John Chilembwe (June 1871 – 3 February 1915) was a Baptist pastor, educator and revolutionary who trained as a minister in the United States, returning to Nyasaland in 1901. He was an early figure in the resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland (Malawi), opposing both the treatment of Africans working in agriculture on European-owned plantations and the colonial government's failure to promote the social and political advancement of Africans. Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Chilembwe organised an unsuccessful armed uprising against colonial rule. Today, Chilembwe is celebrated as a hero of independence in some African countries, and John Chilembwe Day is observed annually on 15 January in Malawi.

John Chilembwe | |

|---|---|

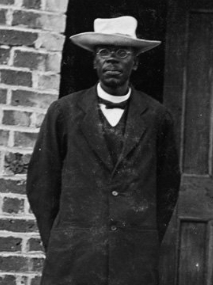

Chilembwe in 1914, one year before his death | |

| Born | June 1871 |

| Died | 03 February 1915 (age 43) |

| Cause of death | Killed in action |

| Alma mater | Virginia Theological Seminary and College |

| Years active | 1899–1915 |

| Known for | Chilembwe uprising |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Church | Baptist |

| Ordained | Lynchburg, Virginia, 1899 |

Early life

editThere is limited information about John Chilembwe's parentage and birth. An American pamphlet of 1914 claimed that John Chilembwe was born in Sangano, Chiradzulu District, in the south of what became Nyasaland, in June 1871. Joseph Booth also stated that Chilembwe's father was a Yao and his mother a Mang'anja slave, captured in warfare. This information was contemporary; in the 1990s, John Chilembwe's granddaughter stated that Chilembwe's father may have been called Kaundama, and was one of those who settled at Mangochi Hill during the Yao infiltration into Mang'anja territory, and that his mother may have been called Nyangu: his likely pre-baptismal name was Nkologo. However, other also quite recent sources give differing parental names.[1] Chilembwe attended a Church of Scotland mission from around 1890.

Influence of Joseph Booth

editIn 1892 he became a house servant of Joseph Booth, a radical and independent-minded missionary. Booth had arrived in Africa in 1892 as a Baptist to establish the Zambezi Industrial Mission near Blantyre. Booth was critical of the reluctance of Scottish Presbyterian missions to admit Africans as full church members, and later founded seven more independent missions in Nyasaland which, like the Zambezi Industrial Mission(Potts), focused on the equality of all worshippers. In Booth's household and mission, where he was closely associated with Booth, Chilembwe became acquainted with Booth's radical religious ideas and egalitarian feelings.[2][3]

Booth left Nyasaland with Chilembwe in 1897; he returned to Nyasaland alone in 1899 but left permanently in 1902, although he continued to correspond with Chilembwe. After 1906, Booth was strongly influenced by Millennialism, but the extent to which he retained influence over Chilembwe after 1902 or influenced him towards millennial beliefs is disputed, although Booth later strongly influenced Elliot Kenan Kamwana, the first leader of the Watchtower followers of Charles Taze Russell in Nyasaland.[4][5]

Education in the United States and relations with American and African Independent Churches

editIn 1897 Booth and Chilembwe traveled together to the United States. Because of the difficulties the two encountered when traveling together in the United States, Booth introduced Chilembwe to the Reverend Lewis G Gordon, Foreign Missions Secretary of the National Baptist Convention, who arranged for the latter to attend the Virginia Theological Seminary and College (now Virginia University of Lynchburg), a small Baptist institution at Lynchburg, Virginia where he almost certainly studied African-American history.[6]

The principal was a militantly independent Negro, Gregory Hayes, and Chilembwe both experienced the contemporary prejudice against negroes and was exposed to radical American Negro ideas and the works of John Brown, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass and others. He was ordained as a Baptist minister at Lynchburg in 1899.[7][8] After completing his studies at Lynchburg in 1900, he returned to Nyasaland in 1900 with the blessing of the Foreign Missions Board and financial assistance from the National Baptist Convention.[9]

