Konstantin Andreyevich Somov (Russian: Константин Андреевич Сомов; 30 November [O.S. 18 November] 1869 – 6 May 1939)[1] was a Russian artist associated with the Mir iskusstva ("World of Art") movement that began in the last decade of the 19th century. After the Russian Revolution, he eventually emigrated to Paris, along with other prominent figures in the Russian arts. In his private life, he had a longtime, younger male companion, Methodiy Lukyanov, and an ambiguous artistic and personal relationship with a young boxer, Boris Snezhkovsky, whom he painted many times. In the 21st century, his paintings have sold in the millions of dollars. In 2007, Somov's The Rainbow sold at Christie's London for GBP 3,716,000 (USD 7.44 million; equivalent to GBP 6.51 million [USD 13 million] in 2023[2]), an auction record for a Russian work of art.

Konstantin Somov | |

|---|---|

Константин Сомов | |

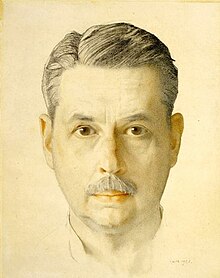

Self-portrait (1921) | |

| Born | Konstantin Andreyevich Somov November 30, 1869 |

| Died | May 6, 1939 (aged 69) |

| Education | Imperial Academy of Arts (elected Member, 1914[1]); Académie Colarossi |

| Known for | Painting, Porcelain, Erotic art |

| Notable work | Le Livre de la Marquise (1907-1919); The Rainbow (1927); The Boxer (1933) |

| Signature | |

Biography

editFamily and education

editKonstantin Somov was born on 30 November 1869 in Saint Petersburg. He was the second son of Andrei Somov, an art historian and senior curator at the Hermitage Museum. His mother, Nadezhda Konstantinovna, came from the noble family of the Lobanovs. She was well-educated and a musician. She instilled in her children a love of theatre, music, and painting. The Somovs had a large private collection of old prints, paintings, and drawings. Young Konstantin dreamed of becoming an artist from a very young age.[3]

While a student at the Karl May School in Saint Petersburg, Somov became close friends with Dmitry Filosofov. Alexandre Benois, also a student, later wrote that "Some kind of magic circle separated them from the others." Later, Filosofov was sent to Italy due to illness, and Somov, who had a hard time studying science, was withdrawn from the school by his father. At the age of 20, Somov entered the Imperial Academy of Arts, where he studied under Ilya Repin, from 1888 to 1897. While at the academy, he met Sergei Diaghilev and Léon Bakst.[3]

Somov traveled to Italy in 1890 and 1894, and the two winters he spent in Paris, in 1897 and 1898, he later recalled as the happiest days of his life.[4]

Somov's first major success came a year before graduation from the academy. Somov and Benois spent the summer of 1896 at a dacha near Oranienbaum, in the village of Martyshkino. The landscapes and sketches he created there were highly praised by critics and colleagues. That year, he also created illustrations for the works of E. T. A. Hoffmann.

In 1897, he successfully completed his studies at the academy and went to Paris to continue his education at the Académie Colarossi.[5]

Mir iskusstva, career success

editIn 1898 and 1899, Somov was a founding member of Mir iskusstva (World of Art), a Russian artistic movement and magazine (edited by Sergei Diaghilev) that was a major influence on the Russians who revolutionized European art during the first decade of the 20th century. He served on the editorial board and contributed illustrations and designs.[3][6]

For three years, from 1897 to 1900, he worked on his early masterpiece Lady in Blue (a portrait of Elizaveta Martynova), painted in the manner of 18th-century portraitists.

Along with landscape and portrait painting, watercolors, gouache, and graphics, Somov worked in the field of small plastic arts, creating exquisite porcelain compositions.

