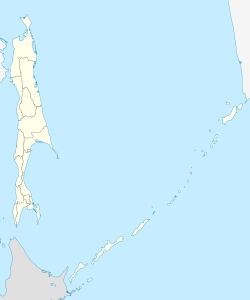

Korsakov (Russian: Корсаков; Japanese: 大泊, Ōdomari) is a town and the administrative center of Korsakovsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located 42 kilometers (26 mi) south from Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, on the coast of the Salmon Cove in the Aniva Bay. The town has a population of 33,526 as of the 2010 census.

Korsakov

Корсаков 大泊 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 46°38′N 142°46′E / 46.633°N 142.767°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Sakhalin Oblast[1] |

| Administrative district | Korsakovsky District[1] |

| Founded | 1853 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor[2] | Lada Mudrova[2] |

| Elevation | 30 m (100 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 33,526 |

| • Capital of | Korsakovsky District[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Korsakovsky Urban Okrug[4] |

| • Capital of | Korsakovsky Urban Okrug[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+11 (MSK+8 |

| Postal code(s)[6] | 694020 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 42435[7] |

| OKTMO ID | 64716000001 |

| Website | www |

History

editLittle is known of the early history of Korsakov. The site was once home to an Ainu fishing village called Kushunkotan (in Russian sources, Tamari-Aniva), which was frequented by traders of the Matsumae clan from as early as 1790.[8][9] On 22 September 1853, a Russian expedition, commanded by Gennady Nevelskoy, raised the Russian flag at the settlement and renamed it "Fort Muravyovsky", after Governor-General of Eastern Siberia Nikolay Muravyov.[10][11][12] Nevelskoy left detailed recollections of the landing. He encountered a predominantly Ainu population (at least 600 people;[13] another source mentions only 300 Ainu inhabitants[10]) as well as Japanese nationals who, judging by Nevelskoy's account, exercised authority over the native inhabitants. At the time of Nevelskoy's arrival, the village featured several standing structures, Nevelskoy calls them "sheds", and even a Japanese religious temple. The villagers supposedly welcomed the Russians after they learned about their mission (protecting them from foreign incursion). The veracity of this account is in doubt, both because Nevelskoy had ulterior motives for claiming that he was "welcomed" by the inhabitants, and also because it is not clear to what extent the Russians were able to make themselves understood.[14] The Russians abandoned the settlement on May 30, 1854, allegedly because their presence there, at the time of the Crimean War, raised the specter of Anglo-French attack, but returned in August 1869, now renaming the town "Fort Korsakovsky," in honor of then-Governor General of Eastern Siberia Mikhail Korsakov.[12] Lingering territorial conflict between Japan and Russia has polarized scholarly opinion of Korsakov's early history, as each side tries to claim priority of early settlement to back up their respective territorial claims in the broader region. In 1875, the whole Sakhalin including the village was ceded to Russia, under the Treaty of Saint Petersburg.

While under Russian administration Fort Korsakovsky was an important administrative center in Sakhalin's penal servitude system and a final destination for hundreds of prisoners from European Russia, sentenced to forced labor for particularly serious crimes. Such prisoners and their families comprised early settlers of Fort Korsakovsky until its hand-over to the Japanese. Prominent Russian writers, including A.P. Chekhov and V.M. Doroshevich, visited Korsakovsky and left keen observations of its unsavory trade.

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, a naval engagement, the Battle of Korsakov, took place off the town in August 1904. In 1905, Japan conquered Sakhalin in the late stages of the war, and southern Sakhalina, including Korsakovsky, was handed over to Japan in 1905 after Russia's defeat in the war. The Russians burned the wooden town before the hand-over. Upon the ashes of Fort Korsakovsky the Japanese built a stone-clad modern city with paved streets and electricity, renaming it Ōtomari (大泊), a translation of the Ainu words "Poro-an-tomari" (big harbor). The town was temporarily the capital of Karafuto Prefecture between 1905 and 1907. While in Japanese hands the town grew substantially. A penal colony under Russia's administration, Ōtomari maintained the practice of forced labor: the Japanese brought thousands of ethnic Koreans to Ōtomari as workers. Korsakov's present-day Korean population is descended mainly from those labor conscripts.

In the closing stages of World War II, the Soviet Union conquered Karafuto Prefecture, and Old Ōtomari was burned down substantially upon the entry of Soviet troops. After the war, Japan ceded Karafuto, including, Ōtomari, to the Soviet Union. The Japanese population was mostly repatriated by 1947, though a few remained, along with a sizable Korean population. The old bank, a Japanese bank building (originally, the Ōtomari Branch of Hokkaido Takushoku Bank) remains standing, though efforts to convert it into a museum came to nothing for lack of funds. Other Japanese sites and memorials were all destroyed, including a Shinto shrine and a monument to Prince Hirohito, who had visited Ōtomari on an inspection tour. An interesting sample of Japanese monuments can now be seen near Prigorodnoye, which was known as Merei before 1945. During the Cold War Korsakov was also the site of two Naval airfields.

