Jeffersonville is a city and the county seat of Clark County, Indiana, United States,[4] situated along the Ohio River. Locally, the city is often referred to by the abbreviated name Jeff. It lies directly across the Ohio River to the north of Louisville, Kentucky, along I-65. The population was 49,447 at the 2020 census.[5]

Jeffersonville, Indiana | |

|---|---|

| City of Jeffersonville | |

Skyline of Jeffersonville | |

| Nickname: Jeff | |

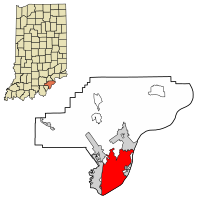

Location of Jeffersonville in Clark County, Indiana | |

| Coordinates: 38°20′15″N 85°42′09″W / 38.33750°N 85.70250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Clark |

| Established | 1801 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Moore (R)[citation needed] |

| Area | |

• Total | 34.35 sq mi (88.97 km2) |

| • Land | 34.08 sq mi (88.26 km2) |

| • Water | 0.28 sq mi (0.71 km2) |

| Elevation | 538 ft (164 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 49,447 |

| • Density | 1,451.04/sq mi (560.26/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 47130, 47131, and 47199 |

| Area code(s) | 812 & 930 |

| FIPS code | 18-38358[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2395463[2] |

| Website | cityofjeff |

Jeffersonville began its existence as a settlement around Fort Finney after 1786 and was named after Thomas Jefferson in 1801, the year he took office.

History

edit18th century

editPre-founding

editThe foundation for what would become Jeffersonville began in 1786 when Fort Finney was established near where the Kennedy Bridge is today. U.S. Army planners chose the location for its view of a nearby bend in the Ohio River, which offered a strategic advantage in the protection of settlers from Native Americans.[6] Overtime, a settlement grew. In 1791 the fort was renamed to Fort Steuben in honor of Baron von Steuben. Then in 1793 the fort was abandoned.[7]

19th century

editEarly history

editPrecisely when the settlement became known as Jeffersonville is unclear, but it was probably around 1801, the year in which President Thomas Jefferson took office.[7] In 1802 local residents used a grid pattern designed by Thomas Jefferson for the formation of a city.[8] On September 13, 1803, a post office was established in the city. In 1808 Indiana's second federal land sale office was established in Jeffersonville, which initiated a growth in settling in Indiana that was further spurred by the end of the War of 1812.[citation needed]

In 1802, Jeffersonville replaced Springville as the county seat of Clark County. Charlestown was named the county seat in 1812 but it returned to Jeffersonville in 1878, where it remains.[7]

In 1813 and 1814 Jeffersonville was briefly the de facto capital of the Indiana Territory, as then-governor Thomas Posey disliked then-capital Corydon and decided to live in Jeffersonville to be closer to his personal physician in Louisville. The territorial legislature remained in Corydon and communicated with Posey by messenger.[9]

Shipbuilding

editIn 1819 the first shipbuilding took place in Jeffersonville, and steamboats would become key to Jeffersonville's economy.[7] In 1834, James Howard built his first steamboat, named the Hyperion, in Jeffersonville.[7] He established his ship building company in Jeffersonville that year but moved his business to Madison, Indiana in 1836 and remained there until 1844. Howard returned his business to the Jeffersonville area to its final location in Port Fulton in 1849. There is an annual festival held in September called Steamboat Days that celebrates Jeffersonville's heritage.[10]

Underground Railroad

editAs a free state bordering the south, Indiana served as a crucial step along the Underground Railroad. By 1830, Jeffersonville was the first and largest route for fugitives crossing the Ohio River at Louisville. Hundreds of freedom seekers made their way north to Canada through Clark County.[11] There were many instances where Jeffersonville citizens helped fugitives flee enslavement. In the 1850s, Mayors Oswald Wooley and Uriah Damron were arrested for "running off" enslaved people. In 1863, Hannah Tolliver, a black wash woman, was arrested on the Louisville, Kentucky wharf as she attempted to help another woman cross the Ohio River to freedom. Hannah was convicted and became one of seven women inmates at the Kentucky State Prison at Frankfort. Dr. Nathaniel Field moved from Middletown, Kentucky to Jeffersonville in 1829. He was the head of UGRR activity in Jeffersonville, hiding escapees in his cellar during the day and sending them on to the next "station" at night. Field was President of the Indiana Antislavery Society and friend of Levi Coffin, the head of the Underground Railroad at Cincinnati and at Richmond, Indiana.[citation needed]

