Joseph Arridy (/ˈærɪdi/; April 29, 1915 – January 6, 1939)[1][2] was an American man who was falsely convicted and wrongfully executed for the 1936 rape and murder of Dorothy Drain, a 15-year-old girl in Pueblo, Colorado. He was manipulated by the police to make a false confession due to his mental incapacities. Arridy was mentally disabled and was 23 years old when he was executed on January 6, 1939.

Joe Arridy | |

|---|---|

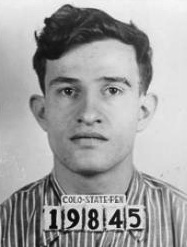

Arridy's mug shot | |

| Born | April 29, 1915 |

| Died | January 6, 1939 (aged 23) |

| Cause of death | Execution by gas chamber |

| Known for | Being wrongfully executed |

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (162 cm) |

| Criminal status | |

| Conviction(s) | First-degree murder, rape (pardoned) |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Many people at the time and since maintained that Arridy was innocent. A group known as Friends of Joe Arridy formed and in 2007 commissioned the first tombstone for his grave. They also supported the preparation of a petition by David A. Martinez, Denver attorney, for a state pardon to clear Arridy's name. Another man, Frank Aguilar, was convicted and executed for the same crime two years before Arridy's execution.[3]

In 2011, Arridy received a full and unconditional posthumous pardon by Colorado Governor Bill Ritter (72 years after his death). Ritter, the former district attorney of Denver, pardoned Arridy based on questions about the man's guilt and what appeared to be a coerced false confession.[3][4][5] This was the first time in Colorado that the governor had pardoned a convict after execution.

Early life

editArridy was born in 1915 in Pueblo, Colorado, to Mary and Henry Arridy (originally Arida; Arabic: عَرِيضَّة), Maronite Christian immigrants from Bqarqacha,[a] a village in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Ottoman Syria.[b][8] Henry came to the United States in search of work in 1909 via the USS Martha Washington over Patras, Greece, being joined by his wife in 1912. The couple were first cousins and did not speak English. Henry took a job as a molder with a Colorado Fuel and Iron steel mill in Pueblo that he learned was hiring workers.[2][9] In census records, the surname of the parents was inconsistently spelled as "Areddy" (1920),[10] "Arddy" (1930),[11] and "Arriag" (1940).[12]

John Arridy, the eldest of the couple's three surviving children, was non-verbal for the first five years of his life and only spoke in short simple sentences. Even as an adult, he generally did not talk at all unless spoken to first. After he attended one year at Bessemer Elementary School, his principal told his parents to keep him at home, saying that he could not learn. Arridy did not socialize with other children in his neighborhood, instead preferring to wander town, hammer nails, and make mud pies, a habit he kept up into his mid-teens.[8]

Admission to training school

editIn 1925, Henry Arridy lost his job and appealed to neighbors to help him write letters to find a place for his son, as Henry was partially illiterate (able to read, but not write). In October of the same year, Arridy was admitted at the age of ten to the State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives in Grand Junction, Colorado. It was noted during formal psychological exams, including a Binet-Simon test, that Arridy was "extremely concrete in his thinking and totally unable to think abstractly about anything", noting he could not tell the difference between a stone and an egg or wood and glass, with other examples including his inability to count past five without assistance, tell apart colors, or name the weekdays. Examiners at the home also had Arridy's family undergo several psychological tests and concluded that his mother Mary was "probably feeble-minded" and his younger brother George considered a "high moron". Henry regretted sending his son away and requested his full release only ten months later, with Arridy returning to Pueblo on August 13, 1926.[2][9]

On September 17, 1929, while Henry was serving a prison sentence for bootlegging, Arridy was sexually assaulted by a group of teen boys, who sodomized him and forced Arridy to perform oral sex on them. Arridy's juvenile probation officer walked in on the scene and wrote a complaint letter to the school's superintendent Dr. Benjamin Jefferson. The probation officer misrepresented the rape as consensual, citing the same-sex and interracial nature of the assault as evidence that Arridy posed a moral danger to society. The officer wrote "I picked him up this morning for allowing some of the nastiest and dirtiest things done to him that I have ever heard of… The boy MUST [sic] be returned. The people of the neighborhood are indignant as they are afraid of the boy and think he never should have been turned loose... I cannot understand why boys of the mentality of this one are allowed to return home". The officer included a separate sheet listing Arridy's "myriad moral digressions", such as "manipulating the penis of Negro boys with his mouth"[9] and "allowing […] boys to enter the ‘dirty road’",[2] excusing the choice of words by claiming that he "would be more technical, but do not know the terms", and threatened to shift blame onto Jefferson for allowing Arridy to leave the training school. The fate of the assailants, if any, was not addressed in the letter.[8]

Arridy was subsequently recommitted to the school, where it was reported that he could only be taught "tasks of not too long duration" such as mopping floors or washing dishes. Arridy was often mistreated, beaten, and manipulated by his peers, only ever becoming close with one Mrs. Bowers, a kitchen worker who supervised his chores, during his seven-year stay. Dr. Jefferson made note of Arridy's suggestibility and need for constant guidance, outlining an incident in which Arridy falsely took responsibility for stealing cigarettes. Appeals by Arridy's family for him to be discharged were blocked by Jefferson, who claimed that their son was being kept for safety reasons due to his "perverse habits".[8][9]

On August 8, 1936, 21-year-old Arridy, along with at least four other young men, left the school grounds and, mimicking the behaviour of train-hopping laborers in the nearby railyards, he stowed away in freight carts and traveled through Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

Attack

editOn the evening of August 14, 1936, two girls of the Drain family were attacked while sleeping at home in Pueblo, Colorado. An intruder entered the house through the unlocked front door and bludgeoned 15-year-old Dorothy and her 12-year-old sister Barbara Drain with a bladed weapon, believed to be the blunt side of a hatchet. Dorothy was also raped; she died from the hatchet attack, while Barbara survived after spending two weeks in a coma.[13] Their parents had been out of the house that night while their younger brother, who slept in an adjacent room, was left unharmed.[14][15]