He had his first solo exhibition in Saint Petersburg in 1903 (162 paintings, sketches, and drawings).[7] Also in 1903, 95 of his works were exhibited in Hamburg and Berlin. In 1906, in a group show of Russian artists organized by Diaghilev, he exhibited 32 works at the Salon d'Automne in Paris.[8][9] His work was particularly appreciated in Germany, where the first monograph on him, by Oskar Bie, was published in 1907.[10]

During the 1910s, Somov executed rococo harlequin scenes and gallant scenes, as well as illustrations for books including poems by Alexander Blok.[3][1]

Somov's modern idols were the English Pre-Raphaelites, Aubrey Beardsley, and James McNeill Whistler. His favorite masters of the past were French rococo artists such as Antoine Watteau, Nicolas de Largillière, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and François Boucher. His favorite poet was Paul Verlaine.[3][11]

"By 1910, Somov was a famous and accepted painter, and just as every household of taste had a landscape by Benois and a dress designed by Bakst, so it had a miniature by Somov [...]. By 1917, judging by the high auction prices for his work [...] Somov must have been a rich man."[12]

The colorful, festive visions created by Somov had a darker side. The Russian poet Mikhail Kuzmin noted:

Some kind of demon is constantly pushing the artist, as if a piece of a magic mirror from Andersen's fairy tale had hit him in the eye [...]. Anxiety, irony, the puppet theatricality of the world, the comedy of eroticism, the variegation of masquerade freaks, the false light of candles, the sorcery-skull hidden under rags and flowers, automatic love poses, deadness and creepiness of amiable smiles—this is the pathos of a number of Somov's works. Oh, how not cheerful is this gallant Somov! What a terrible mirror he holds up to the laughing holiday![3]

Alexandre Benois called Somov "one of the most delicate poets and one of the most refined masters of modern painting", even as he classified Somov's work as decadent and presciently wrote that "only with the decline of a culture do such figures appear as that of Somov [...]. In virtue of all his merits and failings Somov may count [...] upon one of the most prominent places in the history of Russian painting [...] no other artist of the beginning of the twentieth century has mirrored with greater faithfulness the peculiar charm of our super-refined epoch, which knows so much and believes so little."[13]

-

Rainbow, 1897

-

Dame ôtant son masque, by 1906

-

Cover, Konstantin Balmont's Zhar-Ptitsa, 1907

-

A Ridiculed Kiss, 1908

-

Title page, Alexander Blok's Theatre, 1909

-

Pierrot and lady, 1910

-

Love letter, 1911

-

La Petite Langue de Colombine, 1915

Le Livre de la Marquise

editFrom 1907 to 1919, Somov drew over 120 ink drawings, some merely suggestive, some quite explicit, for multiple editions of Le Livre de la Marquise. The book is "an anthology of eighteenth century erotic French poetry and prose, and contains 56 works by some 50 authors, including excerpts from works by Voltaire, Parny, fragments from Les Liaisons dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos and individual episodes from Casanova's Memoirs".[14]

Among connoisseurs, Somov was given the nickname "Sodomov", to which the artist responded "The essence of everything is eroticism. Therefore art is unimaginable without an erotic basis."[14] Commenting on one edition, the Russian academician A. A. Sidorov said that Somov "seemingly permitted himself everything from which Russian art had abstained [...] the best of today's graphic artists has genuinely surpassed himself".[15]

The most explicit edition was published after the Russian Revolution abolished censorship in 1917, which "gave Somov the opportunity of publishing a luxurious edition of the book with bolder illustrations [...]. One of the best printing houses in St Petersburg, R. Golike & A. Vilborg & Company" produced 800 copies. "In addition, part of the run was printed in a special collectors' version with additional indecent illustrations which might even be described as pornographic."[14]

Russian Revolution, move to Paris

edit"Somov's reaction to the revolution was negative [...]. One by one his colleagues emigrated, his clientèle disappeared overnight, and his retrospective pictures became meaningless to the new artistic consciousness."[16] He, nonetheless, became a professor at the Petrograd Free Art Educational Studios (the renamed Imperial Academy of Arts) in 1918, and, in 1919, he celebrated his 50th birthday jubilee with a one-person exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery.[1]

Living conditions deteriorated in Russia. His apartment was nationalized, and he was later evicted. He struggled to retain the rights to his art.

Somov left Russia in 1923 to accompany the seminal exhibition of Russian Art that took place in New York in 1924.[11] In the United States, he became close to the family of Sergei Rachmaninoff and painted portraits of the composer and his daughter. He never returned to his homeland, declaring Soviet Russia "absolutely alien to his art". He chose instead to settle in Paris in 1925, joining the community of Russian emigre artists, writers, dancers, and musicians that included his old friends Benois, Léon Bakst, and Zinaida Serebryakova.