Administrative and municipal status

editWithin the framework of administrative divisions, Korsakov serves as the administrative center of Korsakovsky District and is subordinated to it.[1] As a municipal division, the town of Korsakov and seventeen rural localities of Korsakovsky District are incorporated as Korsakovsky Urban Okrug.[4]

Economy

editAccording to a 1 November 1945 Soviet report, the town had:

- two refrigerators for fish processing

- a paper factory

- a factory to extract salt from sea water (production capacity 20 thousand tons per year)

- a sulphur-alcohol plant

- 7 sake production facilities

- 2 timber plants

Up until the 1990s, Korsakov was a major base for the Russian Far Eastern fishing fleet. It was the home of the Base for Ocean Shipping, Baza Okeanicheskogo Rybolovstva (BOR), which went bankrupt during the post-Soviet recession. The thousands of fishermen employed by the BOR continued their work for private fishing companies, which usually operated small fishing boats not far off the coast, often without licences. The catch (primarily crab) was sold in Japan for hard currency, mainly in Wakkanai. Fishermen purchased Japanese electronics and used cars. This semi-illicit, semi-barter economy had a certain positive economic effect on Korsakov, though it contributed to organised crime.

Among other large economic units in Korsakov was a factory, which produced cardboard boxes; Fabrika Gofrirovannoy Tary. The factory operated on run-down equipment, possibly left over from the Japanese times, and was visible to anyone in Korsakov, as it featured a tall chimney. Gennady Zlivko, formerly a mayor of the town, was once a director of this factory. It has long since gone bankrupt, and its tall chimney, no longer emitting black smoke, is the only thing that reminds one of the earlier years of Korsakov's economy.

Korsakov is also the closest town to the huge LNG plant, constructed within the framework of the Sakhalin-2 project.

Demographics

edit

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: 1897 excludes the district.[15] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curiously, at the early stage of settlement (late 1890s), men in Korsakovsky outnumbered women almost by a factor of ten. In 1897, for example, 1,510 males and 192 females lived in the town. This imbalance was due to the majority of Korsakov's inhabitants being prisoners and prison-keepers; in both males predominated. The ethnic make-up, by mother tongue, was 63.2% Russian, 10.5% Ukrainian, 7.3% Tatar, 6.3% Polish, 2.2% Japanese, 2.0% Belarusian, 1.3% German, 0.9% Lithuanian, 0.8% Circassian.[16] The district of Korsakovsky (in 1897 covering 6,6762 square verst) had a population of 4,659 males and 2,194 females.[17]

The town's population was at its highest (just over 45,000) in the late 1980s, whereupon it experienced significant decline as inhabitants fled economic downturn by moving to neighboring Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk or to continental Russia. Korsakov's population remains in decline, although no longer as sharp as in the 1990s.[18]

The demographic make-up is primarily ethnic Russian with a large ethnic Korean minority.

Sport

editSights

editAmenities include a fairly run-down and expensive hotel ("Alfa") next to the former park. The beach is easily accessible by car (Okhotsk, about 1 hour and Prigorodnoye, about 30 minutes). The formerly well-kept beach at Vtoraya Pad has now deteriorated into a messy junkyard.

Winter sights include skating at the city stadium and excellent cross-country skiing past the former sea weed plant (Na Agarike). No facilities exist for downhill skiing.

The town features a museum with an exhibit describing the local frontier history, and the Japanese possession of the city (1905–1945). Local market on the Sovetskaya Street offers great strawberries in the summer, and nicely prepared Korean delicacies (kimchi and the local hit, the paporotnik, all year around).

Foreign tourists from certain countries or transiting via cruise ship or air are now able to visit the town without a visa for 72 hours.[20][21]

Politics

editThe town has its executive (the mayor's office or "municipal administration"), and its legislature (Duma). In practice, the Duma exercises fairly limited influence over the executive.

List of mayors:

- Lada Mudrova (since 2008)

- Gennady Zlivko (2004–2008): removed by court decision

- Alexander Svoyakov (acting, 2004): lost election to Gennady Zlivko

- Valery Osadchy (1993–2004): resigned

- Yury Savenko (1991–1993): resigned

Transportation

editKorsakov is located about 30 kilometers (19 mi) from the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Airport. Regular bus and minibus services connect Korsakov with the capital city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, though not with the airport. A passenger ferry service between Korsakov and Wakkanai, Hokkaidō, Japan, across the Aniva Gulf, was re-established in 2016 and is in operation between June and September of each year. The passenger ferry service is operated by the Commonwealth of Dominica flagged vessel Penguin 33, which is High-speed craft owned by Penguin International Limited, a Singaporean-owned publicly listed company.[22][23]

The Japan National Rail passenger ferry service previously operated a service from Wakkanai, called "Chihaku-Renrakusen (Chihaku Ferry Service)" from 1923 to 1945, which was linked to Japan's national rail network and to Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (then called Toyohara). The old narrow-gauge Japanese railroad still runs along the scenic coastline, with sporadic rail service.

