Jean Balukas (born June 28, 1959) is an American pool player from Brooklyn, New York, and considered one of the greatest players of all time.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Described as a "trailblazer, a child prodigy, a loner who rebelled against dress codes for women—the pool equivalent of Billie Jean King",[3] she is a five-time Billiards Digest Player of the Year, was the youngest inductee into the BCA Hall of Fame and the second woman given the honor, and was ranked fifteenth on Billiard Digest Greatest Players of the [20th] Century.[3][7][8][9]

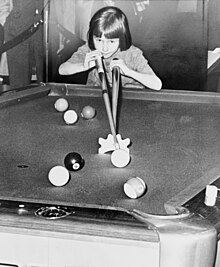

Jean Balukas performing in an exhibition in Grand Central Terminal in 1966 | |

| Born | 28 June 1959 Brooklyn New York U.S. |

|---|---|

| Sport country | |

| Professional | 1969 |

| Tournament wins | |

| Other titles | 100 |

| World Champion | Straight Pool (1977, 1978, 1980, 1982, 1983), Nine-Ball (1988) |

Balukas was considered a prodigy, coming to the public's attention first at 6 years of age at a pool exhibition held at New York City's Grand Central Terminal and thereafter appearing on television, including on CBS's primetime television show, I've Got a Secret. At just 9 years old she placed 5th in the 1969 U.S. Open straight pool championship, and placed 4th and 3rd respectively in the following two U.S. Opens. From that early start, Balukas completely dominated women's professional pool during the 1970s and 1980s.[7][10][11][12]

Balukas won five WPBA World Straight Pool Championship titles, the WPBA World 9-Ball Championship, eight BCA U.S. Open Straight Pool Championship titles and four WPBA U.S. Open 9-Ball Championship titles. Balukas has won over 100 professional tournaments, as well as a record streak of 16 first-place tournament finishes in a row, and was the only woman at the time to compete with men in professional play.[7][10][11][12] She quit the sport amidst controversy in 1988 while at the height of her ability, due to a dispute over her conduct in a match at the Brunswick WPBA World 9-Ball Championship of that year.[5][10]

Young prodigy

editJean's father, Albert Balukas, along with his partner, professional player Frank McGown, was the proprietor of a forty-eight-table pool hall called the Ovington Lounge in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, New York. Balukas's introduction to play was at 4 years of age, not on one of her father's tables but on a 4-1⁄2 by 9 foot pool table in the cellar of her childhood home, purchased by her parents to keep her four billiards-playing brothers out of local pool rooms.[13][14][15] In later years Balukas explained that she "almost never went to the pool hall and if I did go, I didn't play. I felt uncomfortable, and besides, girls didn't go in those days."[13]

Wielding an ivory-detailed cue made especially for her in 1965 by renowned cuemaker George Balabushka, at 5 and 6 years of age she would practice straight pool to 50 points after family dinners with her father's encouragement but not participation.[14][15] Many have assumed that she had been tutored in the game. However, Balukas states, "when they find out that my father doesn't play, many people think I must have learned the game from Frank McGown. That isn't true. I taught myself to play pool."[13]

In 1966, McGown staged a billiards exhibition at New York City's Grand Central Terminal. With her parents' permission, he brought along the 6-year-old Balukas, where she participated in the spectacle. The attention this generated, coupled with her prodigious talent, landed her a guest appearance in 1966 on WNEW-TV's Wonderama. Later that year, Balukas, along with her younger sister Laura, appeared on CBS's popular show I've Got a Secret. None of the panelists were successful in guessing that the 7- and 5-year-old sisters were pool enthusiasts.[14][15]

The following year Balukas appeared in an exhibition match at the bygone Carom Club, then located at 1697 Broadway in Manhattan. A second-grader at the time, according to her mother, Peggy, she did her homework and took a nap before appearing at the scheduled match.[14] In advertisements for the match, Balukas was billed as "the Little Princess of Pocket Billiards."[14] She was described by a reporter present as "a little girl with honey-blond hair...wearing a short yellow dress and green leotards...who resembles a young Shirley Temple."[14] To great applause she edged out her opponent, Roland DeMarco, a pool enthusiast and the President of Finch College. The final score was 50 to 42.[14]

In 1969, at 9 years of age, Balukas competed in her first BCA U.S. Open Straight Pool Championship, taking 5th place among a field of adults.[9][12] In the next two U.S. Opens, in 1970 and 1971, she placed 4th and 3rd, respectively. By that time she was already fairly well known, having had additional television appearances alongside such billiard stars and celebrities as Willie Mosconi, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Falk, Hugh Downs and Sonny Fox.[7][9][15] She would later appear on television many more times, in addition to broadcasts of pool matches, including an interview on The Mike Douglas Show airing on January 11, 1977, with Bernadette Peters and David Niven.[16]