A fellow runaway from the school, Ben Harvey, would later tell workers that he and Arridy had passed through Pueblo only once, in the late hours of August 16, to visit his family in Bessemer, unaware that they had moved to a different part of town, and getting on a train to Denver shortly after.[9] Following Arridy's arrest, Val Higgins, chairman of the state board of control in charge of the school, launched an independent investigation into the accusation against Arridy on September 1.[16][17]

By August 18, five suspects had been detained and a reward of $1000 ($22,709.64 in 2024) was issued for the arrest of the perpetrator. As neighbors who saw the perpetrator described him as "swarthy", police actively searched for a known African-American offender as a suspect, but also sought a match with the fingerprints of escaped Colorado State Hospital at Pueblo inmate Joseph Qualteri, of Italian descent, who was killed by police outside of Englewood, both to no success.[18][19][20]

Arrest and conviction

editAfter several weeks of train-hopping, Arridy arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming on August 20 at noon and not long after, he walked up to a kitchen car and asked the workers for food. The car's supervisors, Mr. and Mrs. Glen Gibson, allowed Arridy to stay with the crew, gave him clean clothes and allowed him to work as a dishwasher in exchange for meals. On August 26, while in Archer, the kitchen car's train was bound to head out of state and as Arridy was not officially an employee, the Gibsons told Arridy he could not go with them and drove him back to the railyard in Cheyenne.[1][8] Arridy wandered around the railyard for several more hours, presumably waiting for another train, until he was arrested by railroad detectives George Burnett and Carl Christianson, as the detectives believed Arridy could one of many army deserters from Fort Logan, due to his khaki-colored clothing.[21][22][8] Arridy was brought to jail, where he was questioned by Laramie County Sheriff George J. Carroll.

Confession through Sheriff Carroll

editCarroll was aware of the widespread search for suspects in the Drain murder case and when Arridy revealed under questioning that he was a native of Pueblo and had recently traveled through the town by way of a train after leaving Grand Junction, Colorado, Carroll began to question him about the Drain case. Carroll questioned Arridy about any "girl friends" he had in Pueblo, asking "Well, Joe, you like the girls pretty well don’t you?" and stating "You have had several girls during your lifetime", both of which Arridy answered with yes. Carroll then reportedly asked "If you like to go around with girls so much, why do you hurt them?", to which Arridy allegedly responded "Well, I didn't mean to". Carroll further claimed that Arridy openly confessed to the murder of "the two little girls in Pueblo" and to have done it "just for meanness", reassuring Carroll that "If they let me alone I'll be good after this", but made no mention of rape.[22][23] After around 90 minutes of interrogation, Carroll contacted the Pueblo police Chief J. Arthur Grady about Arridy before calling the local press, who reported the sheriff's news the next morning on August 27, naming Arridy as the sole perpetrator in the Drain attacks, though his last name was initially misspelled as "Arddy" or "Ardy".[24][25][26][27][28]

Frank Aguilar

editOnly a few hours later, Carroll was informed by Grady that he had learned that his officers had already arrested a man considered to be the prime suspect: 33-year-old Francisco A. "Frank" Aguilar, a laborer with the Works Progress Administration from Mexico.[29][30][31] Aguilar, an ethnic Yaqui,[32] had worked for the father of the Drain girls, Riley Drain, who was a foreman with the WPA,[33] and had been fired shortly before the attack. The three-room apartment Aguilar shared with his mother, wife, and children was searched by police, with investigators finding an axe head with notches matching the wounds inflicted on both Drain girls, as well as a calendar with the date August 15 marked, with photographs of nude women and newspaper clippings containing articles about "sex slayings" taped to the surrounding wallpaper.[23][34] Shortly before his execution, Aguilar was also connected to a murder that occurred earlier on August 2 at a home only three blocks away from the Drain residence, when he bludgeoned 72-year-old Sally Crumply, as well as her 48-year-old niece Lilly McMurtree and four-year-old grandson Burton Beach, who survived the attack,[22] and a third undisclosed murder that occurred in 1934; McMurtree's son Floyd had been held in a mental asylum after being wrongly accused.[35][36][37] Aguilar had been already arrested on August 16 when he attended Dorothy Drain's funeral, after he attracted the attention of law enforcement for being dressed in work overalls, cutting in line twice to see the casket and forcefully handing the deceased's father 25 cents in nickels "to help the family". He was put in custody after asking two officers where to find Riley Drain and repeatedly hinted at his closeness to the family, particularly his daughters, but did not admit to the attack while in custody, with his mother providing an alibi that he had been home the night of the attacks. Grady was only informed of Aguilar as a suspect after an analysis of scrapings from Aguilar's fingernails showed fibers of blue-dyed chenille fabric, the same material that the bedsheets of the Drain girls had been made of.[23][22]

Meanwhile, Sheriff Carroll subsequently claimed that Arridy "kept changing his story," and while being transported to Pueblo to participate in a re-enactment at the Drain residence on August 27, Arridy reportedly confessed again and had eventually told him several times he had "been with a man named Frank" at the crime scene.[36] Several details had been changed from the first confession, such as Arridy's initial statement that he had used a club in the attack and that he waited outside the Drain residence by himself hidden in the bushes. Other parts of the confession were left out entirely, such as the claim that Arridy ran back home after the crime and was sheltered by his family. Arridy repeatedly provided wrong addresses that were either incomplete or led to the neighborhood Arridy had grown up in, but his family had moved out of during his stay at the school. The Arridy family, as well as two of Joe Arridy's female cousins, Christine and Frances Marguerite, who lived close to the Drain residence, were nevertheless held in custody throughout the day, with two axes being confiscated from the Marguerite home.[38] Despite these inconsistencies being printed in several early reports on the attack, Carroll was never questioned about them in court.[8][9][24][39]

