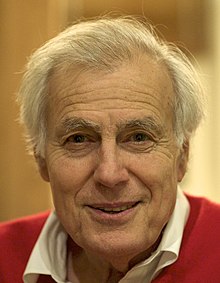

John Diamond (9 August 1934 – 25 April 2021) was a physician and author on holistic health and creativity.[1]

John Diamond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 August 1934 |

| Died | 25 April 2021 (aged 86) |

| Education | University of Sydney (M.B.B.S., 1957; Diploma in Psychological Medicine, 1962) |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Occupation(s) | Physician and Author |

| Website | drjohndiamond |

Biography

editBirth

editDiamond was born in Sydney in 1934. His parents, Rudolph Richard Diamond and Doris Lipert, were both pharmacists.[2]

Education and early career

editDiamond graduated from Sydney University Medical School in 1957 and was awarded his Diploma in Psychological Medicine in 1962. After graduating, he worked in private practice in Melbourne, and as a psychiatrist for the Victorian Department of Mental Hygiene (1960–62), the Repatriation Department in the State of Victoria (1963–68), the German consulate (1966–68), and the Royal Australian Air Force (1966–69).[2][1]

In 1968, Diamond conducted a series of interviews with the left-wing Australian politician Jim Cairns, who was at that time a Labour Party Member of Parliament, and later deputy-Prime Minister. The interviews, which were recorded on audiotape, have been described as "politically unique" by one of Cairns' biographers.[3] They were initiated by the Department of Political Science at Monash University, which was interested in researching the psychological motivations of politicians, but Cairns then continued them privately with Diamond over the course of a year.[3]

In the 1960s, Diamond was associated with Frank Galbally, a criminal defence lawyer in Australia, appearing as a medical witness in a number of homicide cases in which he successfully used novel approaches to argue the defendant's mental state as a mitigating circumstance.[4]

In 1971, Diamond moved to New York. He was to remain based in the US for the rest of his life, except for a four-year residence in England in the 1990s.[1] After his arrival in New York he worked for the Legal Aid Society and on an adolescent drug-abuse program at Mount Sinai and Beth Israel Hospitals in New York City.[2][5]

Professional associations

editHe was a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatry, a Foundation Member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, a Diplomate of the International College of Applied Kinesiology, and from 1978 to 1980 was President of the International Academy of Preventive Medicine.[1] He was an Honorary Advisor to the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation and their Japanese sister organization, the Koushikai Foundation.[6]

Personal life

editDiamond married three times. His first wife was Suzanne Gurvich, with whom he had three children, Ian, Kathie, and Peter. In the 1970s he married Betty Peele, and in 1994 the opera singer Susan Burghardt.[2] For many years, Diamond played drums in a jazz band which he founded, named the Diamond Jubilators. The band performed in hospitals and nursing homes.[2][1] He enjoyed photography and painting in the final years of his life.[2]

Life work

editIn the mid-1970s, Diamond moved to what he described as a more holistic approach to his work. At the heart of his work was the concept of Life Energy,[7] which was his term for the ancient Chinese concept of Qi. He believed that the flow of Life Energy underlies health at its most basic level, and that suffering, whether physical or psychological, is caused by blockages, often unconscious, to the flow.[2][1] His approach with those who came to see him was first to diagnose the impediments to the flow of Life Energy, and then help overcome them by drawing on a wide range of modalities, including acupuncture, verbal affirmations, physical procedures, and herbs.[2]

Diamond argued that everything we encounter in our lives impacts our Life Energy positively or negatively – for example, our nutrition, our thoughts, our social interactions, and the music we listen to. He taught that being aware of the effects of such stimuli is a first step to being able to control them, thus potentially allowing the person to keep their Life Energy at an optimum level. Diamond discussed what he believed was the relationship between acupuncture meridians and emotions. This relationship was to become far-reaching in his work, and from it he developed a model which delineated how emotions affect the body and vice versa.[5]

The therapeutic use of creativity was integral to Diamond's approach.[5] He regarded music in particular as central. Working as a psychiatrist in a Melbourne mental hospital in the 1960s, he witnessed first-hand the transformative effects of music on the residents. For example, a long-term patient with schizophrenia improved markedly when she began to play the piano that had been newly installed in her ward, and was soon discharged.[8][5] Influenced by these and other examples, Diamond systematically investigated the effects of many aspects of music, including different styles, performers, composers, instruments, acoustics, and recording techniques.[5] He similarly investigated the Life Energy of other art forms, including painting, photography, drama, literature, and poetry.

