Jezreel's Tower (also known as Jezreel's Temple) was built in Gillingham, Kent, England, by a religious sect founded by James Jershom Jezreel in the 1880s. It was demolished in 1961.

James Jershom Jezreel

editJames Roland White, later known as James Jershom Jezreel, was born about 1851. It is not known where but he declared on a marriage certificate in 1881 that he was a merchant's cleric, son of a warehouse superintendent and a bachelor.

On 27 July 1875, White enlisted in the British army and a few days later joined the 16th Regiment of Foot, based in Chatham, Kent. Soon afterwards, he became interested in the teachings of Joanna Southcott (1750–1814).

Southcott's followers claimed she was a prophet and her sealed writings purported to reveal answers to world problems. Her ultimate prediction was the imminent coming of a second Christ (Shiloh) of whom she, aged 65, was to be the mother. She died, childless, in 1814, leaving a sealed wooden box of prophecies, known as Joanna Southcott's Box, with the instruction that it be opened only at a time of national crisis, and then only in the presence of all 24 bishops of the Church of England.

The sect, however, continued and was expanded upon by other "prophets", including Richard Brothers, George Turner, William Shaw and John Wroe. Brothers and Turner were committed to asylums but Wroe attracted a strong following in Ashton-under-Lyne (now in Greater Manchester). Groups of supporters appeared in the south, including Chatham.

On 15 October, White joined a small branch of a Southcottian sect of Christian Israelites at Chatham, led by a Mr and Mrs Head and calling itself the New House of Israel.[1] Shortly afterwards he wrote a version of the manuscript to become known as the "Flying Roll" and took over the church. White adopted the name of James Jershom Jezreel and persuaded worshippers that he was the Messenger of the Lord.

The new headquarters

editWhite completed his military service in 1881 and set about building a headquarters for his church. The site — at the top of Chatham Hill and the highest point in the area — was chosen, Jezreel said, after a revelation from God.

He envisaged a building based on Revelation xxi, 16: "And the city lieth foursquare, and the length thereof is as great as the breadth ... the length and the breadth and the height thereof are equal."

It was intended to be a sanctuary, assembly hall and headquarters of the New and Latter House of Israel, as the church was now called. Around the perimeter there would be shops plus accommodation for Israel's International College — a school he had already set up at his home in Woodlands Road, Gillingham.

A community of his followers, known as Jezreelites, had already grown in Chatham, with many around Luton High Street. Many of the Jezreelites were tradespeople and, having given their money to the cause, had to make a living: the shops around the new HQ were for that purpose. The community ran a German bakery, a tea merchant's, a greengrocer's, a carpenter's, a dairy, a jeweller's, a cobbler's, a printing firm and a smithy.

Jezreel insisted his followers were abstainers from drink, a rule that did not apply to the leader, who often appeared to be drunk.

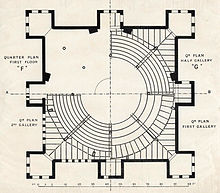

Jezreel wanted the new HQ to be a perfect cube, each side 144 ft long. The architects, however, persuaded him the design was impractical and he agreed to modified version — 124 ft on each side and 120 ft high at each corner. It was to be built of steel and concrete with yellow brick walls and eight castellated towers. The trumpet and flying roll, crossed swords of the spirit and the Prince of Wales feathers (signifying the Trinity), were to be engraved on the outer walls.

First, an enormous cellar had to be constructed for storage, lift machinery, a heating system — and the all-important printing presses to turn out thousands of copies of the Flying Roll and other literature essential to the sect. The circular assembly room was a vast amphitheatre, said to be capable of accommodating up to 5,000 people. In the roof would be a glass dome, 94 ft in diameter.

A circular platform in the centre of the assembly room floor was designed to rise under hydraulic pressure to a height of 30 ft. On it, the choir and preachers would rotate slowly.

The dome, supported by 12 steel ribs, would rise 100 ft above the floor, and be illuminated by an electric lantern 45 ft in diameter, the only source of light, for the room had no windows. The building was constructed of non-combustible materials intended to protect the Jezreelites when the Last Trump was called and fire rained down upon the rest of existence.

