John Husee (died November 1548) (alias Hussey) was a London merchant, and the business agent in England of Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d.1542), during Lisle's absence abroad whilst serving as Governor of Calais during the years 1533 to 1540. Lord Lisle's correspondence was seized by the state when he was arrested in May 1540 for treason and heresy, and as a result, 515 letters written by Husee between 1533 and 1540 to Lord and Lady Lisle survive, mainly now preserved amongst the State Papers held at the National Archives.[2] They were transcribed into modern English and in 1981 published, together with all the other Lisle Papers, by Muriel St Clare Byrne in her six-volume work "The Lisle Letters".

John Husee | |

|---|---|

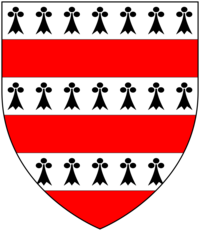

Arms of Husee (or Hussey): Barry of six ermine and gules[1] | |

| Died | November 1548 Calais |

| Father | John Husee |

| Mother | Elizabeth Holt |

Origins

editHusee was the son of John Husee, a Southampton merchant, by his wife Elizabeth Holt, a daughter and co-heiress of John Holt of Hampshire. He had a brother who lived in London, but otherwise little is known of his family.[3]

Husee the elder traded principally in wine, and in 1500 he and several of his fellow merchants in Southampton were accused of corruption in the handling of the customs. The damage to his career was not lasting. He served as Sheriff of Southampton for a term in 1511–12. Shortly thereafter he moved to London, where in January 1516 he was admitted to the Worshipful Company of Vintners, and by November 1517 was one of the junior wardens of the company. In 1525 he was elected as one of the Chamberlains of the City of London. In 1528 he became Master of the Vintners. He was living in 1539, but nothing further is known of him.[3]

Husee hearse-cloth

editA magnificent embroidered hearse-cloth (or coffin cover) given by John Husee senior to the Vintners Company on 14 February 1539[4] is still held by the company. It was used to cover the coffins of deceased prominent members, and was used for that purpose until 1931. It is made from gold and purple cloth and is decorated with biblical scenes, with vines and the arms of Husee (Barry of six ermine and gules) and the Vintner's Company (Sable, a chevron between three wine-tuns argent) in alternate corners.[5] St Martin, the Patron Saint of Vintners, is shown at each end, dividing his cloak with the beggar and as Bishop of Tours giving alms to a cripple. On the long sides are shown various images of Death personified as a skeleton holding a coffin.[6] His armorials are shown on the hearse-cloth as Barry of six ermine and gules, which are the arms of the ancient family of Husee established at Harting in Sussex in the 12th century.[7]

Career

editHusee began his career as his father's apprentice in 1520, and was admitted as a freeman of the Vintners in June 1527. In February of that year he obtained royal letters of protection, and joined the retinue of the Governor of Calais, Sir Robert Wingfield.[3]

In August 1533 Husee entered the service of the newly appointed Lord Deputy of Calais, Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle, an illegitimate son of Edward IV, and in his youth a close companion of Henry VIII.[3][8] As Grummitt puts it, Husee 'quickly became Lisle's indispensable right-hand man', and 'the consummate Tudor servant'. He carried letters from Calais to England, and kept Lord Lisle informed of political events at court. Much of his time, particularly in the 1530s, was spent in England following Lord Lisle's suits at law. Husee was particularly adept at relations with those in the upper echelons of power, and even at times offered Lord Lisle advice on dealing with King Henry VIII, who evidently liked him.[3]

Husee performed more mundane tasks for the Lord Deputy and his family as well, seeing to the care of Lady Lisle's children by her first marriage when they were in England, finding suitable servants, and purchasing goods in London.[3]

Husee was compensated for his services with a post in the Calais garrison which by 1535 provided him with a daily wage of 8d. In October 1536 he received a grant for life from the Crown as 'searcher of the lordships of Marke and Oye within the Calais pale', which brought him an additional 8d a day.[3]

The holding of the office of Lord Deputy entailed considerable expense, and Lisle wished to give up the post and return to England. Husee made frequent overtures to Cromwell to obtain funds to cover Lisle's expenses, and to obtain leave for Lisle and his family to return home. However, according to Grummitt, Cromwell would not agree until he had secured for himself Lisle's manor of Painswick in Gloucestershire. Lisle conveyed the manor to Cromwell in 1539, who sold it the following year to Sir William Kingston and his wife, Mary.[3][8][9]

Husee's service to the Lisles was brought to an end by Lord Lisle's arrest on treason charges on 19 May 1540. Lisle was accused of communicating with Cardinal Reginald Pole, and spent the next two years in the Tower of London.[8] After his master's ruin, Husee continued to hold his position in the Calais garrison, and in that capacity took part in 1544 in the English siege of Boulogne.[3]

Little is known of Husee's private life. There is no evidence that he married. He died at Calais in November 1548.[3]

The Lisle Papers are held by the National Archives.[10] They were published as the Lisle Letters in 1981. Husee is 'the most fully documented of all the writers of this correspondence. His letters are a joy and a revelation to read. He was completely loyal to the Lisles, a friend as much as an agent, and a very wise one in the appalling world of the Tudor court'.[11]

Notes

edit- ^ Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, p. 352

- ^ Byrne, 1981, vol.1, p. 351: 398 in the 18 volumes of the "Lisle Papers" (held at the National Archives under SP.3, mainly in vols. 4,5,11 & 12; 116 in the State Papers of Henry VIII (SP.1); 1 uncalendared letter amongst the Cottonian Manuscripts at the British Museum (Byrne, vol.1, p. 102, note 1))

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Grummitt 2006.

- ^ Byrne, vol.1, p. 354: 1539; Vintner's Company website

- ^ Byrne, vol.1, p. 354

- ^ [1]; At the Vintners’ Hall, 24 February 2012 Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, p. 352. Date of gift of hearse-cloth stated by Byrne as 1539

- ^ a b c Grummitt 2004.

- ^ 'Painswick: Manors and other estates', A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 11: Bisley and Longtree Hundreds (1976), pp. 65–70 Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Lisle Papers, National Archives Retrieved 27 June 2103.

- ^ Plumb, J.H., 'Henry VIII Was The Man To See', New York Times, 14 June 1981 Retrieved 27 June 2013.

References

edit- Byrne, M. St. Clare; Boland, Bridget (1983). The Lisle Letters; An Abridgement. Chicago: Chicago University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780226088006. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- Grummitt, David (2006). "Husee, John (d. 1548)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/74945. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Grummitt, David (2004). "Plantagenet, Arthur, Viscount Lisle (b. before 1472, d. 1542)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22355. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

edit- Kathy Lynn Emerson, 'Delicious Details From Letters To Ladies' Retrieved 27 June 2013