The Rev. Calvin Fairbank was arrested in Jeffersonville for helping the woman, Tamar, escape. He was tried in Louisville and convicted and spent decades in the Frankfort prison.[citation needed]

Civil War

editCamp Joe Holt

editDuring the Civil War Jeffersonville was one of the principal gateways to the South. This was largely due to its location directly opposite Louisville. Three railroads (including the Jeffersonville Railroad and the Ohio and Mississippi Railway) served Jeffersonville from the north, as well as the waterway of the Ohio River. Operating in the South, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad furnished the connecting link between Louisville and the rest of the South. These factors made the city a good location to house supplies and troops for the Union Army.[12]

In 1862, two area regiments established the first military camp in the city. The location was christened Camp Joe Holt, and the name was retained when the camp was converted to a hospital called Joe Holt Hospital.[13]

Evacuation to Jeffersonville

editIn September and October 1862, two Confederate armies led by Generals Braxton Bragg and E. Kirby Smith closed in on Louisville, a key strategic prize. General William "Bull" Nelson ordered women and children to evacuate. So many fled across the river to Jeffersonville that the city's hotels and rooming houses were filled to capacity. On September 24, General Don Carlos Buell and his men managed to reach Louisville barely ahead of the Confederates. The force of 100,000 Union soldiers successfully defended Louisville and forestalled any invasion.[6]

Jefferson General Hospital

editBetween 1864 and 1866 Port Fulton (now within Jeffersonville) was home to Jefferson General Hospital, the third largest hospital in the country at that time. The institution was built to replace Joe Holt Hospital and occupied land obtained from U.S. Senator Jesse D. Bright, a Confederate sympathizer. The land stretched down to the Ohio River, facilitating patient transfer from riverboats to the hospital. The facility contained 24 wards each radiating out like spokes on a wheel and all connected by a corridor one-half mile in circumference. Each ward was 150 feet long and 22 feet wide and could accommodate 60 patients. Female nurses and matrons were quartered separately from the men. During its nearly three-year existence the institution cared for more than 16,000 patients and served more than 2,500,000 meals.[14]

Construction of the Quartermaster Depot

editThe Jeffersonville Quartermaster Depot had its first beginnings in the early days of the Civil War as a storage depot for the Union Quartermaster Department. As the war came to a close all military supply depots along the Ohio Valley were shut down (except Jeffersonville's), and their supplies were stored at the Jeffersonville location.[15] In 1871, the U.S. Army began consolidating operations in the city into four square blocks.[6] Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Quartermaster Depot continued supplying troops engaged in frontier wars with Native Americans.[15]

20th and 21st century

editConstruction of the Carnegie Library

editOn December 17, 1900, Jeffersonville officially opened a new Jeffersonville Township Public Library in a room above the Citizens National Bank. 1400 books formed the initial collection. Soon, the Carnegie Foundation donated $16,000 for the construction of a new library building – a beaux arts, copper-domed landmark. The building was designed by Jeffersonville architect Arthur Loomis. Masonic officials laid the building's cornerstone on September 19, 1903, in Warder Park.[6] When the Carnegie Library opened in 1905, it contained 3,869 volumes. Whereas in later years grants from the Carnegie Foundation were scaled back to prevent the construction of lavish libraries, the library in Warder Park was relatively ornate.[16]

Due to the Ohio River Flood of 1937, the library suffered a near total loss of its collection. However, it reopened in November 1937 thanks to months of work and donations of money and books.[6]