An idea of the polyglot cultural milieu of Somov's Paris can be gleaned from a letter to his sister dated 19 January 1931:

Yesterday I dined at the Leons' with Henrietta and with the famous writer Joyce, who created a stir with his book Ulysses, incomprehensible and rather scandalous. At one time I tried to read it, but out of 700 pages (!) I read, with difficulty and without any pleasure, 150 pages and even the last chapter, in which there are 45 pages and it is all one phrase without one dot, comma, etc. Can you imagine! But this book gave him fame and prosperity. The Leons have long wanted to introduce me to him—before, I knew only his son, a young graduate student and swimmer. My impression of the father is not very great. Firstly, he is a wild alcoholic and his wife, who was present, trembled over him, no matter how drunk he was; secondly, he is almost completely blind, he sees out of the corner of one eye. Not very talkative, and slow.[17]

Private life

editAs a child, Somov preferred to play with dolls and make costumes for them, and it was easiest for him to be friends with girls.[3]

Despite his social connections, travels abroad, and his active participation in the art scene of turn-of-the-century Russia, Somov as a young man suffered from loneliness, as evidenced by a letter dated 14 February 1899 when Somov was 29 to his friend and colleague Elizaveta Zvantseva:

Unfortunately, I still have no romance with anyone—flirting, perhaps, but very light. But I'm tired of being without romance—it's time, otherwise life passes by, and youth, and it becomes scary. I terribly regret that my character is heavy, tedious, gloomy. I would like to be cheerful, easy-going, amorous, a daredevil. Only such people have fun, those not afraid to live![18]

In 1910, when Somov was 40, he met 18-year-old Methodiy Lukyanov, who became Somov's closest companion and became part of the Somov family. He also helped Somov run his household and organize exhibitions, and served as Somov's trusted advisor and critic.

During World War I, the homosexual British novelist Hugh Walpole worked as a British correspondent in Russia. While in Saint Petersburg in 1915, Walpole formed a close friendship with Somov and, in February 1916, moved into Somov's home. Walpole left Russia on 7 November 1917, the day the October Revolution began.[19]

In 1918, Somov painted a large portrait of Methodiy Lukyanov sitting on a sofa in pajamas and a dressing gown, which is now in the Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg.

In the spring of 1931, in Paris, Lukyanov fell ill with tuberculosis. In great distress, Somov wrote to his sister in Russia:

Every minute of my life is now torment—although I do everything I need to—eat, talk with visitors, even work a little—the thought of Methodius and the upcoming separation does not leave me. Now I absorb into myself his face, his every word, knowing that soon I will not see him again [...]. Yesterday, lying on a mattress, on the floor by his bed, I tried to pray mentally—It's me! God, if you exist and care about people, prove, save Methodius to me, and I will believe in you! But it's all in vain.[17]

After a year-long decline, a great deal of suffering, and an agonizing final day, Lukyanov died on 14 April 1932. In a letter to his sister, Somov wrote, "Methodius was buried yesterday [...] there are no words, how it was for me to return home alone [...]. Today I began to live a new life—without Methodius."[17]

In June 1930, Somov met Boris Mikhailovich Snezhkovsky (born 23 July 1910), who modeled for Daphnis when Somov created illustrations for Daphnis and Chloe. Snezhkovsky was henceforth referred to by Somov in his diaries as "Daphnis". Mikhail Seslavinsky in his Randevu (Rendezvous) quotes Somov speaking about Snezhkovsky: "My model, a Russian, 19 years old, turned out to be clever, well-educated and nice." During the course of the 1930s, Somov went on to paint his model on numerous occasions, both clothed and nude.

In a letter dated 28 February 1933, Somov wrote to his sister: "Two days ago, I finished a portrait in oil, a nu (half-length), and afterwards I painted a still life beside him: a mirror, behind him a chest of drawers, on which lay his shirt and vest, with a pair of boxing gloves hanging on the wall—the painting is not bad." Known as The Boxer, Somov's "not bad" portrait of Snezhkovsky was auctioned at Christie's London in 2011, where it realized GBP 713,250 (USD 1.14 million; equivalent to GBP 1.1 million [USD 1.76 million] in 2023[2]).[11]

-

Illustration for Daphnis and Chloe (Snezhkovsky as model), 1930

-

The Boxer (portrait of Snezhkovsky), 1933

-

Somov and Snezhkovsky in 1934

-

Boris Snezhkovsky, 1934

-

Nude Youth (Snezhkovsky), 1937

Somov was known for his ironic and self-deprecating humor. "I would like to become Ingres", he once said. "Or if not Ingres, then at least his little toe."[3]

Somov died in 1939 at the age of 69. He was buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery, south of Paris.