For the first 12 years of his ministry after his return to Nyasaland, Chilembwe encouraged African self-respect and advancement through education, hard work and personal responsibility, as advocated by Booker T. Washington,[10] His activities were initially supported by white Protestant missionaries, although his relations with Catholic missions were less friendly.[11] After 1912, Chilembwe developed closer contacts with local independent African churches, including Seventh Day Baptist and Churches of Christ congregations, with the aim of uniting some or all of these African churches with his own mission church at the centre.[12] Some of Chilembwe's congregation had formerly been Watchtower followers and he maintained contact with Elliot Kamwana, but the influence of Watchtower's millennial beliefs on him is minimised by most authors except the Lindens.[13][14][15] Although the vast majority of those found guilty of rebellion and sentenced to death or to long terms of imprisonment were members of Chilembwe's church, a few other members of the Churches of Christ in Zomba were also found guilty.[16]

Return to Nyasaland and mission work

editIn 1900 Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland, in his own words, "to labour amongst his benighted race". Backed financially by the National Baptist Convention of America, Inc., which also provided two American Baptist helpers until 1906, Chilembwe started his Providence Industrial Mission (P.I.M.) in Chiradzulu district. In its first decade, the mission developed slowly, assisted by regular small donations from his American backers, and Chilembwe founded several schools, which by 1912 had 1,000 pupils and 800 adult students.[17]

He preached the values of hard-work, self-respect and self-help to his congregation and, although as early as 1905 he used his church position to deplore the condition of Africans in the protectorate, he initially avoided specific criticism of the government that might be thought subversive. However, by 1912 or 1913, Chilembwe had become more politically militant and openly voiced criticism over the state of African land rights in the Shire Highlands and of the conditions of labour tenants there, particularly on the A. L. Bruce Estates.[18]

It has also been claimed that Chilembwe preached a form of Millenarianism and that this may have influenced his decision to initiate an armed uprising in 1915.[19] There is very little direct evidence of what Chilembwe did preach although, at least in his first decade in Nyasaland, his main message was of African advancement through Christianity and hard work.[20][21] The evidence that has been interpreted as showing his millenarian views is dated from 1914 onward,[22][23] when he began baptizing many new church members without their first receiving instruction, as was normal Baptist practice.[24] However this evidence is ambiguous, and Chilembwe's activities have been more closely related to the Ethiopian movement of African churches breaking away, often with black American backing, from the more orthodox but European controlled Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist or other denominations, than being under the influence of overtly millenarian groups such as the Seventh-day Adventists.[25]

Colonial grievances

editIn the Shire Highlands, the most densely populated part of the protectorate, European estates occupied about 867,000 acres, or over 350,000 hectares, almost half of the best arable land. Relatively few local Africans remained on the estates when the owners introduced labour rents, preferring to settle on Crown Land where customary law entitled them to use (sometimes overcrowded) land belonging to the community, or to become migrant workers.[26][27] However, planters with large areas of available land but limited labour could engage migrants from Mozambique (who had no right to use community lands) on terms that Nyasaland Africans found unacceptable.[28] These were called "Anguru", a convenient term with derogatory implications employed by Europeans to describe a number of different peoples who originated in Mozambique but had migrated into Nyasaland, mostly those speaking one of the Makua languages, often the Lomwe language, who themselves used various names to refer to their places of origin.[29] They left Mozambique in significant numbers from 1899 when a harsh new labour code was introduced, and especially in 1912 and 1913 after a Mozambique famine in 1912. In 1912, the Colonial Office described them as working for such low wages as were "a record for any settled part of Africa". Many of those convicted after the rising were identified as "Anguru".[30]

