John W. Lindsey was a slave trader based in Montgomery, Alabama, United States in the 1840s and 1850s.

John W. Lindsey | |

|---|---|

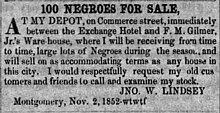

"100 Negroes for Sale" The Weekly Advertiser, June 8, 1853 | |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

Biography

editFrederic Bancroft described the nature of the Montgomery slave market in his 1931 history Slave-Trading in the Old South:

Montgomery, the capital of Alabama and a good shipping-point, attracted politicians, planters and much general business, although in 1860 its total population was less than 9,000, of whom more than half were slaves and 102 were free colored. Its slave-trade was patronized chiefly by the central part of the State, for northern Alabama drew supplies from markets in other States, and Montgomery traders had competitors in Columbus, Georgia, on the east, Selma on the west, and Mobile on the southwest. Yet the capital did a thriving trade in slaves. The City Directory for 1859 listed four 'slave depots' along with the same number of banking establishments, whereas for the joyful visitors to the first capital of the Confederacy in February, 1861, there were only four regular hotels.[1]

According to the 1950 history Slavery in Alabama, the records of the Montgomery County probate court clearly reveal the names of the major slave traders working in the city, as they would return year after year to harvest unwanted slaves from the estates of the dead and carry them off to be resold.[2] The names of traders and trading firms that recurred most frequently in records dating from 1838 to 1860 were Hill & Hartwell, Williamson & Puryear, Brown & Watson, Mason Harwell, and Lindsey.[2]

A runaway slave ad placed by H. M. Waters of Coffee County, Alabama in 1851 sought the return, for a reward of $30, of his slaves Joe and Adeline, about whom he wrote, "Joe is about 6 feet 8 inches high, and about 35 years of age, rather a bright colored negro, and has had the small pox. Adeline is of medium size, black, and has a downcast look when spoken to, and is about 32 years of age. I purchased the above negroes from Lindsey, a negro trader in Montgomery. They may possibly be making for that place or Prairie Bluff on the Alabama river."[3]

Lindsey advertised his business in the newspaper throughout 1852 and 1853, and one of the "100 Negroes for Sale" ads caught the attention of Harriet Beecher Stowe, who included it in her non-fiction polemic, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. She reprinted it, with the commentary, "Mr. Lindsey is going to be receiving, from time to time, all the season, and will sell as cheap as anybody; so there's no fear of the supply falling off...Query: Are these Messrs. Sanders & Foster, and J. W. Lindsey, and S. N. Brown, and McLean, and Woodroof, and McLendon, all members of the church, in good and regular standing? Does the question shock you? Why so? Why should they not be? The Rev. Dr. Smylie, of Mississippi, in a document endorsed by two Presbyteries, says distinctly that the Bible gives a right to buy and sell slaves." [4]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Bancroft (2023), p. 294.

- ^ a b Sellers (2015), p. 155.

- ^ "Thirty Dollars Reward". The Weekly Advertiser. July 2, 1851. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- ^ Stowe (1853), p. 339–344.

Sources

edit- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- Sellers, James Benson (2015) [1950]. "Chapter 5: Traffic in Slaves". Slavery in Alabama. Library of Alabama Classics. Introduction by Harriet E. Amos Doss. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817389147. LCCN 50004433. OCLC 899157440.

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.