U.S. Open Straight Pool Champion

editOn August 18, 1972, at 13 years of age Balukas won the women's division of the BCA U.S. Open Straight Pool Championship, along the way defeating five-time champion Dorothy Wise and taking home a prize of $1,500. Balukas was the U.S. Open's youngest winner ever and by a large margin. She roundly defeated her opponent in the finals, Madelyn Whitlow of Detroit, Michigan, with a score of 75–32 in 44 innings.[5][17][18] Reporting on the competition, The New York Times stated: "Miss Balukas showed signs of strong title contention throughout the tournament play as she defeated six opponents with precision shooting and near flawless strategy."[17]

In 1973, at 14, Balukas successfully defended her straight pool U.S. Open title, defeating runner-up Donna Ries, a psychologist from Kansas City, Missouri, with a final score of 75–72 in 42 innings and a high run of 26, earning her a $2,000 purse.[19][20] Earlier in the tournament she trounced Mieko Harada, a housewife from Kyoto, Japan, 75–1 in 20 innings and with a 25-ball high run. In the 1974 U.S. Open held at the Sheraton Hotel in Chicago, Balukas defended her title, again beating out Harada but by a much closer, nailbiting 100–99 final score. This was Balukas' third straight U.S. Open title at the age of 15. The close finale echoed the results seen in the men's division, where Joe Balsis defeated Jim Rempe 200-199 for the men's crown.[21][22][23][24]

In 1975 Balukas defeated Ries again in the U.S. Open semi-finals with a score of 75–15 in 15 innings,[23][25] dispatched Ames, Iowa native Gail Breedlove 75–19,[26] and then again faced and defeated Harada in the finals, claiming the $3,000 purse with a score of 100–63 in 39 innings and posting a high run of 23.[27] In 1976, then 17, Balukas took her fifth consecutive U.S. Open title, beating Gloria Walker of Cheyney, Pennsylvania 75–46 in 39 innings, winning a $1,700 purse.[28][29] Balukas went on to win the next two U.S. Open straight pool championships for a total of seven back-to-back wins, her streak foreclosed after 1978 by the discontinuance of the competition itself.[30][31]

Balukas was not just talented at pool but was an all-around good athlete. Starting at age 16, and for two other years, she was invited to participate in ABC-TV's Superstars. Held in Rotonda, Florida, the event pitted championship athletes from one sport competing in sports other than their own specialties, vying for cash prizes totaling $69,000. In her first appearance in 1976, while a junior in high school, she finished second taking titles in tennis and bowling where she won with 192 points. The winner that year was speed skater Anne Henning. Other competitors included, diver Micki King, tennis and golf pro Althea Gibson, Skier Kiki Cutter, sprinter Wyomia Tyus, and Tennis champ Martina Navratilova. The second place win was bittersweet for Balukas, because based on the award of prize money for placing at Superstars ($13,100), she lost amateur standing and was thereafter banned from competing in high school sports, also becoming no longer eligible for a college athletic scholarship.[13][32][33]

Balukas has won numerous other titles including five wins at the WPBA World Straight Pool Championship. Upon her first win in that tournament held at a convention hall in Asbury Park, New Jersey on August 14, 1977, she was described as "the 18-year-old prodigy from Brooklyn." There she again outplayed Walker (then of Ithaca, New York), with a score of 100–57, and earned a $1,001 prize.[34] Balukas has more U.S. Open wins than any other player, male or female, the runner up for the men being Steve Mizerak with four.[35] Her ball average over the seven U.S. Opens was in a different class than her opponents.[9] Balukas averaged 3.44 in 1972 with the next best, Gloria Walker, having an average of 2.37. In 1975 she averaged 4.05, while no other player averaged even 3.[9]

Playing with men

editAs early as the late 1960s, Balukas was performing exhibition matches with some of the top male players of the era, including Willie Mosconi and Irving Crane,[9] who were together considered between 1941 and 1956 the "best in the world, flat out".[9] In 1975, she again played the legendary Willie Mosconi on CBS' "Challenge of the Sexes" in both eight-ball and nine-ball competition. At 62 Mosconi was well past his prime, but a handicap was nevertheless given to the eagle-eyed youngster, allowing her all the breaks and the first shot regardless of whether she had made a ball or not on the break. Mosconi lost at both disciplines.[9][36] She later would play televised "Battle of the Sexes" matches with Rudolph Wanderone a/k/a Minnesota Fats in 1977, Ray Martin in 1979 and with Steve Mizerak in 1986.[37][38][39]