On August 28, Aguilar confessed to the crime. On August 29, he was sent to Colorado State Penitentiary for holding, reportedly due to lynching threats after a public posting circulated for a "necktie party". Sheriff Carroll had arranged with Pueblo Sheriff Lewis Worker to have Aguilar meet with Arridy in the penitentiary, and tell both that the other was arrested as an accomplice.[36][40] While Arridy identified Aguilar by saying "That's Frank", Aguilar initially told police he had never seen or met Arridy. However, on September 2, a stenographed five page document obtained through a joint nine-hour interrogation of Aguilar and Arridy by the penitentiary's warden Roy Best in presence of District Attorney French L. Taylor was released, in which Aguilar affirmed that Arridy was an accomplice in the killings. A total of six pre-prepared questions, which were always structured to include mention of Arridy, incriminated Arridy, with Aguilar having provided no further comments and with his responses consisting almost entirely of some variation of "yes" when asked to confirm.[c] Aguilar was the only one to sign the statement with "X" as the signature, while Arridy, who remained silent throughout the interrogation, did not, which D.A. Taylor acknowledged, but assumed that Arridy was under the influence "of marijuana or something similar". The prevailing narrative, published in The Pueblo Chieftain, was now that Aguilar and Arridy, who were both characterized as sexual deviants, had met by chance in the Bessemer area of Pueblo on the evening of August 14. Aguilar had planned the attack ahead of time and let Arridy join him in carrying out the Drain attacks together before Arridy left town via train. Aguilar recanted shortly after, claiming Best and Grady had threatened him with "terrible things" and that there would be "a dead Mexican" if he did not implicate Arridy.[8]

On August 29, Chief Hugh Davis Harper of the Colorado Springs Police Department announced that Arridy had been positively identified as having assaulted Helen O'Driscoll on August 23, after the victim had identified Arridy's picture in the newspaper as her assailant. Arridy had confessed to the assault upon being asked, but eyewitnesses and coworkers placed Arridy at his workplace in the railroad kitchen in Cheyenne, 170 miles away from Colorado Springs, at the time, after which the charge was dropped. Similarly, Saul Kahn, a pawnbroker had claimed that Arridy bought a gun from him the day of the attack on the Drain residence, but this allegation was dismissed because Kahn, who repeatedly changed the date he supposedly met Arridy, could not provide evidence for the purchase. Kahn had also stated that Arridy paid in cash, despite his lack of funds and inability to count, and that he introduced himself by his full name Joseph Arridy, when he only ever called himself Joe.[8]

At the joint hearing of Arridy and Aguilar on October 9, 1936, both men entered a not guilty plea.[41] Aguilar's case was processed first, with his attorney Vasco G. Seavy, aware of Arridy's mental disability, claiming that Aguilar was similarly "feeble-minded" and thus of diminished capacity. Seavy brought up that Aguilar's brother had been confined to a mental asylum before he was deported back to Mexico and claimed that Arridy had privately confessed to him that he acted alone.[42] On December 22, Aguilar was convicted of the rape and murder of Dorothy Drain, for which he was sentenced to death. He was executed on August 13, 1937, in Colorado State Penitentiary, aged 34. During the execution, a male spectator, 40-year-old Adlai "Ad" Hamilton,[43] died of a heart attack.[8][9][44] The physician attending the execution was busy recording Aguilar's vital signs before he tended to Hamilton, who was determined to have died the same moment as Aguilar.[32] Before the execution, Aguilar met Arridy in his cell before having a final visit with his mother Guadalupe Aguilar (also named as Lupe Rene Aguilar), who collapsed during the visitation; Aguilar initially appeared unconcerned with her state, as fainting spells had become common at the end of their meetings.[45] Aguilar had a last meal of tomato soup, toast, fried eggs, french fries, coffee and donuts, which he shared with guards and the prison chaplain, then made his last statement to the prison warden, "I am going to my death bravely. Nobody heard anything of a man of my race dying with anything but a smile on my lips".[22] Articles about his execution reported that Aguilar had to be dragged to the execution chamber crying, believing his mother had died or was dying.[46] Doctors described her condition as grave and expected her to die due to being "grief prostrate",[32] but ultimately survived.[47] On February 3, 1938, Aguilar's three-year-old daughter Victoria was killed in a housefire. The death was briefly investigated as a homicide due to head trauma to Victoria's skull[48] before being ruled as accidental due to an unattended stove.[49] After Aguilar's wife deserted the family, Guadalupe Aguilar and her surviving two grandchildren relocated to Mexico.[43]

Trial

editWhen the case was finally taken to trial on February 8, 1937, Arridy's lawyer C. Fred Barnard pleaded insanity to avoid the death penalty for his client. Sherriff George Carroll testified eight separate times in court and contended that Arridy was mentally fit and aware of his actions, claiming that he was articulate during all questioning, provided accurate information during the crime scene reenactment (which several of Carroll's deputies present at the time vouched for) and that Arridy had shown guilt by displaying "great remorse" in private. Carroll further claimed that although Arridy was ignorant of what sex was, he told Carroll during his initial confession that he had "screwed" the Drain girls. Despite previously describing Arridy as "a nut [who] told us two or three different stories" and "to all appearances, unquestionably insane" to colleagues, Carroll now voiced his suspicions that Arridy had acted alone and falsely implicated the already convicted Aguilar.[2][9] Colorado State Hospital psychiatrist J. L. Rosenbloom stated that "if it was [Arridy's] desire to please, he had a tendency to say 'yes' to anything with a smile" and supported the insanity plea, as in his opinion, Arridy was "definitely insane in the legal meaning of the word... vaguely knows it is wrong to commit murder, but does not know why".[22] Judge Harry Leddy ruled Arridy to be sane,[50] while acknowledged by three state psychiatrists to be so mentally limited as to be classified as an "imbecile", a medical term at the time. They said he had an IQ of 46, and the mind of a six-year-old.[34][51] They noted he was "incapable of distinguishing between right and wrong, and therefore, would be unable to perform any action with a criminal intent".[1][2] To showcase Arridy's mental development, Arridy's lawyer allowed prosecutor Ralph J. Neary to ask him several questions, ranging from case-related to common household knowledge. Among other things, Arridy did not know who Franklin Roosevelt or George Washington were, said that he had never seen a hatchet and did not know what one looked like, could not tell the difference between a nickel and a dime, and was unable to recognize his own father, whom he had not seen for 8 years by this point, when he was pointed out in the court room. He also stated that he did not know who Dorothy Drain or Frank Aguilar were, this having been the first time he was directly questioned about them by a non-police entity, and showed no understanding of either the court or his own trial, which he only described as "Talking... Talking about me".[8][22]