Conditions on the estates where the "Anguru" became tenants were generally poor, and Africans both on estates and Crown Lands were subjected to an increase in Hut tax in 1912, despite food shortages. Chilembwe's Providence Industrial Mission was situated in an area dominated by the Magomero estate of A. L. Bruce Estates, named after a son-in-law of David Livingstone. From 1906, A. L. Bruce Estates developed and started to plant a hardy variety of cotton suitable for the Shire Highlands. Cotton required intensive labour over a long growing period, and the estate manager William Jervis Livingstone (reputed to be a distant relative of David Livingstone) ensured that 5,000 workers were available on the Magomero estate throughout that five- or six-month period by exploiting the obligations of the migrant labour tenancy system called thangata.[31] Alexander Livingstone Bruce, who controlled the A. L. Bruce Estates operations, instructed Livingstone not to allow any mission work to be carried on or schools to be opened on the Bruce Estates, although the company provided free medical and hospital treatment for workers.[32]

Alexander Livingstone Bruce held the considered view that educated Africans had no place in colonial society and he opposed their education. He also recorded his personal dislike for Chilembwe as an educated African; he considered all African-led churches were centres for agitation, and prohibited their being built on the Magomero estate. Although this prohibition applied to all missions, Chilembwe's mission was the closest; it became a natural focus for African agitation, and Chilembwe became the spokesman for African tenants on the Bruce Estates. Chilembwe provoked confrontation by erecting churches on estate land, which Livingstone burned down because he considered them as centres for agitation against the management and because they made potential claims on estate land.[33]

Reaction to the colonial system

editChilembwe was angered by Livingstone's refusal to accept the worth of African people, and also frustrated by the refusal of the settlers and government to provide suitable opportunities or a political voice to the African "new men", who had been educated by the Presbyterian and other missions in Nyasaland or in some cases had received a higher education abroad. A number of such men became Chilembwe's lieutenants in the rising.[34][35]

Although in his first decade at P.I.M., Chilembwe had been reasonably successful, in the five years before his death, he faced a series of problems in the mission and in his personal life. From around 1910, he incurred several debts at a time when mission expenses were rising and funds from his American backers were drying up. Attacks of asthma, the death of a daughter, and his declining eyesight and general health may have deepened his anger and alienation.[36]

Background to the 1915 uprising

editThe sources cited above agree that, after 1912 or 1913 the series of social and personal issues mentioned increased Chilembwe's bitterness toward Europeans in Nyasaland, and moved him towards thoughts of revolt and genocide. However, they treat the outbreak and effects of the First World War as the key factor in moving him from thought to planning to take action, which he believed it was his destiny to lead, for the deliverance of his people.[37][38] In the course of this war, some 19,000 Nyasaland Africans served in the King's African Rifles, and up to 200,000 others were forced to be porters for varying periods, mostly in the East African Campaign against the Germans in Tanganyika, and disease caused many casualties among them.[39] One of the earliest campaigns, a German invasion of Nyasaland and a battle at Karonga in September 1914 caused Chilembwe to write an impassioned letter against the war to the "Nyasaland Times" newspaper, saying that a number of his countrymen, "have already shed their blood", others were being "crippled for life" and "invited to die for a cause which is not theirs". The war-time censor prevented publication of the letter, and by December 1914, Chilembwe was regarded with suspicion by the colonial authorities.[40]

The Governor decided to deport Chilembwe and some of his followers, and approached the Mauritius government asking them to accept the deportees a few days before the rising started. The censoring of Chilembwe's letter appears to be the trigger moving him from conspiracy to action. He began the detailed organisation for a rebellion, gathering together a small group of Africans, educated either at the Blantyre Mission or the schools of the independent, separatist African churches in the Shire Highlands and Ncheu District, as his lieutenants. In a series of meetings held in December 1914 and early January 1915, Chilembwe and his leading followers aimed at overturning colonial rule and supplanting it, if possible. However, it is possible that he learnt of his intended deportation, and was forced to bring forward the date of his revolt, making the prospects of its success more unlikely, and turning it into a symbolic gesture of protest.[41] When he brought forward the date of the Shire Highlands rising, Chilembwe was unable to ensure that it could still be coordinated with the planned rising in the Ntcheu District, which was therefore largely abortive.[42] The failure in Ncheu District may also relate to the pacifism of many Seventh Day Baptist and Watchtower followers who were expected to rise there.[43]