According to a 1987 interview with reporter Roger Starr of The New York Times, she learned much about pool through such activities but "she also learned that, even in fun, pool stars did not like losing in public, especially not to children, and less, even, to girl children. She also discovered that young men, including her brothers, shared the feeling of shame over losing to girls. She recalls, 'Whenever my brother Paul, the youngest of my four brothers, beat me at pool on the table downstairs at home, he would run through the house shouting 'I won, I beat her'. I guess that was one reason I worked all the harder at my game.'"[13]

On August 6, 1978, Balukas became the first woman to qualify to play in the men's division of the PPPA World Straight Pool Championship; a tournament with a 60-year history. This meant that she would be competing in both the women's and men's divisions of the tournament to be held on August 12 of that year at the Biltmore Hotel located at 43rd Street and Madison Avenue in New York City.[40]

Balukas played against the men in a number of competitions, including at least one televised match aired on March 25, 1979, between her and men's champion Ray Martin. The match was billed on the television schedule as part of a "Challenge of the Sexes," alongside similar male-female matchups between golfers Nancy Lopez and Andy North and coed participants in a skateboarding challenge match.[41] During 1980, Balukas again competed in the Men's division, in the PPPA World Straight Pool Championship hosted at New York City's Roosevelt Hotel. She was defeated in the second round at the hands of Steve Mizerak with a score of 150–93.[42] Her final standing in the tournament overall was 22nd, with 42 men trailing her in the rankings.[43] She also competed in the women's division of that tournament and was the victor, defeating Billie Billings, also of Brooklyn, with a score of 100–75. According to The New York Times, "Miss Balukas's triumph...was not only expected but routine. She was a defending champion and, in fact, has lost only two games to women in the past eight years."[44]

Balukas was initially entered in both the men's and women's divisions of the 1987 B.C. Classic, a nine-ball competition. After notable controversy (detailed below), she competed only on the men's side. Along the way she trounced Keith McCready 11–3 (at the time the 17th-ranked male player by money list, and who guest-starred as obnoxious hustler "Grady Seasons" in the 1986 film The Color of Money). Balukas finished in a tie for 9th place among many of the best players in the world.

Dress code controversy

editIn August 1987, at the annual B.C. Open hosted at a Holiday Inn in Binghamton, New York, Balukas was slated for competition in both divisions. After arriving, she discovered that for evening-scheduled matches she would be required to wear formal attire that she did not have with her. The men's division, by contrast, had no similar dress code. Balukas took a stand that the women should not be treated differently from the men, and accordingly refused to procure garments that would meet the unequal mandate.[13]

The women held a vote as to whether Balukas should be allowed to play. She later explained that "what hurt at Binghamton was that while I was trying to stand up for us being treated the same as men, the other girls held the tournament draw without me. By one vote, they kept me out. And some of the girls who are my best friends voted against me."[13] She did not agree at the time with the speculation of others that her professional rivals had their own self-interest at heart, knowing that with her out of the competition they would have a much better chance at the $5,000 first place prize award. Despite the women's snub and perceived chauvinistic terms, she nevertheless competed on the men's side, tying for ninth place.[13] Not long afterward, she indicated to a reporter that she was "thinking of dropping out of women's competition altogether."[13]

Soon after the dress code dust-up made headlines, a letter was sent to The New York Times by the Women's Professional Billiard Association (WPBA), by its president Belinda Bearden, disputing the facts as reported. According to the WPBA, the dress code was self-imposed by the players in an attempt to improve the image of women's pool and to attract more spectators and press to the sport, and that Balukas was the only participant at Binghamton unwilling to comply. They further explained that Balukas first withdrew from the women's division but later returned and asked to play after player assignments had been completed. A vote to allow her to play resulted in a tally of 8–7 in her favor, but after they moved to consult a player who was not present for the vote, Balukas again withdrew from the competition, and that was where the matter had ended.[45]

Break with the sport

editIn 1988, Balukas was playing against professional Robin Bell in a televised match of the WPBA World 9-Ball Championship held at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada. Bell, who was Balukas' best friend on the women's tour, had never beaten Balukas but had been playing very strongly in the tournament. With the score 2 games to 3 in favor of Bell in a race to nine games, Bell made the 9 ball on the snap two games in a row, making the score 5 to 2 in very short order.[5][10]