On April 17, a jury convicted Arridy of the murder, largely due to his false confession and sentenced to death, with the execution date set for May of the same year.[34][52] Studies since then have shown that persons of limited mental capacity are more vulnerable to coercion during interrogation and have a higher frequency of making false confessions. The only physical evidence against him was a single strand of hair that was supposedly matched with one of Arridy's. Pathologist Frances McConnell, whose work had partially helped convict Frank Aguilar through his finger nail samples, compared the hairs under a microscope and identified the hair as belonging to a specific ethnicity through visual comparison, in this case claiming that it bore the characteristics of an "American Indian". The evidence was accepted, even though it ran contrary to the fact that Arridy was of recent Syrian ancestry and Arridy's race being (incorrectly) listed as "Hispanic" on prison documents,[d][54][55] with visual matching of hairs having since been proven to not be an accurate act of measure.[8] An account of McConnell's involvement in the trial also claims that the aforementioned fingernail sample was taken from Arridy, not Frank Aguilar, who actually was of indigenous descent, but is not mentioned at all.[56] Barbara Drain had testified that Aguilar had been present at the attack, but not Arridy. She could identify Aguilar because he had worked for her father.[8]

After the trial, Sheriff Carroll and the two railroad detectives who had arrested Arridy were each rewarded with $1000 (equivalent to $21,194 in 2023) for their part in resolving the case. In the days after the trial, Benjamin Jefferson, who had read a statement corroborating the psychiatrists' findings in court, gave a speech to the press and used the example of Joe Arridy to advocate for eugenics, stating that his "imbecility" was the result of a "diseased germ plasma that was never allowed to unfold" and made a public plea to Colorado legislation to pass a law that would mandate the sterilization of "imbeciles", i.e. individuals with an IQ below 50.[8]

Appeals

editAttorney Gail L. Ireland, who later was elected and served as Colorado Attorney General and Colorado Water Commissioner, became involved as a pro bono defense counsel in Arridy's case after his conviction and sentencing. While Ireland won ten delays of Arridy's execution, he was unable to get his conviction overturned or commutation of his sentence. He noted that Aguilar had said he acted alone, and medical experts had testified as to Arridy's mental limitations. Ireland said that Arridy could not even understand what execution meant. "Believe me when I say that if he is gassed, it will take a long time for the state of Colorado to live down the disgrace," Ireland argued to the Colorado Supreme Court.[34] Ireland was supported in his appeals by clergy of the Catholic Church. One of them, Leonard Schwinn, abbot of Holy Cross Abbey, called the sentence into question in a written statement to the governor, saying "I don't think the state ought to be executing children".[57] Arridy received nine stays of execution as appeals and petitions on his behalf were mounted, during which time the electric chair was phased out as an execution method in Colorado and replaced by the gas chamber.[58][59][60]

Death row

editDuring the appeals process, Arridy was held alongside three other condemned men: Angelo Agnes, Pietro "Pete Catalina" Catalano, and Norman Wharton. During the 21 months he spent on death row, Arridy was liked and treated well by both the prisoners and guards alike.[1] Despite being on 23-hour lockdown in his cell, Arridy remained cheerful and was often seen laughing while making funny faces, using a metal food tray as a mirror.[22] Warden Roy Best became one of Arridy's supporters and joined the effort to save his life; he was said to have "cared for Arridy like a son", regularly bringing him gifts, such as toys, picture books, crayons, and handicraft material.[1][34] Best also would regularly bring homemade candy and cigars from home to share with Arridy.[57][61]

On December 15, 1937, an anonymous reader of The Evening Star sent the newspaper a wrist watch to be given to Arridy. The reader wrote that he was "impressed" by an article on Arridy's upcoming execution, at the time set for December 25 of the same year, which mentioned that when Arridy was informed of the date, "his befuddled mind grasped only the reference to Christmas, and he smiled", asking for a watch as a present.[62]

On November 4, 1938, as part of a nationwide petition put forth by attorneys Emmett Thurman and William O. Perry, a request was made for one or both of Arridy's eyes to be removed before execution for organ donation.[63] They represented fellow lawyer and Republican Colorado State Legislature candidate William Lewis, who was left blind following an accident when a tear gas grenade exploded in his hand, and hoped that Lewis could receive a second cornea transplant in this manner; a post-mortem extraction was considered infeasible due to concerns over damage to the lens by the cyanide gas used in the execution chamber. The unusual donor pool was chosen because Lewis "was reluctant to deprive a living person of his eye". Attorney General Byron G. Rogers said that voluntary cornea donation of a death row prisoner would be within Colorado law, citing the example of John Deering in Utah a month earlier, but Arridy denied the request, his reasoning being quoted as "You are not going to kill me and I need my eye". The three other death row inmates at Colorado State Penitentiary were asked following this, but also declined. Thurman and Perry, however, appealed to Rogers to have Arridy convinced to the cornea donation, as he was, at the time, scheduled to be executed the earliest of the inmates, the date having been set for November 20.[64][65][e] The warden made the second rejection in Arridy's name, as he stated that Arridy would be unable to give consent on account of his mental deficits.[67][68] Arridy also did not acknowledge the execution, replying "No, I am not going to die" when asked four separate times on the matter.[69]