World War I

editDuring World War I, Jeffersonville contributed to the war effort largely through its production capabilities. On the eve of war, the Quartermaster Depot began producing a wide range in items, including saddles, harnesses, stoves, and kitchen utensils. Most famously, though, the depot produced 700,000 shirts per month, earning it the nickname "America's largest shirt factory."[6] Meanwhile, the American Car and Foundry Company's local plant manufactured a variety of products ranging from components for over 228,000 artillery shells to 18,156 cake turners.[6]

Shortly after the war ended in 1918, civilian employment at the Quartermaster Depot fell to 445, and military presence dropped to just ten officers and two enlisted.[6]

Religious revivals in the 1920s

editFor a brief period in the mid-1920s and early 1930s, Roy E. Davis, a founding member of the 1915 Ku Klux Klan, hosted a series of religious revivals in Jeffersonville.[17] He also moved his First Pentecostal Baptist Church there, and held revivals in neighboring states. Meanwhile, he routinely challenged the Jeffersonville Evening News for its depiction of his church, eventually starting a new publication called The Banner of Truth to publicize his services and aid recruitment.[18] Much of his popularity stemmed from his vocal opposition of prohibition.[19]

In 1934, a fire destroyed Davis's First Pentecostal Baptist Church. After years of legal trouble, Davis was denied a permit to rebuild. He left Jeffersonville, and William Branham – formerly a ministering elder in Davis's church – became pastor of the congregation. Branham moved the group to a new building, eventually naming it Branham Tabernacle, as it is known today.[citation needed]

Flood of 1937

editJeffersonville was one of many communities affected by the Ohio River flood of 1937. After record rainfall in mid-January, 90% of the city was flooded, electricity was lost, all roads leading into the city were covered, and a levee failed. The Indiana National Guard deployed to the area to help those displaced, distribute much-needed emergency supplies, inoculate residents for typhoid fever, and purify drinking water. Finally by the end of the month the water began to recede. The flood left an estimated $250 million worth of damage throughout the Ohio Valley.[20][21]

"Little Las Vegas"

editIn the 1930s and 1940s, gambling was instrumental in Jeffersonville's recovery from the Great Depression and the Flood of 1937. This earned the town the nickname "Little Las Vegas".[22] During this time, Jeffersonville attracted the likes of Clark Gable, John Dillinger, Al Capone, and others. After Clarence Amster, a New Albany resident was gunned down on July 2, 1937, public sentiment turned against gambling and the mobsters it brought. In 1938, James L. Bottorff was elected judge and announced that gambling would not be tolerated. The Club Greyhound, a major dog racing track known for fixing races, was raided and closed within a year, with others soon following.[23]

World War II

editHaving acquired the Howard Shipyards in 1925, the U.S. Navy awarded the Jeffersonville Boat & Machine Company (later known as Jeffboat) a contract to build boats during World War II. Jeffboat built landing vessels such as the LST, and swelled in number of employees from 200 to 13,000 people. After the war ended, the Navy sold the Howard Shipyard to Jeffboat.[24]

Also during World War II, the Quartermaster Depot, in conjunction with Fort Knox, Kentucky, housed German prisoners of war until 1945.[25][26]

End of segregation

editJeffersonville ended segregation in its public schools in 1952, two years before the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. Prior to this, Jeffersonville High School was reserved for white high school students. Meanwhile, black students in grades one through twelve were sent to Taylor High School.[27] While The New York Times held up Jeffersonville as a model for all "southern-minded" cities, integration came at a cost. Though black students were allowed to attend the newly integrated Jeffersonville High School, black instructors previously employed at Taylor High School were terminated.[28]

This section is missing information about 50 years of history and development. (October 2021) |

Annexation

editOn February 5, 2008, the city of Jeffersonville officially annexed four out of six planned annex zones.[29] The proposed annexation of the other two zones was postponed due to lawsuits. One of the two areas remaining to be annexed was Oak Park, Indiana an area of about 5,000 more citizens. The areas annexed added about 5,500 acres (22 km2) to the city and about 4,500 citizens, raising the population to an estimated 33,100. The total area planned to be annexed was 7,800 acres (32 km2). The areas received planning and zoning, building permits and drainage issues services immediately, with new in-city sewer rates. Other services were phased in, such as police and fire, and worked jointly with the pre-existing non-city services until they were available.[30]

