stalin: a biographical companion – Google Books. ISBN 978-1-57607-208-0.

- ^ Jones, Stephen F (2005). Socialism in Georgian colors: the European road to social democracy, 1883–1917 – Google Books. ISBN 978-0-674-01902-7.

- ^ Shukman, Harold (2003). Redefining Stalinism – Google Books. ISBN 978-0-7146-8342-3.

- ^ "Report on the Village of Arali – Human Rights". humanrights.ge. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2010.