1915 uprisings and death

editThe aims of the rising remain unclear, partly because Chilembwe and many of his leading supporters were killed, and also because many documents were destroyed in a fire in 1919. However, use of the theme of "Africa for the Africans" suggests a political motive rather than a purely millennial religious one.[44] Chilembwe is said to have drawn parallels between his rising and that of John Brown, and stated his wish to "strike a blow and die" immediately before the rising started.[45][46] However, this is based solely on what George Simeon Mwase, who was absent from Nyasaland in 1915, wrote 17 years after the event. Mwase claimed the phrase, "…strike a blow and die…" was said by Chilembwe several times, but it is not recorded elsewhere, and it conflicts with the actual course of the uprising, during which several of the chosen leaders stayed home and many followers fled once troops appeared.[47]

The first part of Chilembwe's plan was to attack European centres in the Shire Highlands on the night between 23 and 24 January 1915 to obtain arms and ammunition, and the second was to attack European estates in the same area simultaneously. Most of Chilembwe's force of about 200 men were from his P.I.M. congregations in Chiradzulu and Mlanje, with some support from other independent African churches in the Shire Highlands. In the third part of the plan, the forces of the Ncheu revolt based on the local independent Seventh Day Baptists would move south to link up with Chilembwe. He hoped that discontented Africans on European estates, relatives of soldiers killed in the war and others would join as the rising progressed.[48]

It is uncertain if Chilembwe had definite plans in the event of failure; some suggest he intended to seek a symbolic death, others that he planned to escape to Mozambique.[49] The first and third parts of the plan failed almost completely: some of his lieutenants did not carry out their attacks, so few arms were obtained, the Ncheu group had failed to form and move south, and there was no mass support for the rising.[50]

The attack on European estates was largely one on the Bruce estates, where William Jervis Livingstone was killed and beheaded and two other European employees killed. Three African men were also killed by the rebels; a European-run mission was set on fire, a missionary was severely wounded and a girl died in the fire. Apart from this girl, all the dead and injured were men, as Chilembwe had ordered that women should not be harmed. On 24 January, which was a Sunday, Chilembwe conducted a service in the P.I.M. church with Livingstone's impaled head prominently displayed. However, by 26 January he realised that the uprising had failed to gain local support. After avoiding attempts to capture him and apparently trying to escape into Mozambique, he was tracked down and killed by an askari military patrol on 3 February.[51][52] An assistant magistrate that had inspected Chilembwe's body informed the government inquiry that he had been "wearing a dark blue coat, a coloured shirt and a striped pyjama jacket over the shirt and grey flannel trousers. With the body was brought in a pair of spectacles, a pair of pince nez and a pair of black boots". Even when being tracked down by patrols on the Mozambique border Chilembwe had continued to maintain his appearance as a "civilised gentleman".[53]

Aftermath of the uprising

editMost of Chilembwe's leading followers and some other participants in the rising were executed after summary trials under martial law shortly after it failed. The total number of those killed is unclear, because extrajudicial killings were carried out by European members of the Nyasaland Volunteer Reserve.[54][55][56] The government also shut down Chilembwe's Providence Industrial Mission. The PIM remained inactive until 1926, when it reopened under the leadership of former student Daniel Sharpe Malekebu.

A Commission of Enquiry into Chilembwe's uprising was appointed and, at its hearings in June 1915, the European planters blamed missionary activities while European missionaries emphasised the dangers of the teaching and preaching by independent African churches like those led by Chilembwe. Several Africans who gave evidence complained about the treatment of workers on estates, but were largely ignored. The official enquiry needed to find causes for the rising and it blamed Chilembwe for his mixture of political and religious teaching, but also the unsatisfactory conditions on the A L Bruce Estates and the unduly harsh regime of W. J. Livingstone.[57] The enquiry heard that the conditions imposed on the A L Bruce Estates were illegal and oppressive, including paying workers poorly or in kind (not in cash), demanding excessive labour from tenants or not recording the work they did, and whipping and beating both workers and tenants. The abuses were confirmed by Magomero workers and tenants questioned by the Commission in 1915.[58]