There are several bus lines servicing the urban area and a number of villages in the proximity.

The city has a large seaport.

International relations

editTwin towns and sister cities

editKorsakov is twinned with:

Notable people

edit- Alexandr Anatolyevich Romankov (born 7 November 1953, Korsakov, Sakhalin) He trained at Dynamo in Minsk and won a gold medal, two silver medals and two bronze medals at the three Olympic Games that he competed in between 1976 and 1988.[24]

- Georgi Kulikov (born 11 June 1947, Korsakov, Sakhalin) is former butterfly and freestyle swimmer who competed in the 1968 Summer Olympics and in the 1972 Summer Olympics. He won two medals representing the Soviet Union at two Olympic Games.

References

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e Law #25-ZO

- ^ a b "Presentation of project: "Perinatal medicine: positive maternity" Date: June 1, 2011 Access Date: February 4, 2014". Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ a b c Law #524

- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ Телефонные коды Сахалина - Dialing codes of Sakhalin Archived December 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ The Conquest of Ainu Lands, Brett L. Walker, ISBN 0-520-24834-1, ISBN 978-0-520-24834-2

- ^ Coast of Kushunkotan Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, 1873 map.

- ^ a b The Occupation of Southern Saghalin by the Russians in 1853–54, Akizuki Toshiyuki, Hokkaidō University.

- ^ 久春古丹に於ける露人の堡塞 Archived June 27, 2005, at the Wayback Machine (The garrison of Russians at Kushunkotan), Jirosuke Yoda, 1854.

- ^ a b "История Корсакова в 19 веке - Официальный сайт муниципального образования "Корсаковский городской округ"". Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ^ Gennady Nevelskoy, Podvigi Russkikh Morskikh Ofitserov Na Kraynem Vostoke (1878), p. 252, footnote.

- ^ Gennady Nevelskoy, Podvigi Russkikh Morskikh Ofitserov Na Kraynem Vostoke (1878), pp. 249–255). Also available in electronic format: http://orel3.rsl.ru/meeting_on_fr/12/[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_gub_97.php?reg=77. This excludes the district.

- ^ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской империи, 1897 г. (in Russian). Vol. LXXVII. 1904. pp. 34–37.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей".

- ^ "Народная энциклопедия "Мой город". Корсаков (Сахалинская область)".

- ^ "Команда из Корсакова стала победителем чемпионата области по хоккею с мячом. Сахалин.Инфо".

- ^ Visas and customs in Russia

- ^ Visa-Free Entry for Cruise Passengers

- ^ 稚内市. "Sakhalin regular line / Wakkanai-shi". www.city.wakkanai.hokkaido.jp.e.dh.hp.transer.com. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "HSL 北海道サハリン航路株式会社". hs-line.com (in Japanese). Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ https://olympics.com/en/athletes/aleksander-romankov [bare URL]

Sources

edit- Сахалинская областная Дума. Закон №25-ЗО от 23 марта 2011 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Сахалинской области», в ред. Закона №62-ЗО от 27 июня 2013 г. «О внесении изменения в статью 10 Закона Сахалинской области "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Сахалинской области"». Вступил в силу 9 апреля 2011 г.. Опубликован: "Губернские ведомости", №55(3742), 29 марта 2011 г. (Sakhalin Oblast Duma. Law #25-ZO of March 23, 2011 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Sakhalin Oblast, as amended by the Law #62-ZO of June 27, 2013 On Amending Article 10 of the Law of Sakhalin Oblast "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Sakhalin Oblast". Effective as of April 9, 2011.).

- Сахалинская областная Дума. Закон №524 от 21 июля 2004 г. «О границах и статусе муниципальных образований в Сахалинской области», в ред. Закона №45-ЗО от 27 мая 2013 г. «О внесении изменения в Закон Сахалинской области "О границах и статусе муниципальных образований в Сахалинской области"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2005 г. Опубликован: "Губернские ведомости", №175–176(2111–2112), 31 июля 2004 г. (Sakhalin Oblast Duma. Law #524 of July 21, 2004 On the Borders and Status of the Municipal Formations in Sakhalin Oblast, as amended by the Law #45-ZO of May 27, 2013 On Amending the Law of Sakhalin Oblast "On the Borders and Status of the Municipal Formations in Sakhalin Oblast". Effective as of January 1, 2005.).

External links

edit- Korsakov travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Unofficial website of Korsakov Archived January 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)