Legacy

editOn June 14, 2007, Somov's landscape The Rainbow (1927) was sold at Christie's London for GBP 3,716,000 (USD 7.44 million; equivalent to GBP 6.51 million [USD 13 million] in 2023[2]), an auction record for a Russian work of art.[20][21]

In 2016, Russian art historian Pavel Golubev founded the Somov Society to preserve, study, and popularize the heritage of Konstantin Somov.[22]

Somov's diary (Dnevik) for the years 1917–1927, edited by Golubev, was published by Dmitrii Sechin, Moscow, in 2017, 2018, and 2019; the three volumes total over 2,100 pages.

The publication project that Pavel Golubev embarked on is a breakthrough in Somov scholarship, and its significance cannot be overstated [...]. Golubev's pioneering publication gives the reader unabridged access to the inner workings of Somov's creative process and unabashedly exposes the homoerotic context of his entire oeuvre. In addition to brilliantly deciphering and publishing a text written in minute and incomprehensible handwriting, Golubev overcomes a few additional textological challenges. For example [...] Somov's nephew [...] before he transferred the originals to the State Russian Museum in the late 1960s and early 1970s [...] crossed out potentially dangerous political facts and opinions and homosexual content, most of which the editor managed to restore [...]. Somov rendered sexual terms and descriptions in foreign languages, and after 1930 he mostly used a primitive shift cipher to encode such fragments [...]. The contents of the volumes to follow promise to be even more fascinating as so much less is known about Somov's émigré years.[23]

In 2019, to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth, the Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg mounted the exhibition Konstantin Somov, which brought together over 100 works by the artist.[24]

Also in 2019, Pavel Golubev curated the exhibition Konstantin Somov, Uncensored at the Odesa Fine Arts Museum in Ukraine.[22]

In 2022, Golubev presented the colloquium "The Lady with the Mask: Homosexuality in the Art of Konstantin Somov" at the University of Pennsylvania. From the abstract:

The same-sex erotic theme featured in many of his paintings and drawings, virtually open homosexual lifestyle, and anti-Bolshevik political views made Somov a disturbing personage for the Russian art historians. As a result, his artworks and biography were heavily censored in the Soviet time, and the issue of the artist's homosexuality until present day remains painful for his representation in Russia.[22]

Works

editPortraits

edit-

Anna Karlovna Benois, 1896

-

Self-portrait, 1898[25]

-

Alexander Blok, 1907

-

Mikhail Kuzmin, 1909[26]

-

Euphimia Pavlovna Nosova, 1911

-

Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1925

Paintings

edit-

Two peasant girls and a rainbow

-

Holiday near Venice

-

Two ladies in the park, 1919

-

View through a window, 1934

Illustrations for Le Livre de la Marquise

editNudes

edit-

Les Amants, 1931

-

Nude with Cigar, 1933

-

Homme nu allongé, 1938

-

The Lovers

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "Konstantin Somov". russia-ic.com. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anna Alyabyeva. "Константин Сомов: тёмная, холодная, старая страсть". regnum.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Bowlt (1970), p. 32.

- ^ Natasha Ignatova. "Романтик ушедшей эпохи: Константин Сомов". VTB. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Ryan and Thomas (2003), pp. 151-152.

- ^ Shcherbatov and Von Meck (1903).

- ^ Diaghilev (1906): list of works, pp. 106-108; images, pp. 27, 33, 58, 127.

- ^ Winestein (2005), p. 44: "Although it was only displayed for five weeks, the exhibit received great acclaim."

- ^ Bie (1907).

- ^ a b c "Lot 92: Konstantin Somov (1869-1939) The Boxer". christies.com. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Bowlt (1970), pp. 32-33.

- ^ Benois (1916), pp. 182-184.

- ^ a b c "MacDougall Auctions 28 ноября 2008 г." macdougallauction.com. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Sidorov (1923).

- ^ Bowlt (1970), p. 33.