On December 25, 1938, Arridy received a battery-powered toy train by Warden Best as a Christmas present.[70] Arridy quickly became particularly fond of the toy and he would often roll it between the metal bars to other cells for fellow inmates to catch and push back. In an exclusive press interview that same month, Arridy was asked if he wanted to be released, to which he said "No, I want to live with Warden Best" and "I want to get a life sentence and stay here with Warden Best. At the home the kids used to beat me… I never get in trouble here".[2] The warden said that Arridy was "the happiest prisoner on death row".[58] Before Arridy's execution, he said, "He probably didn't even know he was about to die, all he did was happily sit and play with a toy train I had given him."[1] At Arridy's request, Best gave meal privileges that allowed him to have ice cream for breakfast, lunch, and dinner on the day of his execution.[71]

When questioned about his impending execution on January 2, 1939, Arridy showed "blank bewilderment".[58] He did not understand the meaning of the gas chamber, telling the warden "No, no, Joe won't die".[72][73] Arridy did not understand the concept of death despite repeated attempts at explanation through Best and prison chaplain Albert Schaller in the prior year. Schaller stated that he believed the psychiatrists' assessment on Arridy's mental age and thus treated him as "below the age of reason", defined by Catholic canon law as age seven or younger.[57][72]

On January 5, Best convinced Arridy to agree to leave the train to a fellow death row inmate, Angelo Agnes, who would be executed in a double execution the same year in September.[74][75][76] Arridy was initially reluctant to give his favorite toy away, but warmed up to the idea after playing with Agnes and Norman Wharton for a few hours.[71][77][78]

Execution

editOn the morning of January 6, 1939, just a few hours before his execution that same evening, Arridy received an unscheduled final visitation from his family, consisting of his mother and sister, as well as an aunt and a cousin, which had been arranged as a surprise by Warden Best. Arridy had been unable to attend the funeral of his father Henry, who had died of pneumonia on 24 February 1937 at the age of 51,[79] and had not seen his mother Mary since his incarceration. It was noted that Arridy displayed a flat affect throughout the entire 15-minute visit; when his mother burst into tears upon seeing her son and hugged him while shouting "Joe, my Joe!", Arridy did not reciprocate, only saying "Hello" while looking off to the side.[80][f] Barring this, Arridy stayed silent for the duration of the visit and remained expressionless, except for a "slight smile" when fellow inmates brought in a three-gallon bucket of ice cream for the family to eat.[82][83][84][85]

When the death warrant was read to Arridy by Best and was asked if he understood, Arridy responded in a neutral tone, "They are killing me".[1] Before he left his prison block, Arridy went to each cell and shook the hand of every inmate to say goodbye. Norman Wharton reportedly told him, "Keep your chin up, Joe. We'll be with you soon".[22] For his last meal, Arridy requested a bowl of ice cream, which he reportedly had not finished before he would be taken to the chamber's holding cell, requesting for the remaining ice cream to be refrigerated so he could eat it later, not understanding that he was to be executed soon and would not return. Arridy became upset upon being told that he could not take his toy train and played with it one last time together with Angelo Agnes before the former had to leave, with Arridy saying "Give my train to Agnes" while he was led away.[86] Around approximately the same time, a Colorado Supreme Court meeting denied Arridy's attorney a stay of execution for another sanity hearing.[87]

Roy Best accompanied Arridy during the walk up Woodpecker Hill, where the gas chamber was located, and while passing the prison chicken coop, Best asked Arridy if he would "still raise the chickens in Heaven", as he had previously voiced a fondness for the hens. Arridy replied that he wanted to play the harp, which Best speculated was influenced by being told stories of angels in the afterlife by Father Schaller, specifically because he said that Arridy would be "swapping [his toy train] for a harp".[58][59][88][89] Arridy was reported to have smiled as he entered the gas chamber. After having his last rites and sitting down inside the chamber, Arridy's smile momentarily faded when he was blindfolded for the execution, but calmed down when the warden grabbed his hand and reassured him.[8][58][82][90] Members of the Drain family, who had previously attended Frank Aguilar's execution, did not witness the execution, despite Riley Drain stating after the execution of Frank Aguilar that he would be present at Arridy's execution as well.[91][1] Unlike Aguilar's execution, which was attended by 300 people, largely uninvited friends of the Riley family,[92] Arridy's execution was watched by just 50 people, who were all either official witnesses or staff.[93] Roy Best was noted to have been weeping during the execution, with him pleading with Teller Ammons, the Governor of Colorado, to commute Arridy's sentence, which Ammons refused to do. Ammons had previously declined to acknowledge a public petition with the same goal.[93] The gas was released at 8:13 p.m., with Arridy reportedly smiling as he lost consciousness after taking three breaths. He was declared dead at 8:19 p.m.[88][94][95] Arridy became the seventh prisoner in the United States to be executed via gas chamber.[96]

Aftermath

editSheriff Carroll

editPrior to his involvement in the Arridy arrest, George Carroll was regarded as "one of the best known peace officers in the mountain country" and heavily featured in the press throughout the 1930s. Carroll first became nationally known in 1928, when he joined the posse hunting the Barker Gang, participating in the killing of several of its members, including Kate Barker, motivated by the 1927 murder of one of his deputies, Arthur Osborn, by Herman Barker. In March 1933, Carroll was one of two officers credited with locating millionaire heir Claude K. "Charles" Boettcher II, son of Charles Boettcher, after he was kidnapped a month earlier in Denver.[97][98] Carroll's role in having Arridy convicted for the Drain murder only increased his fame. On November 15, 1939, Carroll was sentenced to six months jail and a $100 fine for assaulting a waitress: the judge suspended the sentence for "good behavior" while the fine was paid by Carroll's lawyer.[99] Carroll remained Sheriff of Laramie County until 1942[100] and died on May 18, 1961, aged 81.[101]