Livingstone alone was blamed for these unsatisfactory conditions, and the resident director of the A L Bruce Estates, Alexander Livingstone Bruce, who had absolute control over estate policy and considered that educated Africans had no place in colonial society, escaped censure.[59] The concept that the only appropriate relationship between Europeans and Africans was that of master and servant was at the heart of colonial society, led by the landowners. This concept may have been what Chilembwe aimed to fight against with his schools and self-help schemes, and ultimately why he turned to violent action,[60] although see also[61] for an alternate viewpoint.

Nyasaland independence and legacy

editNyasaland gained independence in 1964, taking the name Malawi. Chilembwe's likeness was seen on the obverse of all Malawian kwacha notes from 1997 until May 2012, when new notes were launched; the 500-kwacha note still carries his portrait. Since December 2016, the newly introduced 2000-kwacha note also carries his picture.[62]

John Chilembwe Day is observed annually on 15 January in Malawi.[63][64]

A larger-than-life statue of John Chilembwe was unveiled in London's Trafalgar Square in September 2022.[65]

Personal life

editChilembwe had a wife named Ida. They had two sons, John (nicknamed Charlie) and Donald, who were born at unknown dates, in addition to a daughter, Emma, who died during infancy. After Chilembwe was killed, Ida took care of the two sons until her death amidst the 1918 influenza outbreak, where afterwards, they were under the care of their grandmother until she herself died in 1922. They were then entrusted into the hands of the Blantyre Mission and government as orphans. Charlie and Donald struggled to live up to their father's legacy; Charlie spent his last years at Blantyre working as a sweeper until his death in 1971, while Donald, struggling to find work, largely vanishes from the historic record in the 1930s. It is speculated that he went to the United States or South Africa.[66]

References

edit- ^ D. T. Stuart-Mogg (1997). "A Brief Investigation into The Genealogy of Pastor John Chilembwe of Nyasaland and Some Thoughts upon the Circumstances Surrounding his Death", The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 44–7.

- ^ G. Shepperson and T. Price (1958). Independent African. John Chilembwe and the Origins, Setting and Significance of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 25, 36–8, 47.

- ^ K. E. Fields (1985). Revival and Rebellion in Colonial Central Africa, Princeton University Press, pp. 125–6. ISBN 978-069-109409-0.

- ^ K. E. Fields (1985). Revival and Rebellion in Colonial Central Africa, pp. 99–100, 105.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem", The Journal of African History, Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 633.

- ^ Marcus Garvey (ed. R. A. Hill), (2006).The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Vol. IX: Africa for the Africans, 1921–1922. Oakland, University of California Press, p. 427.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, pp. 79, 85–92, 112–118, 122–123.

- ^ R. I. Rotberg (1970). "Psychological Stress and the Question of Identity: Chilembwe's Revolt Reconsidered", in R. I. Rotberg and A. A. Mazrui, eds, Protest and Power in Black Africa, New York: Oxford University Press, 356-8. ISBN 978-019-500093-1

- ^ Marcus Garvey (ed. R. A .Hill) (2006). The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Vol. IX: Africa for the Africans, 1921–1922. Oakland, University of California Press, pp. 427–8.

- ^ G. Shepperson and T. Price (1958). Independent African. John Chilembwe and the Origins, Setting and Significance of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 166, 417

- ^ B. Morris (2016), "The Chilembwe Rebellion", The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 68, No. 1, p. 39.

- ^ R. Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", African Historical Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2, p. 307.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, p. 417.

- ^ R. I. Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, pp. 77, 85.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem", The Journal of African History, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 631–3.

- ^ L. White (1984). "'Tribes' and the Aftermath of the Chilembwe Rising", African Affairs, Vol. 83, No. 333, pp. 522–3.

- ^ G. Shepperson and T. Price (1958). Independent African. John Chilembwe and the Origins, Setting and Significance of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 171, 248. – For a Providence Industrial Mission (PIM) history emphasizing the missionary work see: Patrick Makondesa, The Church History of Providence Industrial Mission, Zomba: Kachere, 2006.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", pp. 306–7.

