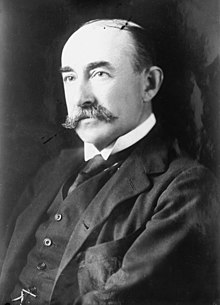

John Hays Hammond (March 31, 1855 – June 8, 1936) was an American mining engineer, diplomat, and philanthropist. He amassed a sizable fortune before the age of 40. An early advocate of deep mining, Hammond was given complete charge of Cecil Rhodes' mines in South Africa and made each undertaking a financial success. He was a main force planning and executing the Jameson Raid in 1895. It was a fiasco and Hammond, along with the other leaders of the Johannesburg Reform Committee, was arrested and sentenced to death. The Reform Committee leaders were released after paying large fines, but like many of the leaders, Hammond escaped Africa for good. He returned to the United States, became a close friend of President William Howard Taft, and was appointed a special ambassador. At the same time, he continued to develop mines in Mexico and California and, in 1923, he made another fortune while drilling for oil with the Burnham Exploration Company.

John Hays Hammond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 31, 1855 |

| Died | June 8, 1936 (aged 81) |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York, US |

| Alma mater | Yale University (Ph.B., 1876) |

| Occupation(s) | mining engineer, diplomat |

| Spouse(s) | Natalie Harris (January 1, 1881 – June 18, 1931) |

| Children | John Hays Hammond, Jr. (April 13, 1888 – February 12, 1965) Natalie Hays Hammond (January 6, 1904 – June 30, 1985) Nathaniel Harris Hammond (1902–1907) Richard Pindle Hammond (August 26, 1896 – December 2, 1980 Harris Hays Hammond (November 27, 1881 – August 9, 1969) |

| Parent(s) | Sarah (Hays) Lea Richard Pindell Hammond |

Early life

editHammond was the son of Major Richard Pindell Hammond, a West Point graduate who fought in the Mexican War, and Sarah, daughter of Harmon Hays and his wife, née Elizabeth Cage. Sarah was sister to Captain John Coffee Hays of the Texas Rangers, and had formerly been married to Calvin Lea.[1] The family moved in 1849 to California to prospect in the California gold rush, and young John was born in San Francisco. After an adventurous boyhood in the American Old West, Hammond went East to attend the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, where he earned a Bachelor of Philosophy in 1876, and later attended the Royal School of Mines, Freiberg, Germany, 1876–1879, and there he met his wife-to-be, Natalie Harris.

Mining career

editHammond took his first mining job as a special expert for the US Geological Survey 1879–1880 in Washington, DC. He returned to California in 1881 to work for Senator George Hearst, the mining magnate and father of William Randolph Hearst. In 1882, he was sent to hostile country in Mexico, near Sonora, to become superintendent of Minas Nuevas. When a revolution broke out, Hammond barricaded his family in a small house and fought off the attacking guerrillas.

From 1884 to 1893, Hammond worked in San Francisco as a consulting engineer for Union Iron Works, Central Pacific Railway and Southern Pacific Railway. In 1893, Hammond left for South Africa to investigate the gold mines in Transvaal for the Barnato Brothers. In 1894, he joined the British South Africa Company to work with Cecil Rhodes and opened mines in the Rand, in Mashonaland (territory which became Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1895, he was managing Rhodes' property in Transvaal, with headquarters at Johannesburg, South Africa. An early advocate of deep-level mining, Hammond was given complete charge of Rhodes' gold and diamond mines and made each undertaking a financial success. While working for Rhodes, he made his worldwide reputation as an engineer. He continued to work for Rhodes until 1899, but events in Africa would go on to change Hammond's life forever.