A fundamental component of Diamond's approach to developing a person's creativity for therapeutic purposes was what he termed "cantillation," from the Latin word for "to sing." Cantillation conventionally refers to the chanting of sacred texts, but Diamond applied it in a wider sense both of feeling loved, and in turn expressing that love to others through music, art, poetry and any other act of creativity. His technique was to reveal the activity unique to each person which allowed them to "cantillate," and then show them how to raise their Life Energy through the practice of that activity. He encouraged an altruistic approach, which he regarded as the most effective for therapeutic purposes.[9][10][2][1] In fostering cantillation, Diamond stressed the importance of the maternal relationship, which he termed Matrophilia, as an underlying factor in wellbeing.”[11]

The Institute for Music and Health

editDiamond founded The Institute for Music and Health, where he researched and taught his approach to the therapeutic power of music.[2] Based in New York's Hudson Valley, the Institute provided training and service in the area of "music for wellness,"[12] and disseminated Diamond's approach to the altruistic use of music through a variety of programs, including community outreach programs involving interactive and intergenerational music-making, connecting mainstream and special needs children with seniors.[13]

The Music Engagement Program

editDiamond's work has been cited as the inspiration for the Music Engagement Program (MEP) at the Australian National University School of Music.[14] According to Australian Capital Territory Arts Minister Joy Burch, as of mid-2013, the program reached 6,000 students, 120 teachers and 28 schools. Burch estimated that 2014-2016 student participation would increase to 10,000 students across ACT schools.[15]

Selected publications

edit- Your Body Doesn’t Lie. Sydney: Harper & Row, 1979. ISBN 0-446-35847-9. (Original title: BK Behavioral Kinesiology ISBN 0-06-010986-6).

- The Life Energy in Music (Volumes 1–3). Valley Cottage, NY: Archaeus Press, 1981, 1983, 1986. ISBN 1-890995-34-7, ISBN 1-890995-26-6, ISBN 1-890995-27-4.

- Life Energy: Unlocking the Hidden Power of Your Emotions to Achieve Total Well-Being. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1985. ISBN 1-55778-281-4.

- Facets of a Diamond: Reflections of a Healer. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 2002. ISBN 1-890995-17-7.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "John Diamond - Bio". Reachoutarts.org. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "John Diamond, 86: Bestselling author and pioneer of holistic healing through the arts". Thetimes.co.uk. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b Ormonde, Paul (1981). A Foolish Passionate Man: A Biography of Jim Cairns. Ringwood, VIC, Australia: Penguin Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-140059-75-X.

- ^ Galbally, Frank (1989). Galbally!: The Autobiography of Australia's Leading Criminal Lawyer. Ringwood, VIC, Australia: Viking Penguin. pp. 117–121. ISBN 0-670832-14-6.

- ^ a b c d e "In Memoriam: John Diamond, MD" (PDF). Townsend Letter. 459 (October 2021): 73–75.

- ^ "Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation". Ppnf.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "The Doctor Of Life Energy – A Tribute To John Diamond". PositiveHealthOnline. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Diamond, John (1981). Life Energy in Music, Vol. 1. p. 5.

- ^ "Dr. John Diamond's Music for the Soul" (PDF). East West: The Journal of Natural Health & Living. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Cantillation". Drjohndiamond.com. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Diamond, John (2011). Art for Healing. p. 1.

- ^ "Institute for Music and Health, Hudson Valley, New York". Musichealth.net. 27 March 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Yanks, Lauren (29 September 2012). "Music helps autistic connect". Poughkeepsie Journal, Living & Being. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Music Engagement Program". ANU.edu.au. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Arts outreach program to continue through ANU". ACT.gov.au. Retrieved 10 February 2014.