All television match players wore small microphones so that their words and the sounds of play could be heard by the audience. After Bell's second 9 ball break, Balukas reportedly muttered within the range of the microphone words to the effect that Bell was having a string of inordinately lucky shots. She was cautioned by the referee and play continued, with Balukas the ultimate victor with a final score of 9–5.[5][9][10] According to an interview with Balukas appearing in New York Woman magazine in 1991, Balukas's exact words were "Some world championship... beat me with skill, not luck."[5] Despite their off-the-table friendship, following the match Bell made a formal complaint to the WPBA about the incident. The WPBA's board of directors thereafter sanctioned Balukas $200 for unsportsmanlike conduct.[5][10]

Balukas was greatly incensed over the sanction and refused to pay on principle, turning away offers by others to pay the fine in her stead.[10] Balukas explains that "It wasn’t the $200... [Women] pool players, who were ranked three and six and five, were the ones who decided I should be fined. I felt it should have been done by an outside panel, not by my competitors."[5] The sides were at an impasse. Balukas refused to relent and the WPBA refused to lift the sanction and would not allow Balukas to play again until she paid the fine.[10] "Just because she was our premier player doesn't mean she was above the rules,"[10] said Vicki Paski in 1992, then president of the WPBA.[10] Professional Loree Jon Jones in the same interview expressed mixed sentiments: "Her not playing is, I guess, sad,"[10] but she reflected that in Balukas's absence, "we've all learned how to win."[10]

Balukas had also felt some heat from her solo venture into the men's arena. She had heard taunts from the men upon finding out she was going to play in their division, such as "I’m gonna put on a dress and go play with the women."[5] In early 1988, Balukas gave in to complaints from the men upon her entry to a Chicago-based tournament that it wasn't fair she should have the opportunity to play in both divisions when the men only had the opportunity to play in one, and withdrew from the men's side.[5] Balukas states that after she arrived in Chicago "I found out that the first- and second-place winners in the women’s event were going to be invited to play in the men’s event. I was stabbed in the back."[5]

There were other factors at play. Balukas admits to having been under great pressure, much of it self-imposed.[5] After she reached the pinnacle of her profession, "That’s when I started getting nervous... that’s when I started putting a lot of pressure on myself."[5] "Playing against the men, I learned to lose,... but [losing] hurt with the women because I was expected to win all the time."[5] Ultimately Balukas states that her break with the sport "...was a buildup of everything,... A little burnout, a little frustration. It just got to a point where I had so much animosity toward the pool world. And that was my out. You know, you're going to fine me? Well, see you later. That was my excuse to finally say I need a break."[5]

For Balukas's part, she returned to Bay Ridge, took over management of her family's pool hall, Hall of Fame Billiards on Ovington Avenue in Brooklyn,[10] and states that "I'm enjoying my life immensely... I have moved on."[10] In summing up these events in a 1992 article, The New York Times stated, "So America's greatest woman pool player competes only for the odd soda. If you're feeling lucky, drop by her poolroom ... If you're thirsty ... go elsewhere."[10]

Accolades

editIn 1975, when she was 15 years old, Balukas was already described as the "best female pool player in the world".[46] By 1987, Balukas's dominance of women's professional pool was so complete that it was described as "breathtaking" in its scope by The New York Times.[10] Announcers had long since stopped calling Balukas "the Little Princess," but presented her as "the Queen".[5][13] By that time she had won the BCA U.S. Open Straight Pool Championship eight of the prior nine years, and over the same time period, every single women's professional tournament in which she competed — 16 in all.[5][13] She had been honored as BCA Player of the Year five times.[7] In 1985 she became the second woman (after Dorothy Wise) to be inducted into the BCA Hall of Fame, with the additional honour of being its youngest inductee ever, at 25 years of age. In 1988, Balukas had already won over 100 professional tournaments in her career, before retiring at just under 30 years old.[7] In 1999, Balukas was ranked number fifteen on Billiard Digest's Fifty Greatest Players of the Century.[9]

Titles

edit

|

|

References

edit- ^ Steve Mizerak and Michael E. Panozzo (1990). Steve Mizerak's Complete Book of Pool. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-8092-4255-9.

- ^ Jordan Sprechman and Bill Shannon (1998). This Day in New York Sports. Champaign, Ill.: Sports Pub. Inc. p. 180. ISBN 0-585-04704-9.

