The Judicial Papyrus of Turin (also Turin legal papyrus) is a 12th-century BCE ancient Egyptian record of the trials held against conspirators plotting to assassinate Ramesses III in what is referred to as the "Harem conspiracy". The papyrus contains mostly summaries of the accusations, convictions and punishments meted out.[2]

| Judicial Papyrus of Turin | |

|---|---|

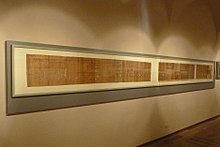

Judicial Papyrus displayed in the Museo Egizio, Turin | |

| Material | Papyrus |

| Writing | Hieratic Egyptian |

| Created | 20th Dynasty c. 1190-1077 BCE[1] |

| Discovered | before 1824[1] Egypt |

| Present location | Turin, Italy |

The Judicial Papyrus is the largest and most complete of a series of documents that refer to the conspiracy. The others, Papyrus Rollin, Papyrus Varzy, Papyrus Lee, Papyrus Rifaud I and II, may once have been part of the same document as the portion in Turin. The text seems to have been separated by a thief who carefully cut the document, making sure to not do much damage to the text itself.[3] The Rollin and Lee papyri provide further details of the case, highlighting the condensed nature of the Judicial Papyrus.[4] The document contains the entire list of those who participated in the conspiracy, as well as their verdict and punishment they received.[5]

Historical background

editThe reign of Ramesses III was characterized by external conflict and internal decline, which seem to have weakened the position of the pharaoh, surrounded by servants and officials of foreign descent. Symptomatic for the state of the country was the apparent incapability of the bureaucracy to supply the workers at Deir el-Medina which brought about the first recorded strike in history in the 29th year of Ramesses' reign.[6] In this atmosphere of uncertainty, Queen Tiye[Note 1] wanted to substitute her own son Pentawer for Ramesses' designated heir, the future Ramesses IV, a son of another wife, Tyti[9] and she had no problems finding influential people who would assist her.

The conspiracy

editTiye enlisted the help of Pebekkamen, a pantry chief, Mastesuria, a butler, Panhayboni, a cattle overseer, Panouk, overseer of the harem, and Pendua, a clerk of the harem. This group were responsible for attempting to raise a rebellion against the king, with Pebekkamen disseminating the call to action:

...he had begun to bring out their word to their mothers and their brothers who were there, saying: 'Stir up the people! Incite enmity in order to make rebellion against their lord!'[10]

During the Beautiful Festival of the Valley the plotters assassinated Ramesses III, but failed to place Pentawer on the throne. The conspirators were arrested and put on trial.

The trial

editThe papyrus is not a detailed record of court proceedings, but rather a list of the defendants, who were often referred to by a pseudonym such as Mesedsure, meaning "Re hates him",[11] the crimes they were accused of and their sentences.

It was once thought that Ramesses III survived the initial attack, only to die some time later. This is due in part to the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, which preserves a record of the trials of the conspirators, being carried out under his name. The document opens with:

[King Usermare'-Meriamun, l.p.h., Son of Re': Ramesses] Ruler of Heliopolis [l.p.h. said]... I commissioned the overseer of the treasury Montemtowe; the overseer of the treasury Pefrowe; the standard-bearer Kara; the butler Paibese, the butler Kedendenna; the butler Ba'almahar; the butler Peirswene; the butler Dhutrekhnefer; the king's adjutant Penernute; the clerk Mai; the clerk of the archives Pre'em-hab; the standard-bearer of the infantry Hori; saying 'As for the matters which the people-I do not know who-have plotted, go and examine them'.[12]

After giving the instructions to the judges, he then reports the following outcomes:

And they went and examined them, and they caused to die by their own hands those whom they caused (so) to die, though [I] do not know [wh]o, [and they] also punished [the] others, though I do not know who. But [I] had charged [them strictly], saying: 'Take heed, have a care lest you allow that [somebody] be punished (9) wrongfully [by an official] who is not over him'.[12]

It is now known that Ramesses III did not survive the attempt on his life, and that the trial was carried out by his successor Ramesses IV in the name of his murdered father.[13]