Other death row inmates

editTwo of Arridy's death row companions were executed later within the same year. On September 29, 32-year-old Angelo Agnes, convicted of the murder of his wife Malinda Plunkett Agnes and the attempted murder of his brother Roy Finley, and 41-year-old Pete Catalina, convicted of the murder of John Trujillo over a 50 cent poker debt, died in the gas chamber in a double execution. Just like with Arridy, Governor Ammons had again denied to give a last minute stay of execution. Agnes and Catalina held their breaths and remained alive for one minute after the gas was released; Catalina had agreed to let his heart beat recorded during the execution, showing that his heart rate remained at rest until he died.[74][75] The remaining death row inmate, Norman Wharton, convicted for the 1938 murder of security guard Arthur C. "Jack" Latting at The Broadmoor hotel during a botched robbery, received a pardon around 1948. Wharton had been aided in this pursuit by Warden Best and was granted clemency in part due to recommendations by prison staff, after he saved correctional officer Joe Gray from being beaten to death during the 1947 prison break.[102] Wharton was resentenced to life in prison and died at Colorado State Penitentiary on November 25, 1950, aged 40.[22][103][104]

Arridy family

editArridy's mother Mary moved to live with her brothers in Toledo, Ohio in 1947, adopting the surname "Areddy" after her brothers' spelling of the name, where she died at Cardinal Nursing Home on September 20, 1960, aged 75, and was buried at Calvary Cemetery.[105] His father Henry is buried in an unmarked grave in Pueblo's Roselawn Cemetery. His brother George was forcibly remanded to the State Home and Training School For Mental Defectives, the same institution Joe Arridy was held in, due to his own mental limitations. Despite numerous written pleas and a clean record with noted good behavior, George was never paroled due to concerns that his release might attract negative press attention, given the infamy of his brother. The 1940 census lists George as "single inmate" in the household of Myrtle E. Conner in Fruitvale, Colorado. He was last listed in the 1950 census, still in Mesa County, as "married patient" in the household of Emma Amy Ackerman. George's date and place of death are unknown.[9] His sister Amelia married U.S. Army soldier John E. Gannon in 1945, with whom she had two children; daughter Carolyn died in infancy. The couple moved to Memphis, Tennessee,[105] where Amelia died on May 25, 2012, aged 88, and was buried with her husband in Memphis National Cemetery.[106]

2011 posthumous pardon

editArridy's case is one of a number that received new attention in the face of research into ensuring just interrogations and confessions. In addition, the US Supreme Court ruled that capital punishment was unconstitutional for convicted people who are mentally disabled. A group of supporters formed the non-profit Friends of Joe Arridy and worked to bring new recognition to the injustice of his case, in addition to commissioning a tombstone for his grave in 2007.

Attorney David A. Martinez became involved and relied on Robert Perske's book about Arridy's case, as well as other materials compiled by the Friends, and his own research, to prepare a 400-page petition for pardon from Governor Bill Ritter, a former district attorney in Denver. Based on the evidence and other reviews, Ritter gave Arridy a full and unconditional pardon in 2011, saying "Pardoning Joe Arridy cannot undo this tragic event in Colorado history, it is in the interests of justice and simple decency, however, to restore his good name."[3][4][107]

Legacy

editIn June 2007, about 50 supporters of Arridy gathered for the dedication of a tombstone they had commissioned for his grave at Woodpecker Hill in Cañon City's Greenwood Cemetery near the state prison.[34]

Representation in other media

edit- The final interaction between Arridy and Best was the subject of a 1944 poem, "The Clinic", by writer Marguerite Young. The inspiration of the poem from the Arridy execution was only made public in 1966.[34][108]

- Robert Perske wrote Deadly Innocence? (1964/reprint 1995) about Arridy's case after conducting research on it and similar cases for years. He had tracked down the author of the 1944 poem before Young's death.[34] His book also explores other cases in which defendants were classified as disabled, and implications for police and the justice system.[21]

- In 2007–2008, producers Max and Micheline Keller, George Edde, and Yvonne Karouni, and Dan Leonetti, screenwriter, announced plans to make a film about Arridy and Gail Ireland, to be called The Woodpecker Waltz.[34] Leonetti won a New York screenwriting award for his screenplay, which attracted attention by producers.

- Terri Bradt wrote a biography of her grandfather, Gail Ireland: Colorado Citizen Lawyer (2011).[109] She was proud of his defense of Arridy, and began to work with the Friends of Joe Arridy on making his cause more widely known.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Pre-dating standardized spelling of the town name, Bqarqacha is spelled as Birosha in Henry Arridy's naturalization documents and in the obituaries of Henry and Mary Arridy as Barisha and Broocha respectively. Robert Perske writes the name as Berosha[6]

- ^ At the time, Syria did not describe a country, but was a broad term for the eponymous region that is now synonymous with the Levant. "Syrian" was thus often used as a generic term for not only Arabs, but all people from historically Muslim nations. Perske identifies Mount Lebanon as Arridy's ancestral home, which is located in modern-day Lebanon[7]

- ^ An example from the interrogation transcript: Questioner: When you got up from finishing assaulting the big girl [Dorothy Drain], what did Joe do? Aguilar: I got out on the side. Questioner: Then Joe assaulted the girl, didn't he? Aguilar: Yes.

- ^ Arridy was frequently misidentified as Mexican through initial reportings that described the attacker of the Drain girls as such,[9] with a report on Arridy's final visitation with relatives claiming that the family "conversed in Spanish" when they most likely spoke Arabic or Aramaic.[53]

- ^ By this point, William Lewis already had two volunteers to the donation, William Cardiff of Rawlins, Wyoming, and Ham Jenkins of Denver, Colorado. Lewis rejected their offers, however, as he only wanted "someone condemned to die", with Cardiff only being in temporary holding for a Cheque fraud charge and Jenkins being not incarcerated at all, as well as blind.[66]

- ^ Other sources reported that Arridy silently teared up while repeatedly uttering the word "mother".[81]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h "Begging Joe's pardon". 5280. October 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-02-07. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Warden, Rob. "Arridy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

With the mind of a six-year-old, Joe went to the gas chamber, smiling

- ^ a b c Coffman, Keith (2 January 2011). "Colorado governor pardons man executed for murder in 1939". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Disabled man executed in 1939 pardoned in Colorado". Miami Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Strescino, Peter (January 7, 2011). "Governor pardons Joe Arridy". Pueblo Chieftain. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Perske, Robert (September 1, 1995). Deadly Innocence?. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0687006151.