The Clark County Courts dismissed the lawsuits against the city on February 25, 2008.[31] This dismissal brought the remaining Oak Park area into the city. The population of the city grew to nearly 50,000 citizens, making it the largest annexation in Jeffersonville's history.[citation needed]

Big Four Pedestrian Bridge and Big Four Station

editConceived in the 1990s and completed in 2014, the Big Four Bridge was converted to a pedestrian bridge in a joint effort between Kentucky and Indiana governments. An average of 1.5 million pedestrians and bicycles cross the roughly-1/2 mile bridge each year. 1/4 mile ramps complete the bridge on each end. The bridge is also decorated with a colorful LED lighting system that operates from twilight to 1 am. The lights can be customized by request.[32]

On the Jeffersonville side of the bridge the city constructed Big Four Station, a plaza and park. The park features green space, fountains, a farmers market on Saturdays, a restroom, a bike-sharing station, a pavilion, a playground, and easy access to downtown shops and restaurants.[33] Big Four Station is also the home of the annual Abbey Road on the River, the largest Beatles-inspired music festival in the world, as well as other annual celebrations.[34]

Geography

editAccording to the 2010 census, Jeffersonville has a total area of 34.354 square miles (88.98 km2), of which 34.06 square miles (88.21 km2) (or 99.14%) is land and 0.294 square miles (0.76 km2) (or 0.86%) is water.[35]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,122 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,020 | 89.4% | |

| 1870 | 7,254 | 80.4% | |

| 1880 | 9,357 | 29.0% | |

| 1890 | 10,666 | 14.0% | |

| 1900 | 10,774 | 1.0% | |

| 1910 | 10,412 | −3.4% | |

| 1920 | 10,098 | −3.0% | |

| 1930 | 11,946 | 18.3% | |

| 1940 | 11,493 | −3.8% | |

| 1950 | 14,685 | 27.8% | |

| 1960 | 19,522 | 32.9% | |

| 1970 | 20,008 | 2.5% | |

| 1980 | 21,220 | 6.1% | |

| 1990 | 21,841 | 2.9% | |

| 2000 | 27,362 | 25.3% | |

| 2010 | 44,953 | 64.3% | |

| 2020 | 49,447 | 10.0% | |

| Source: US Census Bureau | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census[36] of 2010, there were 44,953 people, 18,580 households, and 11,697 families living in the city. The population density was 1,319.8 inhabitants per square mile (509.6/km2). There were 19,991 housing units at an average density of 586.9 per square mile (226.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.4% White, 13.2% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 1.9% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 4.1% of the population.

There were 18,580 households, of which 31.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.1% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.0% were non-families. 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 2.95.

The median age in the city was 37.3 years. 23.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.2% were from 25 to 44; 27.5% were from 45 to 64; and 11.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[3] of 2000, there were 27,362 people, 11,643 households, and 7,241 families living in the city. The population density was 2,014.7 inhabitants per square mile (777.9/km2). There were 12,402 housing units at an average density of 913.2 per square mile (352.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 82.50% White, 13.68% African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.84% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 0.65% from other races, and 1.97% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 1.80% of the population.

There were 11,643 households, out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.3% were married couples living together, 14.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.8% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.90.