The court consisted of twelve judges: Montemtowe and Pefrowe, overseers of the treasury; Kara and Hori, standard-bearers; Paibese, Kedendenna, Ba'almahar, Peirswene, and Dhutrekhnefer, butlers; Penernute, the king's adjudant; and Mai and Pre'em-hab, clerks. Over the course of three trials, those who actively participated in the conspiracy and those who aided them were tried before the court, found guilty and punished accordingly. Pebekkamen, Mastesuria, Panayboni, Panouk, and Pedua were all

placed before the officials of the Court of Examination; they found him guilty; they caused his punishment to overtake him.[13]

In total, 28 people were executed while 10, including Pentawer, were allowed to take their own lives. The text refers to it laconically as:

They (i.e. the judges) left him in his where he was, he took his own life.[13]

The fourth and fifth trials concern the punishment of members of the court. A further four people, including two of the judges, Paibese and Mai, had their noses and ears cut off, and another was verbally reprimanded, for cavorting with the accused women. Hori was also involved but his punishment is not recorded.[13]

Aftermath

editIt had been thought that Ramesses III lived long enough to oversee the trial of his attempted assassins as the document opens with him addressing the judges directly. However, he is referred to in the Papyrus Lee as "the Great God", a term used only for deceased kings at this time.[14] His well-preserved and still wrapped mummy does not display any outward signs of a violent death so the cause of death was long assumed to be a natural one.[15] Recent CT scanning revealed that beneath the bandages on his neck was a large gash that cut all the way to the bone. This injury proved fatal.[16][17]

The mummy of 'Unknown Man E' has been confirmed as a son of Ramesses III. This mummy was not mummified in a typical fashion, and was interred in a ritually impure goatskin inside an uninscribed coffin. This treatment certainly makes the body a likely candidate for that of Pentawer.[16]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Cat.1875". Papyri Museo Egizio. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Vernus (2003), pp. 108f

- ^ Redford, Susan (2002). The Harem Conspiracy : the murder of Ramesses III. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-87580-295-4.

- ^ Goedicke, Hans (December 1963). "Was Magic Used in the Harem Conspiracy against Ramesses III? (P.Rollin and P.Lee)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 49: 71–92. doi:10.2307/3855702. JSTOR 3855702.

- ^ de Buck, A. (1937). "The Judicial Papyrus of Turin". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 23 (2). Egyptian Exploration Society: 152–164. doi:10.2307/3854420. JSTOR 3854420.

- ^ Edwards (2000), p. 246

- ^ cf. Edwards (2000), p. 246

- ^ Breasted (1906), p. 208

- ^ Collier, Mark; Dodson, Aidan; Hamernik, Gottfried (2010). "P. BM EA 10052, Anthony Harris, and Queen Tyti". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 96: 242–247. doi:10.1177/030751331009600119. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 23269772. S2CID 161861581.

- ^ de Buck, A. (December 1937). "The Judicial Papyrus of Turin". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 23 (2): 153–154. doi:10.2307/3854420. JSTOR 3854420.

- ^ Montet (1981), p. 217

- ^ a b de Buck, A. (December 1937). "The Judicial Papyrus of Turin". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 23 (2): 154. doi:10.2307/3854420. JSTOR 3854420.

- ^ a b c d de Buck, A. (December 1937). "The Judicial Papyrus of Turin". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 23 (2): 152–164. doi:10.2307/3854420. JSTOR 3854420.

- ^ Breasted (1906), §418

- ^ Harris, James E.; Weeks, Kent R. (1973). X-Raying the Pharaohs (Hardback ed.). London: Macdonald and Company (Publishers) Ltd. p. 163. ISBN 0356043703.

- ^ a b Hawass, Zahi; Ismail, Somaia; et al. (December 17, 2012). "Revisiting the harem conspiracy and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study". BMJ. 345. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: e8268. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8268. hdl:10072/62081. PMID 23247979. S2CID 206896841. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar N. (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs : CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies (Hardback ed.). New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-977-416-673-0.

Bibliography

edit- Breasted, James Henry (1906). The Twentieth to the Twenty-Sixth Dynasties. Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. IV. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Edwards, I. E. S., ed. (2000). Cambridge Ancient History, Part 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Montet, Pierre (1981). Everyday Life in Egypt in the Days of Ramesses the Great. Translated by A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop; Margaret S. Drower. Introduction by David B. O'Connor. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1113-9.

- Vernus, Pascal (2003). Affairs and Scandals in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4078-6.

Further reading

edit- Watterson, Barbara (1997). The Egyptians. The Peoples of Africa. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-21195-2.