Reform Committee of Transvaal

editWhen Hammond arrived in the Transvaal, the political situation was tense. The gold rush had brought in a considerable foreign population of workers, chiefly British and American, whom the Boers referred to as "Uitlanders" (foreigners). These immigrants, manipulated by Rhodes, formed a Reform Committee headed by Colonel Frank Rhodes (brother of Cecil), Hammond, and others. They demanded a stable constitution, a fair franchise law, an independent judiciary, a better educational system, and charged that the Government under President Paul Kruger had made promises, but failed to keep them. These demands were orchestrated by Rhodes, knowing that Kruger would never accede to them, justifying subsequent intervention by the British government to protect the supposed interests of British miners, the vast majority of whom had no desire to vote or settle in the Transvaal. Civility finally collapsed when Leander Starr Jameson, the British South Africa Company's Administrator General for Matabeleland, prematurely invaded the Transvaal with 1 500 troops in the ill-fated Jameson Raid and was captured by the Boers in December 1895. Shortly thereafter, the Boer government arrested Hammond and most of members of the Reform Committee and kept them in deplorable conditions. The U.S. Senate petitioned President Kruger for clemency.

The Reform Committee case was heard in April. Hammond, Lionel Phillips, George Farrar, Frank Rhodes and Percy Fitzpatrick, all of whom had signed an incriminating document found with Jameson's raiders, were sentenced to be hanged, but Kruger commuted the sentence the next day. For the next few weeks, Hammond and the others were kept in jail under deplorable conditions. In May it was announced that they would spend 15 years in prison, but by mid-June Kruger commuted the sentences of all, Hammond and the other lesser figures each paying a £2,000 fine. The ringleaders had been shipped off to London to be dealt with by the imperial Government, paying fines of £25,000 each. All fines, amounting to some £300,000, were paid by Rhodes. Shortly hereafter, Hammond left for England.

Return to United States

editAbout 1900, the now-famous Hammond moved to the U.S. and reported on mining properties in the U.S. and Mexico. He reported on the value of the Camp Bird Mine in Colorado, pursuant to its sale in 1902. His report on Winfield Scott Stratton's Independence mine, also in Colorado, and then being floated on the London market, revealed that the ore reserves had been greatly overvalued, and burst the stock bubble. He became a professor of mining engineering at Yale University 1902–1909, and from 1903 to 1907, he was employed by Daniel Guggenheim as a highly paid general manager and consulting engineer for the Guggenheim Exploration Company (Guggenex).

Hammond's five-year contract included a $250,000 base salary and "an interest from each property that he brought in to Guggenex." He earned $1.2 million in the first year alone. He employed Pope Yeatman, his eventual successor at Guggenex, and Alfred Chester Beatty.[2]

Politics

editIn 1907, Hammond became the first president of the Rocky Mountain Club and he remained president of the club until it disbanded in 1928.[3][4] Hammond was also active in the Republican Party and he became a close friend of President William Howard Taft whom he had known since his student days at Yale.[5] In early 1908 it was announced that Hammond was a candidate for Vice-President for the Republican party, but he did not receive many delegates at the national convention.[5] Nevertheless, he became acquainted with many prominent politicians at the convention and became the president of the League of Republican Clubs.[5] He moved to Washington to be closer to the President and he accompanied President Taft on many excursions.[5] In 1911, Taft then sent him to the coronation of George V as a special U.S. Ambassador, and twice sent him to assist Nicholas II of Russia on irrigation and other engineering problems. In addition to Taft, Hammond also befriended Presidents Grant, Hayes, Roosevelt, and Coolidge.

Hammond became chairman of the U.S. Coal Commission, 1922–1923. His close friendship and longtime business associations with Frederick Russell Burnham, the highly decorated Scout who he knew from Africa, led Hammond to become a wealthy oil man when Burnham Exploration Company struck oil at Dominguez Oil Field, near Carson, California, in 1923.

May 1926: A Celebration of Hammond

editIn May 1926, an organization called "The Company of Friends of John Hays Hammond" sponsored eleven dinners around the world (Manhattan, San Francisco, London, Paris, Tokyo, Manila, etc.) in honor of Hammond. Over 10,000 people wrote tributes to Hammond, including: Hearst whose father gave him his first job, Woolf Barnato whose father (Barney Barnato) took him to South Africa, Sir Lionel Phillips who was condemned to death with him, the Guggenheims who employed him at a fabulous salary, former President Taft who offered him an ambassador position, and President Calvin Coolidge who consulted with him on the coal situation. The event was so extraordinary that Time magazine put Hammond on the cover of the May 10, 1926 issue and ran a biographical sketch on him called "Unique".[1]