- ^ Perske, Robert (September 1, 1995). Deadly Innocence?. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0687006151.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Perske, Robert. "Chronology | Friends of Joe Arridy". Friends of Joe Arridy. Archived from the original on 2024-04-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Prendergast, Alan. "Joe Arridy was the happiest man on death row". Westword. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- ^ 1920 United States Federal Census for Henry Areddy

- ^ 1930 United States Federal Census for Henry T Arddy

- ^ 1940 United States Federal Census for Mary Arriag

- ^ "Barbara Drain Is Conscious And Rational". Greeley Daily Tribune. August 29, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Heel Prints Are Clue in Slaying". The Daily Times. August 17, 1936. p. 8.

- ^ "Hatchet-Killer Sought in Pueblo". The Evening Independent. August 17, 1936. p. 4.

- ^ "Arridy Not Slayer, Says State Prober". Greeley Daily Tribune. September 1, 1936. p. 2.

- ^ "Not Certain of Guild of Arridy Yet". Greeley Daily Tribune. September 2, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Escaped Inmate Shot And Killed - Police Believe That He May Have Murdered Girl". The Telegraph-Herald. August 18, 1936. p. 5.

- ^ "$1000 Reward Spurs Search For Slayer". The Pittsburgh Press. August 18, 1936. p. 2.

- ^ "Hunt Slayer Of Colorado Girl". Gazette and Bulletin. August 19, 1936. p. 6.

- ^ a b Robert Perske, Deadly Innocence? Archived 2021-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, Abingdon Press, paperback, 1995

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wells, Sandra K.; Alt, Betty L. (November 16, 2009). Mountain Murders: Homicide in the Rockies. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1608441365.

- ^ a b c Martin, Jack (October 27, 1936). "HOW THE POLICEMAN'S HUNCH SOLVED THE 'PERFECT CRIME' AT THE VICTIM'S FUNERAL". Times Daily. p. 4.

- ^ a b "Youth confesses attacking girls". Reading Eagle. August 27, 1936. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "'Just For Meanness' - Youth Admits He Killed 15-Year-Old Girl in Pueblo Home". The Telegraph-Herald. August 27, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Might Be Hatchet Slaying Solution". Lawrence Journal-World. August 27, 1936. p. 3.

- ^ "Admits Killing". The Spokesman-Review. August 28, 1936. p. 20.

- ^ "ARRIDY MAKES CONFESSION". The Pueblo Indicator. August 29, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Hallan Culpable De Homicido A Un Reo Mexicano". La Opinión (in Spanish). December 23, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Dos Sentenciados A Muerte De Colorado". La Opinión (in Spanish). April 19, 1937. p. 6.

- ^ "Aguilar Says He Murdered Drain Child". Greeley Daily Tribune. September 3, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Official Witness To Execution Drops Dead". The News-Sentinel. August 16, 1937. p. 4.

- ^ "YOUNG GIRL DIES AT FIEND'S HANDS". Spokane Chronicle. August 18, 1936. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i de Yoanna, Michael (June 6, 2007). "Sorry, Joe". Colorado Springs Independent. Archived from the original on 2024-03-31. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Frank Aguilar Identified in Second Slaying". Greeley Daily Tribune. October 8, 1936. p. 14. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c McShane, Terry (July 13, 1941). "The Murder of Dorothy Drain". St. Petersburg Times. p. 33.

- ^ "Slayer Finds Himself In New Tangle". The Spokesman-Review. October 7, 1936. p. 25.

- ^ "Precautions Taken To Prevent Lynching Of Feeble-Minded Youth Who Admits Murder In Pueblo". Greeley Daily Tribune. August 27, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Arridy Taken to Canon City". Greeley Daily Tribune. August 28, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Killers Taken To Penitentiary". The Telegraph-Herald. August 30, 1936. p. 2.

- ^ "THEY PLEADED NOT GUILTY". The Pueblo Indicator. October 10, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ "Jury Says Aguilar Must Die". Fort Collins Coloradoan. December 23, 1936. p. 1.

- ^ a b Radelet, Michael (January 15, 2017). The History of the Death Penalty in Colorado. p. 127. ISBN 978-1607325123.

- ^ "Drain Murderer is Executed: Official Witness Dies Almost Simultaneously". The News Journal. August 14, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ "Frank Aguilar Enters Lethal Chamber On Friday 13th". The World-Independent. August 10, 1937. p. 8.

- ^ "Colorado Slayer Breaks Down". Casper Star-Tribune. August 13, 1937. p. 1.

- ^ "Child's Death Held Accident". Associated Press. February 7, 1938.

- ^ "Police Believe Aguilar's Daughter Was Murdered". United Press. February 5, 1938.

- ^ "Child Perished In Burning House". The Pueblo Indicator. February 12, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ "JOE ARRIDY SAID SANE". The Pueblo Indicator. February 13, 1937. p. 1.

- ^ "Arridy Case Goes to Court". The Daily Sentinel. April 17, 1937. p. 4.

- ^ "JOE ARRIDY IS FOUND GUILTY". The Pueblo Indicator. April 24, 1937. p. 2.

- ^ "Arridy Eats Ice Cream on Eve of His Execution". The Daily Sentinel. January 6, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ "Executions in the U.S. 1608-2002" (PDF). ESPY.

- ^ "Executions in Colorado - 1859-1967". DeathPenaltyUSA.

- ^ Varnell, Jeanne (October 1, 1999). Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Big Earth Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 978-1555662141.

