Kyrkoplikt (literally: 'church duty') was a historical form of punishment, practiced in Sweden and Finland. It was a form of public humiliation in which the condemned was made to confess and repent of their crime before being rehabilitated and spared further punishments. It could be sentenced by the church or by a secular court, and performed by the church. The concept of "church duty" thus does not have anything to do with an obligation to go to church, in spite of the name (kyrkogångsplikt, literally 'church attendance obligation').

History

editThe kyrkoplikt originated from the confession and repentance within the Catholic church during the Middle Ages: after having committed a more serious crime, the criminal was cast out of their parish congregation, and was only rehabilitated after having repented of their sin.

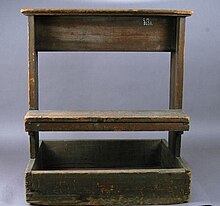

In the Swedish Church Ordinance 1571, kyrkoplikt consisted of the corporal punishments meted out within the sphere of public humiliation, such as pillorying, the stocks, corporal punishment and similar punishments, or fines. Finally, the condemned were made to stand upon the pliktpallen ('duty stool') – also called the skampallen ('shame stool') – during a church sermon, when their crimes were described, after which they repented and were rehabilitated, in many cases after having been subjected to other form of punishments. The punishment could be meted out by both the church as well as by a secular court, who both had the right to handle criminals.

By the Swedish Church Law 1686, the church was no longer allowed to handle court cases and judge criminals and the right to sentence criminals to kyrkoplikt was reserved for the legal courts of the state.

In 1741, a legal reform created two forms of kyrkoplikt: uppenbar kyrkoplikt (lit. 'obvious church duty') and enskild kyrkoplikt (lit. 'private church duty').

On 4 May 1855, kyrkoplikt and all forms of public humiliation were abolished in Sweden. In Finland, the same reform was introduced in 1864.

Uppenbar kyrkoplikt

editUppenbar kyrkoplikt (literally: 'obvious church duty') was the original form of kyrkoplikt. Uppenbar kyrkoplikt was meted out for all forms of criminalized acts: theft, adultery, abuse, witchcraft and those pardoned from the death sentence.

By the reform of 1741, uppenbar kyrkoplikt was abolished for sex outside of marriage. All sexual acts outside of marriage were formally illegal, but as an illegal sexual act was normally only exposed when it resulted in pregnancy, and the male party could deny having engaged in the act while the participation of the pregnant female in the act was undeniable; uppenbar kyrkoplikt was in practice mostly used upon unmarried mothers.[1] This was viewed as a problem in the Riksdag of the Estates, because the social stigma caused by uppenbar kyrkoplikt's way of exposing the women, who felt themselves socially branded, was found to be a significant cause of infanticide performed by unmarried women desperate to do anything to avoid having their reputation ruined by the shame. Despite opposition from the clergy, uppenbar kyrkoplikt was abolished for sexual crimes in an attempt to prevent infanticide.[2] This reform was followed by the Barnamordsplakatet in 1778.

Enskild kyrkoplikt

editEnskild kyrkoplikt (literally: 'private church duty') meant that the criminal was made to confess and repent in the sacristy, before or after service, in private before the priest and only a handful of witnesses selected by the priest.

This was used for the crime of sex outside of marriage, as well as minor crimes such as insignificant forms of theft.

References

edit- Nordisk familjebok / 1800-talsutgåvan. 9. Kristendomen - Lloyd

- Carlquist, Gunnar, red (1933). Svensk uppslagsbok. Bd 16. Malmö: Svensk Uppslagsbok AB. Sid. 496