The age distribution was 23.6% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 31.2% from 25 to 44, 23.8% from 45 to 64, and 12.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,234, and the median income for a family was $45,264. Males had a median income of $32,491 versus $24,738 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,656. About 6.9% of families and 10.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.9% of those under age 18 and 7.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

editA plethora of businesses call Jeffersonville home, including both locally owned and operated companies, as well as national ones. As of 2020, some of the top employers in the city included: Greater Clark County Schools (1600), Clark Memorial Hospital (1500), Clark Memorial Hospital Foundation (1066), Heartland Payment Systems (850), and Republic Bank & Trust of Indiana (721).[37]

Food outlets

editJeffersonville has a variety of restaurants along the riverfront, downtown, and other areas such as the Quartermaster Depot. These include small bars, restaurants, and fast food chains.[38] Jeffersonville is also the birthplace of the pizza chain Papa John's Pizza.[39]

Kitchen Kompact

editKitchen Kompact manufactures cabinetry in a converted portion of the Quartermaster Depot. The 750,000 square foot facility employs nearly 300 workers with an average tenure of 15 years. They produce around 10,000 cabinets per shift.[40]

National Processing Center

editJeffersonville is home to the United States Bureau of the Census's National Processing Center – the bureau's primary center for collecting, capturing, and delivering data. The facility comprises approximately one million square feet, and processes millions of forms per year. It also employs 1200 to more than 6000 people, making it one of southern Indiana's largest employers.[41]

River Ridge Commerce Center

editThe River Ridge Commerce Center is an industrial zone located on the outskirts of Jeffersonville near Charlestown, Indiana. Built on land previously occupied by the Indiana Army Ammunition Plant, it now hosts a variety of industries. These include manufacturing, aerospace, automotive, food & beverage, life sciences, logistics, and more.[42]

Shipbuilding industry

editUntil 2018, Jeffersonville was the home of Jeffboat, the largest inland shipbuilder in the US. At its peak, the barge manufacturer employed over 13,000 employees. The company closed due to an overproduction of barges, marking the end of 200 years of shipbuilding in Jeffersonville.[24] In 2022, city officials announced intentions to redevelop the 80-acre property.[43]

Education

editJeffersonville public schools belong to the Greater Clark County school system.[44]

Public schools

edit- Franklin Square Elementary

- Thomas Jefferson Elementary

- Northaven Elementary

- Riverside Elementary

- Wilson Elementary

- Parkview Middle School

- River Valley Middle School

- Jeffersonville High School

Private schools

edit- Sacred Heart Catholic School[45]

Events

edit- Taste of Jeffersonville

- Abbey Road on the River, music festival

- The Great Steamboat Race

- Jammin in Jeff, Riverstage concert series[46]

- Southern Indiana Pride Parade & Festival[47]

- Spring Street Festival, local art show and celebration[47]

- Steamboat Days, local celebration[citation needed]

- Thunder Over Louisville, air show and fireworks display

Nearby points of interest

edit- Big Four Bridge

- Clark County Indiana Museum[48]

- Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area

- Howard Steamboat Museum

- Indiana Army Ammunition Plant

- Jeffboat

- Jeffersonville Township Public Library

- Jeffersonville Quartermaster Depot

- NoCo Arts and Cultural District[49]

- Schimpff's Confectionery

- Vintage Fire Museum[50]

- Warder Park

Notable people

edit- Ernie Andres, MLB baseball player, basketball player and coach

- William Branham, evangelist

- Nick Dinsmore, professional wrestler

- Amanda Ruter Dufour, poet

- Drew Ellis, MLB fielder

- Mike Flynn, basketball player

- Jonas Ingram, United States Navy admiral, Medal of Honor recipient and United States Atlantic Fleet commander

- Judy Lynn, country music singer

- Travis Meeks, musician

- Zach Payne, member of the Indiana House of Representatives

- Linda Ridgway, artist

- Duane Roland, guitarist, co-founder of Molly Hatchet

- Jermaine Ross, NFL wide receiver

- John Schnatter, entrepreneur, founder of Papa John's Pizza

- Shanda Sharer, crime victim

- Walt Terrell, MLB pitcher

- Jimmy Wacker, MLB pitcher

- Richard B. Wathen, politician

- June Weybright, composer

- Natalie West, actress

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Jeffersonville, Indiana

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Jeffersonville city, Indiana". census.gov. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nokes, Garry J. (2002). Images of America: Jeffersonville Indiana. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 0-7385-2041-1.

