The Jim Crow goldfield was part of the Goldfields region of Victoria, Australia, where gold was mined from the mid- to the late-nineteenth century.

Location

editThe goldfield extended between the localities of Daylesford and Hepburn Springs in the south, and Strangways at its confluence with the Loddon River in the north,[1] concentrated mainly around Yandoit.

Mentions of diggings named 'Jim Crow' appear in the press from 1851, but are vague and reported to be near Clunes.[2] The first Governor of Victoria, Charles Hotham, visited the diggings in September 1854 and it was reported in the Mount Alexander Mail that;

"On arriving at Tarrangower his Excellency and lady put themselves in communication with Commissioner Lowther, visited and inspected the Camp and various offices. After that they went out alone upon the diggings [ . . . ] At Tarrangower it transpired that the McLachlan diggings, between McLachlan's station and the aboriginal station of Mr. Parker, on the lower portion of the Jim Crow Creek, were supposed to be of a highly auriferous character, though making no pretensions to first-class diggings. Several hundred people had been prospecting there, and nuggets had been found an ounce in weight, but nothing further bad been reported with reference to the result of the prospecting. These diggings are about sixteen miles from Castlemaine. The name of the station on the map is Yandit [Yandoit]."[3]

Naming

editThe goldfield was named for the creek along which the mines were sited; "Jim Crow Creek," now renamed Larni Barramal Yaluk, which winds 26 km due north from Breakneck Gorge in Hepburn Regional Park, joining the Loddon River below the Guildford Plateau at Strangways.

Recent, more enlightened attitudes to First Peoples moved Mount Alexander Shire Council in conjunction with Hepburn Shire Council,[4] North Central Catchment Management Authority and DJAARA (formerly the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation) in 2021 to rename Jim Crow Creek, first applied to the area of Lalgambook/Mt Franklin by Captain John Hepburn who lived there in the 1830’s.[5] Both Hepburn Shire Council and Mount Alexander Shire Councils voted unanimously in April 2022 to name it, in local Dja Dja Wurrung language, "Larni Barramal Yaluk" (Home of the Emu Creek), acknowledging that the term ‘Jim Crow’ is knowingly derogatory as it stems from international racial segregation and anti-black racism, which was prevalent also in colonial Australia.[6][7][8]

Mining activity

editNearly 2,000 miners, many of whom had left the Maryborough diggings, were reported to be on the site in October 1854, though many had little success,[9] and shortage of water for panning and cradling was a problem.[10] Nevertheless a miner who had been on the diggings for two years reported in December 1854 that;

"...many bullock drays arrived during the week, all full of new arrivals, eagerly making for Jim Crow. Some new gullies have been opened, and every appearance of turning out well. The new rush is being worked to great advantage, and likely to continue for some time. Some parties are making three ounces to the tub; four lucky men made, on Wednesday, an ounce and a quarter to the bucket; in short, the whole are making what is commonly called good wages, and most of the old diggers must understand what that means. I have [never seen] a single instance of a digger leaving the Jim Crow being what is termed 'hard up,' but scores of instances I could mention of parties leaving for other diggings, who after a month or two, returned to the old favorite spot, with their pecuniary department embarrassed, highly satisfied with good wages, hitherto a certainty, on the Jim Crow."[11]

Legacy

editThe environmental devastation caused by gold mining was widespread and permanent in the district, decimating and displacing the Dja Dja Wurrung,[12] whose water sources included the Creek and associated underground springs. Mining destroyed the infrastructure they created over generations to maximise seasonal drainage patterns; channels and weirs they built out of timber stakes, to slow receding summer flows, were wrecked; water holes where the people gathered in smaller groups during periods of scarce rainfall and from which they transported water in skin bags when moving, were muddied, polluted and drained; the soaks they had dug between banks into sandy sediment to tap into the water table were likewise obliterated. Some of their waterholes in rock platforms of the Creek that they found or enlarged, then covered with slabs to protect them from animals, may still remain, unidentified.[13][12][14]

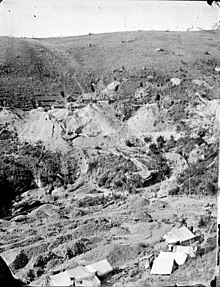

Mining activity along Larni Barramal Yaluk (Jim Crow Creek) was photographed in 1857/8 on wetplate collodion by Richard Daintree and Antoine Fauchery for their Sun Pictures of Victoria,[15] a copy of which is preserved in the State Library of Victoria.,[16] and traces in the landscape and relics of gold mining activity can still be seen there.[17][18]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Diggings". Geelong Advertiser. 1 November 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Tour Of Sir Charles And Lady Hotham On The Gold Fields". Mount Alexander Mail. 9 September 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Proposed Renaming Jim Crow Creek". Participate Hepburn. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ Council, corporateName=Mount Alexander Shire. "Mount Alexander Shire Council - Public notice - Proposed renaming of Jim Crow Creek". Mount Alexander Shire Council. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Elg, Hayley (5 October 2021). "Community push to get rid of racist creek name". The Macleay Argus. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Jim Crow Creek to be renamed in Aboriginal language". NITV. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Council recommends that Jim Crow Creek be renamed Larni Barramal Yaluk". www.hepburn.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Simson's (Maryborough) Diggings Gold Circular". Mount Alexander Mail. 6 October 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Simson's (Maryborough) Diggings' Gold Circular". Mount Alexander Mail. 13 October 1854. p. 5. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Jim Crow Ranges". Mount Alexander Mail. 1 December 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Susan; Davies, Peter (2019). Sludge : disaster on Victoria's goldfield (1st ed.). Carlton, Victoria: La Trobe University Press in conjunction with Black Inc. ISBN 9781760641108. OCLC 1101283189.

- ^ Chen, Lovell (2013). Thematic environmental history : final report June 2013. Lovell Chen. OCLC 1228917606.

- ^ Morrison, Edgar (1981). The Loddon Aborigines : tales of old Jim Crow. OCLC 271522680.

- ^ Fauchery, Antoine; Daintree, Richard (1858). Sun pictures of Victoria (1st ed.). Victoria. OCLC 977259296.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Daintree, Richard (1858). "Great Eastern Tunnel, 1500 feet long, Jim Crow diggings, Daylesford". State Library of Victoria. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Image - Swiss Tunnel at Jim-Crow Diggings - Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia".

- ^ "Jim Crow Creek Gold Mining Diversion Sluice (Heritage Listed Location) : On My Doorstep". Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2012.