This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

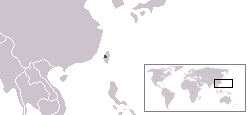

The Kingdom of Middag (Chinese: 米達赫王國; pinyin: Mǐdáhè Wángguó; Wade–Giles: Mi³-Ta²-Hê⁴ Wang²-kuo²), also known as the Kingdom of Dadu (Chinese: 大肚王國; pinyin: Dàdù Wángguó; Wade–Giles: Ta⁴-tu⁴ Wang²-kuo²), was a supra-tribal alliance located in the central-western plains of Taiwan in the 17th century. This polity was established by the Taiwanese indigenous peoples of Papora, Babuza, Pazeh, and Hoanya.[citation needed] It ruled as many as 27 villages, occupying the western part of present-day Taichung county and the northern part of modern Changhua county.[1] Having survived the rule of European colonists and the Kingdom of Tungning, the aboriginal peoples who previously comprised Middag were eventually subjugated to the rule of the Qing Empire in the 18th century.

Kingdom of Middag | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ?–17th century | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Middag | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Various Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• ?–1648 | Kamachat Aslamie | ||||||||||

• 1648–? | Kamachat Maloe | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Discovery | ||||||||||

• Established | ? | ||||||||||

• Suppressed by Dutch | 17th century | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||

Names

editThe Kingdom of Middag is a western name for the political entity. In Taiwan, it is known as the Kingdom of Dadu (Chinese: 大肚王國; pinyin: Dàdù Wángguó; Wade–Giles: Ta-tu Wang-kuo; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tōa-tō͘ Ông-kok), Dadu being the modern-day name of the historical capital Middag.

The 17th-century leader Kamachat Aslamie was known in Hoklo as Quata Ong (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Khoa-ta Ông), and sometimes in Dutch as Keizer van Middag.[1] (This means "Emperor of Midday" in Dutch, "middag" being the Dutch word for afternoon.) The most common aboriginal name was Lelian ("Sun King").

History

editThe kingdom first came into contact with the West after the Dutch East India Company established its Government of Formosa in 1624. David Wright, a Scottish agent of the Company who lived on the island in the 1640s, listed Middag among 11 "shires or provinces" of the plains region, described as follows:

"The third dominion belongs to the king of Middag, and lies against the north-east of Tayouan, southward of the river Patientia. This prince has seventeen towns that obey him, the largest being called Middag, which is also his chief seat and place of residence. Sada, Beodor, Deredonesel, and Goema, are four other of his eminent towns, the last-named being a handsome place, and situated on a plain five miles from Patientia, whereas the others are built on hills. The king of Middag had formerly twenty-seven towns under his jurisdiction, but ten of them threw off his yoke. He keeps up no great state, and has only one or two attendants accompanying him when going abroad. He would never suffer any Christians to dwell in his dominions, allowing them only to travel through it."[2]

After the Dutch conquered the Spanish colony in northern Taiwan in 1642, they sought to establish control of the western plains between the new possessions and their base at Tayouan (modern Tainan). After a brief but destructive campaign, Pieter Boon was able to subdue the tribes in this area in 1645. Kamachat Aslamie, a ruler of Middag, was given a cane as a symbol of his local rule under Dutch overlordship. Between 1646 and 1650, the Company divided his lands into six parts and leased them to Chinese farmers.[1][3] During this period, Kamachat Aslamie died and was succeeded by his nephew Kamachat Maloe, but his successor was never referred to by the title Quata Ong.[1]

In 1662, the Ming loyalist Koxinga and his followers laid siege to the Dutch outpost and eventually established the Kingdom of Tungning. Under the terms of the surrender, Koxinga took over all the Dutch leases. On a constant war footing and denied maritime trade by the hostile Dutch-Qing alliance, the Kingdom of Tungning intensively exploited these lands to feed their vast army. This resulted in a number of brutally suppressed rebellions by the indigenous population and a gradual weakening of Middag.[1]

Qing rule

editAfter the successful Qing campaign that resulted in the capitulation of the Kingdom of Tungning, transportation between Taiwan and mainland China was restored, and the immigration of the ethnic Han population to the island—albeit discouraged by official edicts—resurged. Aboriginal peoples faced even greater pressure from the exponentially growing Han population seeking to "open" more farmlands on the island.

Due to the lack of historical records and archaeological evidence, the actual lineage and developments of the kingdom cannot be ascertained. According to the accounts by Huang Shujing, a Qing official dispatched to Taiwan in the early 18th century, and a supra-tribal leadership remained in existence in the Dadu area at that time. However, during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor later in that century, the population in the traditional Middag territories rose to oppose heavy labor imposed by the Qing authorities and was brutally quelled by Qing troops and collaborative indigenous communities in 1732, a year after the initial uprising. After this turmoil came to an end, a supra-tribal leadership apparently ceased to exist in the island's central-western plains. In the aftermath of this, the descendants of Middag either fused into the majority Han population through intermarriage or migrated to present-day Puli, a basin township surrounded by high mountains in central Taiwan.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Wang, Hsing'an (2009). "Quataong". Encyclopedia of Taiwan.

- ^ *Valentijn, François (1903) [First published 1724 in Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën]. "Notes on the Topography". In Campbell, William (ed.). Formosa under the Dutch: described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. London: Kegan Paul. p. 6. ISBN 9789576380839. LCCN 04007338.

- ^ Chiu, Hsin-hui (2008). The Colonial 'Civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa, 1624–1662. BRILL. pp. 99–102. ISBN 978-90-0416507-6.