- ^ a b c "Here's more about Arridy..." The Daily Sentinel. January 6, 1939. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e "'Happiest Man' in death cell dies in chair". St. Petersburg Times. Jan 7, 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ a b "'I Want to Play' Smiles Imbecile Slayer of Girl as Gas Snuffs Out Life". Oakland Tribune. January 7, 1939.

- ^ "ARRIDY NEXT TO DIE IN CHAMBER". The Pueblo Indicator. September 3, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ Harmon, Tracy (February 27, 2014). "75-year-old case still compelling today". Pueblo Chieftain. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ "Doomed Man Gets Wish". The Evening Star. December 16, 1937. p. 2.

- ^ "Convict Asked To Give Eye To Blind Attorney". The Evening Independent. November 4, 1938. p. 24.

- ^ "Doomed Man's Eyes Asked". The Southeast Missourian. November 5, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ "Blind Lawyer's Friends To Plead For Slayer's Eyes". The Deseret News. November 8, 1938. p. 6.

- ^ "Blind Lawyer's Friends To Plead For Slayer's Eyes". The Deseret News. November 8, 1938. p. 6.

- ^ "Doomed Eye: Can Imbecile Give It Away?". Illustrated Daily News. November 6, 1938. p. 3.

- ^ "Condemned Men Cling To Hope - Refuse to Give Blind Man Eye Although Doomed". The Telegraph-Herald. November 11, 1938. p. 12.

- ^ "2 Condemned To Die To Give Eye, 2 Refuse". Greeley Daily Tribune. November 10, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ Moore, James (2018). Murder by Numbers – Fascinating Figures Behind The World's Worst Crimes. History Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0750981453.

- ^ a b "Friend In Condemned Row Given Electric Train". The Pittsburgh Press. January 7, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Condemned Prisoner to give train to another slayer". Reading Eagle. Jan 5, 1939. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "SEX SLAYER WILL LEAVE TOY TO HIS NEIGHBOUR". The Meriden Daily Journal. January 2, 1939. p. 9.

- ^ a b "Convict Meets Death By Gas Without Fear". The Deseret News. September 30, 1939. p. 8.

- ^ a b "Two Slayers Slated To Pay Debt Tonight". The Telegraph-Herald. September 29, 1939. p. 8.

- ^ "Cardiogram Shows Slayer Died of Gas Without Fear". Reading Eagle. October 1, 1939. p. 14.

- ^ "Toy Train Left to Death Row Pal If Promise Kept". The San Diego Union. January 6, 1939. p. 3.

- ^ "Slayer Wills Train To Pal". Prescott Evening Courier. January 5, 1939. p. 5.

- ^ "Short Local Items". The Pueblo Indicator. March 6, 1937. p. 1.

- ^ "Arridy Unmoved by Mother's Farewell". The Daily Sentinel. January 8, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ "Arridy Eats Ice Cream on Eve of His Execution". The Daily Sentinel. January 6, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Joe Arridy: Chapter Two – The Innocent". lebaneseglobalcentury.com. Archived from the original on 2024-06-19. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Weak-Minded Sex Slayer Puts Aside Toy Train to Die". The Courier-Journal. January 7, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ "Arridy Eats Ice Cream on Eve of His Execution". The Daily Sentinel. January 6, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ "Weak-Minded Joe Killed By Gas In Colorado Prison". Herald-Journal. January 7, 1939. p. 8.

- ^ "Man with Mental Age Of Six Executed in Colorado". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 7, 1939. p. 9.

- ^ "Joe Arridy Executed For Girl Murder". Lodi News-Sentinel. January 7, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Arridy Dies at Prison". The Daily Sentinel. January 7, 1939.

- ^ "22-year-old Idiot Happy As He Dies For Slaying". Middlesboro Daily News. January 7, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ Andersen, Dianna. "Joe Arridy". Canon City Public Library. Archived from the original on 2011-03-13. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Daughter's Death Is Half Avenged". Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 14, 1937. p. 10.

- ^ "Smallest Audience to Be at Execution of Arridy". The Daily Sentinel. November 16, 1937. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Young Killer Happy As He Starts On Journey To City With Pearly Gates And Streets All Paved With Gold". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. January 8, 1939. p. 2.

- ^ "Young Killer Grins In Death Chamber". Reading Eagle. January 7, 1939. p. 2.

- ^ "Cyanide Pellets Used In Colorado Death Chamber". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. January 7, 1939. p. 2.

- ^ "Arridy Gives Toy Train to His Fellow Convict". The Evening Independent. January 7, 1939. p. 1.

- ^ Breuer, William B. (January 30, 1995). J. Edgar Hoover and His G-Men. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0275949907.

- ^ "Denver Heir Gave Police Information That Led Them To Hide-Out In South Dakota Hills". Lawrence Journal-World. March 7, 1933. p. 1.

- ^ "SHERIFF FINED ON ASSAULT COUNT". Spokane Daily Chronicle. November 16, 1939. p. 47.

- ^ "George J. Carroll". Laramie County Wyoming.

- ^ "George J. Carroll (1923-1927)" (PDF). Wyoming Peace Officers Association.

- ^ "Saves Guard". Kentucky New Era. April 15, 1948. p. 6.

- ^ "Prison Hounds Aid Search For Slayer". The Pueblo Indicator. July 16, 1938. p. 1.

- ^ "May Be Linked In Frome Case". Prescott Evening Courier. July 1, 1938. p. 2.

- ^ a b "OBITUARIES - MRS. MARY AREDDY". Toledo Blade. September 21, 1960. p. 46.

- ^ "Gannon, Amelia Rose (1924-2012) in US, Veterans Gravesites". Forces War Records.

- ^ Kuroski, John (2018-07-26). "He Had An IQ Of 46 And Was Executed After Police Coerced A Confession For A Murder He Didn't Commit". All That's Interesting. Archived from the original on 2021-07-30. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ "The Poem | Friends of Joe Arridy". Archived from the original on 2024-05-19. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ Terri Bradt,'75; Gail Ireland: Colorado Citizen Lawyer Archived 2019-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, Bulletin, December 2012, Colorado College