- ^ a b c The New York Times Company (February 3, 1992). Clean Pool by Allessandra Stanley. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ Mariah Burton Nelson (1991). Are We Winning Yet?: How Women Are Changing Sports and Sports Are Changing Women. New York, NY: Random House. p. 18. ISBN 0-394-57576-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q New York Woman Magazine (1991). Too Good for Her Own Good Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine by Mary Bruno. September 1991 issue. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ Seyberts.com (date of copyright not provided). Interview with top male players on inclusion of women in the World 14.1 Championship. Retrieved May 8, 2007. Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Billiard Congress of America (1995-2005). BCA Hall of Fame Inductees: 1985 - 1991 Archived 2007-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ Sun-Times News Group (2006). NOTEWORTHY, Chicago Sun-Times, December 15, 1999, by Elliott Harris.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Billiards Digest (1999). "50 Greatest Players of the Century" by Kenneth Shouler. Billiards Digest Magazine. October 1999 issue, page 50-51 and 60.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p The New York Times Company (August 22, 1992). Billiard Master Reposes in Self-Exile by Douglas Martin. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Sun-Times News Group (February 15, 1988). Balukas Jumps Into the Shark Pool by Dave Manthey. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c Mike Shamos (1994). Pool: History, Strategies, and Legends. New York: Friedman/Fairfax. p. 33. ISBN 1-56799-061-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k The New York Times Company (October 18, 1987). The Best Woman in the Hall by Roger Starr. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g The New York Times Company (February 5, 1967). Girl Wonder of Billiards, 7, Took Cue Early by Dave Anderson. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c d The New York Times Company (August 5, 1973). For a Freckled Brooklyn Girl, Pool Is No Game; A Well-Kept Secret. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (January 11, 1977). Television. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ a b The New York Times Company (August 20, 1972). 8th-Grade Girl Captures U.S. Open Billiards Crown by Dave Anderson. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press (July 16, 1974). "Teenager Billiard Champion". The Morning Herald–The Evening Standard (Uniontown, Pa). p. 15.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 12, 1973). Miss Balukas, 14, Wins 2d Pocket Billiards Title. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ The Washington Post (then the Times Herald) (August 12, 1973). Balukas Holds Billiards Title. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ The National Billiard News (September 1979) page 24. "Pot Shots," by Bruce Venzke. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 12, 1974). Miss Balukas Wins 3d Billiards Title. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ a b The New York Times Company (August 11, 1975). West Takes U.S. Pocket Billiards Title . Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ United Press International (August 10, 1973). "Billiards Winner". New Castle News (New Castle, Pa).

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 6, 1975). Brooklyn Girl Gains in U.S. Billiards. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ Staff writers (August 7, 1975). "Sports Briefs: Billiards". Nevada State Journal. p. 15.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 10, 1975). Jean Balukas Wins 4th Title. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 16, 1976). Billiards to Jennings. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ^ Staff writers (August 16, 1976). "Sports Briefs: Teacher a Pool Shark". Nevada State Journal. p. 10.

- ^ The New York Times Company (December 18, 1977). Winners of Individual and Team Championships During 1977. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (December 17, 1978). Winners of Individual and Team Championships During 1978. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press (February 24, 1976). "Anne Henning, Jean Balukas Lead Women Superstars". Sheboygan Press. p. 17.

- ^ Associated Press (February 25, 1976). "Henning Wins Event, Takes Superstars Title". Sheboygan Press. p. 36.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 15, 1977). Hopkins, Miss Balukas Pocket Billiards Victors. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ Cohenn, Neil (1994). The Everything You Want to Know About Sport Encyclopedia. New York: Bantam Books. p. 80. ISBN 0-553-48166-5.

- ^ "Male Athletes Take Big Lead". Journal News, Hamilton, Ohio. Associated Press. November 11, 1975. p. 8.

- ^ "Television listings". The Daytown Sun. March 27, 1977. p. 4.

- ^ Stieg, Bill (AP) (August 16, 1986). "Woman Billiards Player Begins Career at Five; Now Aims at Title". The Gettysburg Sun.

- ^ "Television listings". The Valley indepedndent (Monessen, Pa). March 24, 1979. p. 10.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 6, 1978). This Week in Sports. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (March 25, 1979). Television This Week; of Special Interest. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 20, 1980). Jean Balukas Is Beaten In Billiards Tournament. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 16, 1981). Women Who Play Ponder Their Place in the Game by Fred Ferretti. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (August 24, 1980). Billiards Title to Varner In an Upset Over Sigel. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times Company (November 27, 1987). The Best Woman in the Hall. Retrieved March 25, 2008. Note: Identically titled but different article than previously referenced NYT article.

- ^ Russell, Dick (July 18, 1975). "She Wows 'Em In The Poolroom". Bridgeport Post. p. 15.

External links

edit- Jean Balukas's appearance on YouTube on CBS's I've Got a Secret in 1966 at age 6