Outside, Jezreel planned gardens and stately avenues from adjoining streets, making it a focal point for the area. The estimate for these plans was £25,000 and completion was set for 1 January 1885.

Building the tower

editJezreel, by now a heavy drinker, fell ill towards the end of 1884 and died on 2 March 1885. Nobody mourned his death, for the word was without meaning in the sect, who expected his speedy resurrection. His coffin bore the simple inscription James Jershom Jezreel, aged 45 years, and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Grange Road cemetery near his home in Gillingham.

The sect was taken over by his wife Clarissa (née Rogers), a follower 10 years his junior whom he had married on 17 December 1881. (On the marriage certificate she added the name Esther by which she was then known.) She ensured the building work continued. The foundation stone was laid on 19 September 1885. The architects were Margetts of Chatham, and the builders were James Gouge Naylor of Rochester.[2]

Much of the tower's foundations were in place by early 1886 and some of the peripheral buildings were occupied. As building costs soared, Clarissa made economies in the budget for keeping followers. She found the cost of feeding Jezreelites was particularly high and declared the sect would become vegetarian, living off a diet of bread and potatoes.

"Queen Esther" (the derogatory name by which she was called in the press), however, was often to be seen in the area riding in a coach and pair and dressed in fashionable clothing. Inevitably, this led to dissent and the number of followers — at one point as high as 1,400 – began to dwindle. After a legal case involving one of the followers, who had given all his money to the cause, a mere 160 Jezreelites remained.

In July, 1888, Mrs Jezreel died suddenly from peritonitis. She was 28. The sect fragmented and work on the tower was suspended forever.

Downfall and decay

editThe tower and peripheral buildings were put up for sale in 1897 but the bidding failed to reach the asking price and it was six years before a buyer was found.

The flock of Jezreelites was by then barely 70 and some of the sect rented parts of the building. By 1905, the Jezreelites fell behind with their rent and the tower's owners repossessed the building. But then the contractors were bankrupt.[3] In 1911 a dance academy was operating in "Jezreel's Hall" and it was hired by Laura Ainsworth so that suffragettes could avoid the census.[4] The tower remained derelict until its complete demolition which took thirteen months between 1960 and 1961.[2][3][5]

Part of the site became an electro-plating works and was owned by Smiths Signs, until it was bought by L Robinson & Co (Gillingham) Ltd in 1967-68 as part of their group known for their product, Jubilee Clips. This became the home of L Robinson & Co. (Plating) Ltd, incorporated on 31 July 1968.

Throughout its existence, the tower or temple was a dramatic landmark. As well being the subject of numerous postcards, it was painted by Tristram Hillier in 1937 as part of a series of posters for Royal Dutch Shell. A copy is held in Tate Britain, London.[6]

The remaining buildings associated with Jezreel's Tower at the top of Canterbury Street, Gillingham, were demolished in late 2008.

Sources

edit- P.G. Rogers, The Sixth Trumpeter: The Story of Jezreel and His Tower

- E.J. Dark, "A Modern Tower of Babel: The Jezreel Temple, Chatham", The Strand Magazine 26 (1903), pp. 233-235

- R.A. Baldwin, The Jezreelites: The Rise and Fall of a Remarkable Prophetic Movement, Lambarde Press (1962)

- Stephen Rayner, "The Tower of Mystery Surrenders Its Secrets", Medway News May 2006

References

edit- ^ James Jershom Jezreel, Wikisource

- ^ a b Engineering and Technology 6 October 2009: Jezreel's tower - a huge structure that "could not be removed"

- ^ a b "Medway City Ark". Postcard of Darland Banks, Gillingham, Kent. c. 1905. Retrieved 12 March 2011. In the background behind the windmill, the partially dismantled Jezreels can be seen.

- ^ "Laura ainsworth".

- ^ "Medway City Ark". Postcard of Darland Banks, Gillingham, Kent. c. 1905. Retrieved 12 March 2011. In the background behind the windmill, the partially dismantled Jezreels can be seen.

- ^ The Tate