- ^ R. I. Rotberg (1971). "Psychological Stress and the Question of Identity: Chilembwe's Revolt Reconsidered", in R. I. Rotberg and A . A. Mazrui (editors), Protest and Power in Black Africa. New York, p. 141.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", pp. 306–7.

- ^ J. McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, Woodbridge: James Currey, p. 133.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 142.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem". The Journal of African History. Vol. 12, p. 640.

- ^ L. White (1987). Magomero: Portrait of an African Village, p. 133, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32182-4

- ^ T. Jack Thompson (2015). "Prester John, John Chilembwe and the European Fear of Ethiopianism", The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 20–22.

- ^ B. Pachai (1978). Land and Politics in Malawi 1875–1975, Kingston (Ontario): The Limestone Press, pp. 36–7.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, p. 18.

- ^ L. White (1984). "'Tribes' and the Aftermath of the Chilembwe Rising", pp. 513–15.

- ^ T. Price (1952). "The Name 'Anguru'", The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 5, No. 1, p. 25.

- ^ L. White (1984). "'Tribes' and the Aftermath of the Chilembwe Rising", pp. 515–18, 523.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 130–2. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem", p. 633.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", p. 307.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, pp. 240–50.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem", pp. 633–4.

- ^ R. I. Rotberg (1970). "Psychological Stress and the Question of Identity: Chilembwe's Revolt Reconsidered", pp. 365–6.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, pp. 234–5, 263.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", pp. 308–9.

- ^ M. E. Page (2000). "The Chiwaya War": Malawians and the First World War, Boulder (Co), Westview Press, pp. 35–6, 37–41, 50–3.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 81–3

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", pp. 309–11.

- ^ J. Linden and I. Linden (1971). "John Chilembwe and the New Jerusalem", p. 629

- ^ K. E. Fields (1985). "Revival and Rebellion in Colonial Central Africa", pp. 125–6.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, pp. 504–5.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, p. 84.

- ^ Shepperson and Price (1958). Independent African, p. 239.

- ^ T. Price (1969), Review of "Strike a Blow and Die" by George Simeon Mwase and Robert I. Rotberg, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 39, No. 2 p. 195.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", pp. 310–12.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 84–6.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, Woodbridge: James Currey, p. 141.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", p. 313.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 142.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 137.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 87–91.

- ^ Tangri (1971). "Some New Aspects of the Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915", p. 312.

- ^ P. Charlton (1993). "Some Notes on the Nyasaland Volunteer Reserve", The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 35–9.

- ^ L. White (1984). "'Tribes' and the Aftermath of the Chilembwe Rising", pp. 523–4.

- ^ Rotberg (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 78–9.

- ^ McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 130–31.

- ^ L. White (1984). "'Tribes' and the Aftermath of the Chilembwe Rising", pp. 524–5.

- ^ Rotberg, Robert. "Psychological Stress and the Question of Identity: Chilembwe's Revolt Reconsidered", in Protest and Power in Black Africa, pp. 337–373. Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ^ "Malawi new 2,000-kwacha note (B163) confirmed". BanknoteNews. 30 December 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Official Public Holidays in Malawi".

- ^ Irele, Abiola; Jeyifo, Biodun (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-533473-9.

- ^ Sippy, Priya (28 September 2022). "Malawi's John Chilembwe gets statue in London's Trafalgar Square". BBC News. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Stuart-Mogg, David (2010). "John Chilembwe's wife and progeny". The Society of Malawi Journal. 63 (2): 25–38.

External links

edit- Chilembwe.com: "Who is John Chilembwe" (1996).

- Brockman, N. C. Chilembwe, John. An African Biographical Dictionary, 1994.

- Rotberg, R. I. John Chilembwe: Brief life of an anticolonial rebel: 1871?–1915. Harvard Magazine, March–April 2005: Volume 107, Number 4, Page 36.