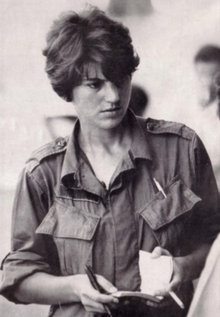

Kate Webb (24 March 1943 – 13 May 2007) was a New Zealand-born Australian war correspondent for UPI and Agence France-Presse. She earned a reputation for dogged and fearless reporting throughout the Vietnam War, and at one point she was held prisoner for weeks by North Vietnamese troops. After the war, she continued to report from global hotspots including Iraq during the Gulf War.

Kate Webb | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Catherine Merrial Webb 24 March 1943 |

| Died | 13 May 2007 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | New Zealander and Australian |

| Other names | Highpockets |

| Occupation | War correspondent |

| Known for | Held prisoner while reporting on Vietnam War |

| Honours | Kate Webb Prize, and depicted on a $1 stamp |

Biography

editBorn Catherine Merrial Webb in Christchurch, New Zealand, Webb moved to Canberra, Australia, with her family while she was still a child. Her father, Leicester Chisholm Webb, was professor of political science at the Australian National University,[1] and her mother, Caroline Webb, was active in women's organisations.[2]

On 30 March 1958, at the age of 15, Catherine Webb was charged with the murder of Victoria Fenner, the adopted daughter of Frank Fenner, in Canberra. She supplied a rifle and bullets to Fenner and was present when Fenner shot herself in what was intended as a Suicide pact. After a Children's Court hearing the charge was dropped.[3]

Her parents were killed in a car accident in Tasmania when she was 18.[4]

She graduated from the University of Melbourne, then left to work for the Sydney Daily Mirror. In 1967, she quit the paper and travelled to South Vietnam to cover the escalating war. She applied to join UPI, but the Saigon bureau chief rejected her saying "What the hell would I want a girl for?". She then worked for local South Vietnamese newspapers until Ann Bryan the editor of Overseas Weekly gave her assignments and arranged her MACV press accreditation allowing her to cover U.S. military operations.[5]: 135–6 She began receiving assignments from UPI and as a non-U.S. passport holder and French speaker was assigned to report on Jacqueline Kennedy's visit to Cambodia in November 1967.[5]: 136–7

She was the first wire service reporter to reach the U.S. Embassy in Saigon during the Tet offensive.[6] Her reporting of the Embassy attack led to her being employed full-time by UPI, initially as a gofer for Dan Southerland.[5]: 137 Webb earned a reputation as a hard-drinking, chain-smoking war correspondent.[7]

In 1969, she began a relationship with a Green Beret officer and in late 1969, she accepted his marriage proposal, resigned from UPI and moved with him to Fort Bragg at the end of this tour in South Vietnam. On her arrival at Fort Bragg, she learned that her fiancé was already married and despite claiming that he would divorce his wife, soon decided to stay with her. Webb received work from UPI in Pittsburgh staying there into early 1970. In early May, she covered the Kent State shootings for UPI. Two weeks later, she was appointed to be deputy bureau chief in the newly established UPI bureau in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.[5]: 154–8 She moved into the Hotel Le Royal.[5]: 170

Following the killing of Phnom Penh bureau chief Frank Frosch on 28 October 1970, while covering Operation Chenla I, Webb was selected to fill his position; she later claimed it was because she spoke French.[6]

In early 1971, she broke the story that Cambodian premier Lon Nol had suffered a stroke and was partially paralyzed, a story that was being kept secret by the Khmer Republic government.[5]: 184

On 7 April 1971, she made news herself when she, a Japanese photojournalist Toshiichi Suzuki and Cambodian journalists Tea Kim Heang, Chhim Sarath, Vorn and Charoon were captured by People's Army of Vietnam troops fighting Khmer National Armed Forces in an operation on Highway 4.[5]: 189 On 20 April, official reports claimed that a body discovered was Webb's, and The New York Times and other newspapers published obituaries for her.[8] On 1 May Webb and the others were released by the PAVN near where they had been captured, after having endured forced marches, interrogations, and malaria.[5]: 190–7 She described her experiences in a book called On the Other Side published in 1972.