He died of coronary occlusion on June 8, 1936, in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Family

editHe married Natalie Harris (1859–1931), of Harrisville, Mississippi (40 miles SSW south of the state capital, Jackson) on January 1, 1881, in Hancock, Maryland. Together they had four sons and one daughter:

Harris Hays Hammond (1881–1969), a financier, became president of Dominguez Oil Fields Company, which earned him $2 million in 1936, and president of Laughlin Filter Corporation, a small New Jersey company which manufactures centrifuges. In 1928, he and Anthony "Tony" Joseph Drexel Biddle Jr. were among the directors of Acoustic Products Co., which later became Sonora Products Corp. of America.[6]

John Hays Hammond, Jr. (1888–1965) was born in San Francisco, California. In 1893 he moved with his family to South Africa, and five years later the family moved to England. The family returned to the United States in 1900, and Hammond attended Lawrenceville School, started inventing, and went on to study at the Sheffield School of Yale University, graduating in 1910. He established the Hammond Radio Research Corporation in 1911 and eventually developed a radio controlled torpedo system for the navy, which he successfully demonstrated in 1918. Between 1926 and 1929, he built a medieval-style castle in Gloucester, Massachusetts.[7]

Natalie Hays Hammond (1904–1985) was born in Lakewood, New Jersey. Her estate in North Salem, New York was converted into the Hammond Museum & Japanese Stroll Garden in 1957.[8]

Nathaniel Harris Hammond (1902–1907) and Richard Pindle Hammond (1896–1980), composer, were the two other children.

John Hays Hammond died in 1936 at the age of 81 in an easy chair in his showplace at Gloucester, Massachusetts. He left an estate estimated at $2.5 million, mostly to his four surviving children: inventor John Hays Hammond Jr.; artist Natalie Hays Hammond; composer Richard Pindle Hammond; and financier Harris Hays Hammond.[6]

Awards

editThe Franklin Institute awarded John Hays Hammond Jr. the Elliott Cresson Medal for life achievement in 1959. He has been called the 'Father of Radio Control'.[citation needed]

Bibliography

editBooks

edit- The milling of gold ores in California (1887)

- A woman's part in a revolution (1897)

- The truth about the Jameson raid (1918)

- Great American Issues: Political Social Economic (1921)

- The engineer (Vocational series) (1922)

- The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond, volumes 1 and 2, (1935)

Other works

edit- South African Memories: Rhodes – Barnato – Burnham, published in Scribner's Magazine, vol. LXIX, January – June 1921

- Forward to, Scouting on Two Continents, by Major Frederick Russell Burnham, D.S.O., LC call number: DT775 .B8 1926. (1926)

See also

edit- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s – 10 May 1926

References

edit- ^ a b "Unique". Time Magazine. 10 May 1926. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ Charles Caldwell Hawley (2014). A Kennecott Story. The University of Utah Press. pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain Club Incorporates". New York Times. 19 January 1907.

- ^ "Rocky Mountain Club Ends a short but famous career; Its Huge Gifts of Money and Services in the War Gave It a Notable Record". New York Times. 4 March 1928.

- ^ a b c d Benjamin B Hampton (1 April 1910). "The Vast Riches of Alaska". Hampton's Magazine. 24 (1).

- ^ a b "Millennium Payment". Time Magazine. 16 August 1937. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ "Hammond Castle & Museum". Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ "Hammond Museum & Japanese Stroll Garden". Retrieved 2 December 2006.

Further reading

edit- Onselen, Charles van. The Cowboy Capitalist: John Hays Hammond, the American West, and the Jameson Raid (University of Virginia Press, 2018),

- Rotberg, Robert I. "The Jameson Raid: An American Imperial Plot?" Journal of Interdisciplinary History (2019) 49#4 pp 641–648.

- Frederick Russell Burnham Taking Chances, (1944) chapter XXXIV devoted to Hammond. LC call number: DT29 .B8. (1944)

- Spence, Clark C. Mining engineers & the American West; the lace-boot brigade, 1849–1933, . New Haven, Yale University Press, 1970. Yale Western Americana series 22. ISBN 0-300-01224-1 (1970)

- John Hays Hammond, Sr. Papers. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.