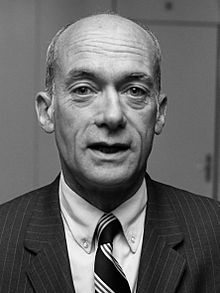

Kingdon Gould Jr. (January 3, 1924 – January 16, 2018) was an American diplomat, businessman, and philanthropist.[1] A Republican businessman, Gould was appointed by President Richard Nixon to serve as United States Ambassador to Luxembourg, a position he would hold from 1969 through 1972. In 1973, Gould was appointed as Ambassador to the Netherlands also by President Nixon, serving until 1976.

Kingdon Gould Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Ambassador to the Netherlands | |

| In office October 18, 1973 – September 30, 1976 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | J. William Middendorf |

| Succeeded by | Robert J. McCloskey |

| United States Ambassador to Luxembourg | |

| In office 1969–1972 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | George J. Feldman |

| Succeeded by | Ruth Lewis Farkas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 3, 1924 Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 16, 2018 (aged 94) North Laurel, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mary Thorne |

| Children | 9, including Kingdon Gould III |

| Parent(s) | Kingdon Gould, Sr. Annunziata Lucci |

| Education | Millbrook School Yale University |

| Occupation | Diplomat, businessman, philanthropist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 36th Mechanized Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | 2 Purple Hearts and 2 Silver Stars |

He is part of the fourth generation of the Gould family of financiers, philanthropists and diplomats, which includes his father Kingdon Gould Sr., grandfather George Jay Gould and great-grandfather Jay Gould, with associated generations of mothers, siblings, uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces and nephews.

Early life

editGould was the third child and the only son of Kingdon Gould, Sr., and his wife, Annunziata Lucci.[2] He attended Millbrook School in 1938[3] and graduated in 1942. He attended Yale University for two months in the spring of 1942[2] before serving in the United States Army in World War II and was the recipient of two Purple Hearts and two Silver Stars.[4] After returning from England in 1945,[3] he married Mary Bruce Thorne in 1946;[2] they had four sons, including Kingdon Gould III (born 1948), Frank, Thorne and Caleb, as well as five daughters, Lydia, Candida, Melissa, Annunziata and Thalia.[2][5] Gould returned to Yale to complete his undergraduate degree and then to study law, graduating in 1951.[3] He was the grandfather of United States Olympic cyclist Georgia Gould.[6]

Diplomatic career

editGould served as United States ambassador to Luxembourg from May 1969 to October 1972 during the Richard Nixon administration.[7] He later served as ambassador to the Netherlands from October 1973 to September 1976 under a second appointment by President Nixon, and continued serving through most of the Ford Administration.[8]

When President Nixon delivered his resignation speech in August 1974, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger was visiting with Gould in The Hague during his tenure as Ambassador to the Netherlands.[2] When discovering that Burger would swear in Gerald Ford to the presidency, Burger told Gould: "Do you understand the irony, Kingdon? That man [Nixon] appointed me to the highest office, and I wrote the opinion [that forced Nixon to turn over the Watergate tapes and papers as evidence in the trial of presidential aides accused of covering up the Watergate scandal".[2]

Later life and death

editFor many years Gould was business partner of Dominic F. Antonelli, Jr. in the Washington DC parking and real estate development PMI Parking Management Inc.[2] From 2013 until his death, he served as a trustee to the Baltimore Council on Foreign Affairs, a nonpartisan organization "dedicated to educating citizens about foreign affairs".[9] Gould's donations to Republican candidates and party organs attracted the attention of the media, as for instance in 2006 when the New York Times reported that he had donated $25,000 to the Republican National Committee.[10]

In addition to his business and political interests, he was known in the area as a donor to a range of educational institutions.[11] He also figured in the creation of the Capital Crescent Trail; having purchased the DC portion of the newly abandoned Georgetown branch from CSX in 1989, he sold the route to the National Park Service the following year.[12] In his retirement, Gould was known in the Baltimore-area as a donor to a range of educational institutions.[11] Gould died on January 16, 2018, at his home in North Laurel, Maryland of pneumonia at the age of 94, 13 days after his 94th birthday.[2]

References

edit- ^ Nixon= the fifth year of his presidency. Congressional Quarterly. 1974. ISBN 9780871870520. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kingdon Gould Jr., Former Ambassador And Horseman, Dies At 94". The Baltimore Sun. January 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Glaros, Tony (June 10, 2014). "Developer Kingdon Gould Jr. reflects on his 60-year legacy". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Renehan Jr., Edward J. (2005). Dark Genius of Wall Street: The Misunderstood Life of Jay Gould, King of the Robber Barons. Basic Books. pp. 310–311.

- ^ Mosk, Matthew (September 26, 2006). "Highway Backer a Steady Ehrlich Donor". Washington Post. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ "Kingdon Gould Jr. is the grandfather of US olympian Georgia Gould". Georgia Gould.com. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ "Chiefs of Mission by Country, 1778–2005: Luxembourg". United States Department of State. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Chiefs of Mission by Country, 1778–2005: Netherlands". United States Department of State. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Description". Baltimore Council on Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on December 13, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ Giroux, Greg (October 23, 2006). "RNC Money Flowing to Key Races in Battle for Congress". New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ a b "Glenelg Country School: History". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Milestones: 1986-1996" (PDF). Coalition for the Capital Crescent Trail. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2007.