After her release from captivity, she flew to Hong Kong to be treated for malaria and wrote a series of stories about her captivity.[5]: 199 After 20 days in Hong Kong, she then flew back to Australia to recuperate but was met by a media frenzy.[5]: 200 Given her sudden fame, UPI sent her to Washington DC as their show piece. On her arrival in New York, colleagues became concerned about her health and she was diagnosed with cerebral malaria and put into a medically induced coma. Following her recovery, she insisted on returning to Cambodia arriving in mid-1971; however, her nerves were shattered and UPI posted her to Hong Kong in early 1972.[5]: 201–2 Soon thereafter, she threatened to resign if she did not get a "real job". She was reassigned to the Philippines as the UPI bureau chief in Manila. She briefly returned to Phnom Penh in July 1973, reporting on the effects of continued U.S. bombing on the country.[5]: 219–22

As Cambodia and South Vietnam were falling to Khmer Rouge and PAVN offensives in April 1975, she requested that UPI send her back into the war zone, but instead she was sent to Clark Air Base which was used to support the evacuations of Phnom Penh and Saigon. She was then reassigned to the USS Blue Ridge the United States Seventh Fleet flagship and command ship for the Saigon evacuation.[5]: 232–5

After the war, she continued to work as a foreign correspondent for UPI based in Singapore, but quit after being sexually harassed by her boss. She then moved to Jakarta where she worked in public relations for a hotel and began a long-term relationship with John Stearman, an American oil engineer.[5]: 242

She returned to journalism in 1985 joining Agence France-Presse (AFP) serving as a correspondent in Iraq during the Gulf War, in Indonesia as Timor-Leste gained independence, and in South Korea, where she was the first to report the death of Kim Il Sung. She also reported from Afghanistan, and later described an incident in Kabul as the most frightening in her career. Following the collapse of Mohammad Najibullah's communist regime, she was captured by a local warlord and brought to a hotel, where she was brutally beaten and dragged up a flight of stairs by her hair.[6] She finally escaped with the help of two fellow journalists, and hid out on a window ledge in the freezing Afghan winter, while the warlord and his men searched the building for her.[7] She returned to Cambodia in 1993 and made her final visit to Vietnam in 2000.[5]: 243

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Panel discussion featuring Webb on War Torn, September 24, 2002, C-SPAN |

Webb retired to the Hunter Region in 2001. She wrote an essay for War Torn, a collection of reminiscences by women correspondents in the Vietnam War and taught journalism for a year Ohio University. She died of bowel cancer on 13 May 2007. In 2008, AFP established the Kate Webb Prize, worth €3,000 to €5,000, awarded annually to an Asian correspondent or agency that best exemplified the spirit of Kate Webb.[9] Webb was commemorated on an Australian postage stamp in 2017.[10][5]: 243–4

She is survived by a brother, Jeremy Webb, and a sister, Rachel Miller.

References

edit- ^ John Warhurst, "Webb, Leicester Chisholm (1905–1962)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16, (MUP), 2002. Via ADB Online.

- ^ For example Caroline's article in The Press, September, 1942, cited in Official History of New Zealand, chapter 21, "Women at War".

- ^ "Suicide Finding Death of Girl 15 In Canberra", Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1958, p. 3.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (15 May 2007). "Kate Webb, 64; pioneering UPI foreign correspondent was captured in Vietnam War". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Becker, Elizabeth (2021). You Don't Belong Here How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War. Public Affairs Books. ISBN 9781541768208.

- ^ a b c "Kate Webb, 64; pioneering UPI foreign correspondent was captured in Vietnam War", The Los Angeles Times, 15 May 2007.

- ^ a b "Kate Webb: Veteran war reporter held captive in the Cambodian jungle", The Independent, 15 May 2007.

- ^ 'A Masked Toughness', The New York Times, 21 April 1971.

- ^ "AFP Kate Webb Prize". Facebook.

- ^ "AFP journalist Kate Webb featured on Australian stamp". AFP.com. Agence France-Presse. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

External links

edit- "Fearless reporter in search of truth", Obituary, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 2007