- ^ a b c "Correspondence—A.A. Mikhailova, Page 1". konstantinsomov.ru. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ "Correspondence—E.N. Zvantseva". konstantinsomov.ru. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Hart-Davis, Rupert (1952); references to Somov (here spelled Somoff), pp. 132, 135-139, 143, 145, 149, and 152.

- ^ Varoli, John (14 June 2007), "Russian Sale Sets Record, 'Crazy' Prices at Christie's, London", Bloomberg, retrieved 20 September 2007

- ^ "Lot 60: Konstantin Andreevich Somov (1869-1939) The Rainbow". christies.com. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Pavel Golubev, "The Lady with the Mask: Homosexuality in the Art of Konstantin Somov"". upenn.edu. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Nazyrova (2018), p. 210-211.

- ^ "Konstantin Somov. On the 150th Anniversary of Birth". en.rusmuseum.ru/. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Ryan and Thomas (2003), pp. 151-152: "In 1898, Konstantin Somov (1869-1939), a founding member of the World of Art and, like so many of its associates, gay, painted himself in a way that made it clear that the 'Itinerant' manner that had ruled Russia for decades was coming under question. The bold cropping of the right margin of his Self-Portrait (Russian Museum) and the daring expanse of space on the left, which is dominated by the droop of the artist's hand—the means, of course, by which he practices his profession—have lost none of their power to startle. But it was the casual elegance and languid narcissism of the pose which announced that a time of unashamed enjoyment of the private sphere and a celebration of its pleasures, guilty no more, had come to Russian art and culture and that no more would the artist live artlessly in the world."

- ^ Anna Alyabyeva. "Константин Сомов: тёмная, холодная, старая страсть". regnum.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

About this portrait, Alexander Blok composed an epigram: In blush, flies and dandyism, in a fashionable undergarment, you hide your anachronism, singer and peer of Antinous.

Sources and further reading

edit- Anonymous (1918). "Modern Russian Painters Who Inspired the Russian Ballet", The Touchstone, vol. 1, no. 1, April, 1918, pp. 36-42.

- Aronian, Sona, guest editor. "Remizov, Part I", Russian Literature Triquarterly, no. 18, 1985; Somov is mentioned numerous times in this English translation of a memoir by Russian writer Aleksey Remizov. "Remizov, Part II" in RLT no. 19 is not available online.

- Benois, Alexander (1916). The Russian School of Painting, translated from Russian by Abraham Yarmolinsky, New York: A.A. Knopf, 1916.

- Bie, Oskar (1907). Constantin Somoff, Berlin: Verlag von Julius Bard, 1907.

- Bowlt, John E. (1970). "Konstantin Somov", Art Journal , Vol. 30, No. 1 (Autumn, 1970), pp. 31-36.

- Diaghilev, Sergei (1906). Exposition de l'Art Russe, catalogue of the Russian exhibition at the Salon d'Automne, Paris: Moreau frères, 1906.

- Green, Michael. Book review of Mir khudozhnika: Konstatin Andreevich Somov: Pis'ma, dnevniki, suzhdenkia sovremennikov, The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer, 1980), pp. 179-180.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert. Hugh Walpole, London: Macmillan, 1952; references to Somov (here spelled Somoff), pp. 132, 135–139, 143, 145, 149, and 152.

- Nazyrova, Djamilia (2018). Book review of Dnevnik: 1917-1923 by Konstantin Andreevich Somov, translated by Pavel Golubev, The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Spring 2018), pp. 210-211.

- Ryan, Judith, and Thomas, Alfred (2003). Cultures of Forgery: Making Nations, Making Selves, Routledge, 2003, pp. 151-152.

- Shcherbatov, Sergei, and Von Meck, W., editors (1903). Konstantin Somov/Constantin Somoff, exhibition catalogue, Saint Peterburg: Sovremennoe iskusstvo, 1903, 23 numbered pages, 60 plates, in Russian and French.

- Sidorov, A.A. (1923). Russian Graphic Art during the Years of the Revolution 1917-1922, Moscow: Dom Pechati, 1923.

- Williams, Harold Whitmore. Russia of the Russians, New York: C. Scribner's sons, 1915, p. 316.

- Winestein, Anna (2005). Dreamer and Showman: The Magical Reality of Alexandre Benois, Boston Public Library, 2005.

External links

edit- konstantinsomov.ru, includes a timeline biography and excerpts from Somov's correspondence (in Russian)

- Konstantin Somov at thesketchline.com