40°43′18″N 112°11′53″W / 40.721563°N 112.198118°W

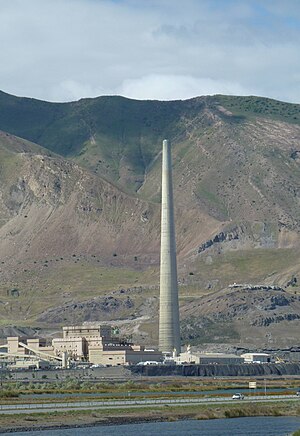

Kennecott Utah Copper LLC’s Garfield Smelter Stack is a 1,215-foot (370 m) high smokestack west of Magna, Utah, alongside Interstate 80 near the Great Salt Lake. It was built to disperse exhaust gases from the Kennecott Utah Copper smelter at Garfield, Utah.[1] It is the 60th-tallest freestanding structure in the world, the 4th-tallest chimney, and the tallest man-made structure west of the Mississippi River.

Waste gases

editThe Garfield Smelter Stack was completed in 1974, replacing several earlier smokestacks, the tallest of which was 413 feet (126 m) high. The extra height was needed to meet the requirements of the Clean Air Act of 1970, to disperse waste gases according to new standards.[1]

In response to new emissions limits and anticipated future state and federal standards, Outokumpu and Kennecott had conducted flash converting pilot tests from 1985 at Outokumpu's research facility in Finland. With the introduction of strict new environmental regulations in the state of Utah, the smelter's maximum permissible sulfur emission was decreased to 1,082 short tons (982 t) per year from the earlier 18,574 short tons (16,850 t). In 1995 a new, cleaner flash smelting furnace was commissioned. By 2004, the annual average SO2 emissions from the stack were 161.5 lb/h (73 kg/h), below the permitted average annual level of 211 lb/h (96 kg/h) (with a three-hour permitted SO2 limit of 552 lb/h (250 kg/h)).[2][3][4]

The off-gases from the flash smelting furnace contain 35–40% sulfur dioxide. They are cooled and cleaned in a waste-heat boiler, electrostatic precipitator and scrubbing system before being sent to the sulfuric acid plant. The acid plant produces either 94% or 98% sulfuric acid with tail gas containing typically 50–70 ppm sulfur dioxide, resulting in a measured sulfur fixation of greater than 99.9%. In 2006, the company produced and sold approximately 833,000 short tons (756,000 t) of sulfuric acid, made from the formerly released gas. The acid recovery plant is designed to also recover waste heat from the process to produce electrical power. Approximately 24 MW of electrical power is generated, representing 70% of the smelter’s electrical requirements.[5][6]

Design and construction

editThe stack is 177 feet (54 m) in diameter at the bottom with 12-foot (3.7 m) walls, and rises directly from the ground. At the top it is 40 feet (12 m) in diameter and 12 inches (0.30 m) thick. A large fiberglass duct passes up the stack and carries gases to the top.[1][7]

26,317 cubic yards (20,121 m3) of wood and 900 short tons (820 t) of steel were used in its construction. Construction commenced on August 26, 1974 and finished on November 19, an 84-day concrete pour. It cost $16.3 million at the time to build,[1][7] equivalent to $101 million in 2023.

The top can be accessed by a Swedish-built elevator that crawls up a gear track on the inside surface. It takes 20 minutes to ascend the stack, although workers only need to travel up to the 300-foot level each day, to service the air-sampling station.[1]

The Garfield Smelter Stack is the tallest free-standing structure west of the Mississippi River, the fourth tallest smokestack in the world and the fifty-ninth tallest free-standing structure on earth. It is approximately as tall as the Berlin TV Tower, the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, or the Bank of America Tower in New York City. It is the only operating smelter chimney left in Utah.[6][1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Arave, Lynn (November 16, 2009). "Holy smokes: Kennecott smelter, Utah's tallest man-made structure, to turn 35". Deseret News. Archived from the original on December 20, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ "Sustainable Development Report" (PDF). Kennecott Utah Copper. Rio Tinto. 2004. p. 44. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ "A Big Step for Copper Smelting: Flash Converting". Outokumpu News. Copper Development Association Inc. February 1998. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Pipkin, Bernard W.; Trent, Dee; Hazlett, Richard; Bierman, Paul (2013). "Mineral Resources and Society". Geology and the Environment. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning, National Geographic Society. p. 478. ISBN 9781133603986. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Sulfuric Acid Environmental Profile Life Cycle Assessment" (PDF). Kennecott. Kennecott Utah Copper, LLC. 2006. p. 2. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Newman, C.J.; Collins, D.N.; Weddick, A.J. (1999). "Recent Operation and Environmental Control in the Kennecott Smelter". In Diaz, C.; Landolt, C.; Utigard, T. (eds.). Copper 99-Cobre 99: Smelting Technology Development, Process Modeling and Fundamentals (PDF). Warrendale, PA: Minerals, Metals, and Materials Society. p. 29. ISBN 9780873394406. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Quick Facts about Kennecott Utah Copper's Garfield Smelter Stack" (PDF). Kennecott Utah Copper. Rio Tinto. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

Further reading

edit- (1994) "Copper Mining" article in the Utah History Encyclopedia. The article was written by Philip F. Notarianni and the Encyclopedia was published by the University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874804256. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022, and retrieved on October 2, 2024.

External links

edit- Kennecott Utah Copper

- A comparison with other large stacks of the world can be seen at skyscraperpage