- ^ a b c d e "Official History of Jeffersonville". Cityofjeff.net. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Biographical and Historical Souvenir for the Counties of Clark, Crawford, Harrison, Floyd, Jefferson, Jennings, Scott, and Washington, Indiana. Chicago Printing Company. 1889. p. 29. ISBN 9781548571665.

- ^ Life of Walter Quintin Gresham, 1832–1895 Archived September 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine By Matilda Gresham (Rand, McNally & company 1919) page 23-23

- ^ "Welcome to jeffsteamboatdays.com". jeffsteamboatdays.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Clark County Indiana History". www.co.clark.in.us. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Our County Seat". www.co.clark.in.us. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Camp Joe Holt and Jefferson General Hospital Photographs, 1865, Collection Guide" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Jeffersonville Jefferson General Hospital Looking West". Indiana Memory. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Falls City Engineers, Chapter VII: Civil War Engineering and Navigation" (PDF). publications.usace.army.mil. p. 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ THOMAS, LARRY (October 26, 2006). "Jeffersonville celebrates rebirth of Carnegie Library". News and Tribune. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Davis Is Released In Police Court". The Courier Journal. March 22, 1930.

- ^ "Church Publicity Policy Explained". Jeffersonville Evening News. April 18, 1931.

- ^ Davis, Roy (February 5, 1930). "A Preacher On Prohibition". The Courier Journal.

- ^ Slavey, Ashley; Simms, Megan; Cunningham, Wes; Brumfield, Eric; Morrison, Katy. "Great Flood of 1937". Discover Indiana. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "The Great Flood of 1937". weather.gov. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ West, Gary (August 5, 2018). "Club Greyhound had many colorful characters, stories". Bowling Green Daily News. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ BOYLE, JOHN (September 15, 2019). "NOW AND THEN: Goons, gambling, Greyhounds in Little Las Vegas". News and Tribune. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b GRADY, DANIELLE (April 2, 2018). "Historian: End of Jeffboat is end of nearly 200-year-old era". News and Tribune. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Jeffersonville Quartermaster Intermediate Depot – History and Functions". Qmfound.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "The German Prisoner of war camp in Indiana". Archived from the original on May 25, 2011.

- ^ Reel, Greta (May 12, 2020). "The History and Legacy of Jeffersonville's Taylor High School". JHS Hyphen Newspaper. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Stepro, Diane. "Taylor High School – Segregated Education in Jeffersonville, 1872–1954". Discover Indiana. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Jeff absorbs 4 annexed areas(by Harold J. Adams) Courier Journal February 8, 2008

- ^ Parts of Jeffersonville annexation official Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (by David Mann) The Evening News February 8, 2008

- ^ Jeffersonville annexation challenge is rejected(Ben Zion Hershberg) Courier Journal February 26, 2008

- ^ "Big Four Bridge | Waterfront Park". May 25, 2008. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Big Four Bridge and Big Four Station – Jeffersonville Main Street, Inc". July 9, 2015. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "About". Abbey Road on the River: May 26–30, 2022. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Local Businesses – City of Jeffersonville". cityofjeff.net. October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Dining". City of Jeff. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Wolfson, Andrew. "The real Papa John: Pizza entrepreneur John Schnatter makes no apologies for wealth, success, Obamacare remarks | Math whiz mixed pizza passion, finance". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "About Us". Kitchen Kompact. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "National Processing Center". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "River Ridge Commerce Center | Industrial Park in Indiana". River Ridge. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Jeffersonville officials announce partnership to redevelop former Jeffboat shipyard". Louisville Public Media. September 14, 2022. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "GCCS | Our Schools". Greater Clark County Schools |. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "SCHOOL". Jeffersonville Catholic. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Jammin in Jeff". City Of Jeffersonville Parks Department. December 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "2023 Indiana Festival Guide". Festival Guides and Reviews. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Clark County Museum – Jeffersonville Main Street, Inc". September 29, 2021. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Arts and Cultural District – City of Jeffersonville". cityofjeff.net. October 20, 2020. Archived from the original on October 2, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Vintage Fire Museum – Jeffersonville Main Street, Inc". April 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.